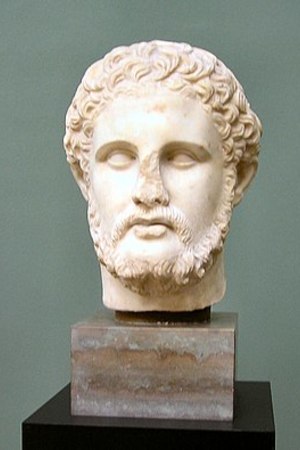

Philip II

Philip II (Ancient Greek: Φίλιππος Β'; 382–336 BC) was a Macedonian king, reigning from 359 BC. Philip II is primarily remembered as the father of Alexander the Great, although he completed the most difficult initial task of strengthening the Macedonian state and effectively uniting Greece within the framework of the Corinthian League. His son later used the strong, battle-hardened army formed by Philip to create his vast empire.

Ascension to Power

Philip II was born in 382 BC in the city of Pella, the capital of ancient Macedonia. His father was King Amyntas III, and his mother, Eurydice, came from the noble Lyncestis family, which had ruled independently in northwestern Macedonia for a long time. After the death of Amyntas III, Macedonia gradually disintegrated under the pressure of Thracian and Illyrian neighbors, and the Greeks also took every opportunity to gain control over the weakening kingdom. Around 368–365 BC, Philip was held hostage in Thebes, where he became acquainted with the organization of social life in ancient Greece, mastered the basics of military strategy, and was exposed to the great achievements of Hellenic culture. In 359 BC, invading Illyrians captured part of Macedonia and defeated the Macedonian army, killing King Perdiccas III, Philip's brother, and another 4,000 Macedonians. The son of Perdiccas III, Amyntas IV, was enthroned, but due to his minority, Philip became his guardian. Having started ruling as a guardian, Philip soon won the trust of the army and, having pushed aside the heir, became the king of Macedonia at a difficult time for the country at the age of 23.

Demonstrating an extraordinary diplomatic talent, Philip quickly dealt with his enemies. He bribed the Thracian king and convinced him to execute Pausanias, one of the claimants to the throne. He then defeated another contender, Argaeus, who had the support of Athens. To secure himself against Athens, Philip promised them Amphipolis, thus freeing Macedonia from internal turmoil. Having strengthened and grown stronger, he soon took control of Amphipolis, managed to control the gold mines, and began minting gold coins. Using these funds to create a large standing army, the basis of which was the famous Macedonian phalanx, Philip also built a fleet, was one of the first to widely use siege and throwing machines, and skillfully resorted to bribery (his expression is known: "A donkey loaded with gold will take any fortress"). This gave Philip great advantages, his neighbors were disorganized barbarian tribes on one side, and on the other, the Greek polis world in deep crisis, as well as the Achaemenid Persian Empire, which was already disintegrating at that time.

Silver tetradrachm of Philip II from the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

Silver tetradrachm of Philip II from the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

Establishment of Macedonian Hegemony

Philip entered Greece not as a conqueror, but at the invitation of the Greeks themselves, to punish the inhabitants of Amphissa in central Greece for their unauthorized seizure of sacred lands. However, after the devastation of Amphissa, the king was not in a hurry to leave Greece. He seized a number of cities from where he could easily threaten the main Greek states.

Thanks to the energetic efforts of Demosthenes, a long-standing opponent of Philip, and now one of the leaders of Athens, an anti-Macedonian coalition was formed between a number of cities; through the efforts of Demosthenes, the strongest of them, Thebes, which until now had been in alliance with Philip, was attracted to the coalition. The long-standing enmity between Athens and Thebes gave way to a sense of danger from the growing power of Macedonia. The combined forces of these states tried to drive the Macedonians out of Greece, but unsuccessfully. In 338 BC, the decisive Battle of Chaeronea took place, ending the glory and greatness of ancient Hellas.

The defeated Greeks fled from the battlefield. Unrest, nearly turning into panic, seized Athens. To curb the desire to flee, the assembly passed a resolution stating that such acts were considered treason and were punishable by death. The residents began energetically strengthening the city walls, accumulating food, all the male population was called up for military service, and freedom was promised to the slaves. However, Philip did not go to Attica, remembering the unsuccessful siege of Byzantium and the Athenian fleet of 360 triremes. After dealing harshly with Thebes, he offered Athens relatively mild peace terms. The forced peace was accepted, although the words of the orator Lycurgus about those who fell on the fields of Chaeronea reflect the mood of the Athenians: "For when they parted with life, Hellas was enslaved, and along with their bodies, the freedom of the other Hellenes was buried."

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Corinthian Congress

Literature

- F. F. Zelinsky, A. I. Georgievsky, M. S. Kutorga, F. Gelbke, P. V. Nikitin, V. A. Kansky, per. A.D. Weisman, F. Gelbke, L. A. Georgievsky, A. I. Davidenkov, V. A. Kansky, P. V. Nikitin, I. A. Smirnov, E. A. Vert, O. Yu. Klemenchich, N. V. Rubinsky — St. Petersburg: Society of Classical Philology and Literature. pedagogiki Publ., 1885, pp. 1027-1029.

- F. F. Zelinsky, A. I. Georgievsky, M. S. Kutorga, F. Gelbke, P. V. Nikitin, V. A. Kansky, per. A.D. Weisman, F. Gelbke, L. A. Georgievsky, A. I. Davidenkov, V. A. Kansky, P. V. Nikitin, I. A. Smirnov, E. A. Vert, O. Yu. Klemenchich, N. V. Rubinsky — St. Petersburg: Society of Classical Philology and Pedagogy 1885, pp. 950-951.

- Diodorus of Sicily. Historical library.