Mithridates Eupator

Mithridates Eupator

Mithridates VI Eupator, also nicknamed Dionysus (132-63 BC) – the king of Pontus in 117-63 BC, went down in history as a formidable and strong opponent of Rome, who almost managed during three wars to destroy the power of Rome in Asia Minor and the Black Sea region. However, in the end, he lost and, in order not to become a prisoner of the Romans, ordered his bodyguard to kill him with a sword.

He died in Panticapaeum (now the modern city of Kerch, Republic of Crimea, Russia), on the acropolis, which was located at that time on a mountain dominating the city. Over time, the mountain where Mithridates died was renamed in his honor to Mithridates.

Bust of Mithridates the Great, aka Mithridates VI Eupator. Located in the Louvre Museum, Paris. The bust was made in the Hellenistic period (4th-1st century BC).

Bust of Mithridates the Great, aka Mithridates VI Eupator. Located in the Louvre Museum, Paris. The bust was made in the Hellenistic period (4th-1st century BC).

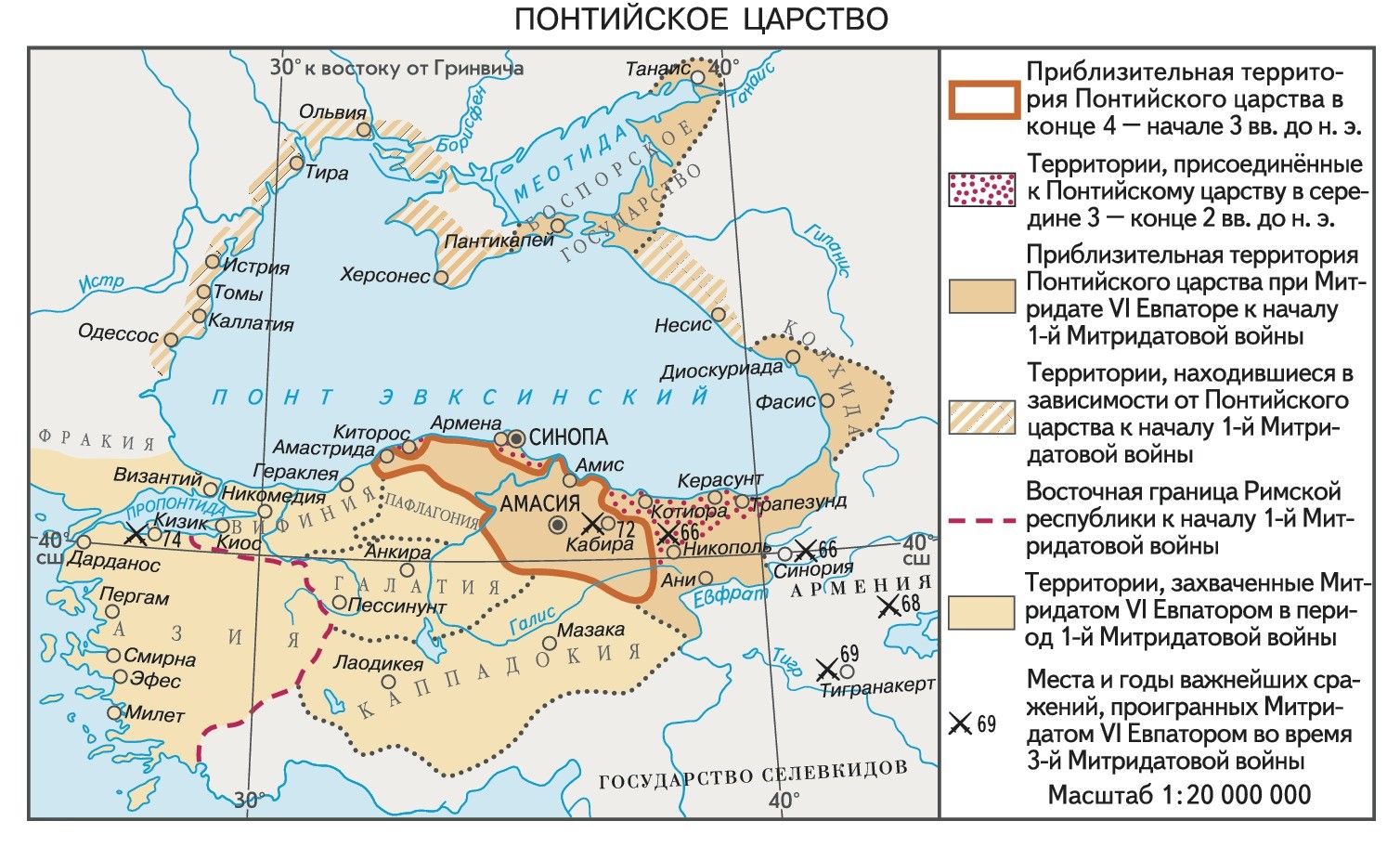

Pontic Kingdom

The Pontic Kingdom (Pontus) – a Hellenistic state in the central, northern, and north-eastern parts of the Asia Minor peninsula, located on the southern coast of Pontus Euxinus (the Black Sea). The Pontic Kingdom existed in the 4th - 1st centuries BC (302-63 BC).

The Pontic Kingdom bordered Bithynia (on the Black Sea coast) and Paphlagonia in the mainland's interior to the west, Phrygia (later and Galatia) to the southwest, Greater Cappadocia to the south, Lesser Armenia to the southeast, and Colchis to the east.

This state was inhabited by Greeks, Cappadocians, Paphlagonians, Phrygians, Armenians, and Iranians.

The state language in the country was Greek.

The country had many valuable minerals, especially metals, and livestock breeding was conducted in the Pontic mountains. Agriculture was developed in several regions, and the country's inhabitants were also engaged in trade.

Pontus was ruled by the kings of the Mithridatid dynasty. Pontus reached its zenith during the reign of Mithridates VI Eupator, after whose defeat Pontus began to gradually decline, severely curtailed in its territories in favor of neighboring Roman provinces.

After the death of Mithridates VI Eupator in Pontus, the western part of the Pontic Kingdom was detached by Rome for the newly created province of Bithynia and Pontus, while the new Polemonid dynasty started to rule in the east, under whom, severely curtailed in its territories, Pontus played the role of a buffer state between Rome and Parthia. In 63 AD, the Roman Emperor Nero (reigned 54-68 AD) incorporated the remaining Pontic territories into the Roman province of Galatia.

Map of the Kingdom of Pontus and its expansion

Map of the Kingdom of Pontus and its expansion

Short Biography of Mithridates VI Eupator

Mithridates was born in the city of Sinope (now the city of Sinop in Northern Turkey), which at the time belonged to the Pontic Kingdom.

Mithridates had two nicknames: Eupator and Dionysus.

The nickname Eupator meant "born of a noble father".

He received the nickname Dionysus in early childhood when lightning struck his cradle, igniting the swaddling clothes but not harming the baby. This reminded of the myth of the ancient Greek god Dionysus, and in memory of this incident, the ruler had a small scar on his forehead.

Mithridates VI's ancestors were representatives of the most noble Macedonian and Persian families. His father was the king of Pontus, Mithridates V Euergetes, who in turn was the heir of the king of Pontus, Pharnaces I, who through his parents had kinship with the Persian king Darius III. Mithridates VI's mother was Laodice VI, the daughter of the Seleucid ruler Antiochus IV, who had among his ancestors one of the generals and diadochi of Alexander the Great - Antiochus I Soter, the creator and first ruler of the Seleucid state.

He believed in Zoroastrianism, but sometimes, especially when it was beneficial to him, he worshipped Zeus – the Fighter or simply Zeus, the chief God of the Greek pantheon of gods.

In addition to Mithridates VI, Mithridates V and Laodice VI also had a younger son, Mithridates Chrestus.

Mithridates VI was raised with a combination of Greek and Persian educations. From the Greeks, he received manners, knowledge of Greek culture, literature, and religion, and from the Persians, he received military exercises and skills, which he combined with the Greek ones. He also learned horse riding and loved to hunt wild beasts.

Mithridates' contemporaries were struck by his tall stature and strength. He knew all the languages of his numerous kingdom and freely communicated with each of his subjects in their language – this was, incidentally, 22-25 languages. He was cruel and cunning, hypocritical, like any tyrant of the East in those years, but at the same time loved and contributed to the development of Greek art, literature, and philosophy.

His father died in 120 BC, and his sons were still minors, so their mother, Laodice VI, became the regent of the Pontic Kingdom, who favored Chrestus more out of the two brothers. As a result, fearing for his life, Mithridates VI fled, according to one version to the inaccessible mountains of Pontus, according to another to the king of Lesser Armenia - Antipater.

So he lived for 7 years as an exile (from 11 to 18 years old).

During his flight, Mithridates was forced to wander in the mountains of Pontus and beyond, and it was then that he learned to endure hardships and developed an antidote to many poisons in his body. Because he was afraid of being poisoned, he took a little poison of different kinds.

In 113 BC, Mithridates returned to Pontus and ascended his father's throne, becoming the king of Pontus, under the name Mithridates VI Eupator. He arrested his mother and younger brother. They soon died in prison, and were buried with royal honors by the order of Mithridates VI.

Mithridates VI had many concubines, and he himself was married 5 times and had a child from almost every wife, and even 5 children from the first wife, not counting the children born of his numerous concubines.

During his reign, Mithridates proceeded to expand the borders of his kingdom, in some places acting through diplomacy, in others through dynastic marriages, and in some places openly annexing (capturing) the territories of his neighbors.

Mithridates VI was able to annex Paphlagonia to the Pontic Kingdom in 107 BC; the Bosporan Kingdom in 108/107 BC; Colchis and part of western Armenia in 104/103 BC.

As a result, this led to a struggle with Rome. He fought 3 wars with Rome, but during the last, 3rd war, his favorite son Pharnaces betrayed him and he lost to the Romans, and in order not to become their captive, he ordered his bodyguard to kill him with a sword.

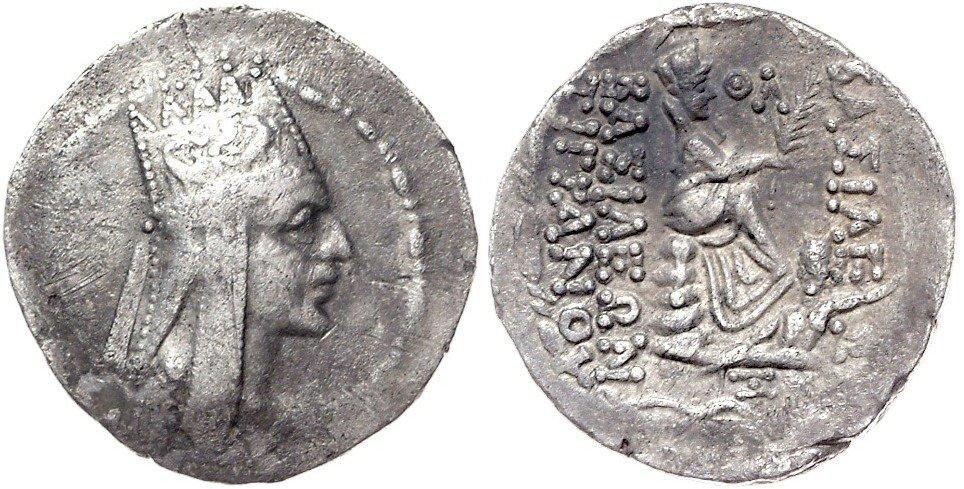

Pont. Mithridates VI. Tetradrachm G (87-86 BC). Weight-16.88 g; d – 33 mm. Callatay — D1/R1A. According to Hoover, the degree of rarity is R1. Private meeting.

Pont. Mithridates VI. Tetradrachm G (87-86 BC). Weight-16.88 g; d – 33 mm. Callatay — D1/R1A. According to Hoover, the degree of rarity is R1. Private meeting.

War with Rome

Causes of wars:

From the Roman Republic: territorial expansion of the borders of the Roman Republic in Asia Minor. Prevent the loss of territories in Greece and Asia Minor. Economic policy for trade and tax development.

From the Kingdom of Pontus: the expansion of the territory of the Kingdom of Pontus and the creation of a great power in the East, led by him as an absolute monarch. To achieve this goal, he had to

conquer both the local rulers and knock Rome out of the territories in the East where it managed to settle (the province of Asia). Because of this, Mithridates VI tried to unite all the anti-Roman forces in the Middle East and the Balkan Peninsula in order to dislodge Rome from Asia Minor and Greece.

Generals of Rome and Pontus who participated in the Mithridatic Wars:

Military leaders of Rome and allies of Rome: Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Lucius Licinius Lucullus, Gnaeus Pompey the Great; Ariobarzanes I Philoromanes king of Cappadocia in 95-63 / 62 BC, was also a relative of Mithridates VI – married to one of his daughters; Bruttius Sura; Lucius Licinius Murena; Aulus Gabinius; Flavius Hadrian; Gaius Valerius Triaria.

Military leaders and Pontic allies of Mithridates VI: Mithridates VI Eupator; Archelaus; Manian; Taxi; Arcavi (one of the sons of Mithridates, he died during the war); the tyrant of Athens Artinian (died after the capture of Athens troops L. K. sulla in 86 BC); the Governor of Bithynia Nycomed, who later defected to the Romans; the rulers of Cappadocia Ararat VI and VII Ararat; Corioli; Mahar (one of the sons of Mithridates, who would later rebel against father and die); Mithridates (one of the sons of Mithridates VI, ruler of Cappadocia, father executed for suspicion of treason); Quintus Sertorius, a partisan of g.Marius, who will rebel against the supporters of L. K. Sulla in Spain and negotiate cooperation with Mithridates VI and even send one of his assistants to Pontus to train Pontic troops in Roman technology and methods; Tigranes II, the Great ruler of Greater Armenia; Pharnaces (one of the sons of Mithridates, who at the end of the 3rd Mithridatic War rebelled against his father, he also inherited the remnants of the Pontic kingdom, after Mithridates ' death).

Similarly, Mithridates in his struggle with Rome, for money, was helped by Mediterranean pirates, primarily Cilician.

In addition, Mithridates himself had a strong navy and numerous land armies.

Antique coin of the first century BC depicting the King of Great Armenia Tigran II the Great. Private collection.

Antique coin of the first century BC depicting the King of Great Armenia Tigran II the Great. Private collection.

The First Mithridatic War (89-85 BC)

Informed about the situation in Rome - there was first the Social War, then the civil war between Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Sulla - Mithridates decided to take advantage of the situation and declare war on Rome.

Using as a pretext the attack by Rome's ally King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia on the border areas of the Pontic Kingdom, Mithridates declared war on Rome in 89 BC.

His allies in this war were the Mediterranean pirates, the population of the Balkan Peninsula discontent with Roman rule, and his son-in-law, King Tigranes II of Armenia.

As a result, Mithridates VI's army counted about 250,000 infantry, 40,000 cavalry, including 130 chariots, and about 400 warships.

At the beginning of the war, Mithridates was able to capture Bithynia, Phrygia, Paphlagonia, making them part of the Pontic Kingdom.

In order to gain the support of the local population and the nobility, he everywhere proclaimed the restoration of freedom and self-government in the cities, freed slaves, announced the abatement of arrears and exempted from taxes for five years.

He also managed to gain naval control of the entire Eastern Mediterranean with his fleet. He also managed to capture Asia Minor, except for its southwestern part and the island of Rhodes.

Afterwards, Mithridates began to entrust command to his generals.

Archelaus, his general, he sent at the head of the army to Greece. In Greece, Archelaus was able to capture the island of Delos, and in Laconia and Boeotia the locals joined him.

In Athens, with the help of Mithridates, his supporter Aristion came to power in 88 BC.

Finally, in Rome, Sulla managed to defeat Marius and headed an army of 30,000 to Greece to wage war against Mithridates and his generals.

Sulla landed in Epirus in the spring of 87 BC, replenished food supplies there, collected money and allies for war with Archelaus, and moved to Central Greece, the region of Attica. Here, except for Thebes, he was able to free all of Greece from the forces of Archelaus, who, together with Aristion, took refuge in Athens and its port city Piraeus. Pursuing them, Sulla divided his army, sending part to besiege Athens itself and the other part to besiege Piraeus, the "mouth of Athens."

During the siege of Athens and Piraeus, in need of money to pay his legionaries and wood to build siege engines and towers, Sulla committed sacrilege, robbing all the Greek temples near Athens, taking all their wealth and cutting down part of the sacred groves.

Piraeus and Athens held out all winter of 87/86 BC, but due to famine, Athens surrendered in March 86 BC. Sulla gave the city to his army for looting, and Aristion and his supporters were executed.

Piraeus soon fell, and just before its fall, Archelaus managed to escape to Thessaly.

In Thessaly, Archelaus was able to gather the remnants of his army and unite them with the reinforcements from Pontus brought to him by another Mithridates' general, Taxiles, increasing his forces to 120,000 men.

Sulla was in doubt whether to pursue Archelaus, who now had more troops than him, or to return to Rome, where a coup had taken place in favor of Gaius Marius, who had returned from exile, and instead of Sulla, Marius' supporter, consul in 86 BC Lucius Valerius Flaccus was sent with two legions.

However, even before Flaccus's arrival, Sulla decided to fight Archelaus and won. The battle took place at Chaeronea in 86 BC, a place where in 338 BC all of Greece, after a fierce battle, had also succumbed to Alexander the Great's father, Philip II of Macedon.

Learning of the defeat of the armies of Archelaus and Taxiles, Mithridates, gathering a new army under Dorilaus, sent it through Thrace to Macedonia to aid the defeated Archelaus and Taxiles. Dorilaus entered Boeotia, where he joined the remnants of the army of Archelaus and Taxiles. In Boeotia, near the village of Orchomenus, another battle took place in the fall of 86 BC between Mithridates' generals and Sulla. As a result, in a stubborn battle, Sulla again managed to defeat his Pontic opponents. Archelaus fled to Chalcis. Sulla, having plundered Boeotia, stayed to winter in Thessaly in 86/85 BC, where he began to build a fleet.

At this time, the army of Valerius Flaccus captured Byzantium and crossed over to Asia Minor, where it was openly supported by the nobility, discontented with Mithridates' policy, who, in addition, in order to maintain his power over Asia Minor, had switched from flattery to cruelty and executions.

However, due to poor discipline and lack of authority, Flaccus's soldiers soon mutinied and killed him. The new commander became one of Flaccus's legates, Gaius Flavius Fimbria.

Fimbria was able to restore order in the army and inflicted a number of defeats on Mithridates.

At the same time, in the spring of 85 BC, the fleet built by Sulla appeared in the Aegean Sea. It was commanded by Sulla's quaestor, Lucius Licinius Lucullus.

Mithridates found himself in a difficult position and decided to ask for peace without much thought. He decided to negotiate peace and conclude peace with Sulla.

In the end, Sulla, under other circumstances, would not have made peace with Mithridates, preferring to defeat him, but his opponents in Rome were increasingly taking away his power, so he agreed to make peace with Mithridates in order to move from the East to the West, to Italy, more quickly.

Sulla put forward the following conditions for making peace: Mithridates had to return all the conquests he had made in Asia Minor since the beginning of the war, pay a contribution of 3,000 talents (according to other data - 2,000), and give 80 warships.

Mithridates, not immediately, but under the threat of war continuation, agreed to all the terms of peace that Sulla presented to him.

As a result, peace was concluded in August 85 BC in the city of Dardanus on the Hellespont (the ancient name of the modern Dardanelles Strait connecting the Marmara and Aegean Seas), at a personal meeting of Sulla with Mithridates, who accepted all the Roman conditions.

At this time, Fimbria's army was stationed near Pergamum and was increasingly subject to discipline breakdown. When Sulla approached it, a large part of Fimbria's soldiers joined him, others fled, and Fimbria himself soon committed suicide.

After this, Sulla established order in Asia Minor. Rewarding the remaining loyal allies of Rome (the island of Rhodes, Lycia, Magnesia, and others), executing the supporters of Mithridates who fell into his hands, and imposing a large monetary contribution on the Roman province of Asia amounting to 20,000 talents.

In 84 BC, Sulla crossed from Asia Minor to Greece with his army, where he spent the winter and prepared to resume the war with Gaius Marius and his supporters in Italy.

In the spring of 83 BC, Sulla sailed from Greece to Italy, where the civil war between the Marianites and the Sullanites soon resumed.

Thus ended the First Mithridatic War.

Map of the First Mithridatic War

Map of the First Mithridatic War

Second Mithridatic War (83-81 BC)

Both Dardanian peace and Rome, and Mithridates perceived not as a final peace, but only as a truce before the next war.

After concluding peace, Mithridates retreated to Pontus, where he fought with the Colchians and the inhabitants of the Bosporus, who had fallen away from him.

Sulla fought in Italy with the Marians, and his successor in the East - Lucius Licinius Murena, dreaming of glory, in 83 BC, under the pretext that the Pontic king was preparing for war with Cappadocia, began military operations against him. Thus, the Second Mithridatic War began. In the very first battle on the shores of Galis, Murena was defeated. Murena retreated to Phrygia, and Mithridates to Colchis.

Then a series of insignificant battles occurred. At this time, Sulla managed to defeat the Marians in Italy and became a dictator. He ordered Murena to stop the war in 81 BC, which he did.

Thus ended the Second Mithridatic War.

Third Mithridatic War (74-63 BC)

In 75 BC, the King of Bithynia, Nicomedes IV, died, bequeathing his kingdom to Rome.

Mithridates used the death and will of Nicomedes as a pretext for a new war and attacked Bithynia in 74 BC.

Mithridates, as at the beginning of the first war, chose the moment and situation successfully.

Rome at this time was at war with the former supporter of Gaius Marius, Quintus Sertorius, who had entrenched himself in Spain and was able to raise the local population to war against Rome.

Mithridates made an alliance with him, also managing to involve pirates in this alliance.

Rome sent troops against Mithridates, led by the consuls of 74 BC, Marcus Aurelius Cotta and Lucius Licinius Lucullus, who was a friend and associate of Sulla, and already had experience of war with Mithridates.

Since the consuls led two armies, the first to meet with the army of Mithridates (20,000 infantry, 16,000 cavalry, and 100 chariots) was the army of Consul Cotta, which Mithridates defeated in naval and land battles and locked up with the remnants of the army in the city of Chalcedon.

Lucullus, with his army, learning about this, rushed to help his colleague in Bithynia. Mithridates, learning about this, moved with his army to meet Lucullus, to Phrygia. There he besieged the city of Cyzicus, but unsuccessfully and retreated by sea to Parii. Meanwhile, Lucullus, pursuing the retreating land army of Mithridates in Bithynia, managed to defeat it.

Thus Mithridates lost almost all his land army, but preserved his fleet.

However, in 73 BC, due to a severe storm, part of his fleet was lost, and he himself took shelter in Nicomedia (a city in Asia Minor, the center of the region of Bithynia, located today not far from Constantinople - Istanbul) with the remaining ships.

Here the consul Cotta besieged Mithridates. Mithridates managed to send his squadron to aid the slave Spartacus who had rebelled in Italy, but Lucullus, upon learning about it, intercepted it near the island of Lemnos and destroyed it.

As a result, breaking through Nicomedia with a fight, Mithridates fled by sea, but again got caught in a sea storm, which finished off the remnants of his fleet. Mithridates, having lost both the fleet and the land army, arrived in Amisus, from where he asked for help from the rulers of Parthia, Armenia, and the king of the Scythians.

Only Mithridates' son-in-law, the king of Armenia, Tigranes II, agreed to help.

In the meantime, Lucullus had taken over all of Bithynia, from which he moved to Pontus.

Here in the spring of 72 BC, in a series of skirmishes with Mithridates' last land army, Lucullus managed to defeat it. Mithridates fled to his son-in-law Tigranes II in Greater Armenia, and all of Pontus came under the control of Rome.

At first, Lucullus, through an embassy to Tigranes II, asked him to hand over Mithridates to Rome, but he refused, and then Lucullus began preparing for an invasion of Greater (Great) Armenia.

In the spring of 70 BC, Lucullus, with an army of 15,000 men, invaded Greater Armenia, which was a surprise for Tigranes II.

Lucullus moved to the new capital of Tigranes II, the city of Tigranocerta (modern city of Silvan, in Turkey), along the way defeating the squad sent against him by Mitrobazanes, a general of Tigranes II.

Tigranes II himself left the capital to gather troops. But in 69 BC, a battle took place near the walls of Tigranocerta between the armies of Lucullus (10,000 men) and the Armenian king Tigranes II (up to 200,000 men). Tigranes lost the battle and retreated to Taurus, where he began to gather new troops with Mithridates, while Lucullus entered his capital, looted it, and claimed 8,000 talents of gold as spoils.

Mithridates, having managed to convince Tigranes to continue the war after suffering defeats and losing the new capital, began to avoid open battles with the Romans by attacking their lines of communication.

Soon, after crossing the Taurus, Lucullus moved to the old (ancient) capital of Armenia, the city of Artaxata (now the city of Artashat in Armenia) on the Araxes River in 68 BC. Here he again defeated Tigranes, but failed to take Artaxata.

Moreover, in Lucullus's army, as in Rome, there was growing dissatisfaction with him and his actions during the war.

In Rome, opponents of Sulla came to power, who began to convince the people to recall Lucullus, who was only delaying and not ending the war, and was also an ally of Sulla. The knights, whose financial activities in Asia he had curbed, also spoke out against Lucullus.

In his army, the soldiers were dissatisfied with the difficulties of the campaign in the mountainous country and the strict discipline established by Lucullus, who himself lived almost like a king. As a result, discipline in his army fell and the troops were close to mutiny.

Under these circumstances, in 67 BC, Lucullus was replaced as the commander of the army. He was replaced by the consul Manius Acilius Glabrio. Lucullus left for Rome.

Mithridates decided to take advantage of the circumstances that were so favorable for him. He went on the offensive, reclaimed Pontus, Cappadocia, and threatened the province of Asia.

In these circumstances, Rome again replaced the commander of the Roman forces in the East. This time, at the beginning of 66 BC, the Roman forces in the East were led by Gnaeus Pompey Magnus.

Pompey attempted to settle the matter peacefully by offering Mithridates to surrender, but he refused.

Then Pompey began to prepare forces to continue the war. He replenished Lucullus's troops with fresh reinforcements, bringing his army to 40-50 thousand people, and made an agreement with Parthia to distract Tigranes from aiding Mithridates by attacking Armenia. In return, they promised to transfer some territories in Mesopotamia to Parthia.

Mithridates assembled a new army, but was defeated by Pompey in a night battle and fled again to Armenia, but Tigranes did not accept him because he himself had to flee to the mountains, escaping from the invasion of the Parthians, with whom Pompey had negotiated.

Thus, Mithridates lost his ally Armenia and after spending the winter of 66/65 BC in Colchis, he barely made it to the Bosporan Kingdom at the beginning of 65 BC, where his son Machares, who had rebelled against Mithridates, ruled. Mithridates overthrew and killed Machares.

Here he began to prepare a new army, wishing to unite the barbarian tribes of the Northern Black Sea region and the Danube against Rome and invade Italy with them.

In the meantime, he again attempted to negotiate peace with Pompey, but the latter demanded the same thing and the negotiations, leading to nothing, ended in a stalemate.

To carry out his plan, Mithridates needed money to pay the barbarians, but he could only gather 36,000 men and a fleet.

Mithridates began to forcibly take money from his Bosporan subjects, which ultimately led to a revolt against him by the major Greek cities of the Bosporan Kingdom - Phanagoria (on the Taman Peninsula), Chersonesus, Theodosia and other cities.

In response, Mithridates began executions. As a result, the rebels were led by another son of Mithridates, Pharnaces, who was supported by the army and fleet, while Mithridates himself was besieged in the royal palace, in his capital Panticapaeum (now the city of Kerch, Crimea, Russia).

At this time, in 65-64 BC, Pompey defeated Tigranes II and forced him to make peace with Rome, and also subdued, albeit formally, Mithridates's allied tribes of Transcaucasia and finally subjected Pontus to the power of Rome.

In 63 BC, seeing that all was lost, Mithridates ordered his bodyguard to kill him.

Thus ended the Third Mithridatic War.

Antique coin of the first century BC depicting the King of Great Armenia Tigran II the Great. Private collection.

Antique coin of the first century BC depicting the King of Great Armenia Tigran II the Great. Private collection.

Results of the Wars

As a result, Mithridates died, and his kingdom was divided into several parts, between the Roman Republic; Rome's allies and Mithridates VI's son, Pharnaces II.

- The Roman Republic formed the Roman province of Bithynia and Pontus from parts of the territories of Pontus;

- Rome's allies received parts of the territories of Pontus;

- Pharnaces II got the Bosporan Kingdom and the Tauric Chersonesus, except for Phanagoria, which became an independent city for betraying its father.

Pharnaces II ruled the Bosporan Kingdom from 63-47 BC. In 47 BC, he began to fight with Julius Caesar, lost to Caesar, and soon died. In Asia Minor, Pompey restored or newly created a number of independent principalities under the supreme authority of Rome (Cappadocia, Paphlagonia, Galatia).

Memory of Mithridates in Culture

Many books and works have been written about Mithridates, from antiquity to our modern times. Here are some of the works about Mithridates: Sallust's "Letters of Mithridates"; Jean Racine's tragedy "Mithridate" (1672); Mozart's opera based on Racine's tragedy "Mitridate, re di Ponto" (1770); the book "Purple and Poison" by A. Nemirovsky, a Soviet-Russian historian of antiquity (1973); Colin McCullough's novel "The Battle for Rome" (1991); Joseph Brodsky's "Cappadocia" (1993), and others.

Also, the Mount Mithridat in the city of Kerch and the city of Yevpatoria, which in the late 18th century (1784), when Crimea passed to Russia and the fortress-city Kozlov was renamed Yevpatoria, in honor of Mithridates VI Eupator, remind us of Mithridates.

Similar Topics

Roman Republic, Lucius Cornelius Sulla

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Appian. "The Mithridatic Wars".

2. Diodorus of Sicily. "Historical Library".

3. Plutarch. Comparative and selected biographies.

4. Strabo. Geografiya [Geography], Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1964. Epitome of Pompey Trog's work "The History of Philip", Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1964.

Contemporary authors:

1. McGing B. C. The foreign policy of Mithridates VI Eupator, King of Pontos. Leiden, 1986;

2. Saprykin S. Yu The Pontic Kingdom: The State of the Greeks and Barbarians in the Black Sea region, Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1996, 348 p.

3. Saprykin S. Y. Religion and cults of Pontus of Hellenistic and Roman times. 2009. Makging B. At the Turn: History and Culture of the Pontic Kingdom // Bulletin of Ancient History. 1998. № 3;

4. Saprykin S. Yu. Women-rulers of the Pontic and Bosporan kingdom (Dynamius, Pythodoris, Antonia Typhen) / / Woman in the ancient world, Moscow, 1995.

5. Gabelko O. L. Critical notes on the chronology and dynastic history of the Pontic Kingdom // Ibid., 2005, No. 4;

6. Mithridates VI and the Pontic Kingdom / Ed. J.-M. Højte. Aarhus, 2009.

7. Pearl City Eras of the Bithynian, Pontic and Bosporan Kingdoms / / Bulletin of Ancient History. 1969, No. 3, pp. 39-69.

8. Pontic Wars. Military encyclopedia in 18 volumes. Edited by V. F. Novitsky and others, St. Petersburg, 1911-1915.

9. Saprykin S. Yu., Academician M. I. Rostovtsev on the Pontic and Bosporan kingdoms in the light of the achievements of modern antiquity // Bulletin of Ancient History. - 1995. - No. 1. - pp. 201-209.

10. Eliseev M. Mithridates against the Roman legions. This is our war!. Moscow: Eksmo Publ., 2013, 320 p. (Prehistory of Russia) 11. Molev E. A. Vlastitel Ponta [The Ruler of Pontus]. Monograph. Nizhny Novgorod: UNN Publ., 1995, 195 p. (in Russian)

12. Naumov L. Mitridatov's Wars, Moscow: Magic Lantern, 2010, 512 p. 13. Talakh V. N. Born under the sign of a comet: Mithridates Eupator Dionysus / Ed. by V. N. Talakh, S. A. Kuprienko. — 2nd, additional and revised edition. — Киев: Видавець Купрієнко С. А., 2013. — 214 с.

14. Chernyavsky S. Mithridates the Great — Moscow, 2016.