Corinthian Congress

The Corinthian Congress of 338/337 BCE was a gathering of representatives from nearly all Greek city-states on the Balkan Peninsula, convened by Philip II of Macedon with the aim of achieving a universal peace and creating a Pan-Hellenic alliance. This event effectively marked the culmination of the process of subjugating the Balkan Greece to Macedonian dominance.

After the Battle of Chaeronea, Philip embarked on a campaign in Southern Greece. All the cities of the Peloponnesian League, except for Sparta, recognized the authority of the Macedonian king. Philip avoided the practice of unilateral dictates. With each city individually, he concluded defensive and offensive alliances, which were based on the preservation of the internal autonomy and freedom of each respective city. In order to address matters concerning all of Greece, Philip convened a pan-Greek assembly called the Corinthian Congress (Synedrion) in Corinth in 338 BCE. All Greek city-states were represented at the congress, except for Sparta.

Philip himself presided over the congress. The congress proclaimed the end of war in Greece and the establishment of a general peace. They then proceeded to discuss other matters. Greek fragmentation was overcome by creating a Pan-Hellenic federation, which included Macedonia and was chaired by the Macedonian king.

An eternal defensive and offensive alliance was concluded between the united city-states and the Macedonian king. Under the threat of severe punishment, no state or Greek individual was allowed to oppose the king or assist his enemies. Any disputes that arose between Greek city-states were referred to the court of the Amphictyonic League. Philip served as the head of the Amphictyonic council. Acts such as changes in the city's constitution, confiscation of property, debt cancellation, incitement of slave rebellion, etc., were considered criminal offenses. In conclusion, the congress decided to initiate a war against Persia. Philip hoped to divert attention from Greek affairs with a "swift and victorious" war in Asia. The same Philip was appointed as the leader (hegemon) of the allied Greek forces. The word "king" does not appear in the acts of the Corinthian Congress. In his dealings with the Greeks, Philip never referred to himself as a king (basileus). To the free Hellenes, he was not a basileus but a hegemon.

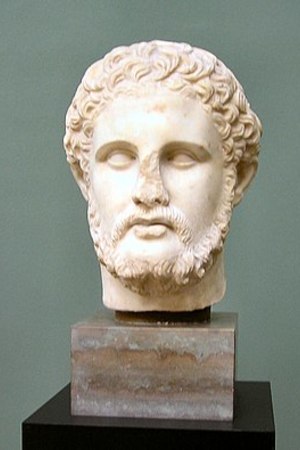

Silver tetradrachm of Philip II from the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

Silver tetradrachm of Philip II from the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

Related topics

Literature

- Frolov, E. D., The Corinthian Congress of 338/7 BC and the Unification of Hellas, in Borza, Yu. N., Istoriya antichnoi Makedonii (do Aleksandra Velikogo). - St. Petersburg: Faculty of Philology of St. Petersburg State University; Nestor-Istoriya, 2013-592 p — - ISBN 978-5-8465-1367-9

- Kholod M. M. Shadow of the Heronean Lion: the assertion of Macedonian domination in Greece in 338 BC / / Problems of Ancient History. Collection of scientific articles dedicated to the 70th anniversary of Professor E. D. Frolov. Edited by A. Y. Dvornichenko, Doctor of Historical Sciences, St. Petersburg, 2003. ISBN 5-288-03180-0