Struggle Between Paganism and Christianity

The history of Christianity in the Roman Empire spans from the emergence of Christianity in the first half of the 1st century to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. During the 2nd century, Christianity spread throughout much of the Roman Empire, with extensive apologetic literature emerging, as well as letters and writings from authoritative Christian authors.

The transformation of the Roman Empire from a pagan to a Christian state occurred gradually over several centuries, and can be divided into the following eras:

- The Era of the Birth and Initial Development of Christianity in the Roman Empire under the shadow of Judaism, up to the Jewish revolt and the second destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (half a century after the death of Jesus Christ);

- The Era of Sporadic Persecutions (under Domitian, the Antonines, and the Severans);

- The Era of Universal Persecutions, aimed at the destruction of the Christian Church (during the tumultuous period and under Diocletian);

- The Era of the Ascendancy of Christianity and the Decline of Paganism (from Constantine the Great to the 6th century).

The Birth of Christianity

The pagan world’s internal readiness to accept Christianity was influenced by the development of pagan religion, philosophy, and science.

Regarding the development of pagan religion, during this period, it was a very diverse phenomenon with three main directions: Hellenic, Roman, and Eastern. The first, Hellenic, is further divided into two currents: the overt current of civic cults and the covert current of mysteries. The overt Hellenic religion was fundamentally hostile to Christianity; its distinct polytheism was as stark a denial of Christian monotheism as its civic character was of Christian universalism. However, this enemy was no longer as dangerous as in the times when Delphi wielded significant influence in the Greek world to unite it under the banner of Apollo's religion. By this time, Delphi's influence had diminished significantly, Greek polytheism, weakened since the loss of Greek independence by many profanations and the corrosive influence of philosophical thought, no longer held strong convictions among believers, and in the minds of many (of whom there were many) was ready to give way to the recognition of a single deity, represented either as inscrutable chance (Tyche, which particularly developed during the dynastic wars among Alexander the Great’s successors), or as fate (Moira), governing the movements of celestial bodies and through them human life, or as providence (Pronoia), or finally simply as "divinity," "god," "gods" (theion, theos, theoi), without regard to number or qualities.

Thus, while overt Greek religion was in a state of decline and did not pose a significant obstacle, the covert religion of mysteries (not so much the Eleusinian as the Orphic) was widely popular; but it also significantly prefigured Christianity and thus paved the way for it. At its core, Orphism included the myth of the suffering god-savior, Dionysus Zagreus, who was torn apart by the Titans, and the myth of resurrection (Eurydice — by Orpheus); it directed the attention of believers (in contrast to the overt religion with its unrealistic dogma of restoring justice on earth) towards the afterlife, promising eternal bliss to the good and eternal and temporary punishments to the wicked, while developing practices of fasting, purification, and cleansing, through which one could prepare for a better fate beyond death during one's earthly life.

The supremacy of the mysteries over the overt cults was the driving force within Hellenic religion that contributed to the Christianization of the empire; but the Roman direction of the imperial religion also aligned with this movement, albeit through a different path. Roman polytheism, in contrast to Greek, was characterized by complete ambiguity, both qualitative and quantitative, and was therefore inclined toward integration, the result of which was the worship of an all-encompassing deity. During this period, this deity was often represented by the "genius" of the reigning emperor (which in principle was far from identical to the deification of the emperor himself, but in practice often came down to it), which foreshadowed two dogmas of the Christian religion at the same time — firstly, its monotheism; secondly, its teaching on the God-Man. Regarding this latter point specifically, it can be said that it was precisely due to this that Christianity became as natural a religion of Greco-Roman culture as it was incompatible with Judaism.

Finally, the third — Eastern — direction of pagan religion, which at that time had also dominated the western half of the empire, was as such destined to prepare the way for Christianity, whose cradle also lay in the East. In general, it can be said that the Eastern cults, in their inclination towards Christianity, combined, though not entirely, the characteristics of Roman and Greek cults. While Roman religion by its nature tended towards monotheism, the Eastern deities rooted in Rome (the Great Mother of the Idæan, Isis, the Cappadocian Ma or Bellona, the Invincible Mithra) were either singular themselves or so predominant that other deities seemed to dissolve into them. On the other hand, while Greek secret cults awakened in man a consciousness of his sinfulness and a thirst for redemption, the Eastern cults fulfilled the same task but through much more spectacular and therefore much more impactful rituals. In this regard, the religion of Mithra the Invincible, Persian in origin, had a particular influence: Mithraism was the most active, if not the most dangerous, competitor of Christianity. But the cult of Mithra was especially widespread in the western half of the empire; conversely, Christianity became a predominant religion in the eastern part of the empire much earlier than it was recognized as a religion of equal status throughout the state; thus, the struggle between Mithra and Christ also amounted to a struggle between the West and the East, between Romanism and Hellenism.

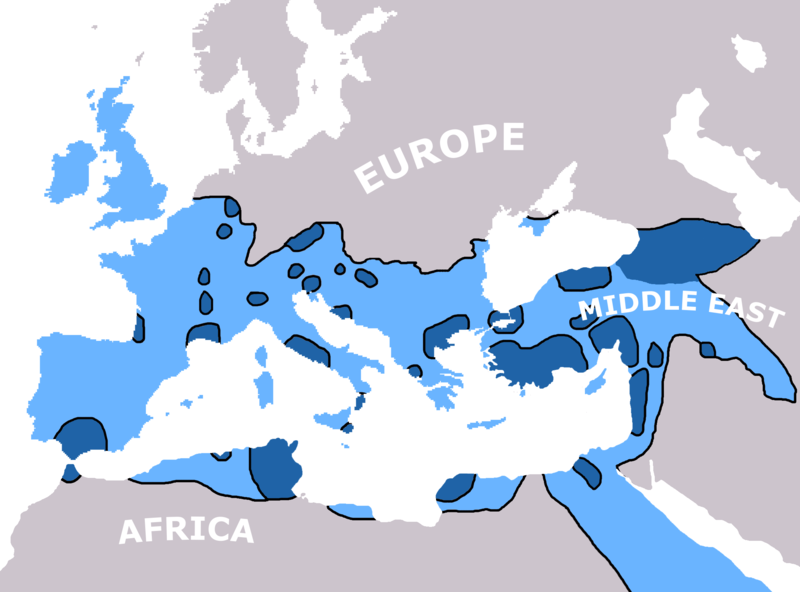

Dark blue: Spread of Christianity by 325 AD Light blue: Spread of Christianity by 600 AD

Dark blue: Spread of Christianity by 325 AD Light blue: Spread of Christianity by 600 AD

Early Development of Christianity Under the Influence of Judaism (until 80 AD)

Let's attempt to trace the fate of Christianity from the point where it emerges within the "diaspora." It is naturally impossible to specify the exact time of its birth in various cities or the direction of its spread. Its simultaneous or almost simultaneous emergence in several locations is not surprising, given the context mentioned earlier. Based on geographic considerations, one might surmise that the main route for the spread of Christianity was a line leading from Jerusalem through Antioch to Asia Minor (mainly Ephesus), branching off towards Macedonia (Philippi, Thessalonica) on one side and Corinth, Puteoli, and Rome on the other. However, this is merely a construction.

The centers of the birth of Christianity, as mentioned earlier, were Hellenized Jewish communities, which is why the initial language of Christianity, even in Rome, was Greek. If these communities had been of a strict type, as they became after the Bar-Kochba revolt (i.e., under Emperor Hadrian), Christian groups would inevitably have taken on the form of "synagogues." But at that time, due to the various degrees of proselytism, the organization allowed for significant liberties. Given the negative attitude of Judaism towards Christianity, which had already formed in Jerusalem, it was natural that the new teaching would take root more quickly among proselytes than among Jews themselves.

A unified, strict organization of Christian communities in the early stages was therefore impossible. During the first decades of Christianity's existence on Roman soil, these communities presented a fairly diverse picture. We encounter:

a) Christians who were, so to speak, particularists, like those metuentes sabbata, who constituted the first degree of Jewish proselytism: they were satisfied with exchanging the Jewish Sabbath for the Christian Sunday while otherwise living their usual lives.

b) Christian groups without any formal organization, "guided by the Holy Spirit."

c) Clearly and more or less strictly organized Christian communities. At the same time, we see that the efforts of Christian teachers were directed towards transforming the first two types into the third; they consistently reminded believers that a Christian could enjoy the spiritual gifts of their religion only as a member of a Christian community. And if we remember that the prototype of the Christian community—directly or indirectly—was the collegium, it turns out that the enforcement of non-political organization was implemented much earlier on spiritual grounds than on secular ones, while the principle of unity, on the contrary, arose on secular grounds and was only later transferred to the spiritual sphere. There was no conscious borrowing in either case, but rather a common Roman-imperial spirit.

When discussing the organization of the first Christian communities, we must first address their relations with the Jewish communities from which they emerged, as well as with the surrounding pagan environment. As for the relationship with Jewish communities, the apostolic word, although it was first proclaimed in synagogues, was not accepted by them.

The first Christian communities consisted of three elements:

a) Jews who had fallen away from the synagogue.

b) Jewish proselytes who had exchanged Judaism for Christianity.

c) Former pagans who had converted to Christianity outside of Judaism.

Over time, the first group became overshadowed by the second, and both were overshadowed by the third. The Christian community encircled the Jewish community (or rather, it formed a second ring, the first being the proselytes). To an outside observer, it coincided with the core—Christians were considered a Jewish sect and participated in Jewish privileges, the most valuable of which for them was exemption from participation in obligatory pagan cults, primarily the cult of the emperor's genius. In reality, however, they were independent of the synagogue and governed themselves. In cities where there were several synagogues, there must have been several Christian communities; perhaps this was initially the case, but for us, the Christian community in each city represents a single entity. The separation was accompanied by hostility: very soon, synagogues, which had been centers of Christianity, turned into "sources of persecution" (fontes persecutionis) against it. Under such circumstances, the Roman authorities' confusion of Christianity with Judaism seems to us puzzling, understandable only through complete disregard for both.

The Apostle John the Theologian Preaching on the Island of Patmos During Bacchanals

The Apostle John the Theologian Preaching on the Island of Patmos During Bacchanals

The separation of the Christian community from the surrounding pagan environment was less strict—less strict even than the separation of Jewish communities from it. Among the possible forms of dependence of a Christian on the pagan environment—civic, class, social, legal, and familial—the first three remained untouched: the Christian remained a citizen of his community and bore its burdens; a slave continued to serve his master (even joining the Christian community, according to Roman concepts of collegia, only with his master's consent); the convert was not forced to avoid interaction with his former pagan acquaintances. The fourth form also remained unchanged; only disputes between Christians were dealt with within the community itself, following, perhaps without direct borrowing, synagogue traditions.

The only serious difficulty was the fifth form, particularly in the case of mixed marriages. The synagogue, in theory, did not recognize them, though in practice it allowed exceptions to avoid conflicts; the Christian community did the opposite—in theory, it recognized mixed marriages but, in each individual case (given the practical inconveniences of such a situation, especially for the Christian wife), it tried to bring about either the conversion of both spouses or a divorce. Regarding the organization of the community itself, we must distinguish between two elements: a) the element characterizing it as a collegium, and b) the element characterizing it as a center of Christianity.

To the first belonged:

1. The head of the entire community, the "bishop." Like synagogues and unlike Roman collegia, Christian communities were governed on the principles of monarchy rather than collegiality (though in the early days, bishops or presbyters were sometimes found in the plural).

2. An indefinite number of "deacons," comparable to curators of collegia; their importance was determined by the significance of Christian charity.

3. An indefinite number of "presbyters," analogous to decurions of collegia; they apparently formed something like a community council (though where there were several bishops, they probably coincided with presbyters).

4. The assembly of all members of the community—the "ekklesia," which gave its name to the entire Christian Church.

To the second element, which transitioned into Christian communities from Judaism, belonged:

1. Apostles.

2. Prophets.

3. Didaskaloi (teachers), of whom only the latter were permanent and belonged to a given community.

Their task was to spread Christ's teachings and to nurture the communities in that spirit: evidence of this activity is preserved in the pastoral letters of the apostles and apostolic fathers. However, we should not imagine this organization as uniform or too strict in the first period: all communities, even the best-organized ones, were governed by the Holy Spirit, and the importance of each factor depended on how much it was considered to be influenced by the Spirit. For information on the religious and intellectual life of the first communities, their gatherings, and their struggles with hostile movements (mainly Judaistic propaganda and early Gnosticism), see the previous and following articles.

Finally, when discussing the relationship between Christian communities, we touch upon the question of whether it is possible to speak of the Christian Church as such during the first era of Christianity. The answer can be either affirmative or negative, depending on whether we consider the internal unity of doctrine and sentiment and the lively communication between communities, or the external unity of organization. From the first perspective, one can and should say that all communities formed a single Christian Church: all members of the communities were aware that they belonged to it, not to a local sect; the exchange of news and opinions between communities was very lively—thanks to the travels of apostles and prophets, and to the widespread practice of hospitality.

But from the second perspective, it must be acknowledged that the Church did not yet exist either in the form of a singular leadership or in the form of a council of representatives. The Church was governed by the Holy Spirit. This is not surprising in an era when even within individual communities, organization was just beginning to emerge. Nonetheless, one can say that even in the first era, the organization of the Church, in the sense of its centralization, was in oriente domo. Moreover, just as in individual communities, the organization gradually developed on the basis of the episcopal element and at the expense of the apostolic one, in the broader Church, the emerging apostolic leadership gradually faded and gave way to the rising dominance of one central community and its leader-bishop over others. Indeed, at first, apostolic leadership was undeniable, but it did not lead to unity. Apart from the Roman community, which recognized the Apostle Peter as its founder, we distinguish a circle of communities founded by the Apostle Paul (in Greece proper, with Macedonia and Asia Minor) and another circle centered around the mysterious figure of the Apostle John (in Asia Minor). In later development, we observe clear signs of attempts by the Roman community to elevate itself above the others: in the pastoral letter to the Corinthian community, its leader (by tradition, the Roman bishop Clement) demands obedience from it in the name of the Holy Spirit. Thus, even in this era, the main path along which the development of the Christian Church would proceed over the next centuries was already beginning to take shape.

The Era of Sporadic Persecutions (80–235)

The era of sporadic persecutions, spanning from Domitian to the death of Alexander Severus (80–235 AD), marks a significant period in early Christian history. During this time, Christianity, having fully severed its ties with Judaism, began to attract the attention not only of Roman authorities but also of Roman society at large.

By the beginning of this period, Christianity had spread extensively across various regions, presenting the following picture: In Palestine, Christian communities (or groups) could be found not only in Jerusalem but also in Samaria, Joppa, Lydda, and Sharon (i.e., Caesarea Maritima); in Syria, besides Antioch, there were communities in Damascus, Tyre, Sidon, and Ptolemais; on Cyprus, in Salamis and Paphos; in Asia Minor, the most Christianized region of the ancient world, in addition to Ephesus and the other six communities mentioned in the Apocalypse (Smyrna, Pergamum, Thyatira, Sardis, Philadelphia, and Laodicea), there were communities in Tarsus, Perga, Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra, Derbe, Colossae, Hierapolis, and several other cities in Galatia, Cappadocia, and the Troad whose names remain unknown to us; in Macedonia, besides Thessalonica, there were communities in Philippi and Berea; in Greece proper (Achaia), besides Corinth, there were communities in Athens and the port of Cenchreae; on Crete; in Italy, besides Rome, in Puteoli; and in Egypt, only in Alexandria (in all these locations except the last, the existence of Christian groups and communities is attested in the New Testament). From this picture, it is evident to what extent Greek was the language of Christian preaching during the entire first period of Rome's Christianization: the entire West remains untouched, leaving space for the spread of Mithraism, the cult of the Unconquered Mithras.

During our period, the territorial spread of Christianity in the eastern regions intensified, and the following cities were added to those mentioned above: in Syria, a number of cities including, no doubt, Seleucia; in Asia Minor, a large number of communities, including Magnesia, Tralles, Philomelium, Parium, Nicomedia, Otryae, Pepuza, Tymion, Apamea, Cumae, Eumenia, Ancyra, Sinope, Amastris, and those Bithynian communities, whose names are not specified, about which Pliny the Younger wrote to Trajan; in Thrace, Debeltum and Anchialos; in Greece, Larissa, Laconia, and Samos (on Cephalonia); on Crete, Knossos and Gortyna. The East was also joined by the West in the form of Italy with Sicily (Naples, Syracuse), Gaul (Lyon, Vienne, several communities in central Gaul), Africa (Carthage), Numidia (Madauros, Scillium), Germany (Colonia = Cologne), and Spain.

As for the intensity of Christianity's spread, that is, the density of the Christian population in the empire, we lack sufficient information; the most valuable testimony comes from Origen, who lived towards the end of our period. He indicates that Christians in the empire were still comparatively "very few," though they formed a "large crowd" compared to their initial small numbers, and that there was not yet a single city in the entire state that was genuinely Christian. He only provides a number for Judeo-Christians (about 150,000). It is interesting, however, to trace the spread of Christianity in various layers of Roman society. In the apostolic era of Paul, Christianity was mainly confined to the lower, obscure classes; the participation of educated and high-ranking individuals was the exception. Now, Christianity began to attract people from higher circles as well. Regarding the intelligentsia, especially among the Gnostics, we find highly educated and talented individuals; among the Orthodox, Clement and Origen, who lived towards the end of the period (80–236 AD), were worthy representatives of Christian scholarship. As for the nobility, evidence of the conversion of officials of senatorial and equestrian rank is so frequent that we must imagine Christianity of this era as a religion almost equal in social status to paganism. The conversion of close relatives of Emperor Domitian at the very beginning of our period was particularly striking—consul Titus Flavius Clemens and his wife Domitilla—especially since their sons were designated heirs to the throne. They were severely punished by Domitian in 95–96 AD, and this punishment led to Domitian's death at the hands of Domitilla's servant (though there is no mention of him being a Christian). The ascension of a Christian emperor was postponed for many years. However, among the emperor's close associates, freedmen, and slaves, a known number of Christians were present at all times; by the end of the 2nd century, we encounter a sort of Christian Esther—Marcia, the mistress of Emperor Commodus—through whose patronage Christians received many benefits. The Roman bishop Victor was in contact with her and, through her influence, managed, among other things, to secure the release of Christians working in the mines of Sardinia.

It is useful to note here the influence of this intellectual and social aristocratization of Christianity on its character; the first manifested in the introduction of a strong intellectual element, which elevated it to the status of a religion of reason but also contributed to the emergence of many heresies; specifically, the Hellenization of Christianity, both outside and within the Orthodox framework, was its doing. The second resulted—among other causes, however—in the nature of the Christian hierarchy, which will be mentioned below.

Conflicts of a special kind were caused by Christians' membership in the military. In the early period, this was not an issue: since Christians were considered Jews, and Jews were exempt from military service, we rarely find Christians in the army (we say "rarely," as conversions of soldiers were possible even then). But now the Jewish mask was removed, Christians were Roman subjects like everyone else, and they were subject to conscription; the question of the compatibility of Christianity with military service arose. Since this question concerned the higher military authorities, it will be addressed later; Christians themselves had mixed views on it. The strict ones resolved it negatively, citing:

a) The soldier's duty to shed blood;

b) The pagan nature of the military oath; and

c) The fact that the Savior himself disarmed the Apostle Peter.

But there were also more conciliatory interpretations, based on John the Baptist's address to soldiers, the centurion of Capernaum, and the centurion at the cross. There was no single resolution; soldier-martyrs appeared in all times, but alongside this, the number of Christians in the military, especially in the eastern legions, continued to grow.

The development of the internal organization of Christian communities and the Christian Church during this period followed the path outlined in the corresponding section of the previous paragraph; the changes brought about by this development were very significant. As mentioned earlier, Christian communities contained a dual element, general collegial and specifically Jewish, both of which could be integrated into the community hierarchy: these were a) bishops, presbyters, deacons, and b) apostles, prophets, and teachers. The second element was the bearer of spiritual enthusiasm and ecstasy, while the first was associated with sober civic activity. Initially, the second element predominated; reading the epistles of the New Testament gives the impression that it was this element that was destined to unify the church; however, things turned out differently, and by the end of the period, the second element (except for teachers) was already removed from the church. Later tradition represented this removal as a peaceful act. According to Theodore of Mopsuestia, the apostles initially took on leadership over entire regions, leaving the communities to the bishops; the apostles of the second generation, feeling themselves unworthy of the name and task of their predecessors, voluntarily stepped down. Specifically, according to Roman tradition, the Apostle Peter, the founder of the Roman community, in anticipation of his imminent martyrdom, ordained his assistant and companion Clement as the Roman bishop. Whatever the case, the fact remains that the organization of the church now develops according to the first, not the second element. But even here, there were not one but two possible paths. Roman collegia, as we have seen, were governed not by one person but by a collegium of "masters"; Jewish synagogues, having generally adopted the type of collegial organization, modified it towards autocracy, with a single "archigerusiast" at the head. Christian communities initially vacillated between the two principles, being led either by a single "bishop" or by several "leaders" (hegoumenoi; however, this was unlikely their technical name, and there is reason to believe they were called either presbyters or bishops). Moreover, with the freedom of the early organization of communities led by the Holy Spirit, even the presence of a bishop did not make them monocentric: frequently, the bishop, as primus inter pares, managed the community's affairs along with the presbyters.

Now, as the initial enthusiasm waned, the question of organization became pressing: what form should it take—monocephalous or polycephalous, in other words, episcopal or presbyterian? This question was resolved differently across various communities: for example, the Alexandrian community was governed presbyterially for a good portion of this period. However, the overall development of the Church led to the consolidation of the episcopal system. “Obey your bishop!”—this was the ceterum censeo in the pastoral letters to the communities from the “Apostolic Man” Ignatius, who lived at the beginning of the period under consideration. Thus, the Christian Church had already gone through all three types that have been repeated in different confessions and sects throughout its history—the apostolic-prophetic type, the presbyterial type, and the episcopal type. The latter ultimately triumphed for various reasons, the main ones being as follows: (a) foresighted men, aiming for the unification of the Church, could not help but notice that such unification would be much easier to achieve with an episcopal rather than a presbyterian organization of individual communities; (b) the infiltration of the Christian communities by the aristocracy also had the practical consequence (though theoretically this was not allowed, of course) of the most noble member taking on a leadership role; (c) with the disappearance of the apostolate, the responsibility for maintaining the purity of Christian doctrine passed to the bishops, which also favored the singularity of the episcopate, as otherwise, disagreements—and with them, disorder and scandal—would have been inevitable; it was precisely the struggle against heresies that highlighted the advantages of a single bishop’s authority. Be that as it may, during this period, the hierarchy of Christian communities began to take shape: the lowest level was occupied by deacons, the middle by presbyters, and the highest by bishops. We also begin to see signs of these individuals being distinguished as a separate clerical estate—the clergy; this distinction is connected to the question of priesthood, which was also resolved in two ways, either in the sense of communal representation or in the sense of apostolic succession. The first solution is based on the principle that the entire community is inspired by the Holy Spirit and, therefore, is capable of electing its leaders; the second solution is based on the principle that the source of the priesthood is the Savior Himself, through Him—His apostles, and through them—those ordained by them.

The entire period was marked by the struggle between these two principles, with the same factors that contributed to the development of organization in the direction of episcopalism (mainly the waning of initial enthusiasm) also contributing to the resolution of the priesthood question in favor of apostolic succession. This decision solidified the privileged position of those communities in which apostolic succession had never been interrupted by the principle of communal representation, namely, the Roman community. All of this development significantly prepared the way for the unification of Christian communities, that is, the formation of the Christian Church, which occurred, as previously mentioned, around 180 AD. The immediate cause was the Montanist heresy (see the relevant entry); the situation unfolded as follows. With the decline of the apostolic and prophetic elements, the expectation of the Second Coming of the Savior, which had inspired Christians during the first period, began to give way to the belief in the longevity of the world and the necessity of considering its demands. This sobriety of mind was correlated with the strengthening of episcopalism. The suppressed elements of prophetic ecstasy and eschatological expectations burst forth in Montanism, around the middle of the 2nd century in Asia Minor. It is understandable that the Montanist crisis took on an anti-episcopal character and united the episcopal communities against it. The method used to address this was the so-called synods, in which initially bishops, along with other community delegates, participated, and later only bishops. The Asian Minor communities were the first to hold anti-Montanist synods—the first ones known to us; later, both parties sought the support of the Roman bishop Eleutherius, who expressed himself against the Montanists. This situation contributed to the aspiration of the Roman community and its bishop for primacy, which we have already observed in the first period. A particularly energetic advocate of Roman primacy was Eleutherius' successor, Victor (189-199).

At his initiative, provincial synods were convened on the question of Easter observance; their decisions were communicated to him, and he, in turn, circularly informed the provincial bishops of the decisions of the Roman synod. When all the communities, except those in Asia Minor, agreed with the Roman decision on the Easter question, Victor excommunicated the communities of Asia Minor from the Church as "heterodox" (heterodoxoi). Thus, the trend towards the organization of the Christian Church is outlined—from the Roman point of view, in its hierarchical aspect, and from the universal point of view, in its conciliar aspect. The hierarchical elements of this organization were:

1. the bishops of individual communities

2. metropolitans, that is, the bishops of the principal communities of each province (these "metropolises" were highlighted in our previous statistics)

3. the (future) pope, that is, the bishop of the Roman community

These three hierarchical levels correspond to three conciliar levels, namely:

1) to the bishop—the ekklesia, that is, the assembly of the members of the community, 2) to the metropolitan—the synod, that is, the assembly of the bishops of all communities centered on the metropolis, 3) to the pope—the ecumenical council, that is, the assembly of bishops of all Christian communities. The latter does not yet exist, but its absence is already felt.

It is understandable that in the absence of this conciliar structure, the importance of the corresponding hierarchical factor must have significantly increased; it is also understandable that with its establishment, an antagonism between the hierarchical and conciliar elements of church organization was bound to arise—but these were challenges for the future.

Third Period: The Era of Universal Persecutions (235–325)

The era of universal persecutions aimed at destroying the Christian Church, from the death of Alexander Severus to the establishment of Constantine the Great's sole rule (235–325).

The internal life of the Christian Church during this period will be examined from three perspectives: the extensive spread of Christianity, the intensive spread, and finally, the development of ecclesiastical organization.

Firstly, regarding the extensive spread of Christianity, it was during this period that Christianity gained a numerical superiority within the Roman Empire, which by the end of the period compelled the Roman Emperor to recognize it as equal to other state religions. Concerning specific provinces, the following can be said:

In Palestine, Christianity finally separated from its Jewish roots. The small community of Judeo-Christians, shunned equally by both Jews and other Christians, languished and eventually died out; Christianity survived only among the Hellenistic population of the country, and even there only weakly. It was only thanks to Constantine's support that Christians managed to gain control over the Holy Places. The metropolis was Caesarea; however, the bishop of Caesarea had a rival in the bishop of Aelia (Hadrian's city, founded on the ruins of Jerusalem with a prohibition against Jewish settlement) in leading the provincial synods.

In Phoenicia, the situation was not much better; here too, the pillar of Christianity was the Greek element in the coastal cities; within the country, we find Christianity only in Damascus, Palmyra, and Paneas, thanks to a strong percentage of Greek population. The metropolis was Tyre; however, Phoenician synods only became separate from the Palestinian ones during this period. Phoenicia sent eleven bishops to the first ecumenical council. In Syria was the capital of Eastern Christianity, the "beautiful city of the Greeks," as it was called—Antioch, from where the teachings of Christ began their journey into the pagan world. By this time, the city was already almost half Christian; in addition to provincial synods, great regional synods were also convened here, with up to 80 bishops from all over the East, from the Black Sea to Mesopotamia and Palestine. Christianity was also quite widespread in other Syrian cities; they sent 20 bishops to the Council of Nicaea.

From Cyprus, three bishops went to the Council of Nicaea; however, there were more of them; the details are unknown. In Egypt, thanks to the numerous Greeks and Jews, Christianity was widely spread: Christians numbered at least as many as Jews, that is, over a million. By the end of the period, under Athanasius, there were about a hundred bishops; around fifty episcopal sees are known to us; 29 bishops attended the Council of Nicaea. However, it was only during this period that Egypt transitioned from a presbyterial to an episcopal system, with bishops being appointed by the metropolitan, i.e., the bishop of Alexandria. In the 4th century, Christianity penetrated Abyssinia for the first time. In Cilicia, the metropolis was Tarsus, the birthplace of the Apostle Paul; the number of Christians was significant; Cilicia was represented by ten bishops at the Council of Nicaea.

The rest of Asia Minor was the most Christianized of all regions, just as it had earlier been the most devoted to the cult of the emperor; here it is clear how much the latter, in terms of a universal religion, was a preparation for Christianity. The metropolises were Caesarea (for Cappadocia), Nicomedia (for Bithynia), Ancyra (for Galatia), Laodicea (for Phrygia), Iconium (for Pisidia and Lycaonia), and Ephesus (for Asia Minor in the narrow sense). The spiritual center for a long time was Ephesus; it remains so during the period under consideration, but its significance within the wider Christian Church begins to shift towards Rome.

On the Balkan Peninsula, Christianization advanced slowly: in the north, wild tribes were not very receptive to the type of Christian preaching prevalent at the time (its characteristics are described earlier; the secret of Christian preaching to the barbarians was only discovered by Rome on the threshold of the Middle Ages); as for the Greek population, it showed much more attachment to its old religion at home than in the colonies and diaspora. Few Christian communities were added here beyond those mentioned in the previous section.

In the Danubian provinces, Christianity is only encountered during this period; for the reason mentioned in the previous point, it did not enjoy much success here either. In the eastern provinces (Moesia, Pannonia), Greek preaching competed with Roman, with the latter generally prevailing; the western (Noricum) was entirely dependent on Rome.

In Italy itself, including Sicily, Christianity was very widespread. Already in 250 AD, at a synod convened by Pope Cornelius against Novatian, 60 (exclusively Italian) bishops were present; thus, there were around a hundred in total, and the language of the Roman community had been Latin since the time of Pope Fabian (236–250); before him, Greek predominated; as we have seen, Pope Hippolytus was still a Greek writer.

In Northern Italy, the successes of Christianity were fairly modest: it leaned more towards the Balkan Peninsula than Rome. The western part was still largely pagan; of the eastern communities, the three main ones—Ravenna, Aquileia, and Milan (Mediolanum)—were only founded at the beginning of our period.

In Gaul (with Belgica, Rhaetia, and Roman Germany), the number of communities was not very large: from the lists of provincial synods in Rome (313) and Arles (316), we know that by this time there were about twenty bishops. The distribution of Christians was very uneven: in the south, the Christian population in the early 4th century apparently already set the tone—in Belgica, the most significant community, that of Trier, was still very modest in the same era.

Christianization of Britain occurred during this period; during the Diocletianic persecutions, Britain saw its first martyr, Alban, whose name is preserved in the town of St. Albans. The Synod of Arles (316 AD) included among its members three British bishops: those of London, York, and Lincoln.

For North Africa, from Tripoli to the ocean, this period marked the height of its prosperity and intense Christianization. The Carthaginian episcopal see was second only to that of Rome in the entire empire, a status significantly aided by the powerful personality of Bishop Cyprian (c. 250 AD). Even before him, the Synod of Carthage (c. 220 AD) gathered up to 70 bishops, and the Synod of Lambese (before 240 AD) gathered up to 90 bishops. By the beginning of the 4th century, there were already over 125 bishops. Geographically, the distribution of Christianity was almost as even as in Asia Minor, but ethnographically it was very uneven. "The speed of the spread of Christianity in these provinces matched the speed of its disappearance under the pressure of Islam. The native Berber population was either not Christianized at all or only superficially. The next layer of the population, the Punic, seems to have mostly become Christian, but since the Punic language was never a church language and there was no Punic Bible, its Christianization was not durable. The third layer, the Greco-Roman, probably accepted Christianity entirely, but it was too thin" (Harnack).

Christianity in Spain is known to us thanks to the acts of the Council of Elvira, which was attended by up to 40 bishops; it was quite widespread there, though its moral standing was not very high.

Regarding the intensive spread of Christianity during our period, it should be noted that the ancient episcopacy was far different from the current one; various precise data indicate that bishoprics with 3,000–4,000 members were not uncommon, and there were even bishoprics with as few as 150 or even fewer members (still in the late 4th century). We have numerical data only for the Roman community, from which it is clear that under Pope Cornelius (c. 250 AD), the Roman Church had 46 presbyters, 7 deacons, 7 subdeacons, 42 acolytes, 52 members of the lower clergy (exorcists, readers, and doorkeepers), and over 1,500 widows and poor. By 300 AD, there were over forty churches. Based on this, Harnack estimates the Roman community numbered 30,000 members; its significance is eloquently demonstrated by the words of Emperor Decius, who said he would sooner reconcile with a rival emperor in Rome than with a rival bishop. Regarding the spread of Christianity across different social strata, it is enough to refer to what was said in the previous section, adding that the difference between the cultural level of paganism and Christianity during our period had almost disappeared; this is evident from the attention the Neoplatonist philosopher Plotinus paid to Christian doctrines, compared to the disdain with which Celsus had spoken of the intellectual content of Christianity. It seems that the level of pagan and Christian culture was converging: the former declining, the latter rising.

Regarding the internal organization of the Church, it should be noted that after the victory of the Orthodox Church over the apostolic-prophetic reaction of Montanism, which marked the end of the previous period, the significance of the clergy as a distinct part of the community increased. The episcopate of Pope Fabian (236–250 AD) is noteworthy in this regard, as he established the lower clergy in five ranks (subdeacons, acolytes, exorcists, readers, and doorkeepers) and divided his community into 14 parishes, corresponding to the administrative division of Rome into regiones, assigning each parish one deacon or subdeacon. Shortly after Fabian, Pope Dionysius (259–268 AD) established dioceses (dioeceses) subordinate to his metropolitan see; this completed the ecclesiastical centralization of Italy in anticipation of similar centralization within the universal Church. This latter also advanced during our period: of the metropolises rivaling Rome, Ephesus had already been subdued by Pope Victor, as we have seen; now Rome had the opportunity to intervene in the affairs of the Antiochian church. There, a schism arose between the community and its ambitious bishop Paul of Samosata; at the suggestion of Emperor Aurelian, the Roman Pope was chosen as the mediator, and upon his judgment, Paul was deposed. Of course, these interventions were far from formal supremacy; Cyprian of Carthage did not recognize such supremacy, nor did other metropolitan and episcopal sees, defending their independence by referring to the unbroken apostolic succession among their bishops, for which apocryphal tables of bishops were drawn up all the way back to some apostolic founder.

Internal centralization within individual communities progressed during our period at the expense of communal self-government. The election of bishops by the community finally passed to the clergy, as the primary bearers of the gifts of the Holy Spirit. In some regions of the East, the institution of so-called chorepiscopi developed, that is, bishops over Christians scattered in various village communities; however, urban bishops viewed this institution unfavorably, and it gradually disappeared. There is no doubt that the persecutions of our period, directed mainly against the church's pastors, significantly contributed to the strengthening of the episcopate; martyr bishops were a characteristic feature of this period, and they sealed the authority and sanctity of their office with their blood. Another reason for the strengthening of episcopal power was the right of absolution, again confirmed and recognized for bishops following the victory over the Montanist heresy; a third was the right of the community to own property, granted not to the community as such, but to the bishop as its representative. The Christian Church with which Constantine the Great made his alliance was an episcopal Church, divided into metropolises and gravitating—though only gravitating—towards its Roman center.

The Era of Christianity's Supremacy Over Paganism

The fourth period marks the era of Christianity's supremacy over paganism and the gradual eradication of the latter, from Constantine the Great to Justinian. Theodosius I the Great persecuted representatives of ancient philosophy and religion, whom Christians considered pagans. In 384–385 AD, a series of decrees ordered the destruction of ancient temples, including the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, the Temple of Artemis Hemera, and others. The Prefect of the East, Cynegius, destroyed many of the remaining sanctuaries of the old faith. The Edict of 391 AD, even stricter, delivered the final blow to paganism, banning the worship of gods not only publicly but also in private homes. In Rome, the famous statue of Nike (Victory), regarded as the palladium of the ancient religion, was finally and permanently removed from the Senate chamber. The opposition of the old Roman nobility, led by Symmachus and Praetextatus, did not overturn Theodosius' decisions; the sacred fire of Vesta was extinguished (394 AD), and in the same year, the Olympic Games in Greece were held for the last time. In practice, paganism continued in remote corners of the empire.

During this period, Christianity and paganism essentially traded places (with the brief exception of Julian the Apostate's reaction).

After Christianity was legalized by Emperor Constantine the Great in 313 AD, and later elevated to the status of the state religion, the nature of Christianity drastically changed as it faced the challenge of internal secularization. A powerful influx of new converts poured into the previously small church communities, drawn not so much by Christ and the salvation He offered, but by the emerging social, material, and governmental benefits. The quantitative increase in the church flock led to a decline in the "quality" of these new adherents. The external boundaries of the Church (between the faithful, catechumens, penitents, and pagans) became blurred, while within the Church itself, existing and new barriers arose—between clergy, church officials, itinerant preachers, monks, wealthy influential laymen (including courtiers), and poor laymen (including slaves), as well as between Christians of different nationalities and hostile states, among others.

Clergy began to engage more frequently in commerce and sought privileges and positions from the state, leading to a resurgence of simony. Bishops, who had previously focused primarily on financial matters within local Christian communities (similar to today's parish wardens or wealthy benefactors), with the aid of state power, effectively seized full control of the earthly Church. They also banned and ridiculed the formerly revered itinerant preachers (who included itinerant teachers, exorcists, homeless "fools for Christ," apostles from earlier times, and others).

Some extreme zealots for the purity of Christianity believed that it was no longer possible to attain salvation in the world, so they withdrew to remote deserts, mountains, and forests, where they founded monasteries. However, the growing authority of monasticism led to its own secularization: monasteries became wealthy, involved in political life, and eventually were fully subordinated to ruling diocesan bishops. Over time, these bishops were chosen or appointed exclusively from among monks (sometimes not so much for their spiritual life as for their administrative and bureaucratic skills in church matters—finding compromises). Clergy increasingly sought ecclesiastical careers, church rewards, grand titles, and high positions.

A paradoxical situation arose where bishops began to resemble the Jewish high priests and elders (the direct crucifiers of Christ), monks resembled the Pharisees of the Gospel, and Christian theologians resembled the Talmudic scribes. Ritualism became accepted as the norm, and in city markets, harbor docks, and royal chambers, it became fashionable to discuss the mysteries of the person of Jesus Christ, the Holy Trinity, and other sacred matters.

Out of a desire to please the authorities, Christian theologians began to praise the existing Byzantine monarchy and its disgraceful and inhumane slave-owning system, despite the fact that 1 Samuel 8 directly describes monarchies as ungodly pagan inventions. Fanatical monarchists were not deterred even by the Gospel's clear disapproval of Herod (supposedly "God's anointed") and Pontius Pilate—the authorized representative of an even more powerful king (the Roman Emperor Tiberius).

At times, all Christians (even those living outside the Byzantine Empire) were pressured to defend the political interests of the Byzantine Emperor, in violation of Christ's commandment to respect (but not idolize) all earthly authority, but to refrain from engaging in political intrigues: “So when they met together, they asked him, ‘Lord, are you at this time going to restore the kingdom to Israel?’ He said to them, ‘It is not for you to know the times or dates the Father has set by his own authority. But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit comes on you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.’” (Acts 1:6–8).

Since the time of Constantine the Great, wars began between Christian peoples and kingdoms, and within the Christian empire itself, protests against social injustice and national oppression took on a distinctly anti-church (specifically, anti-Orthodox) character, as seen with the Copts, Armenians, Syriac Jacobites, and Donatists.

Related topics

Literature

- Friedländer, «Darstellungen aus der Sittengeschichte Roms» (6 изд., 1888, т. III);

- Aurich, «Das antike Mysterienwesen in seinem Einflusse auf das Ch ristentum» (1894);

- Wobbermin, «Religionsgeschichtliche Studien zur Frage der Beemflussung des Urchristentums durch das antike Mysterienwesen» (1896); Rohde, «Psyche» (1894);

- Wissowa, «Religion und Cultus der Römer» (1902);

- Boissier, «La religion Romaine» (1874);

- Réville, «La religion ŕ Rome sous les Sévè res» (1886);

- Zelinsky F. F., Melioransky B. M. Christianity // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Zelinsky, F. F., " Rome and its Religion "(Vestn. Europe", 1903, January-February). On ancient astrology: Bouche-Leclercq, " L'astrologie grecque "(1899);

- Zelinsky, F. F. " The Dead Science "(Vestn. Evr., 1901, Oct. - Nov.). About Palingenesia: Basiner, " The Legend of the Golden Age ("Russk. mysl', 1902, Nov.);

- Zelinsky, F. F. "The first end of the world" ("Vest. all. ist.", 1899, Nov.). Especially on the cult of the emperors, which later became the main cause of clashes between Christians and the Roman authorities (see below, section 6 (B)): Mommsen, Romische Geschichte (vol. V, 1885); Guiraud, Les assemblés provinciales dans l'empire Romain (1887);

- Ostapenko R. A. [The Christian mission of the Roman Empire among the Zikh people (the second half of the first — beginning of the fifth centuries AD)]. Pskov, 2016, pp. 86-98.

- Hirschfeld, " Zur Geschichte des romischen Kaisercultus "("Sitzungsberichte der Berliner Akademie", 1888, p. 833, sl.); Krasheninnikov, " Roman Municipal Priests and Priestesses "(1891); his, "Augustals and sacred Magistership" (1895).