Cera

Cera (from Latin "tabula cerata" - wax tablet) is a small board made of a hard material such as boxwood, beech, or bone, with a hollowed-out recess filled with dark wax.

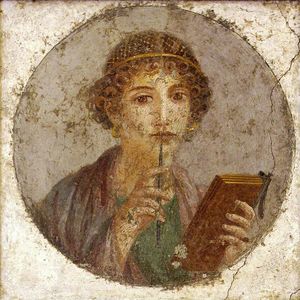

On the board, people would write by making marks in the wax with a pointed metal, wooden, or bone stylus (Greek: στῦλος, Latin: stilus). If necessary, the inscriptions could be erased or smoothed out, allowing the reuse of the tablet. Wax tablets were used for daily notes, reminders of tasks, debts, and obligations. They served as a draft for texts that were later transferred to papyrus or parchment. Sealed tablets were used for making wills, conveying secret orders by officials, various statements, receipts, and even reports. The oldest archaeological finding of a wax tablet dates back to the 7th century BCE (Etruria). In Europe, wax tablets were used as everyday items until the mid-19th century.

The ancient Greeks called a wax-covered tablet "delta" (Greek: δέλτος), probably because in ancient times they had a triangular or trapezoidal shape. The edges of the tablets were pierced, and strings, straps, or rings were threaded through the holes to connect two or more tablets together. Two connected tablets were called a diptych, three a triptych, and four or more a polyptych. Herodotus mentioned a diptych in his story of the cunning of the Spartan king Demaratus (VII, 239). To convey the plans of the Persian king Xerxes to his fellow citizens, Demaratus scraped off the wax from a diptych ("deltion diptychon"), wrote a letter on the surface of the wood itself, and then covered the entire writing with wax. Clean wax tablets did not raise suspicion since they were common items for a literate person.

In wealthy Roman houses, archives of wax tablets were kept in a special room called the "tablinum" (from Latin "tabula" - tablet). Pliny the Elder described such archives in his "Natural History" (XXXV, 7), but he used the term "codex" to refer to parchment books of the modern form, which later became the common term. Prominent and wealthy individuals preferred to use luxurious tablets, often made of ivory and sometimes adorned with gold, with elaborate designs on the outer side. It was a custom for Roman consuls to give such tablets as New Year's gifts to acquaintances and friends. Business people and politicians would sketch drafts of documents and letters on these tablets and then dictate them to professional scribes called "librarii". According to Cicero, Caesar had seven scribes with him (Pro Sulla, 14).

Many archaeological findings were made during excavations in the house of the financier Lucius Caecilius Iucundus in Pompeii on July 3-5, 1875. (Comparable in volume were the findings in Herculaneum, but the excavations there continued throughout the 1930s). Remains of a chest were discovered above the portico of Iucundus' house, containing 127 diptychs and triptychs. Despite being damaged by volcanic ash and partially charred, a significant portion of them was deciphered. The documents preserved on these tablets mostly date from 53-62 AD, with only two from earlier times, 15 and 27 AD. Pompeian triptychs consisted of tablets with recesses filled with wax and were intended for writing on the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th pages only. The main text of the document was written on the 2nd and 3rd pages, then the first and second tablets were fastened together (the second and third pages remained covered), and a string was threaded through a special groove in the smooth fourth page, secured with seals of witnesses who were present during the conclusion of the transaction. Each witness placed their signature next to their seal, inscribing it with ink on the wood. The main types of documents preserved in the house of Caecilius Iucundus were receipts, payment acknowledgments, and so on.

Tablets played a significant role in the creation of ancient books. Here, the initial author's concept took shape, and individual parts of the work were sketched out. Only after careful refinement were literary works transferred to papyrus or parchment. Sometimes the finishing of the work was not very meticulous, leading to inaccuracies and errors. This is the origin of the numerous inaccuracies in Pliny the Elder's "Natural History".

Literature

- Borukhovich V. G. In the world of ancient scrolls. - Saratov: Publishing House of the Saratov University, 1976. - 224 p.

- Dobiash-Rozhdestvenskaya O. A. Istoriya pis'ma v Sredniye veka: Rukovodstvo k izucheniyu latinskoy paleografii [History of Writing in the Middle Ages: A guide to the study of Latin Paleography].

- Zaliznyak A. A., Yanin V. L. Novgorod Psalter of the beginning of the XI century — the oldest book of Russia // Bulletin of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 2001, vol. 71, No. 3, pp. 202-209.

- Medyntseva A. A. O "doskakh" russkikh letopisei i yuridicheskikh aktov [About the "boards" of Russian chronicles and legal acts]. - 1985. - No. 4. - pp. 173-177.

- Rybina E. A. Obrazovanie v srednevekovom Novgorodom (po arkheologicheskim materialam) [Education in medieval Novgorod (based on archaeological materials)]. - Yekaterinburg: Bank of Cultural Information, 2000 — - (Problems of the history of Russia. Issue 3). pp. 25-44.