Reforms of Solon

Solon (Ancient Greek: Σόλων; between 640 and 635 BC, Athens — circa 559 BC, Athens) was an Athenian statesman, lawmaker, and poet, and one of the "Seven Sages" of Ancient Greece.

Solon came from the noble Codrid family, which was once a royal dynasty. It appears that even before his political career, he was known to his fellow citizens as a poet. He was the first Athenian poet, and the political nature of some of his verses must have drawn the attention of his audience. Solon's political career began with his expedition to Salamis during the war with Megara. After the successful expedition, he initiated the First Sacred War. By 594 BC, he had become the most influential and authoritative political figure in Athens.

Solon was elected archon eponymous for the year 594/593 BC. In addition, he was granted extraordinary powers. Solon carried out a series of reforms (such as the Seisachtheia, property census, establishment of the jury courts, and the Council of Four Hundred, among others) that represent a major milestone in the history of archaic Athens and the formation of the Athenian state. After his archonship, the reformer embarked on a journey that took him to various regions of the Eastern Mediterranean. After his travels, Solon no longer took an active role in political life. He died around 559 BC in Athens.

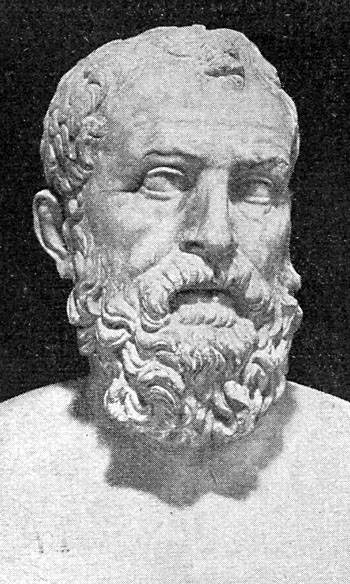

Bust of Solon, National Archaeological Museum of Naples

Bust of Solon, National Archaeological Museum of Naples

It is possible that by this time Solon had already formulated his plan for reforms. To implement them, he needed to secure high-authority religious sanction. The Delphic Oracle provided Solon with several prophecies approving his plans. By 594 BC, Solon was the most influential and respected political figure in Athens, and he was seen as a compromise figure by all social strata (aristocrats, commoners, merchants, and craftsmen).

In 594 BC, Solon was elected archon eponymous and granted certain extraordinary powers. According to Plutarch, he was appointed "reconciler and lawmaker," while Aristotle noted that the state was "entrusted to him." His extraordinary powers were likely encapsulated in the term "reconciler, arbitrator." Thus, his task was to resolve the conflict and reconcile the warring parties. At that time, archons were appointed by the Areopagus, but Solon was probably elected by the popular assembly due to the special circumstances.

His first reform was the Seisachtheia, which he considered his greatest achievement. All debts were canceled, debt-slaves were freed, and debt slavery was prohibited. The Seisachtheia was meant to significantly reduce social tension and improve the state's economic condition.

Solon implemented a comprehensive economic policy characterized by protectionism towards Athenian agriculture and support for artisanal production. Craftsmen from other cities who came to Athens were allowed to settle in the city. Another law stated that parents who did not teach their sons a trade had no right to expect support from them in old age. He banned the export of grain from Athens and encouraged olive cultivation. Thanks to Solon's measures, olive cultivation eventually became a thriving sector of agriculture. Solon's monetary reform involved replacing the previous Aeginetan standard with the Euboean standard. This measure facilitated trade between Athens, Euboea, Corinth, Chalcidice, and Asia Minor, and contributed to the development of Athenian foreign trade.

Solon's social reforms were also of great importance. The most significant of these was the division of the entire citizen body of the polis into four property classes. The criterion for belonging to a particular class was the amount of annual income, calculated in agricultural produce.

- Pentacosiomedimnoi: Those with an income of more than 500 medimnoi of grain, or 500 metretai of wine or olive oil, could be elected as archons and treasurers.

- Hippeis: Those with an income of more than 300 medimnoi of grain could maintain a warhorse.

- Zeugitae: Those with an income of more than 200 medimnoi of grain served as hoplites.

- Thetes: Those with an income of less than 200 medimnoi of grain could participate in the popular assembly and jury courts.

The poorest citizens (thetes), unlike the Athenians in the first three property classes, were not eligible for public office and could only participate in the popular assembly and jury courts (heliaia). According to the most common interpretation, Solon implemented this reform in the interests of the wealthy (primarily the non-aristocratic rich from among the craftsmen and traders). However, the poor also benefited: they could now participate in political life.

It seems likely that Solon also established the heliaia. This innovation had the most democratic character. Solon granted any citizen the right to bring a lawsuit in a case that did not directly concern them. Previously, Athens only had private lawsuits and trials where the plaintiff had to be the injured party themselves, but now public lawsuits and trials appeared.

Solon also established another new governmental body—the Council of Four Hundred. Its members were representatives of the four Attic tribes, with 100 men from each tribe. The Council of Four Hundred was an alternative to the Areopagus. The division of functions between them was not precisely defined. According to Plutarch, the Council of Four Hundred prepared and preliminarily discussed bills for the popular assembly, while the Areopagus exercised "oversight over everything and protection of the laws."

Solon enacted a law on wills. Plutarch conveys the content of the law as follows: previously, "it was not allowed to make wills; the money and household of the deceased had to remain within his kin; but Solon allowed those who had no children to leave their estate to anyone they wished." Solon was the first in Athenian history to introduce the institution of wills. Additionally, a land maximum was introduced (prohibiting land holdings beyond the legally established norm).

Solon's code of laws was inscribed on wooden tablets (kyrbeis) and displayed for public view. This code was meant to replace Draco's code; only Draco's laws on homicide continued to be in force. The new code of laws was supposed to remain in effect for 100 years but actually lasted even longer.

The reforms of Solon represent a major milestone in the history of archaic Athens and the formation of the Athenian state.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Athenian Democracy

Literature

- Lentsman Ya. A. The authenticity of the ancient tradition about Solone / / Drevnyj mir: sbornik statej v chve akademika V. V. Struve. - Moscow: Izd-vo vostochnogo lit., 1962.

- Lurie S. Ya. Solon i nachalo revolyutsii v Afinakh [Solon and the beginning of the Revolution in Athens]. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Publishing House, 1993, 680 p.

- Sergeev V. S. History of Ancient Greece. - SPb.: Polygon, 2002. - 704 p — - ISBN 5-89173-171-1.