Roman Streets

The description of ancient Roman streets should be conducted using examples from cities like Rome and Pompeii. By the end of the Republican period, Rome, as the capital of an expanding state, was a large, densely populated city with many multi-story buildings (insulae) and numerous small, narrow streets (the widest being about 6-7 meters). The narrow width of the streets in ancient cities of the Apennine Peninsula was due to the need to conserve living space within the city limits, which were confined by the city walls. Living outside the walls was unsafe due to the threat of attacks. The scorching sun and the need for shade in southern cities often turned the close arrangement of buildings into an advantage, as the heat was mitigated by the shadows cast on the narrow streets (Sokolov G.I. Art of Ancient Rome, p. 46).

It was quite easy for a foreigner or even a non-local resident to get lost in the vast city. While the main street of a district always had a name, small streets, dead-ends, and alleys often remained unnamed (Sergienko E.M. Life in Ancient Rome, p. 18). And this was not all the trouble that could await a newcomer. The main, central streets got their names from a craftsman or merchant living there, from a legendary event supposedly taking place on that street, or simply from the person who laid the street. Despite the fact that there were a great many such streets, they did not have identification signs. In simpler terms, streets, like houses, were not labeled. To find a needed street, a person had to orient themselves, for example, by the shops or workshops, or by the house of some notable person, which might be located on one of the streets. Another drawback of Roman streets, besides those mentioned above, was their narrowness.

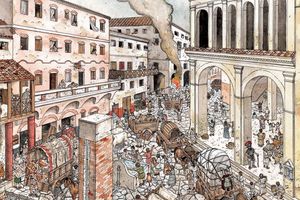

The average street width was 5-5.5 meters, and alleys and dead-ends could be less than 3 meters. It is noteworthy that the width of the same street varied: for example, the Sacred Road was 6.5 meters at its widest point and 4.8 meters at its narrowest. Such street planning was due to the conservation of living space. Unlike the small cities of Republican Rome, such as Pompeii, where daytime movement was only pedestrian, in Rome until 45 B.C. one could move around the streets both on foot and by horse and cart, which caused great dissatisfaction among the residents of Rome. Here is how Juvenal describes what happened on the Roman streets: "The noise of wagons jostling in the narrow alley, and the curses of the drivers can wake even seals! When a rich man has some business, he rides through the crowd, and while a tall Liburnian carries him over the heads, he reads, writes, or sleeps, as nowhere is it better to sleep than in a closed litter. And he arrives before us, no matter how we hurry, because the crowd standing ahead stops us, we are pushed by those coming from behind. One hits me with an elbow, another with a knee, yet another log bangs against my head, and my head hits a jar. My legs are covered in greasy dirt. From all sides, I'm being trampled on, a soldier's boot nail has pierced my big toe... One must be a totally indifferent person, unwilling to foresee any accidents, to go out to dinner in the city without having made a will in advance. On your way, there are as many deaths as there are open windows. All you can wish for is that from the windows you are only doused with slops. And here is a bold drunkard, tormented because he has not yet fought with anyone." (Juvenal, III, 222). Such were the streets of ancient Rome.

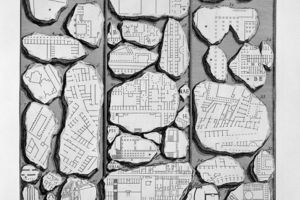

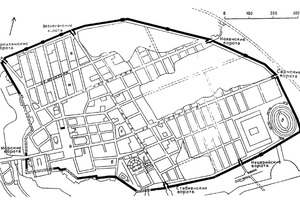

Now let's move on to examining the layout of streets in other, smaller cities. A good example here is Pompeii. This city, which perished during the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 AD, is a gift for modern archaeologists and historians. Due to this tragedy, the city, if one can say so, was preserved. Unlike Rome, which survived many eras, each leaving its mark on the city's layout, Pompeii was not subjected to any changes. The city was covered with volcanic ash; much was damaged, not to mention the number of casualties, but the city's layout, paved streets, ground floors of buildings, mosaics, and paintings were preserved. Pompeii was not the capital of a state, and street life in the city, if one may say so, was more peaceful. The streets and alleys known to us from excavations did not exceed 10 meters in width. The widest of the seven streets uncovered to date is Mercury Street, laid from north to south, leading to the city center - the forum - and serving as the main axis of the city for some time. Historical names of the streets remain unknown, so archaeologists named the streets during excavations based on their direction (e.g., Stabian, Nola - these are streets leading to the cities of Stabiae and Nola) or based on more important and characteristic buildings located on these streets (Euamachia Street - named after the wool market built by Euamachia; Hanging Balcony Street, named after a house whose protruding enclosed balcony defined the appearance of the entire alley), or finally by their general appearance (Crooked Alley). The Street of Abundance was named after an image on a well at its beginning (this image was taken to be a figure of Abundance) (Sergienko M.E. Pompeii, p. 25). It is important to note that the streets of Pompeii were better arranged than the streets of Rome: they had pavements with sidewalks; to cross from one side of the street to the other, one could avoid stepping onto the roadway by using rows of stones lying at almost every intersection. These stones were spaced so that at night, cart wheels could easily pass between them. Riding horses and using carts during the day was prohibited for safety reasons. Wealthy citizens could move around in litters during the day. The streets had fountains with fresh water supplied from the Campanian mountains.

Literature

1. Sergeenko M. E. Pompeii. Moscow-Leningrad, Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1949

2. Sergeenko E. M. Life of ancient Rome [Life of ancient Rome]. St. Petersburg, Neva Publ., 2002.

3. Sokolov G. I. Art of Ancient Rome [The Art of Ancient Rome]. Moscow, Iskusstvo Publ., 1971

4. Decimus Junius Juvenal. Satires. Saint Petersburg, Alethea Publ., 1994