Electoral Process in Ancient Rome

The earliest known elections to modern people took place in Ancient Greece, in the region of Attica, around the 11th-9th centuries BC. Elections were an integral procedure in the ancient Greek polis, with all free men participating. However, the outcome largely depended on the opinion of the aristocracy rather than the actual election results. The election results gained legal force during Pericles’ time, in the Golden Age of Athens. The Roman Republic adopted the principle of elections from the Greeks and improved upon it; this procedure was later used during the Roman Empire period and even later in the Eastern Roman Empire for elections to lower offices.

At the beginning of the establishment of the Roman Republic, according to the principle of “client-patron,” a client could vote for his patron in elections or campaign for others to vote for his patron in exchange for protection and assistance. However, later the Roman Senate legally introduced the principle of secret voting in the elections of magistrates (civil and military officials elected for short-term periods), and later also in cases concerning state treason. This principle complicated the possibility of unlawful accession to power, nullifying control over voters’ choices. According to leges de ambitu, to maintain healthy competition, candidates were prohibited from bribing voters by hosting free games, distributing money, and bread. Any candidate who violated these rules faced severe punishment. As in modern times, candidate registration and the election campaign began long before the voting day. A person who wished to run for a particular office had to notify the relevant magistrate in advance. The magistrate, in turn, had to check the candidate’s compliance with electoral laws and either include them in the voting list or deny their candidacy.

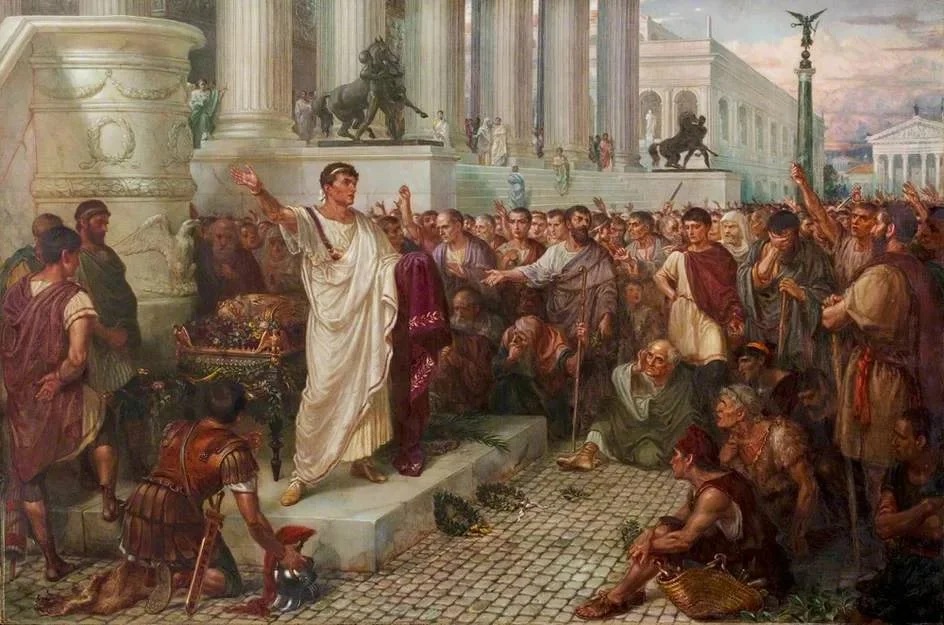

Julius Caesar by Pelagio Palaggio

Julius Caesar by Pelagio Palaggio

The day of candidate registration was considered the beginning of the election campaign, which lasted until the voting day. To emphasize their status and stand out from the crowd, candidates donned white togas—a symbol of a clear conscience. The leges de ambitu allowed candidates to address the public in markets and forums—the main squares of Roman cities. In meetings with the electorate, candidates behaved courteously, addressing each voter by name and seeking support for their candidacy. Each candidate had a slave, a nomenclator, whose duty was to remember each voter’s name and remind the candidate if the name was forgotten. Traditionally, on voting day, before the meeting of the comitia (a type of public assembly in Ancient Rome), the senior magistrates determined the will of the gods by observing the flight and cries of birds, a ritual known as auspicia—auspices. An augur oversaw the correct performance of the ritual and decided whether the gods favored the elections or not. If the augur observed bad omens, the elections were postponed, and the comitia was dismissed; if the omens were good, the meeting of the comitia began. Meetings could only take place during the day; any unfinished meetings after dark were postponed to another day. After the auspices were performed, the magistrates ordered the electorate to be convened and divided them into centuries (according to property census) or tribes (according to electoral district). The order of voting was determined by drawing lots—a wooden or bronze tablet inscribed with letters or verses. The tablets were placed in a special urn and mixed, and children or outsiders were entrusted with drawing one of them. The century that voted first was called the centuria praerogativa. The results of its voting were perceived by all other centuries as the will of the gods, which had to be followed. Currently, two types of voting are known: open, which existed before the establishment of the secret ballot principle, and directly secret. In open voting, the residents of Rome were directly asked if they were ready to support a particular candidate, and officials recorded all the votes “for” and “against.” In such a situation, patricians could easily influence the voters’ choice, which they actively exploited.

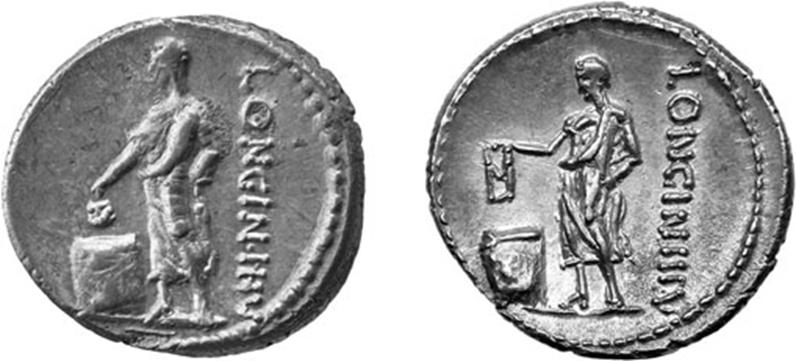

A coin depicting a voting citizen

A coin depicting a voting citizen

During secret voting, voters initially cast their votes using a sort of labyrinth, or as the Romans called it, saepta—a network of wooden partitions arranged in such a way that the voter could not exit on their own. This structure eliminated the possibility of repeated votes. Later, under Julius Caesar, marble columns were erected in place of the dilapidated wooden labyrinth. The labyrinth had many entrances, where voters waited for their turn. Voting began after a signal, with all centuries participating except the centuria praerogativa. The exact order of voting is unknown, but it is presumed that before entering the enclosure, voters received a tablet on which they wrote, or asked a trusted person to write, the names of their two candidates, then threw the tablets into an urn, and remained inside the labyrinth until the end of voting. Elections were held not only in Rome itself but also in all cities of the empire. Typically, in Roman provincial cities, the administration consisted of duumvirs—the highest officials, and decurions—members of the local senate. The quinquennals, elected every five years, compiled lists of citizens indicating property census and formed the senate. Everyday city duties (public works, grain supply, street cleaning, etc.) were assigned to junior magistrates—aediles. Elections to local government bodies were conducted by dividing each city into several curiae—electoral districts.

All adult and free citizens could run for ordinary offices, but the requirements for candidates for higher provincial magistracies were stricter: in addition to being an adult and a citizen, they needed an unblemished reputation, possession of certain property, and a gradual progression through the ranks. Only former aediles could become candidates for duumvirs. The names of candidates were announced in advance by a duumvir or quinquennal conducting the elections. In the case of an insufficient number of candidates, they were allowed to choose deputies, who in turn could choose assistants, and all these people ended up on the electoral lists. As in elections in the capital, in the provinces, voters wrote the name of their candidate on a tablet and threw it into an urn. Not only individual candidates but also city societies, such as youth unions, rural unions, or urban associations, could participate in the elections. Women also participated in the election campaign. The election procedure took place in March. The outcome of the elections in the provinces was determined differently from that in the capital. First, the voting results were summed up in each curia separately, then the results from all curiae were compared, and the candidate who received the majority of votes from the curiae won. The newly elected officials assumed office on July 1st and served for a year.

During the election campaign, walls of houses covered with white plaster were painted with red campaign inscriptions. The candidate's name was written in large letters at the top, followed by a call to the voter, and below that, the names of deputies were written in smaller print. The inscriptions remained throughout the term of the elected officials and were covered with a new layer of plaster during the next election campaign. The content of the campaign inscriptions varied. Some described the candidates’ high moral qualities, professional achievements, or noble origins. Less frequently, obligations or programs of the candidates were mentioned. Archaeologists have also found inscriptions containing slander about the candidates or caricatures of them, with some such inscriptions showing attempts by the candidate’s supporters to erase negative remarks. Additionally, neutral inscriptions were found, simply urging people to vote. For example, the following inscriptions can be cited: “Neighbors, wake up and vote for Ampliatus. May you fall ill if you erase this out of envy!” “I ask you, Loreius, to elect Ceius Secundus as duumvir, and he will choose you in return” “If an honest life benefits people, then Lucretius Fronto is fully worthy of honor.”

Campaign bowls. These were filled with food and distributed on the street before the elections to the poor. The inscriptions inside the bowls contained calls to vote for a particular candidate. Left—a bowl urging a vote for Cato the Younger in the elections of the tribunes of the people (63 BC); right—for Catiline in the consular elections (66 BC).

Campaign bowls. These were filled with food and distributed on the street before the elections to the poor. The inscriptions inside the bowls contained calls to vote for a particular candidate. Left—a bowl urging a vote for Cato the Younger in the elections of the tribunes of the people (63 BC); right—for Catiline in the consular elections (66 BC).

Related Topics

Augur, Roman Empire, Roman Republic

Literature

- Beard M. SPQR: A History of Ancient Rome/ Mary Beard; Trans. from English. – 2nd ed.- M.: Alpina non-fiction, 2018.-696 p.

- Vedeneev Y.A., I.V. Zaitsev, V.E. Korablin, V.V. Lugovoy, V.V. Tylkin. — Kaluga: Kaluga Regional Foundation for the Revival of Historical, Cultural, and Spiritual Traditions "Symbol", 2002. — 692 p.: ill.

- Giro P. Private and Public Life of the Romans/ SPb, "Aleteya", 1995.-582 p.

- Kuzishin V.I. History of Ancient Greece.// Edited by V.I. Kuzishin. M.: Higher School, 1996.-377 p.

- Sergienko M. E. The Life of Ancient Rome. / SPb.: Publishing and Trading House "Summer Garden"; Journal "Neva", 2000. — 368 p.