Reign of the Flavian Dynasty

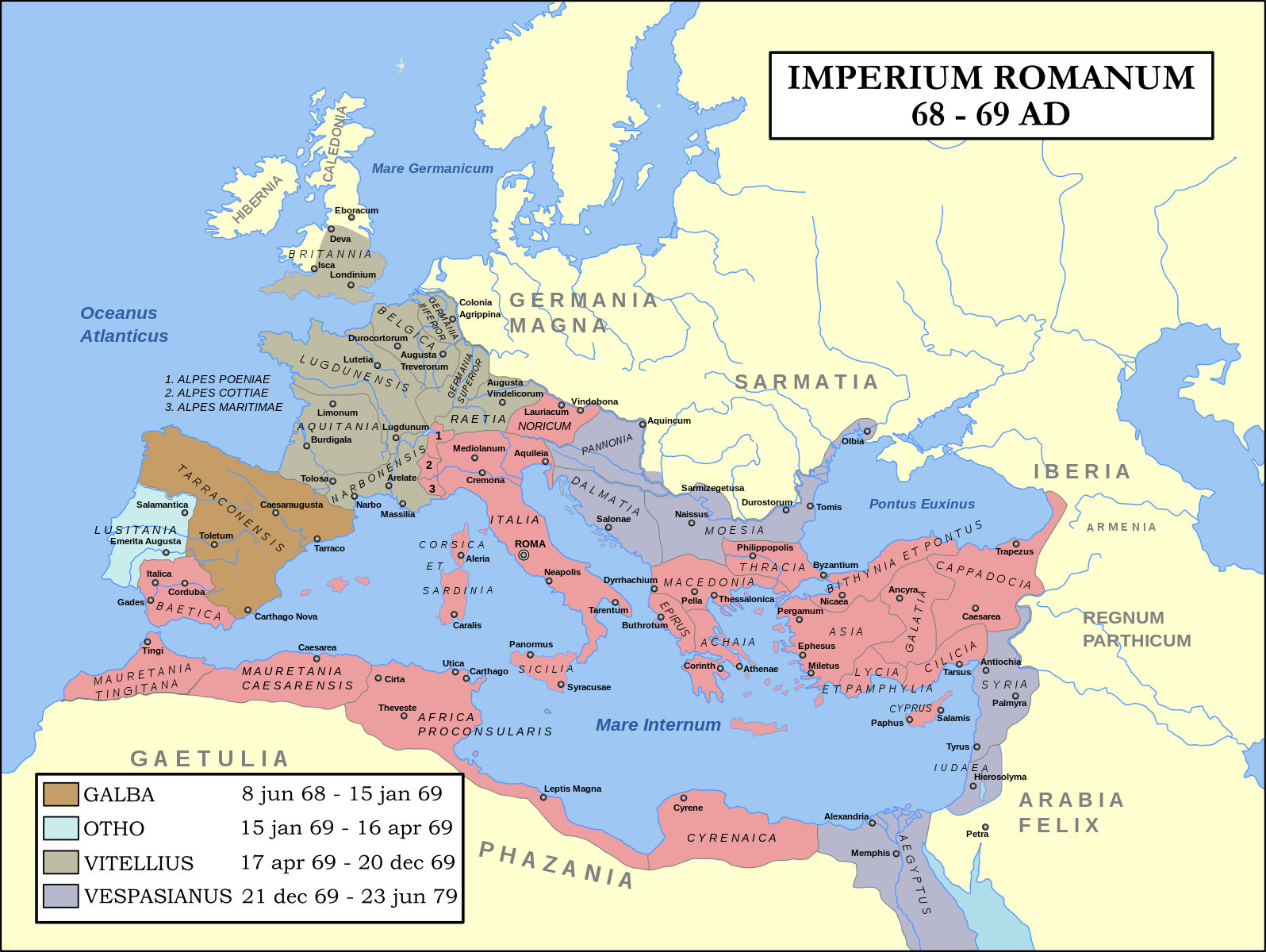

The Flavian Dynasty (Latin: Flavii), sometimes referred to as the First Flavian Dynasty, was a dynasty of Roman emperors that ruled from 69 to 96 AD. The founder, Vespasian (69–79), came to power after the Civil War (68–69).

Suetonius reports the humble origins of the Flavians, noting that they did not possess ancestral images (originally reserved for patricians, and later for all those who held high honorable positions). Under the Flavians, many representatives of provincial nobility were introduced into the Senate and the equestrian order. More broadly than their predecessors, the Julio-Claudians, the Flavians extended the rights of Roman and Latin citizenship to provincials, thus expanding the social base of imperial power. The policy pursued by the Flavians reflected the interests of the provincial nobility, causing discontent in the Senate in some cases.

The Flavian Dynasty was a Roman imperial dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire between 69 and 96 AD, including the reigns of Vespasian (69–79) and his two sons, Titus (79–81) and Domitian (81–96). The Flavians came to power during the Civil War of 69 AD, known as the Year of the Four Emperors. His claim to the throne was quickly challenged by legions stationed in the eastern provinces, who declared their commander Vespasian emperor instead. The second battle of Bedriacum tipped the balance decisively in favor of the Flavian forces, who entered Rome on December 20. The next day, the Roman Senate officially declared Vespasian emperor of the Roman Empire, thus beginning the Flavian dynasty. Although the dynasty did not last long, several significant historical, economic, and military events occurred during its reign.

Map of the Roman Empire during the Year of the Four Emperors

Map of the Roman Empire during the Year of the Four Emperors

Titus's rule was struck by a multitude of natural disasters, the most serious of which was the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD. The surrounding cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum were completely buried under ash and lava. A year later, Rome was hit by fire and plague. On the military front, the Flavian dynasty witnessed the siege and destruction of Jerusalem by Titus in 70 AD following the unsuccessful Jewish uprising of 66 AD. Significant conquests were made in Britain under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola between 77 and 83 AD, while Domitian failed to secure a decisive victory over King Decebalus in the war against the Dacians. In addition, the Empire strengthened its border defense by expanding fortifications along the Limes Germanicus.

The Flavians also initiated economic and cultural reforms. Under Vespasian, new taxes were developed to restore the finances of the Empire, and Domitian revalued the Roman coinage, increasing the silver content. Titus put into action a large-scale construction program to celebrate the ascent of the Flavian dynasty, leaving behind many enduring landmarks in Rome, the most impressive of which was the Flavian Amphitheater, better known as the Colosseum.

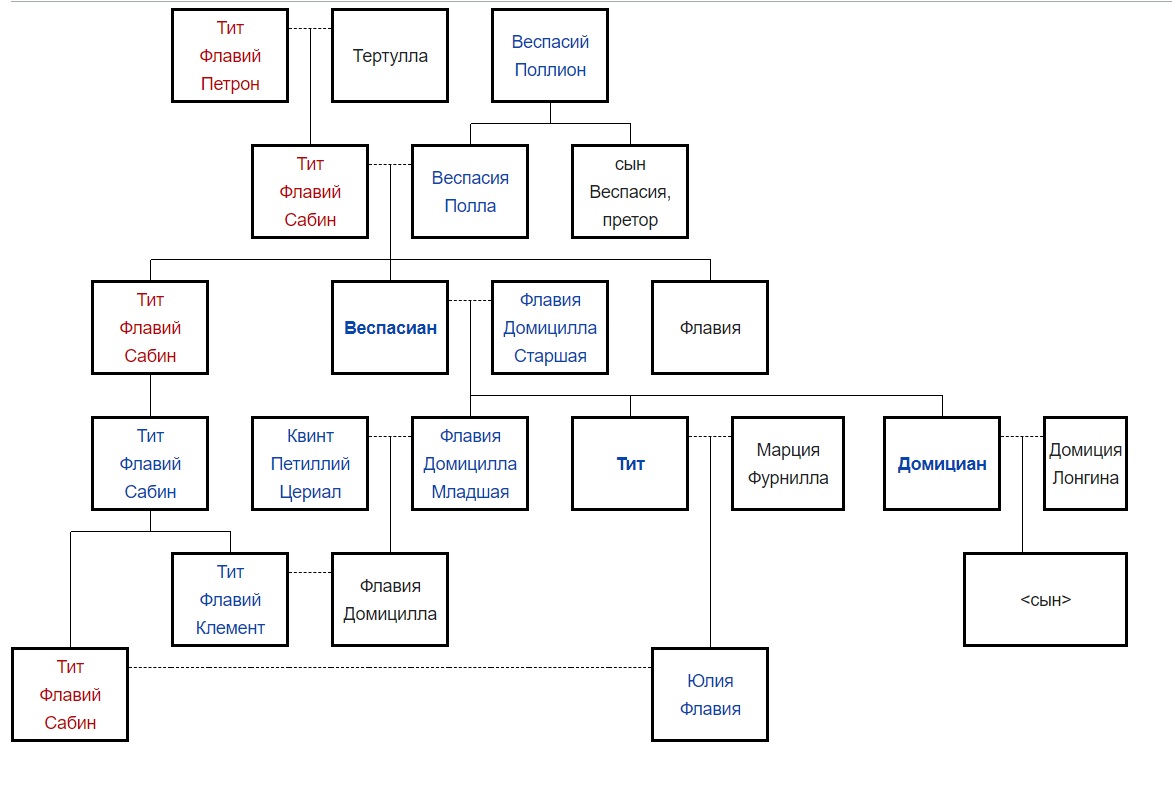

Genealogy

The decades of civil war in the 1st century BC contributed significantly to the decline of the old aristocracy of Rome, which was gradually replaced by a new Italian nobility in the early 1st century AD. One of such families were the Flavians, or the House of Flavius, who rose from relative obscurity to a prominent position in just four generations, acquiring wealth and status under the emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Vespasian's grandfather, Titus Flavius Petro, served as a centurion under Pompey during Caesar's civil war. His military career ended in disgrace when he fled from the battlefield at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. Nevertheless, Petro managed to improve his status by marrying the extremely wealthy Tertulla, whose fortune guaranteed the upward mobility of Petro's son, Titus Flavius Sabinus I. Sabinus himself earned further wealth and perhaps became an equestrian through his services as a tax collector in Asia and a banker in Helvetia (modern Switzerland). Marrying Vespasia Polla, he joined the more prestigious patrician Vespasian family, securing the elevation of his sons Titus Flavius Sabinus II and Vespasian to senatorial rank.

Around 38 AD, Vespasian married Domitilla the Elder, the daughter of a knight from Ferentium. They had two sons, Titus Flavius Vespasian (born in 39 AD) and Titus Flavius Domitian (born in 51 AD), and a daughter Domitilla (born in 45 AD). Domitilla the Elder died before Vespasian became emperor. After that, his mistress Caenis was his wife until she died in 74 AD. Vespasian's political career included the positions of quaestor, aedile, and praetor, and culminated in the consulship in 51 AD, when Domitian was born. As a military leader, he gained early fame by participating in the Roman invasion of Britain in 43 AD. However, ancient sources assert that the Flavian family was impoverished during the upbringing of Domitian, even claiming that Vespasian fell into disrepute under the emperors Caligula (37-41) and Nero (54-68). Modern history refutes these claims, assuming that these stories were later propagated under Flavian rule as part of a propaganda campaign aimed at diminishing successes under the less reputable emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty and maximizing achievements under Emperor Claudius (41-54) and his son Britannicus. Apparently, the imperial favor of the Flavians was high throughout the 40s and 60s. While Titus received a courtly education in the company of Britannicus, Vespasian was making a successful political and military career. After a long period of retirement during the 50s, he returned to public service under Nero, serving as proconsul in the province of Africa in 63, and accompanying the emperor during an official tour of Greece in 66.

From c. 57 to 59 AD Titus was a military tribune in Germany, and then served in Britain. His first wife, Arrecina Tertulla, died two years after their wedding, in 65 AD. Then Titus took a new wife from a more noble family, Marcia Furnilla. However, Marcia's family was closely connected with the opposition to Emperor Nero. Her uncle Barea Soranus and his daughter Servilia were among those who were killed after the failed Pisonian conspiracy of 65. Some modern historians suggest that Titus divorced his wife due to her family's connection to the conspiracy. He never married again. Titus had several daughters, at least one of them from Marcia Furnilla. The only one known to have lived to adulthood was Julia Flavia, possibly Titus's child from Arrecina, whose mother was also named Julia. During this period, Titus also practiced law and reached the rank of quaestor.

The Flavian family tree

The Flavian family tree

Vespasian

Little factual information has survived about Vespasian's government during his ten-year reign as emperor. Vespasian spent his first year as ruler in Egypt, during which the governance of the empire was handed over to Mucianus, assisted by Vespasian's son Domitian. Modern historians believe Vespasian stayed there to secure the support of the Egyptians. In the mid-70s, Vespasian first arrived in Rome and immediately began a large-scale propaganda campaign to strengthen his power and promote the new dynasty. His rule is most notable for financial reforms following the decline of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, such as the introduction of a tax on urinals and numerous military campaigns in the 70s. The most significant of these was the First Jewish-Roman War, which ended with the destruction of Jerusalem by Titus. In addition, Vespasian faced several revolts in Egypt, Gaul, and Germany and reportedly survived several conspiracies against him. Vespasian helped to restore Rome after the civil war, adding the Temple of Peace and beginning the construction of the Flavian Amphitheater, better known as the Colosseum. Vespasian died a natural death on June 23, 79 AD, and was immediately succeeded by his eldest son Titus. Ancient historians who lived during this period, such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus, and Pliny the Elder, speak well of Vespasian, condemning the emperors who were before him.

Titus

Despite initial fears about his character, Titus ruled successfully following Vespasian's death on June 23, 79 AD, and was considered a good emperor by Suetonius and other contemporary historians. In this role, he is best known for his public construction program in Rome and the completion of the Colosseum in 80 AD, as well as his generosity in alleviating the suffering caused by two disasters, the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD and the fire in Rome in the 80s. Titus continued his father's efforts to promote the Flavian dynasty. He revived the practice of the imperial cult, deified his father, and laid the foundation for what would later become the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, the construction of which was completed by Domitian. After barely two years in office, Titus unexpectedly died of fever on September 13, 81 AD, and was deified in the roman senate.

Domitian

Domitian was declared emperor by the Praetorian Guard the day after Titus's death, beginning a rule that lasted more than fifteen years - longer than any person who ruled Rome since the time of Tiberius. Domitian strengthened the economy by revaluing Roman coinage, expanded the boundaries of the Empire, and initiated a large-scale building program to restore the destroyed city of Rome. In Britain, Gnaeus Julius Agricola expanded the Roman Empire to modern Scotland, but in Dacia, Domitian failed to achieve a decisive victory in the war against the Dacians. On September 18, 96 AD, Domitian was killed by court officials, and with him came the end of the Flavian dynasty. On the same day, he was succeeded by his friend and advisor Nerva, who founded the venerable Nerva-Antonine dynasty. Domitian's memory was condemned to oblivion by the Roman Senate, with whom he had notoriously difficult relationships throughout his reign. Senatorial authors such as Tacitus, Pliny the Younger, and Suetonius published histories after his death promoting Domitian's image as a cruel and paranoid tyrant. Modern history has rejected these views, instead characterizing Domitian as a ruthless, but effective autocrat, whose cultural, economic, and political program laid the foundation for the peaceful principate of the 2nd century. His successors Nerva and Trajan were less strict, but in reality, their policy differed little from that of Domitian.

Domestic Policy

The Flavians also controlled public opinion through literature. Vespasian endorsed histories written during his reign, ensuring the elimination of biases against him, and also giving financial rewards to contemporary writers. Ancient historians living in this period, such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus, and Pliny the Elder, suspiciously speak well of Vespasian, condemning emperors who preceded him. Tacitus admits that his status was raised by Vespasian, Josephus identifies Vespasian as a patron and savior, and Pliny dedicated his "Natural Histories" to Vespasian's son, Titus. Those who spoke against Vespasian were punished. A number of Stoic philosophers were accused of corrupting students with inappropriate teachings and were banished from Rome. Helvidius Priscus, a philosopher advocating for the republic, was executed for his teachings.

Titus and Domitian also revived the practice of the imperial cult, which had somewhat fallen into disuse under Vespasian. Notably, Domitian's first act as emperor was the deification of his brother Titus. After their deaths, his minor son and niece Julia Flavia were also enrolled among the gods. To promote the worship of the imperial family, Domitian built a dynastic mausoleum on the site of Vespasian's former house on the Quirinal, and completed the construction of the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, a shrine dedicated to the worship of his deified father and brother. To immortalize the military triumphs of the Flavian family, he ordered the construction of the Templum Divorum and the Templum Fortuna Redux, and also completed the Arch of Titus. To further legitimize the divine nature of Flavian rule, Domitian also emphasized connections with the chief deity Jupiter, most notably through the impressive restoration of the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill.

Domitian's approach to governance was less subtle than that of his father and brother. Upon becoming Emperor, he quickly discarded the republican facade and transformed his government more or less formally into the divine monarchy he perceived it to be. By shifting the center of power to the imperial court, Domitian overtly annulled the powers of the Senate. He personally engaged in all branches of administration: decrees were issued regulating the minutest details of everyday life and law, while taxation and public morality were strictly enforced. Nevertheless, Domitian made concessions to senatorial opinion. Whereas his father and brother had effectively excluded non-Flavians from public service, Domitian rarely favored members of his own family in assigning strategic positions, admitting a surprisingly large number of provincials and potential opponents to the consulship, and appointing men of the equestrian order to manage the imperial bureaucracy.

Set of three aurei with Flavian images: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian.

Set of three aurei with Flavian images: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian.

One of Vespasian's first actions as Emperor was to implement a tax reform to replenish the Empire's exhausted treasury. After Vespasian arrived in Rome in the mid-70s, Mucian continued to insist that Vespasian collect as many taxes as possible, renewing old ones and introducing new ones. Mucian and Vespasian increased the tribute from the provinces and closely monitored treasury officials. The Latin proverb "Pecunia non olet" ("Money does not smell") may have originated when he introduced a urine tax for public toilets.

Upon his ascension to the throne, Domitian revalued the Roman coins to Augustus' standard, increasing the silver content in the denarius by 12%. The impending crisis of 85 AD, however, forced a devaluation to Nero's standard of 65, but it was still higher than the level Vespasian and Titus maintained during their rule, and Domitian's strict tax policy ensured this standard would be maintained for the next eleven years. Coin types of this era demonstrate an invariably high quality, including meticulous attention to Domitian's titling and exceptionally exquisite design on the reverse portraits.

Jones estimates Domitian's annual income to be more than 1.2 billion sestertii, over a third of which would likely be spent on maintaining the Roman army. Another significant expenditure relates to an extensive program of reconstruction in Rome itself.

Since the reign of Tiberius, the rulers of the Julio-Claudian dynasty had legitimized their rule through descendants by the adoptive line from Augustus and Julius Caesar. However, Vespasian could no longer claim such a connection. Therefore, a large-scale propaganda campaign was initiated to justify the Flavian rule as predetermined by divine providence. At the same time, Flavian propaganda emphasized Vespasian's role as a peacemaker after the crisis of 69 AD. Almost a third of all coins minted in Rome under Vespasian celebrated military victory or peace, while the word vindex was removed from coins to avoid reminding the public of the rebellious Vindex. Construction sites carried inscriptions praising Vespasian and condemning previous emperors, and the Temple of Peace was built in the forum.

The Flavians also controlled public opinion through literature. Vespasian approved histories written during his reign, ensuring the removal of prejudices against him and providing financial rewards to contemporary writers. Ancient historians living during this period, such as Tacitus, Suetonius, Josephus, and Pliny the Elder, suspiciously praise Vespasian, condemning the emperors who came before him. Tacitus admits that his status was elevated by Vespasian, Josephus identifies Vespasian as a patron and savior, and Pliny dedicated his "Natural Histories" to Vespasian's son, Titus. Those who spoke out against Vespasian were punished. Several Stoic philosophers were accused of corrupting students with unsuitable teachings and were expelled from Rome. Helvidius Priscus, a philosopher who advocated for the republic, was executed for his teachings.

Titus and Domitian also revived the practice of the imperial cult, which had somewhat fallen into disuse under Vespasian. Notably, Domitian's first act as emperor was the deification of his brother Titus. After their deaths, his minor son and niece Julia Flavia were also enrolled among the gods. To promote the worship of the imperial family, Domitian built a dynastic mausoleum on the site of Vespasian's former house on the Quirinal, and completed the construction of the Temple of Vespasian and Titus, a shrine dedicated to the worship of his deified father and brother. To immortalize the military triumphs of the Flavian family, he ordered the construction of the Templum Divorum and the Templum Fortuna Redux, and also completed the Arch of Titus. To further legitimize the divine nature of Flavian rule, Domitian also emphasized connections with the chief deity Jupiter, most notably through the impressive restoration of the Temple of Jupiter on the Capitoline Hill.

Military campaigns

The most significant military campaign undertaken during the Flavian period was the siege and destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD by Titus. The destruction of the city marked the climax of the Roman campaign in Judea following the Jewish rebellion of 66 AD. The Second Temple was completely destroyed, after which Titus' soldiers proclaimed him emperor in honor of the victory. Jerusalem was looted, and most of the population was killed or scattered. Josephus claims that 1,100,000 people were killed during the siege, most of whom were Jews. 97,000 were captured and enslaved, including Simon Bar Giora and John of Giscala. Many fled to regions of the Mediterranean. It is reported that Titus refused to accept a victory wreath, stating "there is no merit in defeating people deserted by their own God." Upon returning to Rome in 71 AD, Titus was honored with a triumph. Accompanied by Vespasian and Domitian, he entered the city, enthusiastically greeting the Roman population, preceded by a lavish parade with treasures and prisoners from the war. Josephus describes a procession with vast amounts of gold and silver carried along the route, followed by meticulously planned reconstructions of the war, Jewish prisoners, and finally treasures taken from the Jerusalem Temple, including the Menorah and the Torah. Resistance leaders were executed in the Forum, after which the procession concluded with religious sacrifices in the Temple of Jupiter. The Arch of Titus, which stands at one entrance to the forum, immortalizes Titus's victory.

The conquest of Britain continued under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, who expanded the Roman Empire to Caledonia, or modern Scotland, between 77 and 84 AD. In 82 AD, Agricola crossed an unidentified body of water and defeated peoples previously unknown to the Romans. He fortified the coast facing Ireland, and Tacitus recalls that his father-in-law often claimed that the island could be conquered by one legion and a few auxiliary forces. He gave refuge to an exiled Irish king, who he hoped could be used as a pretext for conquest. This conquest never occurred, but some historians believe the aforementioned crossing was actually a minor exploratory or punitive expedition to Ireland. The following year, Agricola assembled a fleet and pushed beyond the Fort into Caledonia. To aid the advance, an extensive legionary fortress was built at Inchtuthil. In the summer of 84 AD, Agricola encountered the armies of the Caledonians led by Calgacus at the Battle of Mons Graupius. Although the Romans inflicted heavy losses on the Caledonians, two-thirds of their army managed to escape and hide in the Scottish marshes and highlands, which ultimately hindered Agricola from taking the entire British island under his control.

Image from the Triumphal Arch of Titus, 1st century AD

Image from the Triumphal Arch of Titus, 1st century AD

The military campaigns undertaken during Domitian's reign were typically defensive in nature, as the Emperor rejected the idea of expansionist warfare. His most significant military contribution was the development of the Limes Germanicus, which covered an extensive network of roads, forts, and watchtowers built along the Rhine river to protect the Empire. Nevertheless, several important wars were waged in Gaul, against the Chatti, and across the Danube border against the Suevi, Sarmatians, and Dacians. Led by King Decebalus, the Dacians invaded the province of Moesia around 84 or 85 AD, inflicting significant damage and killing the Moesian governor Oppius Sabinus. Domitian immediately counterattacked, resulting in the destruction of a legion during an ill-fated expedition to Dacia. Their commander Cornelius Fuscus was killed, and the battle standard of the Praetorian Guard was lost. In 87 AD, the Romans again invaded Dacia, this time under the command of Tettius Julianus, and finally managed to defeat Decebalus at the end of 88 AD at the same place where Fuscus had been killed earlier. However, the assault on the Dacian capital was halted when a crisis arose on the German frontier, forcing Domitian to sign a peace treaty with Decebalus, which was harshly criticized by contemporary authors. Until the end of Domitian's reign, Dacia remained a relatively peaceful client kingdom, but Decebalus used Roman money to strengthen his defenses and continued to resist Rome. Only during Trajan's reign in 106 AD was a decisive victory over Decebalus ensured. Again, the Roman army suffered heavy losses, but Trajan managed to capture Sarmizegetusa and importantly, annex the gold and silver mines of Dacia.

Results

The Flavians, although they were a relatively short-lived dynasty, helped to restore the stability of an empire on its knees. Although all three were criticized, particularly because of their more centralized style of governance, they implemented reforms that created a sufficiently stable empire to last until the 3rd century. However, their military dynasty led to further marginalization of the Senate and a decisive departure from the princeps, or first citizen, to the emperor or imperator.

Little factual information has survived about Vespasian's government during the ten years he was emperor, his reign is most known for its financial reforms after the decline of the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Vespasian was characterized by his gentleness and dedication to the people. For example, a lot of money was spent on public works, the restoration and improvement of Rome: a new forum, the Temple of Peace, public baths, and the Colosseum.

The service list of Titus among ancient historians is considered one of the most exemplary for any emperor. All the surviving stories of this period, many of which were written by his contemporaries such as Suetonius Tranquillus, Cassius Dio, and Pliny the Elder, present a quite favorable view of Titus. His character particularly excelled compared to his brother Domitian. Unlike the idealized image of Titus in Roman histories, in Jewish memory "Titus the Impious" is remembered as a wicked oppressor and destroyer of the Temple. For example, one legend in the Babylonian Talmud describes Titus as having sex with a whore on a Torah scroll inside the Temple during its destruction.

Although contemporary historians vilified Domitian after his death, his administration laid the groundwork for the peaceful 2nd century AD empire and the culmination of the "Pax Romana". His successors Nerva and Trajan were less autocratic, but in reality their policies differed little from Domitian's. The Roman Empire flourished between 81 and 96 AD, which was much more than the gloomy code for the 1st century, during a period of rule that Theodor Mommsen described as the gloomy but sensible despotism of Domitian.

Related topics

Roman Empire, Emperors of Rome, Reign of the Julio-Claudian dynasty

Literature

Contemporary authors:

- Granger, John D. (2003). Nerva and the crisis of the Roman succession 96-99 London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-28917-3

- Jones, Brian W. (1992). The Emperor Domitian. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10195-6

- Jones, Brian W.; Milnes, Robert (2002). Suetonius: The Flavian Emperors: a historical commentary. London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-85399-613-0

- Murison, Charles Leslie (2003). " M. Cocceus Nerva and the Flavians "(subscription required). Proceedings of the American Philological Association. University of Western Ontario. 133 (1): 147–157. DOI : 10,1353 / apa.2003.0008

- Sullivan, Philip B. (1953). "A note on the accession of the Flavians". Classic magazine. Classical Association of the Midwest and South, Inc. 49 (2): 67-70. JSTOR 3293160

- Syme, Ronald (1930). Imperial Finance under Domitian, Nerva, and Trajan. Journal of Roman Studies. 20 : 55–70. DOI : 10.2307 / 297385. JSTOR 297385

- Townend, Gavin (1961). "Some Flavian connections". Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Advancement of Roman Studies, 51 (1 and 2): 54-62. DOI : 10.2307 / 298836. JSTOR 298836

- Waters, KH (1964). "The Character of Domitian". Phoenix. Classical Association of Canada. 18 (1): 49–77. DOI : 10.2307 / 1086912. JSTOR 1086912

- Wellesley, Kenneth (1956). "Three historical riddles in Story 3". The Classical Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. 6 (3/4): 207–214. DOI : 10.1017 / S0009838800020188. JSTOR 636914

- Wellesley, Kenneth (2000) [1975]. The Year of the Four Emperors. Roman-Imperial biographies. London: Routledge, p. 272. ISBN 978-0-415-23620-1

- Jones, Brian W. (1984). The Emperor Titus. London: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-312-24443-6

- Levick, Barbara (1999). Vespasian (Roman Imperial biographies. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-16618-7

Ancient authors:

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- Josephus, The Jewish War

- Suetonius, On the life of the Caesars

- The Life of Vespasian

- Tacitus, Agricola

- Tacitus, Stories