Sertorian War

The Sertorian War, or Sertorius' War (Latin: Bellum Sertorium, 82–72 BCE), was a military conflict between the supporters of Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who had seized power in Rome, and the Marian faction led by Quintus Sertorius. The conflict took place in the territory of Roman Spain. During this civil war, several Spanish tribes sided with the Marians.

Quintus Sertorius

Quintus Sertorius (Latin: Quintus Sertorius; born in the 120s BCE—died in 73 BCE) was a Roman political figure and military commander, primarily known for leading a rebellion against the Sullan regime in Spain from 80 to 72 BCE.

Quintus Sertorius was born in the land of the Sabines, in the small town of Nursia on the Salarian Road, which was part of the Quirina tribe and is only occasionally mentioned in historical sources. It is known that the mother of Emperor Vespasian also hailed from this region. This territory was finally conquered by Rome in 290 BCE, and its inhabitants received Roman citizenship half a century later. The Sabines were reputed as a brave and warlike people, "native inhabitants of the country," whose settlers included the Samnites and Picentes. This tribe also produced notable figures in Roman history and culture of the 1st century BCE, such as Marcus Terentius Varro and Gaius Sallustius Crispus.

The exact date of Quintus Sertorius' birth is unknown. Historians suggest it was in the mid-120s BCE, approximately 123 or 122 BCE. The nomen "Sertorius" (Sertorius) is presumed to be of Etruscan origin. Plutarch describes this family as "prominent" in Nursia. It is likely that the Sertorii belonged to the municipal aristocracy and equestrian order, giving Quintus a good opportunity to build a successful career in his hometown. However, in Rome, he was considered a "new man."

Quintus Sertorius lost his father at an early age and was raised by his mother, "whom he seemed to love very much." His mother's name was Rhea; some researchers connect this name to the Sabine town of Reate. Sertorius received a good education, particularly studying law and rhetoric extensively. He had certain oratory skills; Cicero, in his treatise Brutus, refers to him as "the smartest and most articulate" among the "orators or, more accurately, shouters." This phrasing has led historians to conclude that, by Roman standards, Sertorius lacked professionalism. Nevertheless, he managed to gain "some influence" in Nursia during his early years through his speeches.

When Germanic tribes invaded the territories of the Roman Republic, Quintus Sertorius joined the active army. His first commander was Quintus Servilius Caepio, an influential patrician and renowned general who commanded the army in Narbonese Gaul in 106–105 BCE. It is believed that Sertorius served as contubernalis (a junior officer or companion) under Caepio and became his client. He might have used the patronage of this prominent aristocrat to advance in the new world of Roman politics.

In the Battle of Arausio on October 6, 105 BCE, Quintus Servilius' army was almost completely destroyed by the Germanic tribes. Sertorius was wounded and lost his horse in the battle but managed to escape by swimming across the river Rhodanus (Rhone), despite the strong current, and even saved his shield and armor. This episode from his life became a textbook example of military valor in Latin literature.

After this battle, Sertorius' hypothetical patron was condemned for his apparent responsibility in the defeat and suspicions of embezzlement. Command of the ongoing war against the Germanic tribes passed to Gaius Marius. Sertorius served under him, possibly from 104 BCE. During this period, Sertorius performed another remarkable feat: disguised as a Gaul, he infiltrated the enemy camp and gathered valuable intelligence, for which he was rewarded. It is suggested that this occurred on the eve of the Battle of Aquae Sextiae in 102 BCE. No further information is available about Sertorius' participation in the war against the Germanic tribes, which ended in 101 BCE.

Plutarch notes that Sertorius enjoyed Marius' trust, but the events of the 80s BCE suggest that good relations between these two "new men" were not established. A. Korolenkov suggests that Sertorius remained connected to the Servilii, enemies of Marius, who had lost most of his influence by the end of 100 BCE.

Military Campaign of 81 BC

Military Campaign of 81 BC

The next mention of Sertorius in historical sources is linked to Spain. In 98 BCE, he operated in this region as a military tribune under the consul Titus Didius. It is known that Didius defeated the Celtiberians, but Sertorius is mentioned only in connection with a military operation against the city of Castulo, located much further south in Iberia. The military tribune was part of the local garrison. When the residents of Castulo revolted and killed most of the Romans, Sertorius, along with a group of soldiers, managed to escape and then attacked the city in turn, killing all the men and selling the women and children into slavery. The same fate befell a neighboring city that participated in the uprising. For this, Sertorius received the highest military award—the corona graminea.

It is speculated that Sertorius joined Didius after these events, as it seems unlikely that such a brave and distinguished warrior would be stationed deep in the rear. Sertorius may have arrived in Spain as early as 99 BCE. Didius, also connected to the Servilii and the Quirina tribe, might have become his new patron. B. Katz suggested that Sertorius fought under Didius in Thrace, but there is no confirmation of this in the sources.

Upon his return to Rome, Sertorius secured election as quaestor. This magistracy was the first step in the cursus honorum and guaranteed a seat in the Senate. Exact dates are uncertain: Sertorius' quaestorship is placed in either 91 or 90 BCE. At that time, the Social War was beginning, and Sertorius was recruiting soldiers and preparing equipment for the army in Cisalpine Gaul. According to Plutarch, "he showed such zeal and speed in this task (especially when compared to the sluggishness and lethargy of other young commanders) that he gained a reputation as an energetic man." Later, Sertorius participated in combat and demonstrated extraordinary bravery; in one battle, he lost an eye, which he proudly regarded as a unique distinction. He became a celebrated war hero: Plutarch recounts that when Sertorius once appeared in the theater, "he was greeted with loud cheers." However, some believe that the biographer may have slightly exaggerated his hero's popularity.

Spain in the Early 1st Century BC

By the beginning of the 1st century BC, most of the Iberian Peninsula was part of the Roman Empire. In 197 BC, two provinces were established here: Nearer Spain, which included the lower and middle course of the Ebro River and the Mediterranean coast up to New Carthage, the administrative center; and Further Spain, which included Baetica, with Corduba as its principal city. Through nearly continuous warfare, by 133 BC, Roman holdings had significantly expanded into the central and western regions of the country, although many areas remained only nominally under Roman control. Scholars distinguish three zones based on the degree of Roman influence. Along the Mediterranean coast, the middle Ebro, and south of the Anas River, Roman power was strongest: most local communities were subjects, paid tribute, had no weapons of their own, and housed Roman garrisons; the inhabitants of the central part of the peninsula were vassals of the Republic, also paid tribute, and provided auxiliary troops; finally, there were the Vettones and Vaccaei in Celtiberia, as well as lands west and north of the Anas, which only nominally submitted to Rome. Sometimes Roman governors would take hostages from local communities or relocate tribes from the mountains to the plains, but generally, they aimed to maintain the status quo.

Lusitania, occupying the entire southwestern part of the Iberian Peninsula, was conquered by Decimus Junius Brutus in 138–137 BC, but this conquest was largely a formality. By the time of Sertorius' rebellion, the strong and numerous Lusitani people remained effectively independent of Rome. The Vascones on the far north continued to resist, as did the Astures and Cantabri, who did not submit to the Republic. The Romans had to regularly suppress uprisings in Nearer Celtiberia, repel Lusitani raids, and engage in skirmishes with the Vaccaei.

Communities in territories directly controlled by Roman governors held various statuses. The most privileged were cities that had signed special treaties with Rome and were considered free; these included some Phoenician and Greek colonies (Emporion, Malaca, Ebusus), the native city of Saguntum, and possibly a few other communities. These cities enjoyed full self-governance, paid no taxes, and were not required to host Roman garrisons. In times of war, their obligations were limited to moral support. Civitates stipendiariae were required to pay taxes to Rome, and their lands were considered ager provincialis, but these communities retained internal autonomy. Finally, there were the dediticii: communities that had surrendered unconditionally during wars and became mere subjects. They were under the complete authority of the provincial administration, and their status was not regulated by any laws.

Additionally, there were cities in Spain with Roman-style governance. These were primarily cities founded by Roman governors: Tarraco, Italica, Gracchuris. By the 80s BC, Italica likely had the status of a Latin colony, as did Ilerda, Carteia, and Corduba. There were no Roman colonies in Spain during the time of the Sertorian War, but there was active colonization by people from Rome and Italy: veterans who had completed their service, impoverished peasants, and businesspeople drawn by Spain's natural resources. By the early 1st century BC, in many cities, descendants of settlers had either displaced or fully assimilated the native populations. Most of these colonists were not Romans per se but Italians, primarily from Campania and possibly from Etruria.

Simultaneously, the local population was becoming increasingly Romanized. Spaniards were adopting the Latin language and Roman lifestyle, often serving in the Republic's army; some received Roman citizenship for their services, though this was still rare in the 80s BC. The success of Romanization is evidenced by the fact that many cities were minting coins with Latin inscriptions and beginning to take on a Roman appearance, with Latin schools emerging. Roman names became widespread. By the early 1st century BC, Romanization had made significant progress in the Ebro and Baetis basins and more modest progress in other regions. However, the primary achievement of Romanization, according to scholars, was that the native inhabitants of Spain no longer saw their future outside the Roman Empire and sought to emulate the Romans. This facilitated their active involvement in the Roman civil wars.

The Civil War

Quintus Sertorius departed for Spain in late 83 or early 82 BC, likely with only a small contingent; it is known that his quaestor was Lucius Hirtuleius, who would become his closest associate for the following years. Sertorius had to assert his authority over the province by force. According to Appian, "the previous governors did not want to accept him." Some historians infer from this that Nearer Spain was under the control of Sullan supporters, whom Sertorius defeated; according to another view, the proconsul only faced unrest among local tribes. Sertorius stabilized the situation by reducing taxes, abolishing the requirement for soldiers to lodge in cities, and establishing relations with the tribal nobility. According to Sallust, the Spaniards loved the governor "for his moderate and impeccable rule."

Despite this affection, Sertorius considered Roman and Italian colonists his primary support base. He armed all able-bodied men in this category, "kept a close watch" on the cities, and built a navy. The immediate goal of these actions was to maintain control over the Spaniards, but soon a new threat emerged. Sulla had secured a complete victory over the Marian forces in Italy, and his generals began to establish control over the western provinces. Sertorius' name was included in the first proscription list, meaning that his life was at stake, not just his career prospects. Sulla likely appointed Gaius Annius Luscus as the new governor of Nearer Spain, who marched across the Pyrenees in the spring of 81 BC. He commanded up to 20,000 soldiers, while Sertorius could field about 9,000 men; whether these included local tribesmen remains uncertain.

In the Pyrenees, Gaius Annius' path was blocked by a 6,000-strong Marian detachment under one of Sertorius' subordinates, Livius Salinator. However, Salinator was soon killed by a traitor, and his men abandoned their positions. Gaius Annius invaded the province, and Sertorius, unable to engage in battle, fled to New Carthage and there embarked his remaining troops on ships. Historians believe that his quick acceptance of defeat was not only due to the overwhelming numerical superiority of the Sullans. Sertorius was likely unpopular with his own soldiers (the abolition of winter quartering in cities might have contributed to this); moreover, the province's population, both Spanish and Roman-Italian, must have understood the futility of continued resistance given the Sullan victories throughout the Roman state. According to I. Gurin, the lack of support from the Celtiberians might have been a crucial factor.

For a time, the Sullans established control over all of Roman Spain. Sertorius crossed over to Mauretania but suffered losses in a skirmish with the local population, prompting him to return. The exiles likely landed near Malaca, where they were immediately defeated, but they received help from Cilician pirates at sea and managed to occupy the Pityusae islands. Soon after, Gaius Annius' fleet appeared. Sertorius engaged the enemy, but his light ships were ill-suited for the task. A mistral scattered them across the sea; only after 10 days was Sertorius able to land "with a few ships" on some islands. He then passed through the Strait of Gibraltar and landed again in Spain, near the mouth of the Baetis River. Researchers note that this was one of the most Romanized parts of the country, suggesting Sertorius might have chosen this landing site in the hope of receiving support from the local provincials. These hopes were not fulfilled, but the exiles managed to establish a long-term camp there, after which they returned to Mauretania.

A civil war was ongoing in Mauretania at the time, with the deposed Ascalis attempting to reclaim his throne. Sertorius intervened in the conflict, according to Plutarch, "hoping that his comrades, encouraged by new successes, would see them as a guarantee of future achievements and therefore would not disperse in despair." Historians infer from this passage that desertion was a very pressing issue at the time: the few supporters of Sertorius clearly considered the situation hopeless.

The exiles sided with the reigning king. Sertorius took command of this ruler's army and besieged Ascalis, who was supported by Cilician pirates, in Tingis. A detachment of Sullans from Further Spain under the command of Vibius Pacianus came to the aid of the besieged. Sertorius defeated this detachment and persuaded the enemy soldiers to join his side. According to Plutarch, after capturing Tingis, Mauretania came under Sertorius' full control, but the Greek writer likely exaggerates: Sertorius' forces were more likely in the position of military specialists and could not wield power over the entire kingdom.

Soon after this success, Lusitanian envoys arrived to invite Sertorius to become their leader. Plutarch writes that the Lusitanians made this offer "after learning of Sertorius' character from his companions." This may indicate that the initiative came from Quintus himself: he may have specifically sent his people to Spain to prepare the ground for his return. An alliance was formed. In connection with this, some scholars believe that Sertorius betrayed the Roman Republic or, at the very least,took a decisive step toward breaking with it. Others suggest that his actions were unconventional but not necessarily treacherous. Scholars note that the two sides of the alliance pursued completely different goals: the Lusitanians either needed military expertise or aimed to use Rome's internal conflicts to solidify their independence, while Sertorius intended to use the Lusitanians as a tool in the Roman civil war.

The Securing of the Marians in Spain

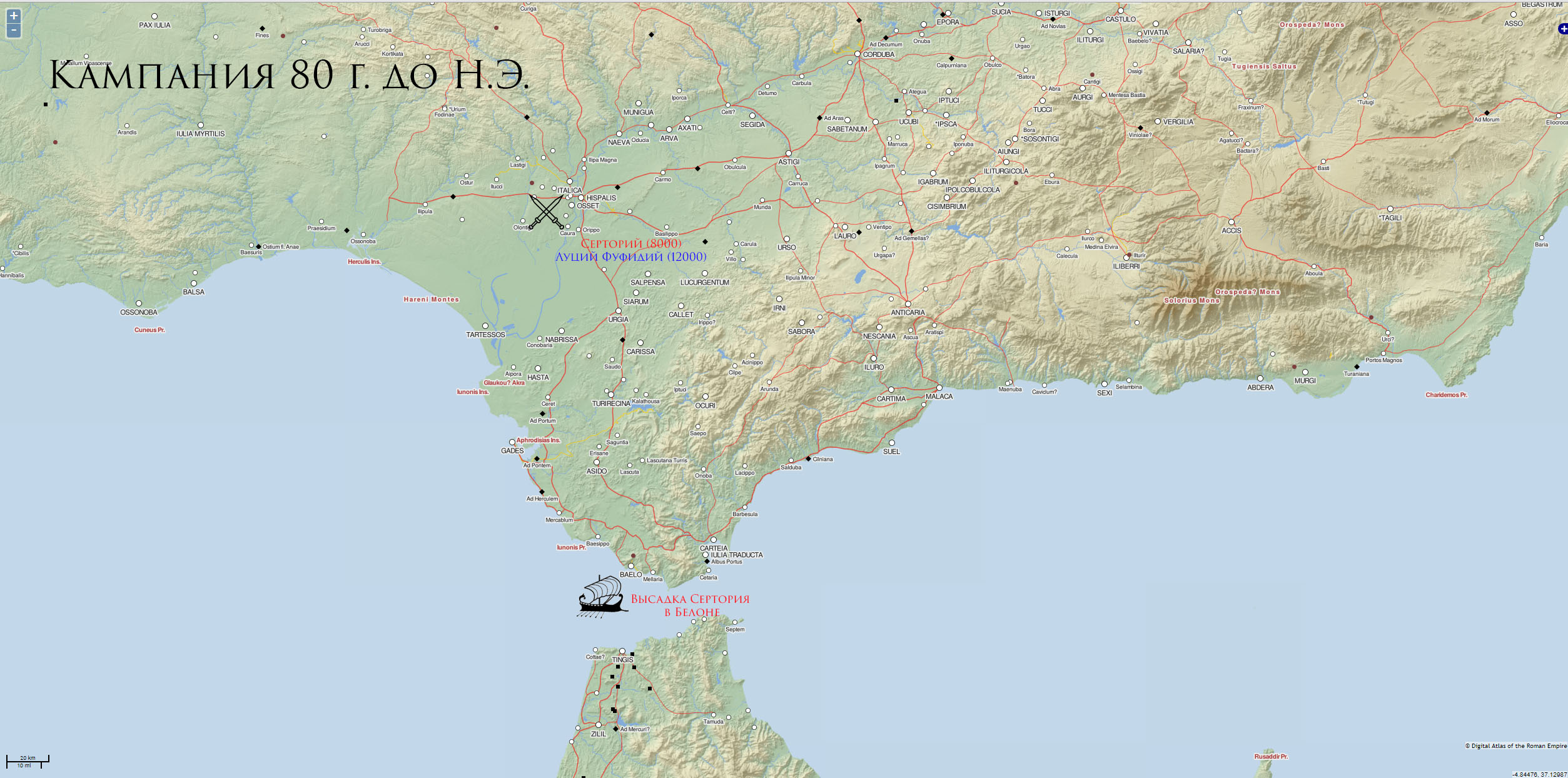

In 80 BC, Sertorius crossed from Tingis to Spain, landing near the city of Baelo with a contingent of 2,600 Romans and 700 Mauritanians. Some historians believe that just before this landing, he defeated a Sullan fleet under Cotta at Mellaria. According to another hypothesis, this victory occurred after Sertorius had already established himself in Spain.

At Baelo, Sertorius was met by more than 4,000 Lusitanians. According to Plutarch, the 8,000-strong rebel army faced "120,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, 2,000 archers, and slingers." However, this is likely an anachronism, as the Greek historian describes the situation in 74 BC. In 80 BC, the governor of Further Spain, Lucius Fufidius, might have had 15,000–20,000 soldiers, or perhaps only 10,000–12,000, and judging by the fact that he allowed a large Lusitanian force to reach Baelo, he did not fully control the situation in his own province. The governor of Nearer Spain, Marcus Domitius Calvinus, also had two legions.

The first major battle of this war took place near the Baetis River (presumably near Hispalis). Lucius Fufidius was defeated, with 2,000 Romans in his army alone killed. The course of subsequent events is unclear: some scholars believe that Sertorius withdrew to Lusitania (according to this version, he was heading there even before the battle), while others think he took control of part of Further Spain. I. Gurin and A. Korolenkov suggest that most of the province supported the rebellion, though this might have been more about submitting to the stronger power than active participation in the war.

The extent of support Sertorius received in Lusitania is also uncertain. Sources mention that only 20 "poleis" were on his side, which may refer to fortified points or simply individual communities. I. Gurin believes that these were cities in Baetica, not Lusitania. Plutarch attributes the title of "strategos autokrator" to Sertorius, but this is clearly an exaggeration; there is no evidence that Quintus had any authority in Lusitania beyond military command. The events of the Viriathic War show that the Lusitanians could not field more than 10,000 warriors even under great strain. Sertorius, moreover, was unable to instill discipline in the native part of his army, often having to gain obedience not by orders but through explanations. This is exemplified by the episode involving two horses, described by several ancient authors.

Immediately after his landing, Sertorius began employing various tricks to strengthen his authority among the local tribes. In particular, he claimed to communicate with the gods. A man named Span gave him a fawn, and as the white deer grew tame, Sertorius declared it a "divine gift of Diana" and claimed that the animal revealed secret things to him.

"If he received a secret message that the enemies had attacked a part of his country or incited a city to revolt, he pretended that the fawn had revealed it to him in a dream, instructing him to keep the troops ready for battle. Similarly, if he received news of a victory by one of his generals, he kept the messenger's arrival a secret, brought out the fawn adorned with garlands to signify good news, and ordered everyone to rejoice and make sacrifices to the gods, claiming that soon everyone would know of some fortunate event." — Plutarch, Sertorius, 11.

Several sources mention Sertorius's fawn. This choice of sacred animal may be related to the widespread cult of the deer on the Iberian Peninsula. Additionally, Sertorius himself may have become an object of worship as a hero from afar; historiography draws parallels with the cult of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus in the 200s BC. Through this, Sertorius was able to solidify his authority.

According to A. Schulten, after defeating Fufidius, the rebel army did not grow, remaining at around 8,000 men. F. Spann believes that Sertorius gradually increased his forces to 20,000 warriors. Thanks to this growth, he was able to defeat the governor of Nearer Spain, Marcus Domitius Calvinus. According to one version, in 79 BC, Sertorius's quaestor Lucius Hirtuleius, with an army likely composed of provincials, invaded Nearer Spain and defeated Calvinus with his two legions. According to another version, in 80 BC, Marcus Domitius himself moved south to aid Lucius Fufidius but was presumably killed in battle. In any case, the failures of the Sullan forces in Spain were serious enough to draw the attention of Sulla himself. He sent one of his principal supporters, his colleague in the consulship of 80 BC, a member of the influential family and a cousin of his wife — Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius — to the Iberian Peninsula.

Map of the Military Campaign of 80 BC.

Map of the Military Campaign of 80 BC.

Sertorius versus Metellus Pius

In 79 BC, the war entered a new, more intense phase. The Sullan regime concentrated significant forces in Spain under the command of the proconsul Metellus Pius, a very experienced general. Sources depict him as an older man, lazy, and inclined to "luxury and indulgence." However, he was only a few years older than Sertorius and was highly regarded by the latter. I. Gurin suggests that "the idea of Metellus’s old age and lethargy was a persistent notion held by Plutarch."

Under the command of Quintus Caecilius were possibly four legions and auxiliary forces. Plutarch, mentioning 128,000 soldiers concentrated against Sertorius, might have referred to the situation in 79 BC and included the forces of Metellus Pius and the governors of Further Spain and Narbonese Gaul. According to some scholars, there were at least 40,000 Sullan legionnaires in the two Spains alone, with auxiliary forces possibly even more numerous.

Reports on the course of military operations from 79–77 BC are fragmented. From these, we can confidently reconstruct only the general picture. Metellus's army significantly outnumbered the enemy, so Sertorius opted for guerrilla tactics. He avoided large battles, instead harassing the enemy with ambushes, disrupting their supplies, and attacking when Metellus's soldiers began setting up camp. If Metellus started besieging a city, Sertorius would strike at his lines of communication, sometimes mobilizing massive forces for a short time (Plutarch mentions up to 150,000 warriors). One known instance is when he laid siege to the besiegers.

Plutarch provides a description of the siege of the city of Lacobriga. Metellus unexpectedly attacked this city, thinking the main Sertorian forces were far away. He expected to force the besieged to surrender within two days by cutting off their water supply, so he only took provisions for five days. However, Sertorius managed to quickly deliver 2,000 water skins to Lacobriga, thwarting Metellus's plans. Metellus was then forced to send an entire legion to get provisions, which fell into an ambush and was completely destroyed. As a result, Metellus had to retreat with nothing.

A detailed reconstruction of the military actions was attempted by A. Schulten. In his view, Metellus sent his legate Lucius Thorius Balbus to Nearer Spain, but along the way, the latter was intercepted by Lucius Hirtuleius, suffered defeat at Consabura, and perished. Subsequently, Metellus operated in Lusitania between the Guadiana and Tagus rivers. In 79 BC, he moved from Baetica to central Lusitania, then to Olisipo. In 78 BC, he advanced west and southwest; it was likely during this time that the siege of Lacobriga occurred. Metellus devastated all the lands on his path, aiming to deprive the enemy of supply bases, but he was unable to effectively counter the guerrilla warfare, and by the end of 78 BC, he shifted to a defensive position in Turdetania.

Silver Denarius of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius. 81 BC.

Silver Denarius of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius. 81 BC.

Most scholars agree with this reconstruction. I. Gurin believes that the military actions during these years took place in Baetica, in the northeastern part of Further Spain, and in southern Lusitania, but not deep within the country. A. Korolenkov disagrees with this hypothesis, arguing that Baetica, unlike Lusitania, was not suited for guerrilla warfare.

In the struggle against Metellus, Sertorius, although avoiding defeat, lost much of his position in Baetica—according to A. Korolenkov, "without much resistance." This would have been considered a significant success for Metellus. However, Metellus's army was so weakened that it could not counter the rebels' advance in Nearer Spain. Here, after the defeat of Thorius Balbus in 78 BC, the Sullan governor of Narbonese Gaul, Lucius Manlius, arrived with three legions. Lucius Hirtuleius defeated him at Ilerda and forced him to flee with a small group back to his province. Sertorius then appeared in Nearer Spain. Plutarch claims that all tribes north of the Ebro submitted to him, but historians consider this an exaggeration, though they do acknowledge that during the campaign of 77 BC, a significant portion of the province, or even the majority, likely sided with the rebels. The key cities—New Carthage, Tarraco, and Gracchuris—apparently remained under Sullan control.

In 77 BC, Sertorius received reinforcements from Italy. In 78 BC, one of the consuls, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, led a rebellion to overthrow the Sullan regime, and after his defeat, he transferred his army to Sardinia, where he soon died. His successor in command, Marcus Perperna, continued the struggle. According to Orosius, Perperna crossed to Liguria, from where he threatened Italy but was pushed back towards the Pyrenees. Exuperantius reports that Perperna crossed directly from Sardinia to Spain. There, he intended to fight Metellus on his own, but his soldiers forced him to join Sertorius. According to Plutarch, this happened when it became clear that another Sullan army was moving towards Spain. According to Appian, the order of events was the reverse: the Senate sent another commander to Spain after learning of Sertorius's strengthening position.

Perperna commanded 53 cohorts, more than 20,000 soldiers—mostly Romans and Italians. Such substantial reinforcements reached Sertorius shortly before his capture of Contrebia, likely no later than September 77 BC.

Both Perperna and Sertorius were praetorians (former praetors). However, Perperna had a clear formal advantage as the son and grandson of consuls, so he could claim overall command; only the soldiers' demands forced him to submit to the "new man." There is a hypothesis that Sertorius had to engage in a fierce power struggle at this stage. It is to this period that Plutarch's story about Quintus receiving news of his mother's death and withdrawing from all affairs for seven days may relate; he might have been simply blackmailing his associates with a refusal to command to gain maximum authority. He emerged victorious from this struggle, but the heterogeneity of his entourage, which intensified due to Perperna's arrival, later played a negative role.

The Hispano-Roman State of Sertorius

By the autumn of 77 BC, Sertorius had reached the peak of his power. At that time, he controlled vast territories in Spain. These included Lusitania (fully or partially), the central part of the Iberian Peninsula, parts of Further Spain, the Mediterranean coast except for a few locations, the middle course of the Iber River, and territories north of this river up to the lands of the Vascones. This encompassed at least half of the entire territory of Spain. It is known that the Sullan forces maintained influence in Baetica (at least in its eastern part) and in most Roman and Phoenician cities. Nevertheless, Sertorius managed to create an extensive and powerful state that posed a serious threat to the Sullan regime.

Appian reports that, in addition to Spain, neighboring regions recognized Sertorius' authority. This could refer to part of Roman Gaul, where the inhabitants dealt a final defeat to Lucius Manlius in 78 BC, which many historians see as evidence of Sertorius’ influence in that region.

There may have been certain contacts between the rebels and the Roman political elite. Plutarch reports that "former consuls and other most influential persons" "called Sertorius to Italy, claiming that many there were ready to rise against the existing order and stage a coup." It is believed that it is impossible to verify the accuracy of this information: in Plutarch, only Perperna mentions these calls, attempting to delay his execution. In such a situation, he could have said anything. It is known that in Rome, the question of amnesty for Sertorius was never raised, meaning the influence of his hypothetical supporters was minimal. High-ranking individuals who had contact with Sertorius (including, for example, the consul of 73 BC, Gaius Cassius Longinus) apparently did not plan to support him.

Sertorius may have been popular among common Italians and Romans, but there was no movement in favor of Sertorius in Italy and Rome. However, some members of the Sullan elite feared that the rebellion might spread to Italy. Sallust included in his "History" a speech by Lucius Marcius Philippus, in which the orator frightened the Senate with the alliance between Sertorius and Lepidus. It is unclear whether such an alliance actually existed or if this was merely a rhetorical device. According to I. Gurin, Sertorius made a serious mistake by not focusing all his forces in 79–78 BC on capturing Nearer Spain and preparing for a campaign in Italy. The researcher believes that the rebels had a chance for victory at that time, which disappeared after Lepidus crossed over to Sardinia.

Regarding Sertorius' goals, scholars have no unified opinion. Different researchers argue that the rebellion was for him an attempt to simply survive, create an alternative state structure in Spain, or overthrow the Sullan regime on a larger scale within the Roman state. Sertorius' state is described as an "independent Spain," as a Hispano-Roman or Romano-Spanish state, or as an "anti-Rome" (Gegenrom).

In its internal structure, Sertorius' state had a dual character. On one hand, it was an alliance of Spanish communities (according to Yu. Tsirkin, it covered almost the entire non-Romanized part of Spain). Sertorius maintained control over this alliance partly as a military leader and partly as a patron of individual tribes, cities, and representatives of the local nobility. The Spaniards swore allegiance to him as their leader and joined his retinue. Representatives of individual communities gathered together to make decisions about recruiting warriors and distributing burdens. On the other hand, it was a Roman political structure, which Sertorius governed as a proconsul appointed by the Marian government. According to the political practice of that era, the term of proconsular authority ended only when its holder returned from the province to Rome. At the same time, the Sullans probably considered Sertorius' authority illegitimate from the moment he made an alliance with the Lusitanians. Sertorius did not allow native Spaniards into positions of power. As a proconsul, he granted Roman citizenship en masse to provincials who supported him with arms. This is indicated by the mention of "Sertorians" in several inscriptions found in various regions of Spain. It is likely that after the suppression of the rebellion, the citizenship of these people was not confirmed. For the children of the native nobility, Sertorius established a school modeled on Roman schools:

"He gathered in the large city of Osca the noble boys from different tribes and assigned teachers to them to acquaint them with the knowledge of the Greeks and Romans. In essence, he made them hostages, but in appearance—he educated them so that, when grown up, they could take on governance and power. And the fathers were extraordinarily happy when they saw their children in togas with purple borders marching in strict order to school, how Sertorius paid their teachers, how he gave rewards to the deserving, and bestowed golden necklaces, called 'bullae' by the Romans, on the best." — Plutarch, Sertorius, 14.

If this account is taken literally, it can be understood that the parents of the students received Roman citizenship, and the graduates of the school were supposed to be included in the equestrian order and thus gain the right to be elected to the highest offices of the Roman Republic. Many researchers see in this school only a way to obtain hostages. For H. Berve and F. Spanna, the togas and bullae were a deliberately unserious endeavor, a direct mystification that can be placed alongside Sertorius' tales of a hind. Yu. Tsirkin sees in this initiative of Sertorius both demagoguery and a desire to demonstrate to the local aristocracy its prospects in the event of victory and a desire to rely in the future on Romanized noble youth. For I. Gurin, the main point of this episode is the fixation of the Spanish nobility's claims to join the Roman ruling class.

There is an opinion that a principle of collegiality existed in the governance of Sertorian Spain. This is based on Cicero's words that Mithridates sent envoys to the generals with whom the Romans were fighting at that time, and on Perperna's complaints that the proconsul, at the end of the war, decided everything without consulting his circle (these complaints may indicate that Sertorius had consulted earlier). Livy reports that after Sertorius' death, the "Imperium partium" passed to Perperna, and Yu. Tsirkin suggests that this may refer not only to informal party leadership but also to some official status.

According to another hypothesis, the political system in Sertorian Spain is characterized as a mild dictatorship that operated with the consent of a consultative body and local officials. In creating the state apparatus, the proconsul resorted to appointments rather than elections, which could have been formally approved by a council. In particular, Sertorius appointed praetors and quaestors from among his senators, who were likely no fewer than six in number. Additionally, he appointed prefects and legates, who sometimes combined military functions with civil ones. For example, Marcus Marius, sent by Sertorius to Asia, acted as a governor of praetorian rank. This is confirmed by the fact that Marius was accompanied by lictors with fasces.

The consultative body that existed under Sertorius was probably officially called the Senate. Its creation is dated in historiography to 78 or 76 BC. A. Korolenkov suggests that the Senate could have appeared only after Perperna arrived in Spain, as before that, Sertorius' camp had almost no people of senatorial rank. Some scholars believe that with the creation of such a state organ, Sertorius wanted to emphasize the illegitimacy of the Sullan government. On the other hand, there are opinions that this measure was ineffective in such a context and destroyed the last chances for reconciliation. Another reason for creating the Senate might have been the search for a compromise with the representatives of the Roman nobility who arrived in Spain with the remnants of the Lepidian army. Besides Marcus Perperna, these included the patrician Lucius Cornelius Cinna, Lucius Fabius Hispanus, Manius Antonius, Gaius Herennius, Marcus Marius, and others. Since under the normal procedure for replenishing the Senate, it was unlikely to gather 300 members, Sertorius probably appointed senators himself.

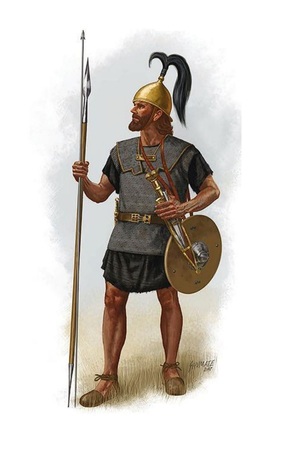

Legionaries from the so-called "Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus": Louvre, Paris. (Replica in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow). Late 2nd century BC.

Legionaries from the so-called "Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus": Louvre, Paris. (Replica in the Pushkin Museum, Moscow). Late 2nd century BC.

The real influence of the Senate appears to have been not very significant. The sources mention only one instance of its involvement in politics—the discussion of the terms of an alliance with Mithridates. The senators approved the conditions proposed by the king, but Sertorius later refused to accept one of them, the most important one—the cession of the province of Asia. From this, it follows that the final decision rested with the proconsul.

Sertorius' capital was Osca. Most researchers believe this to be the modern city of Huesca in Aragon. The Roman provincial division was maintained: according to one view, these were Nearer and Further Spain, according to another—Celtiberia and Lusitania with administrative centers in Osca and Ebora, respectively.

Sertorius' army was his most crucial support. The sources mention its size only twice: Plutarch states 150,000 warriors, and Orosius—60,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. In historiography, Orosius' data are generally accepted, albeit with some reservations: this writer refers to the time of the Battle of Lauro, and the size of the rebel army could not have remained the same throughout the war.

It is known that Sertorius' army was divided into cohorts. Legions are not mentioned, but they may have existed. The issue of the ethnic composition of the army probably cannot be resolved with the current state of the sources. In the early years of the war (79–78 BC, when the Sullan forces were led by Metellus Pius), Lusitanians primarily fought for Sertorius. Later (in 77–76 BC), at least 20,000 Romans and Italians who came with Perperna joined his army, as well as many Celtiberians. Simultaneously, there was an influx of emigrants from Italy. By the end of the war, this influx had almost stopped, and Sertorius was driven out of most Romanized regions, so the proportion of Spaniards must have increased.

According to Plutarch, command positions in the rebel army were held only by Romans. Scholars assume that native units were still led by tribal chiefs. Sertorius introduced "Roman equipment, military formations, signals, and commands" throughout his army. There is no consensus on its combat effectiveness: some historians highly rate the fighting qualities of the Sertorians, while others believe that the rebels were inherently inferior to Metellus and Pompey's soldiers and were only suitable for guerrilla warfare. The proconsul's attempts to instill some discipline in the native units are illustrated by a story told by Plutarch about two horses:

"Sertorius called a public assembly and ordered two horses to be brought out: one completely exhausted and old, the other a stately, powerful one, and most importantly, with an amazingly thick and beautiful tail. The feeble horse was led by a man of enormous size and strength, while the powerful one was led by a small and miserable man. As soon as the signal was given, the strong man grabbed his horse's tail with both hands and tried to pull it out, while the feeble man, meanwhile, began to pull out the hairs of the powerful horse's tail one by one. The great efforts of the first were fruitless, and he gave up his task, causing only laughter from the spectators, while the feeble competitor soon and without much effort plucked the tail of his horse. Then Sertorius rose and said, 'You see, comrades, perseverance is more useful than strength, and much that cannot be accomplished in one stroke can be achieved if acted upon gradually. Constant pressure is irresistible: with its help, time breaks and destroys any force, it becomes a benevolent ally of a man who knows how to choose his time wisely, and a desperate enemy to all who hasten events untimely.'" — Plutarch, Sertorius, 16.

In any case, as is known, Sertorius was unable to deliver a decisive defeat to the government forces.

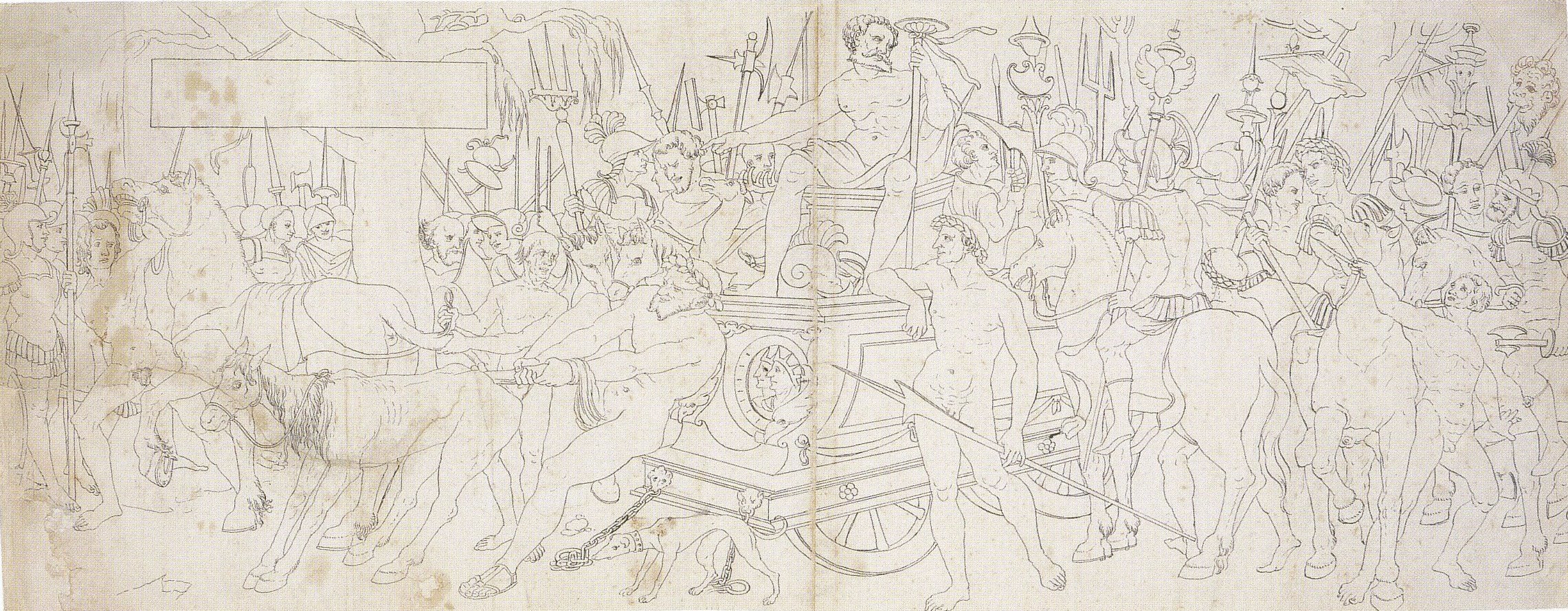

Hans Holbein the Younger: Episode with Two Horses. 1515–1532 AD.

Hans Holbein the Younger: Episode with Two Horses. 1515–1532 AD.

The Campaigns of the Marian Faction against Metellus Pius and Pompey

The campaign of 77 BCE brought the Roman government to the brink of complete defeat at the hands of Quintus Sertorius, even threatening a potential invasion of Italy. In response, the Senate sent another general, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great), to Spain, granting him proconsular authority despite his youth and lack of experience in high office. Pompey crossed the Pyrenees either at the end of 77 or the beginning of 76 BCE. At the start of the new campaign, the Indigetes and Lacetani tribes sided with him, and around the same time, Pompey's quaestor Gaius Memmius landed in New Carthage.

Pompey advanced south along the Mediterranean coast. At this time, Sertorius was besieging Lauron, which had recently defected to the Roman government, and Pompey deemed it necessary to assist the city. According to Orosius, Pompey commanded 30,000 legionaries and 1,000 cavalry, along with numerous auxiliary troops. The two armies faced each other near Lauron, and eventually, a battle ensued. Sertorius had set a trap for Pompey’s foragers, and when Pompey sent a legion to rescue them, it too was surrounded. When Pompey brought out his main forces, Sertorius revealed his heavy infantry on the hills, ready to strike from the rear. Consequently, Pompey abandoned the idea of a full-scale battle and accepted the loss of 10,000 soldiers. Soon after, the Sertorians stormed and captured Lauron.

Following this defeat, Pompey retreated towards the Pyrenees, his reputation severely damaged. People remarked that he had been close enough to feel the heat of the flames engulfing the allied city but did nothing to save it. For the remainder of the campaign, Pompey remained inactive, and some communities that had initially sided with him might have switched their allegiance back to Sertorius. Meanwhile, Sertorius had success in Celtiberia, capturing several towns.

The following year, 75 BCE, was decisive. Sertorius' strategy was for Perperna and Herennius to hold off Pompey in the northeast, while Lucius Hirtuleius would defend southern allies against Metellus, avoiding major battles. Sertorius himself planned to campaign against the Berones and Autrigones in the upper Ebro valley. This plan is often characterized as cautious and reflects an underestimation of Pompey.

Sertorius did move into the upper Ebro valley in the spring. The beginning of this campaign was successful, but meanwhile, Pompey crossed the Ebro, reached Valentia, and defeated Herennius and Perperna. Ten thousand rebels, including Herennius, were killed, and Valentia was captured and destroyed. This serious defeat forced Sertorius to return to the coast to confront Pompey. He likely joined forces with the remnants of Perperna's troops before the battle.

Pompey, emboldened by his victory, also sought a major battle. According to Plutarch, he was eager to engage Sertorius before Metellus could arrive, so as not to share the glory. The two armies met at the river Sucro. Sertorius commanded the right wing. Pompey, also leading his army's right flank, managed to push back the enemy on his side until Sertorius arrived and routed his troops. Pompey was wounded and only escaped because his Libyan pursuers were distracted by his richly adorned horse. Meanwhile, Pompey's left flank, led by Lucius Afranius, briefly gained the upper hand and even broke into the enemy camp. However, Sertorius' arrival turned the tide against the Pompeians once more.

The Ebro River (in ancient times — Iber) in the lower reaches. Anti-Sertorian sources portray this battle as if the outcome was a draw. Nevertheless, Pompey's defeat was obvious. Sertorius couldn't destroy his army just because it took refuge in the camp. The next day, it was discovered that Metellus was approaching, so Sertorius retreated. According to Plutarch, he said: "If it wasn't for that old woman, I would have whipped that boy and sent him to Rome."

Metellus, on the eve of the march to Sucron, defeated Hirtuleius at Italica. The Quaestor Sertorius accepted the battle despite the commander's express prohibition; some historians believe that he did so to prevent the combined forces of Metellus and Pompey. Girtulei's soldiers spent several hours in the heat, challenging the enemy to battle. Metellus, who placed the strongest formations on the flanks, was able to surround the enemy and inflict a complete defeat on him. Twenty thousand Sertorians were killed, including Lucius Hirtuleius himself.

As a result of these events, Sertorius was left with only one army out of three, forced to confront both Pompey and Metellus. He had to abandon all hopes of finishing off Pompey and leave the Mediterranean coast. It was a complete strategic defeat.

Now the military operations were transferred to the central part of the Iberian Peninsula — to Celtiberia. Sertorius was forced to retreat to the Arevacian lands of Segontia, while Metellus and Pompey joined forces. Presumably it was then that Sertorius proposed reconciliation. He expressed his readiness to "lay down his arms and live as a private citizen, if only he gets the right to return," but his offer was not accepted. On the contrary, Metellus announced a bounty on his head of 100 talents of silver and 20 thousand jugers of land, and the exile-the right to return to Rome.

Sertorius was able to lock the enemy in a valley near Segontia with a series of maneuvers and make them feel an acute shortage of food. Despite the benefits of his position, he was forced to fight — perhaps because his warriors insisted on it. Sertorius himself took part in the battle, attacking Pompey's army; in this direction the rebels were victorious, and among the 6 thousand dead Pompeians was the Quaestor Gaius Memmius. At the same time, the army of Perperna suffered heavy losses in the battle with Metellus (5 thousand killed). From Appian's account, it follows that here the government forces gained the upper hand. Sertorius came to the aid of his legate :" he pressed the enemy and fought his way to Metellus himself, sweeping away those who still held on." Metellus was wounded, but his soldiers still forced the enemy to retreat.

The Sertorians retreated to the mountain fortress of Clunia. The Senatorial armies besieged them there, but Sertorius was able to break through and began a guerrilla war. In the end, Metellus retired to Narbonne Gaul for winter quarters, and Pompey wintered in the lands of the Vaccaeans after a series of maneuvers in Vasconia. At that time, both sides were on the verge of exhaustion; Pompey demanded reinforcements and money from the Senate, saying that otherwise Italy would be the theater of military operations. For the Roman government, the situation was worsened by the need to fight also in Thrace and Isauria. But in the following years, Pompey and Metellus received the necessary reinforcements, which ensured their victory.

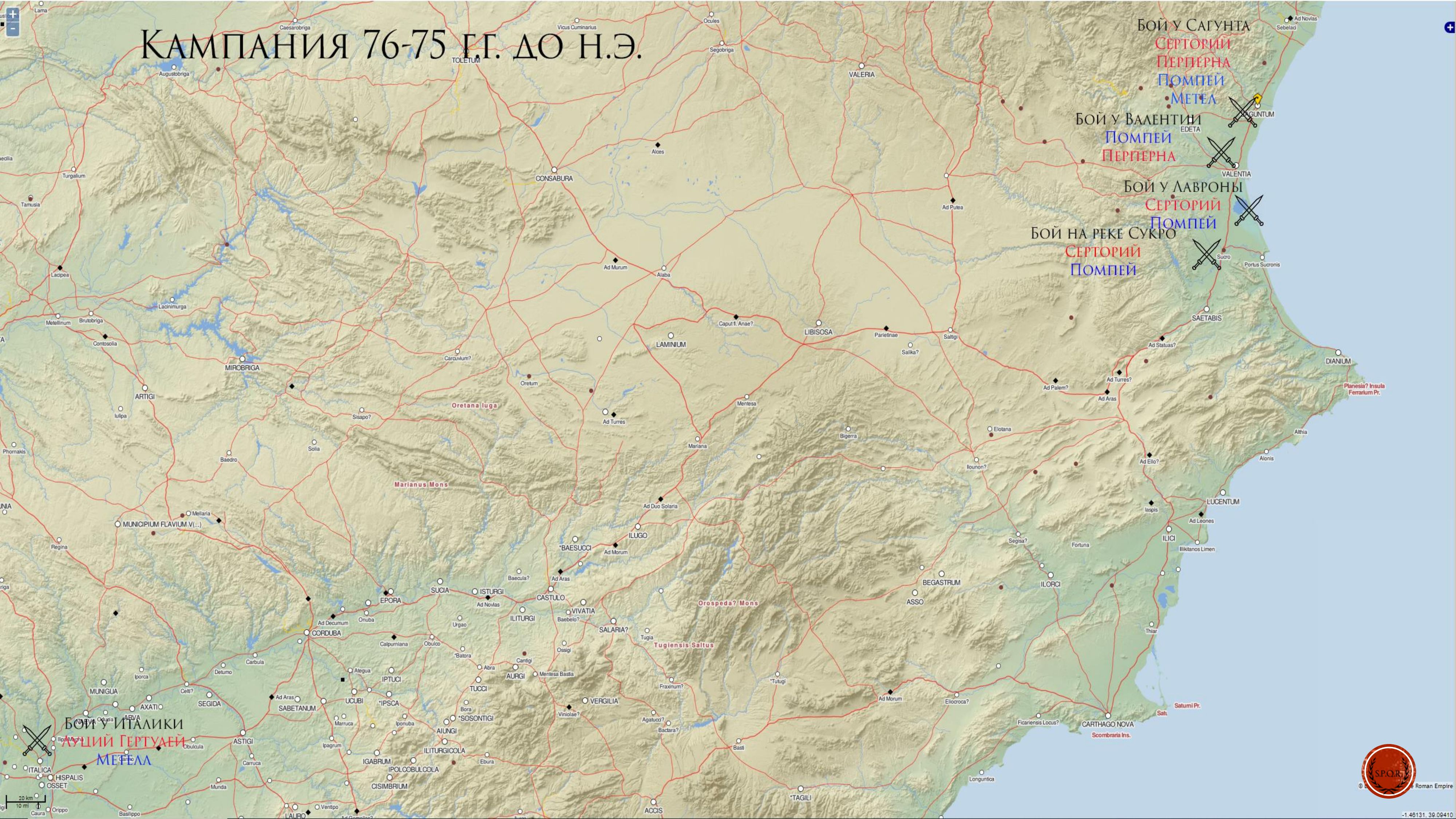

Course of the Campaign in 76–75 BC.

Course of the Campaign in 76–75 BC.

Negotiations with Mithridates

Sources indicate that Sertorius engaged in negotiations with one of Rome’s most formidable enemies—King Mithridates VI of Pontus. At that time, Mithridates was finishing preparations for another, the third, war with Rome and was in need of allies. The initiators of these negotiations were Lucius Magius and Lucius Fannius, officers of Fimbria’s army who were present at the king’s court. They convinced Mithridates of the advisability of such an alliance, citing Sertorius’ military successes and the strength of his army. It is likely that they also traveled to Spain “with letters addressed to Sertorius and with proposals that they were to convey to him verbally.”

The exact dates of this mission are not recorded. In one of his speeches against Gaius Verres, Cicero mentions that in 79 BC, Magius and Fannius purchased a myoparon (a type of small warship) "on which they sailed to all the enemies of the Roman people from Dianium to Sinope." Since Dianium was a naval base of Sertorius, some researchers conclude from these words that as early as 79 BC, the Marian proconsul of Spain had formed an alliance with the King of Pontus. According to another perspective, the date of the ship's purchase is not very informative, and in 79 BC, Mithridates was still trying to strengthen peace with Rome. The conclusion of the alliance is thus dated to 75 BC, making it unlikely that the negotiations spanned four years.

Mithridates’ proposal was discussed in a meeting of the Senate. The king laid claim to Galatia, Paphlagonia, Cappadocia, Bithynia, and the Roman province of Asia. Most of the senators agreed to these terms. According to Plutarch, Sertorius rejected the main demand regarding Asia; according to Appian, he conceded this province to the king. Most scholars lean towards Plutarch’s version, with G. Berve being one exception. Mithridates was to provide 40 ships and 3,000 talents of silver, while Sertorius sent an expeditionary force to the East under the command of Marcus Marius, who became the Marian governor of Asia. The alliance was formalized in a written agreement. Some ancient authors claim that it was after concluding the alliance with Sertorius that Mithridates felt emboldened to start a new war against Rome, though this might be an exaggeration.

Scholars are divided on whether Sertorius received any substantial support from Pontus. There is a hypothesis that from the middle of 74 BC, the proconsul’s army was paid solely with the money sent by Mithridates. Sertorius may have hoped that Mithridates’ actions would force the Roman government to divert some troops from Spain to the East, but this did not happen.

The Death of Sertorius

As a result of defeats in the 75 BC campaign, the position of Sertorius and his supporters significantly deteriorated. They lost control over the Mediterranean coast, much of Nearer Celtiberia, and the lands of the Vaccaei, and were finally driven out of Further Spain. A substantial portion of the rebel forces was killed in the battles. Many tribes switched to the side of the government forces. Sertorius felt compelled to resort to repressions: he devastated the fields of traitors, executed or sold into slavery the students of the noble school in Osca. His relations with his Roman entourage also worsened, with many of them feeling unfairly sidelined from power. The epitomator of Livy mentions "many cruelties of Sertorius against his own people: he executed many of his friends and fellow exiles on false charges of treason." Defectors began to appear, and they were received rather leniently in the senatorial armies.

At this point, Spaniards clearly outnumbered Romans and Italians in Sertorius’ army. According to A. Korolenkov, this "changed the face of the uprising." Nevertheless, Sertorius continued to enjoy great authority in the eyes of most of his soldiers and could, for a time, ignore the discontent of his senior officers.

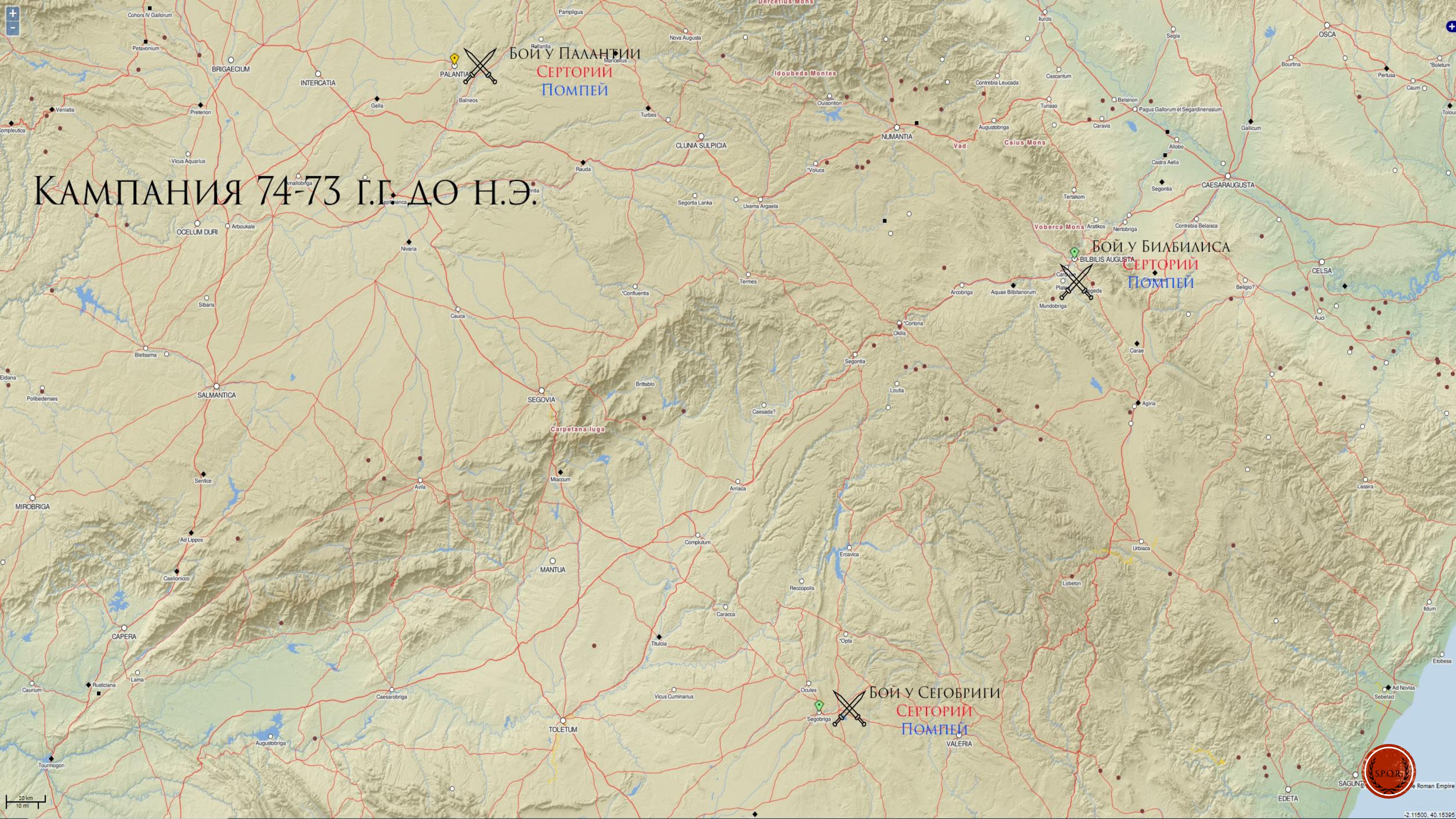

Course of the Campaign in 74–73 BC.

Course of the Campaign in 74–73 BC.

In the theater of military operations in 74–73 BC, the situation remained fairly stable. In 74 BC, Sertorius and Metellus engaged in battles with inconclusive outcomes near Bilbilis and Segobriga. Pompey attempted to take Pallantia but was repelled by Sertorius, who achieved a tactical victory at Calagurris, destroying 3,000 enemy soldiers. Overall, the government forces seem to have expanded their control in Nearer Celtiberia. Concerning the events of 73 BC, it is only known that Metellus and Pompey captured several towns previously under Sertorius' control; some of these surrendered without a fight. Some scholars infer from this that the senatorial forces took control of all of Further Celtiberia.

Meanwhile, Sertorius’ close associates conspired against him. Sources offer two different versions of events. According to Diodorus and Appian, Sertorius began acting like a tyrant: he disregarded his Roman comrades, oppressed the Spaniards, indulged in pleasures and luxury, and neglected affairs, which led to defeats. Seeing his cruelty and distrustfulness, and fearing for their lives, Perperna organized a conspiracy that was uncovered; almost all the conspirators were executed, but Perperna somehow survived and carried out the plot.

According to Plutarch, the blame lies entirely with Perperna. This commander, proud of his noble birth, "nurtured an empty ambition for supreme power" and thus began persuading other senior officers to revolt against their leader. He argued that the Senate had become a laughingstock and that the Romans had turned into "the retinue of the fugitive Sertorius," upon whom "insults, orders, and burdens are imposed as if they were some Spaniards and Lusitanians." During the preparations for the assassination, Perperna learned that news of the conspiracy was spreading uncontrollably and decided to act decisively.

In historiography, these two versions are considered complementary rather than mutually exclusive. The conspirators might indeed have had grievances about Sertorius' leadership style in his final years. At the same time, Perperna could have exaggerated his commander's tyranny to stir up agitation; Perperna’s ambition is seen as the main reason for Sertorius' death. Plutarch claims that the conspirators gained courage from their victories over the senatorial forces. However, it could have been the other way around—the defeats might have undermined the proconsul’s authority. There is a hypothesis that the conspirators opposed guerrilla warfare and wanted to confront the enemy in a decisive battle, which Sertorius had avoided.

Some scholars link the conspiracy to attempts to negotiate with the regime ruling in Rome. Some believe that the conspirators wanted to secure peace at the cost of Sertorius’ head; others think that Sertorius himself sought a compromise, which his entourage opposed. However, both versions lack support in the sources. Moreover, Metellus and Pompey demonstrated an unwillingness to negotiate even when the rebels' situation was much better.

Plutarch provides a detailed account of Sertorius' death. He reports that the conspirators sent a messenger with news of a great rebel victory. Perperna organized a banquet on this occasion and invited Sertorius. Although Sertorius was pleased by the news, he only agreed to come "after much insistence." Among the other guests at the banquet were Manius Antonius, Lucius Fabius of Spain, Tarquitius, the secretaries Maecenas, and Vercius.

As the drinking reached its peak, the guests, looking for an excuse to start a confrontation, began to speak freely, pretending to be very drunk, and made obscene remarks, hoping to provoke Sertorius. However, Sertorius—either displeased by the disorder or sensing from their bold words and unusual disregard for him the conspirators' intentions—merely turned on his couch and lay on his back, trying to ignore and not hear anything. Then Perperna raised a cup of unmixed wine and, after sipping, dropped it with a clatter. This was the signal, and immediately Antonius, who was reclining next to Sertorius, struck him with a sword. Sertorius turned towards him and tried to stand, but Antonius threw himself onto Sertorius' chest and grabbed his hands; unable to resist, Sertorius died under the blows of numerous conspirators.

— Plutarch, Sertorius, 26.

Command passed to Perperna. According to Appian, the head of the conspiracy was named in Sertorius' will as his successor. Perperna managed, albeit with some difficulty, to quell the soldiers’ discontent, but the Spanish tribes began to side with Metellus and Pompey, apparently considering themselves clients only of Sertorius, not his successor. In the first battle with Pompey, Perperna suffered a complete defeat, was captured, and was immediately executed. Most of Sertorius' followers received a pardon.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Gaius Marius

Literature

Ancient authors:

- Lucius Annaeus Flor. Small Roman Historians, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 1996, pp. 99-190. — ISBN 5-86218-125-3.

- Appian. Roman History, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 2002, 880 p. ISBN 5-86218-174-1.

- Valery Maxim. Memorable acts and sayings. - St. Petersburg: SPbU Publishing House, 2007. - 308 p. - ISBN 978-5-288-04267-6.

- Vellei Paterkul. Roman History // Small Roman Historians, Moscow: Ladomir, 1996, pp. 11-98. ISBN 5-86218-125-3.

- Aulus Gellius. Attic nights. Books 1-10. - St. Petersburg: Publishing Center "Humanitarian Academy", 2007. - 480 p. - ISBN 978-5-93762-027-9.

- Diodorus of Sicily. Historical library. The "Symposium" website.

- Dion Cassius. Roman history. Accessed January 6, 2016.

- Titus Livy. Istoriya Rima ot osnovaniya goroda [History of Rome from the foundation of the city], Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1994, vol. 3, 768 p.ISBN 5-02-008995-8.

- Letters of Pliny the Younger, Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1982, 408 p.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural history.

- Plutarch. Comparative biographies. St. Petersburg: Nauka Publ., 1994, vol. 3, 672 p. ISBN 5-306-00240-4.

- Gaius Sallust Crispus. History. Ancient Rome website.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. Life of the Twelve Caesars // Suetonius. The Lords of Rome, Moscow: Ladomir, 1999, pp. 12-281. ISBN 5-86218-365-5.

- Strabo. Geografiya, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 1994, 944 p.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero. Brutus // Three Treatises on Public Speaking, Moscow: Ladomir, 1994, pp. 253-328, ISBN 5-86218-097-8.

Contemporary authors:

- Gurin I. Sertorian war (82-71). Samara: Samara University, 2001. 320 p. ISBN 5-86465-208-3.

- Yegorov A. Julius Caesar. Political biography. Saint Petersburg: Nestor-Istoriya Publ., 2014, 548 p. ISBN 978-5-4469-0389-4.

- Korolenkov A. Quintus Sertorius. Political biography. - St. Petersburg: Alethea, 2003. - 310 p. - ISBN 5-89329-589-7.

- Korolenkov A. Mithridates and Sertorius / / Studia Historica, 2011, no. XI, pp. 140-158.

- Korolenkov A., Smykov E. Sulla. - Moscow: Molodaya gvardiya, 2007. - 430 p. - ISBN 978-5-235-02967-5.