Roman Roads

Since the beginning of the Republican period, Rome has paid significant attention to road construction. From the 4th century BC, Roman power extended to the northern and partially central regions of the Apennine Peninsula, while the fertile southern regions of Italy remained inaccessible. L.P. Kucherenko, in his work on the life and activities of Appius Claudius Caecus, notes that relations with Campania were unstable and depended on Roman military successes in this part of Italy. This created a need for the construction of stone or tile roads for the rapid movement of troops to distant areas from Rome. F.F. Velizhsky believes that Romans built roads to maintain trade and spiritual connections with the empire's center, Rome. R. Laurens also writes that roads facilitated the strengthening of economic ties between regions, claiming that the level of urban and agricultural development improved with the expansion of the road network in Italy. Moreover, we see the expansion of large estates owned by the Roman elite located far from Rome, indicating that the complex and branched road system contributed to the economic and trade growth. Ancient authors like Horace mention roads in their works, illustrating their use for travel and communication. Cicero, in his letters, reports using the Appian Way: "for I have decided to travel directly on the Appian Way to Rome." This shows that roads were also used by private individuals.

It is worth noting the existence of the imperial postal service, Cursus Publicus, which transmitted messages from the emperor to state officials and military commanders in the provinces. This organization covered the entire empire, and the right to use the state mail was confirmed by a "diploma" issued by the head of state. Pliny the Younger, in his letters to Trajan, discusses the validity of expired travel documents. Trajan replies that expired diplomas should not be in use and emphasizes the importance of sending new diplomas to all provinces promptly. Despite the above, the primary task of road construction was military necessity. L. Thompson believes that paved roads used by Roman legionaries were crucial for the mobility of the Roman army when moving from one area to another. Regular dirt or country roads did not allow quick movement, especially in rainy weather when roads were washed out. Therefore, stone road construction began in the 4th century BC.

Road construction, like urban planning in general, was overseen by censors. Livy indicates that the Senate funded construction projects, providing censors with credit for construction works. Censors also had general funds to start construction. Upon receiving funds, the nature of the work was not specified, and censors decided whether to spend the funds on new constructions or repairs. Military personnel or slaves directly handled the construction of paved roads.

The first mentions of the principles of Roman road construction are found in the ancient Roman law "The Laws of the Twelve Tables," dating back to 451-450 BC. Table VII states that "the width of the road in a straight direction was determined at 8 feet, and at turns - 16 feet." In later times, these dimensions were not strictly followed. From the 4th century BC, when roads gained strategic importance, they were laid as straight as possible without serving intermediate areas, as O. Choisy wrote in his work "History of Architecture." They only deviated from a straight path to avoid elevations. The paved part of the road was for fast communication, and since Roman horses were not shod, wide shoulders with natural ground were left on both sides for regular traffic. Roman builders carefully planned the route of future roads, and some modern highways still follow these routes (e.g., the section between Londinium and Verulamium, now Watling Street, which runs from Dover to Wroxeter).

Modern highways in Italy often run parallel to ancient ones. The most notable example is the modern route connecting Rome and Naples, with some sections running parallel to and near parts of the Appian Way. This road was the first with strategic significance for the conquest of southern Italy. Named after censor Appius Claudius Caecus, its construction began in 312 BC. According to L.P. Kucherenko, the construction started shortly after Capua attempted to secede from Rome. Rome sought to dominate Italy and needed to strengthen its presence in the peninsula's southern regions. R. Laurens believes that the Appian Way's construction was a strategic response to deteriorating relations with Italian peoples. The censor gave roads new significance, meeting the needs of the time. L.P. Kucherenko writes that Appius Claudius Caecus initiated the road's construction, which ran from Rome near Porta Capena through the Egeria Valley to Lake Albano and the ancient temple and grove of the goddess Diana in Aricia. It then crossed the Pontine Marshes to the sea at Tarracina and through the rich fields of Campania to Capua. Its length was 195 kilometers, extending to Brundisium - 570 km. The Appian Way soon became one of Italy's main highways, famed as the "queen of roads." Along it were aristocrats' tombs, like the tomb of the Scipios and the tomb of Cecilia Metella. Soon, Rome enveloped all of Italy with a network of roads: the Flaminian Way (connecting Rome and Ariminum), the Aemilian Way (connecting Piacenza and Rimini).

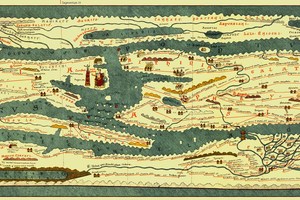

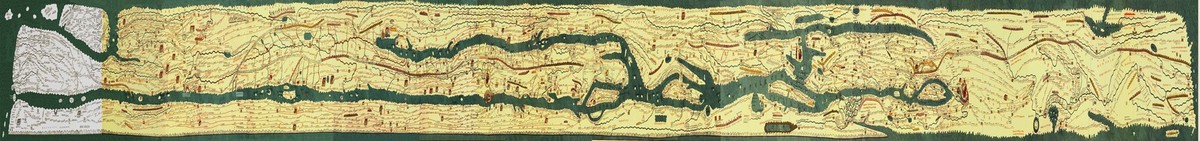

According to the Peutinger Table, 12 roads radiated from Rome, connecting major cities and sometimes merging, like the Aemilian Way reaching Rimini, and from there, the Flaminian Way to Rome. The phrase "All roads lead to Rome" has a real basis: a gilded milestone on the Roman Forum marked the starting point of all main roads in Italy. Thus, no matter the route, one would eventually reach Rome, giving rise to the famous saying.

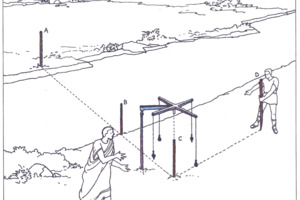

V.A. Kochetov provides a detailed description of the construction principles of Roman roads. He writes that the route was marked with two parallel ropes determining its width, a task handled by Roman surveyors - gromatici, specialists using an instrument called a groma. The groma, a vertical metal rod with a pointed lower end for sticking into the ground and a top end with a bracket and axis holding a horizontal crosspiece, had strings with weights hanging from each of the four ends. This instrument allowed surveyors to align stakes in a straight line, marking the future road's route. V.A. Kochetov believes that Roman roads in England deviated from their axis by no more than ½-¼ mile for every 20-30 miles of length.

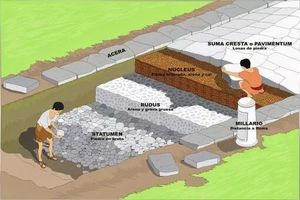

For Romans, it was crucial to make roads as straight as possible, as every turn would waste time during troop movements. Where necessary, elevated places were leveled, ravines filled, and bridges built. Besides straightness, the roads' durability was ensured by their multilayered and thick construction. V.A. Kochetov states that the total thickness of Roman roads ranged from 80 cm to 130 cm, with some sections reaching 240 cm. Roads consisted of four to five layers, with middle layers made of concrete. The bottom layer often consisted of stone slabs 20-30 cm thick, laid on well-compacted earth with a mortar bed and sand leveling. The second layer, 23 cm thick, was concrete (crushed stone set in mortar). The third layer, also 23 cm thick, was fine gravel concrete. Both concrete layers were thoroughly tamped.

Roads were usually designed by army engineers and built by legionaries, though during the Empire, many important roads were contracted to private builders employing slaves.

Roman pragmatism is evident in the efficient use of local materials for construction. Vitruvius noted that the economical use of materials and locations and moderate expenditure were essential. Most ancient constructions, whether temples, forums, or amphitheaters, were made from materials sourced nearby, easing the task for builders and reducing transport costs for clients. G.I. Sokolov writes that the section of the Appian Way near Rome is paved with tuff, found near Rome and Naples. In the Ariccia Valley, the road spans 197 meters on a local peperino stone wall, 11 meters high, with three arches for mountain streams. Other sections use volcanic lava slabs. These materials' volcanic origin is due to the proximity of Mount Vesuvius. The varying materials and road directions were aimed at high quality and long-lasting constructions. Drainage ditches on both sides of the roads prevented puddles, and roads were regularly maintained.

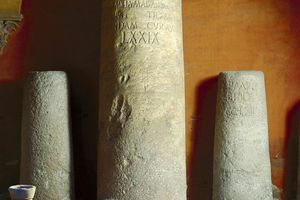

Such meticulous work yielded positive results. L. Thompson writes that armies could cover up to 25 miles daily, even in adverse weather, while carrying full gear on foot. Using horses, as the Cursus Publicus did, increased speed to 50-60 miles daily, enabling swift transmission of urgent messages from the emperor to officials and commanders. O. Choisy notes that roads had buildings for horse changes and, due to the scarcity of inns, staging posts for overnight stays ("mansiones"). Cylindrical milestones indicated distances to the nearest town and the emperor's name during whose reign the road was built or repaired, enhancing travel speed.

T. Mommsen remarked that following Claudius' example, the Roman Senate enveloped Italy with a network of roads and fortresses crucial for military hegemony. Roads indeed allowed control over vast territories, facilitated provincial Romanization, and promoted economic ties.

The Peytinger table. lat. Tabula Peutingeriana. A parchment copy of ancient Roman map, which were made by a monk from Colmar (Alsace) in the 13th century. The map is 6.75 m long and 0.34 m wide.It has in keeping in the Austrian National Library in Hofburg (Vienna).

The Peytinger table. lat. Tabula Peutingeriana. A parchment copy of ancient Roman map, which were made by a monk from Colmar (Alsace) in the 13th century. The map is 6.75 m long and 0.34 m wide.It has in keeping in the Austrian National Library in Hofburg (Vienna).

Literature

1) ROMAN ROADS CONSTRUCTION TECHNOLOGY AND USE IN REGIONS DURING THE REPUBLIC AND EARLY EMPIRE. pdf

2) Life of the Greeks and Romans-Velishsky.pdf

3) Vitruvius. X books of Architecture / translated from Latin by F. A. Petrovsky, Moscow: Librocom, 2012, 317 p.

4) Horace Quint. Satires. [electronic resource]. URL: http://e-libra.ru/read/87549-satiry.html (accessed: 15.01.2017).

5) Roads in ancient Rome. [electronic resource]. URL: http://www.historie.ru/civilizacii/rimskaya-imperiya/96-dorogi-v-drevnem-rime.html (дата обращения: 15.01.2017).

6) Kochetov V. A. Roman concrete, Moscow: Stroyizdat Publ., 1991.

7) Kucherenko L. P. Appius Claudius Caecus: personality and politician in the context of Roman era. Syktyvkar: IPO Syktyvkar State University, 2008.

8) Roman censors and urban planning in Italy-Kucherenko. pdf

9) Mommsen T. The History of Rome: in 3 volumes St. Petersburg: Juventa, Nauka, 1994. Vol. 1.

10) Letters of Marcus Tullius Cicero to Atticus, relatives, brother Quintus, M. Brutus. [electronic resource]. URL: http://ancientrome.ru/antlitr/t.htm?a=1345960000 (accessed: 15.01.2017).

11) The Letters of Pliny the Younger. Panegyric to Trajan. [electronic resource]. URL: http://librebook.ru/pisma_pliniia_mladshego__panegirik_traianu (дата обращения 15.01.2017).

12) Modern map of Great Britain. [electronic resource]. URL: https://yandex.ru/maps/?ll=0.602518%2C51.173805&z=9 (accessed 15.01.2017).

13) Sokolov G. I. Roman ancient art. [The Art of ancient Rome]. Series: "Essays on the history and theory of fine arts", Moscow: Iskusstvo Publ., 1971, 232 p.

14) Titus Livy. The history of Rome from the foundation of the city. [electronic resource]. URL: http://ancientrome.ru/antlitr/t.htm?a=1364000100 (accessed 15.01.2017).

15) Chrestomathy of history of slate and law. Moscow: Norma, 2010, vol. 1.

16) Shirokova N. S. Roman Britain: Essays on the history of Historical and Cultural Monuments. [Roman Britain: essays on History and Culture]. Saint Petersburg: Humanitarian Academy Publ., 2016.

17) Choisy O. History of Architecture [History of Architecture], translated from French by V. D. Blavatsky, Moscow: V. Shevchuk, 2005, vol. 1.

18) The Roads of Roman Italy Mobility-Ray Laurence.pdf

19) Tabula peutingeriana. [electronic resource]. URL: http://www.tabula-peutingeriana.de/ (accessed 15.01.2017).

20) Thompson L. Roman roads // History Today. Feb 1997. Vol 47. Issue 2. P. 21-28.