Castrum

Castrum (Latin: Castrum, plural castra, diminutive castellum) was a common type of military camp used during ancient times, constructed by Roman legionaries. Castra referred to both temporary camps set up at the end of each day's march and long-term fortified fortresses located on the borders of the Empire. It was thanks to these powerful camps that the Roman Empire was able to expand its influence and maintain control even in the most remote regions far from the capital. Some of these castra eventually grew into entire cities, many of which have survived to this day. In this article, we will delve into the history and structure of this essential element of both the roman legions and the Roman Empire as a whole.

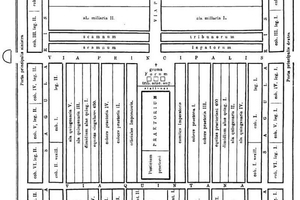

A fortified castrum's sketch

A fortified castrum's sketch

Historical Background

The universal method of organizing campgrounds likely emerged during the Punic Wars (3rd century BCE). Along the borders and state (consular or praetorian) roads, military camps were established at a day's march apart, resembling a city in their layout.

According to the Jewish historian and military commander Josephus Flavius (37-100 CE), in the 1st century BCE, legionaries would set up camp at the end of each day's march, allowing the duration of the campaign to be calculated in days based on the number of camps constructed. Until 69 CE, permanent border castra, similar to temporary camps, were constructed from earth and wood. It was only in 69 CE, with the rise of the Flavian dynasty, that the construction of long-term fortresses from brick or stone began.

By the 4th and 5th centuries CE, castra seemingly lost their significance, mostly due to a significant decline in the army's combat effectiveness and the abandonment of old military traditions. The Soviet historian V.D. Ivanov wrote on this subject: "The infantry of ancient Rome would not go to sleep until a trench was dug around the camp, until the earth mound was bristling with slingshots made of sharp stakes, until the fortified camp was secured by three gates. Then, having grown accustomed to playing the role of emperors, the soldiers' freedom exempted them from the heavy and monotonous daily labor... and soldiers could only be forced to dig trenches in the face of obvious danger..."

Setting up a camp

The construction of a temporary camp followed a specific procedure. Typically, towards the end of the legion's daily march, a small group was sent ahead to select the most suitable and defensible location. Strict requirements existed for the camp's placement: it had to be well-protected on all sides, convenient for defense, and ideally have a water source. After selecting the site, the first step was to mark the position of the commander's tent and the surrounding "praetorium" (Latin: praetorium) - a square or rectangular area where the tents of all senior officers were situated. From this point, the directions of the two main roads (cardo and decumanus) were established, intersecting the camp in a cross shape and marking the positions of all other parts of the camp.

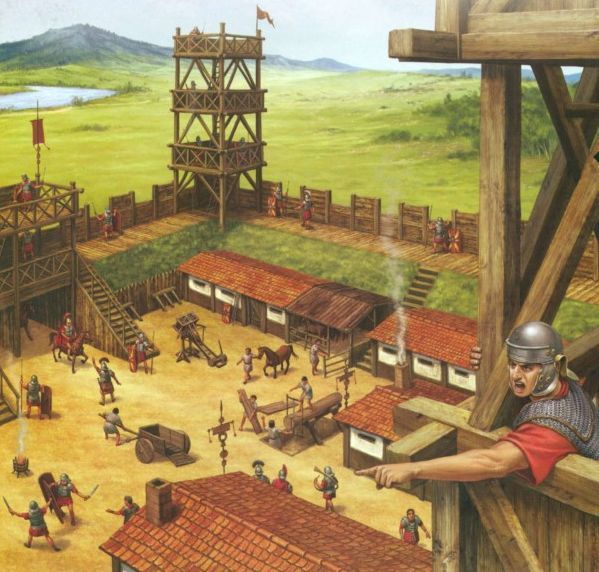

When the legion approached the designated site, the soldiers immediately began constructing fortifications. The work was often carried out fully equipped, in armor and armed. The first task was to construct the fortifications: a trench was dug along the entire perimeter of the camp, and a solid rampart was built, reinforced with earth or stones, or with wickerwork during long stays. The rampart was always reinforced with sharpened stakes. It is worth noting that the entire system of Roman fortifications followed the pattern of fossa - agger - vallum (ditch - rampart - wall), although there could be several ditches.

A reconstruction of Castrum's defens structures

A reconstruction of Castrum's defens structures

After the fortifications were built, the legionaries proceeded to set up the tents. Initially, the commander's and senior officers' tents were pitched, positioned around the praetorium. The soldiers' tents were set up last. It was mandatory to maintain a specific distance between the tents and the perimeter fortifications to facilitate movement within the camp and to prevent enemy arrows from reaching the tents from beyond the fortifications. Typically, depending on the terrain and tactical situation, it could take between 2 to 5 hours to complete the camp setup, after which the legionaries settled in for the night.

The ancient Greek historian Polybius (200-120 BCE) provides a generalized description of a marching castrum. He states that a Roman military camp was constructed in the shape of an "equilateral quadrilateral," or square, with the streets laid out in a manner resembling a city: "The tents are removed from the rampart on all sides by two hundred feet. The entire open space offers great and varied conveniences. It is quite convenient for entering and departing the camp because the individual units, each with their own street, lead to this open space, so the soldiers do not collide, push, or trample each other on a single road." It should be noted that the majority of the discovered remains of castra indicate that rectangular layouts were more prevalent in camp construction rather than equilateral squares. There also existed a theoretical recommendation regarding the ratio of the camp's sides, stating that the length and width should be in a 3:2 ratio. This guideline was mentioned in the treatise "On the Construction of Military Camps" (Latin: De munitionidus castrorum), attributed to a certain Pseudo-Hyginus (a pseudonym ascribed to several ancient authors, and the true identity of the author behind it is yet to be determined).

Different sources provide different sizes for the castrum. The average typical size of a camp was approximately 450-500 meters in width and 550-650 meters in length. The camp had gates on all four sides, connected by two main roads. Usually, if the camp was set up in close proximity to the enemy, one set of gates faced the enemy (these gates were called porta praetoria), while the opposite gates (porta decumana) sometimes accommodated traders who followed the legion. The gates were always made wide enough to allow for easy movement out of the camp. The center of the camp was the praetorium, which, as mentioned before, was where the commander's tent and the tents of the senior officers were located. Often, an altar for sacrifices was also placed in the praetorium. In addition, the praetorium housed a place for divination, the tent of the quaestor (treasurer), and a tribunal, a raised platform from which the commander could address the legionnaires. Auxiliary troops were positioned behind the praetorium, while the majority of the camp, on both sides of the main street "via praetoria," was occupied by the tents of the legionnaires and cavalry.

Camp removal

Dismantling the camp followed a specific procedure as well. At the first trumpet signal, the tents were taken down, and at the second signal, the tents and all other baggage were loaded onto pack animals. Josephus writes: "At this same time, they burn the ramparts so that the enemy cannot take advantage of them, confident that if needed, they can easily construct a new camp in that place. The third trumpet signal announces the departure - the ranks are formed, and any soldier who falls behind hastens to take his place in formation. Then the herald, standing to the right of the commander, asks in the native language three times: 'Is everything ready for battle?' The soldiers reply with the same number of shouts, loudly and joyfully: 'Yes, ready!' Often, anticipating the completion of the question, full of martial enthusiasm, they raise their hands in a salute and give a single war cry." "Then they set out on their march and proceed in silence, in orderly formation. Each one remains in line, as in battle."

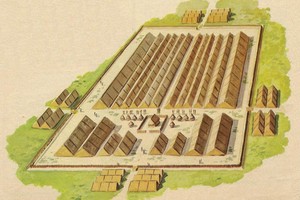

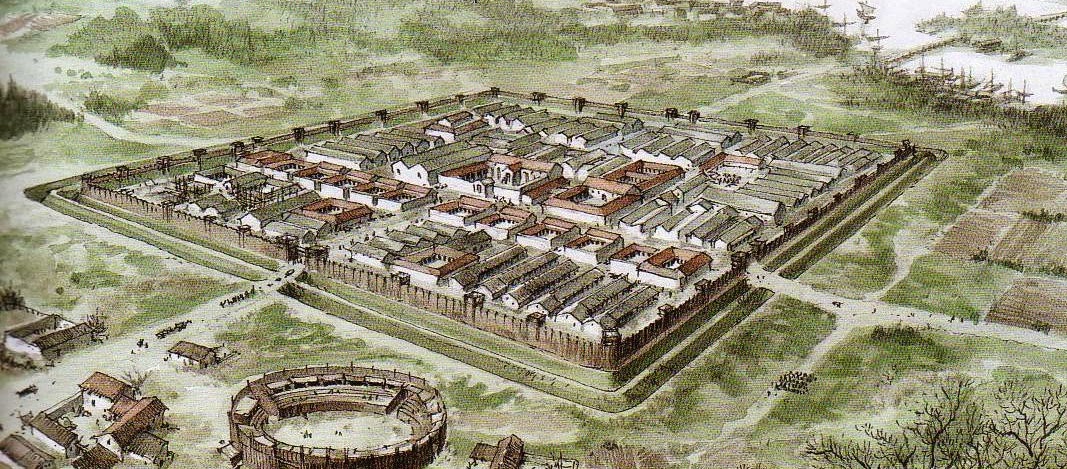

Castrums - Cities

In important strategic locations, long-term castrums were constructed. They were fortified with wooden or later stone walls and had stone barracks and buildings for the military administration and public institutions instead of tents. The layout of these castrums remained practically the same as temporary camps. The area inside the walls was called the "urbs," resembling a city, and the strip of land outside the walls was called the "pomerium." Legionnaires and their families usually settled in these castrums. Such a castrum included a principia (headquarters), praetorium, barracks, warehouses, training facilities, workshops, barracks for the soldiers of the first cohort, stables, and a hospital.

Over time, these camps, connected to the metropolis by roads, became centers of trade and craftsmanship. They developed residential areas with houses for the families of soldiers, artisans, and merchants. Similar settlements were created by Roman commanders at the end of the Republic and by emperors who disbanded their armies after wars. In reward for their service, soldiers (veterans and reservists) received money and land for settlement and would often settle in compact masses. Typically, the population of such a small town consisted of veterans from the same military unit. Among the cities that grew from Roman castrums are Turin, Florence, Lucca, Timgad, London, Vienna, Bonn, Trier, Algiers, Budapest, Belgrade, and others.

A sektch of a long-term castrum's structure

A sektch of a long-term castrum's structure

"Urbs Quadrata" or Square city

Wherever Roman legionnaires carried the imperial will, they always carried Rome with them: Roman civilization, Roman laws, Roman culture. Therefore, every camp-fort, especially a long-term one, built even in the most remote province, somehow contained a particle of distant Rome. This was facilitated, in particular, by the square shape of the camp.

Rome was often referred to as "Urbs Quadrata" (Latin for square city), implying a principle of the foundation of sacred monuments that became the basis of an equally sacred city, which is not easily understood by modern people. All the buildings that were constructed were part of the order, or the Whole (as Marcus Aurelius called the world order). In simple terms, buildings erected by humans in accordance with sacred rituals were on the level of those forms created by the divine principle. Thus, the circle symbolized the divine reality, while the square represented the earthly. Therefore, the sacred city of Rome was identified with not only the earthly but also the heavenly principle.

Castrums, which embodied the order that the Roman Empire brought to its provinces, also embodied both of these principles, proclaiming to the less educated conquered peoples the immensely great foundation on which Roman civilization was built.

Castrum in Weißenburg (Birciana)

One of the most well-known castrums, remnants of which have survived to this day. It is believed to have been built in 90 AD to defend the newly acquired territories north of the Danube by Emperor Domitian. Originally constructed of wood, it was rebuilt in stone in the middle of the 2nd century AD.

It is known that in the castrum of Weißenburg during the period of the 1st to 3rd century AD, the I Hispana Auriana Ala (Auxiliary unit of the Roman army) was stationed. Additionally, there are suggestions of temporary deployment of the IX Batavian Cohort (Cohors IX Batavorum) in this camp in the early 2nd century AD.

The ruins of the Weißenburg castrum are currently protected by the German government and are listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The camp was first discovered by German archaeologists in 1890, and excavation work was completed by 1905. Since then, gradual restoration work has been carried out on the baths.

At present, the castrum-museum, in addition to the remains of the large complex of baths and the foundation of the principia building, features reconstructed stone gates (porta decumana) that were fully recreated in 1990.

Castrum of the Tenth Legion near Masada

In 66 AD, during the Jewish revolt, the fortress of Masada was captured by the Zealots, Jewish rebels who advocated for the eradication of Hellenistic and Latin culture from Jewish lands and the overthrow of Roman rule. During the capture, according to the account of Josephus Flavius, the Zealots massacred the Roman garrison stationed in the fortress. In 67 AD, the Sicarii ("the daggermen," a combat group of the Zealots that used guerrilla tactics against the Romans) appeared in the fortress, and they were largely responsible for the beginning of the First Jewish-Roman War. After the capture of Jerusalem in 70 AD, the Roman army turned its attention to Masada, which remained as the last stronghold of the defiant radicals. The task of capturing the fortress was assigned to the Legio X Fretensis under the leadership of the Roman politician and general Lucius Flavius Silva. The defenders of the fortress numbered just under a thousand, but due to their tenacity and the advantageous natural location of the fortress, protected by sheer cliffs, the siege lasted for three years. The Tenth Legion constructed a siege ramp at the foot of the fortress, an embankment that allowed them to approach the fortress walls. This ramp has survived to this day and is used as a tourist route, along with the castrum whose ruins, after nearly two thousand years, still preserve the memory of the accomplishments of the Tenth Legion.

The siege ended tragically in 73 AD. Responding to the call of the leader of the Sicarii, Eleazar ben Ya'ir, the besieged people collectively took their own lives on the first day of the Jewish holiday of Passover. In describing these events, Josephus Flavius refers to the account of two women who, together with several children, took shelter in a cave and told the Romans who entered the fortress about how the men had killed their wives and children and then each other. "I know for certain that the Romans will be troubled to see that we have not been taken alive and that they have been deceived in their hopes of gaining spoils. Only the provisions will be left untouched to demonstrate after our death that we did not suffer from hunger or lack of water, but that we preferred death to slavery, just as we resolved in advance... ...Thus, they all perished, convinced that they left not a single soul for the Romans to triumph over. The Romans went up to Masada the next day, and when they found the heaps of dead bodies, they did not rejoice at the sight of their fallen enemies but stood in silence, struck by the greatness of their spirit and their unyielding contempt for death" - Josephus Flavius.

Related topics

Legion, Legionnaire, Ancient military campaigns, Roman Empire, Roman Republic

Literature

- Josephus. "The Jewish War" / translated by Ya. L. Chertka in 1900, with an introduction and translator's note. Vekhi Library, 2004.

- Livy Titus. Istoriya Rima ot osnovaniya goroda [History of Rome from the foundation of the city]. edited by M. L. Gasparov and G. S. Knabe, vol. I-III. Moscow, 2002

- Polybius. Universal History, vol. I (books I-V), Moscow, 1890.

- Polyakov Evgeny Nikolaevich, Mayorova E. V., Shapovalova E. E. Features of a regular planning grid in the military architecture of ancient Rome // Bulletin of TSASU. 2009.

- Maklyuk A.V. Army of the Roman Empire. Ocherki traditsii i mentalnosti [Essays on Traditions and Mentality], N. Novgorod, 2000

- Dion Cassius. Dio’s Roman History: In Nine Volumes / With an English Translation by E. Cary, on the Basis of the Version of H. B. Foster. London; New York, 1914-1927

Gallery

Gallery