Sparta

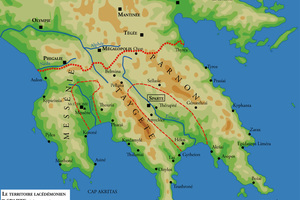

Sparta (Ancient Greek: Σπάρτη, Latin: Sparta) or Lacedaemon (Ancient Greek: Λακεδαίμων, Latin: Lacedaemon) was an ancient state in Greece located in the region of Laconia in the southern part of the Peloponnesian Peninsula.

The foundation of the Spartan state, usually dated to the 8th–7th centuries BC, was based on the general patterns of the disintegration of the primitive communal system. However, while in Athens these patterns led to the near-complete disappearance of tribal relations, in Sparta, the process of state formation was marked by significant differences and accompanied by the preservation of substantial remnants of the tribal organization.

A key feature of Sparta’s historical development was the intervention of an external violent factor in the formation of class society. The migration of tribes on the Balkan Peninsula, which began in the 12th century BC, was accompanied by military clashes between them. The union of the conquering Dorian tribes with the local Achaean population in the valley of Laconia led to the formation of the Spartan community, allowing it to expand its territories in the 8th–7th centuries BC, subjugate the population of the neighboring region of Messenia, and place the peripheral inhabitants of the conquered territory into a dependent status.

The conquest led to the establishment of joint ownership of land— the primary means of production at the time—and slaves among the conquerors. Alongside this, a clear class differentiation emerged: the Spartiates became the dominant class of slave owners, while the conquered people were reduced to slaves or less privileged citizens.

The political organization of the Spartiates was typical for the period of the disintegration of the primitive communal system, featuring two tribal chiefs (a result of the union between the Dorian and Achaean tribes), a council of elders, and a popular assembly. However, this structure did not provide sufficient means to maintain dominance over the subjugated population, whose numbers were approximately twenty times greater than those of the conquerors. This created an objective need for a political power structure distinct from the general population, one that could ensure the dominance of a small ruling class over a large enslaved population.

At the same time, the need to dominate the enslaved masses and ensure their exploitation required the Spartiates to maintain unity and preserve certain elements of tribal community. This was facilitated by Sparta’s agrarian economy, the relative isolation of its territory—enclosed by mountain ranges—that hindered the development of external trade and monetary relations. These factors combined to preserve significant elements of military democracy even within the fully formed class society.

The social and political structure of Sparta during this period was codified by the rhetra (a decree), attributed to the legendary lawgiver Lycurgus. Lycurgus, as a historical figure, probably did not exist, and the exact time of his reforms has not been determined. It is believed that the rhetra dates to the 8th–7th centuries BC, with the final establishment of the "Lycurgan system" occurring by the end of the 7th–early 6th century BC. The rhetra (possibly there were several) aimed to address two main objectives: to ensure the unity of the Spartiates by restraining economic inequality among them, and to create an organization of their collective dominance over the subjugated population.

Features of the Social System

In Sparta, a unique class-based slave-owning society developed, retaining significant remnants of the primitive communal system.

The ruling class consisted of the Spartiates. Only they were considered full citizens. Despite the preservation of communal land ownership among citizens, membership in the ruling class was maintained by granting each Spartiate the use of a plot of land (kleros) along with the helots attached to it. The labor of the helots provided for the Spartiate and his family. The land was divided into approximately 9,000 equal, indivisible, and inalienable kleroi. These plots could not be sold, gifted, or bequeathed.

The Spartiates lived in a quasi-city, which was a union of five villages resembling a military camp. Their daily life was strictly regulated. Their primary duty was military service. To prepare children for this duty, they were taken at the age of seven for state upbringing in special schools. Special officials called paidonomoi instilled discipline, unquestioning obedience to elders, strength, endurance, military skills, and courage. Training concluded at the age of 20. From 20 to 60 years old, Spartiates were required to serve in the military. Adult men were grouped into age-based and other associations that determined the social status of their members. A select few citizens were part of the privileged corps of 300 horsemen. Women, almost entirely freed from household chores and childcare, enjoyed some independence and had the leisure to develop their personalities.

To maintain unity, Spartiates were required to participate in communal meals called syssitia, organized through monthly contributions from the Spartiates. The portions in the syssitia were equal, although officials received honorary shares. The warriors wore the same clothing and armor. The unity of the Spartiates was further reinforced by the rules against luxury established by Lycurgus. Spartiates were forbidden to engage in trade, and they used heavy, cumbersome iron coins.

However, these restrictions could not prevent the development of economic differentiation, which undermined the unity and "equality" of the Spartiates. Since land allotments were inherited only by the eldest sons, the others could only receive unclaimed plots. If none were available, they would fall into the category of hypomeiones (the fallen) and lose the right to participate in the assembly and syssitia. The number of hypomeiones steadily increased, while the number of Spartiates correspondingly decreased—from nine thousand to four thousand by the end of the 4th century BC.

The Perioeci—inhabitants of the peripheral mountainous and infertile regions of Sparta—occupied an intermediate legal status between the Spartiates and the helots. They were personally free, had property rights, but did not enjoy political rights and were under the supervision of special officials called harmosts. They were subject to military service and had to participate in battles as heavily armed soldiers. The main occupations of the Perioeci were trade and craftsmanship. Their status was similar to that of the metics in Athens, but unlike the latter, the highest officials of the state could execute them without trial.

The Helots—the enslaved inhabitants of Messenia—were considered the property of the state. They were assigned to Spartiates, worked their land, and gave up about half of the harvest (for domestic work, the Spartiates used slaves captured in war). Although in Sparta, as in Athens, the exploitation of slave labor became the foundation of social production, collective Spartan slavery differed from classical slavery. Helotry was a specific form of slavery. Helots essentially ran their own households independently, were not treated as commodities like traditional slaves, and had control over the portion of the harvest they kept. Their economic and social status was closer to that of serfs. It is believed that they had families and formed a sort of community, which was the collective property of the Spartan community.

Helots participated in Sparta's wars as lightly armed soldiers. They could buy their freedom, but in other respects, they were completely disenfranchised. Every year, the Spartiates declared war on the helots, which was accompanied by mass killings. However, the killing of a helot was permissible at any time.

Organization of Power

The governmental structure of Sparta evolved from a military democracy into a state organization that retained some elements of tribal governance. This transformation led to the establishment of the "Lycurgan system," which, as noted, was fully developed by the 6th century BCE. Some historians view this as a revolution, linked to the completion of the conquest of Messenia and the establishment of helotage, necessitating the consolidation of the Spartiate community through economic and political equality, transforming it into a military camp that dominated over the enslaved population.

At the head of the state were two archagetas. In literature, they are often referred to as kings, although even the Athenian basileus, to whom the term "king" is also somewhat loosely applied, held more power than the Spartan leaders. The power of the archagetas, unlike that of tribal leaders, became hereditary, though it was not firmly established. Every eight years, a star-gazing ritual was conducted, after which the archagetas could be put on trial or removed from office. Sometimes they were deposed without this procedure.

However, the position of archagetas was generally honorary. They received a significant portion of the war spoils, performed sacrifices, were part of the council of elders, administered justice in certain cases of importance to the community, and initially held significant military power. They commanded the army and had the right of life and death during campaigns. Over time, however, their military authority was significantly curtailed.

The Council of Elders (gerousia), like the archagetas, was an institution inherited from tribal organization. The gerousia consisted of 28 gerontes, who were elected for life by the assembly from among the noble Spartiates who had reached the age of 60. The two leaders (archagetas) were also members. Initially, the gerousia reviewed matters to be discussed by the assembly, allowing it to guide its activities. Over time, the powers of the gerousia expanded. If the gerontes and the leaders disagreed with the assembly's decision, they could obstruct it by leaving the meeting. The gerousia also participated in negotiations with other states, reviewed criminal cases of state crimes, and conducted trials against the archagetas.

The Assembly (apella) included all Spartiates aged 30 and over. Initially, it was convened by the leaders, who also presided over it. Only officials or foreign envoys could speak in the assembly, while the participants listened and voted. Voting was done by shouting, and in disputed cases, the assembly members would separate into different groups.

The assembly met once a month, unless an emergency required otherwise. It passed laws, elected officials, decided on matters of war and peace, alliances with other states, considered issues of leadership succession, determined who among the leaders would command the army during campaigns, and so on. Due to its procedural limitations, the assembly had less influence than the Athenian ekklesia. However, its role should not be underestimated. The right to elect officials and reject proposals allowed the assembly, if not to control them, then at least to influence them and compel them to take it into account. By the 4th century BCE, however, the assembly became more passive, and its role diminished.

The Ephors emerged in Sparta in the 8th century BCE as a result of intense conflicts between tribal leaders and the aristocracy. The latter, who received a larger share of war spoils and the opportunity to oppress free citizens, sought to limit the lifetime power of the leaders by creating a body of elected aristocratic representatives. These representatives became the five ephors, elected from the "worthy" for one-year terms, acting as a collegial body that made decisions by majority vote. Initially, the ephors were seen as assistants to the archagetas and dealt with judicial matters concerning property disputes. From the mid-6th century BCE, the power of the ephors significantly increased. They placed the archagetas under their control—two ephors would accompany them on campaigns. Ephors gained the right to convene the gerousia and the assembly and to direct their activities. Along with the gerousia, they could prevent the assembly from making decisions they opposed. They took charge of Sparta’s foreign relations and internal administration, ensured compliance with Spartan customs, judged and punished Spartiates, declared war and peace, and supervised other officials (of whom Sparta had far fewer than Athens). The ephors themselves were virtually unchecked in their power—they only reported to their successors. Their special status was also underscored by their exemption from participating in communal syssitia and the privilege of having their own separate table.

Crisis of the Spartan Political System

The monolithic social structure of the ruling class, which had turned into a powerful military organization, contributed to Sparta's rapid rise among the Greek states. By the 5th century BCE, Sparta had established its hegemony over almost the entire Peloponnesus, leading the Peloponnesian League. However, the stagnation in social, economic, and political life, along with a spiritual decline— the price of domination over the helots—made Sparta a center of reaction in Greece. Meanwhile, victory in the Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) and the enormous tribute extracted from Athens sharply stimulated the processes of economic differentiation among the Spartiates and the development of commodity-money relations. These processes were further intensified at the beginning of the 4th century BCE when the giving and bequeathing of land parcels was permitted (although their sale was still officially prohibited, it likely occurred). The size of landholdings of the nobility increased through the acquisition of land (including from the helots) on the state's outskirts. The prohibition on trade began to be ignored.

The once ascetic Spartan way of life became a thing of the past. The mass impoverishment of ordinary Spartiates led to their loss of land allotments and, consequently, their full citizenship. The unity of the Spartan community disintegrated, and its military power declined— the number of full citizens decreased, and mercenaries began to appear. The loss of Messenia in the 4th century BCE, as a result of Macedonia’s conquest of Greece, along with a significant portion of land and helots, undermined the economic foundation of the Spartan state.

Attempts in the 3rd century BCE, at the behest of impoverished Spartiates, to restore the old order by redistributing land, abolishing debts, and reviving military power by granting citizenship to disenfranchised residents of Sparta, ended in failure. The objective laws of slave-owning society's development inexorably led to the collapse of the social and political orders that preserved the collectivist remnants of the communal system.

Ultimately weakened and torn by internal strife, Sparta, like all Greek states, fell under Roman control in the mid-2nd century BCE.

Related topics

Literature

- Andreev Yu. V. Men's unions in Dorian city-states (Sparta and Crete). St. Petersburg: Aleteya Publ., 2004. ISBN 5-89329-669-9.

- Berger A. Social movements in ancient Sparta, Moscow, 1936.

- Zaikov A.V. Society of ancient Sparta: main categories of social structure. Yekaterinburg: Ed. Ural State University, 2013.