Jugurthine War

The Jugurthine War (Latin: Bellum Iugurthinum) was an armed conflict between Ancient Rome and the Numidian King Jugurtha, lasting from 112 to 105 BC. Jugurtha's successful use of bribery and corruption tactics exposed the moral decay among the Roman elite. The most detailed account of this war was written by the Roman historian Sallust, who viewed it in the context of the decline of Roman virtue.

Jugurtha (160–104 BC) was the King of Numidia from 117 to 105 BC, the son of King Mastanabal, and the grandson of Masinissa, who waged the Jugurthine War against Rome.

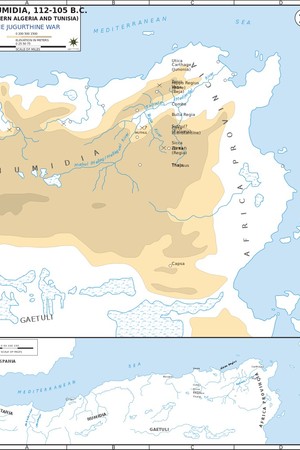

Numidia was a state that existed from the 3rd to the 1st century BC in North Africa (covering parts of modern-day northern Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya). The Berber tribes living there were referred to as Numidians by the Greeks and Romans. Rome eventually conquered Numidia in 46 BC, turning it into one of its provinces.

Before the formation of a unified state in the 3rd century BC, the Numidians were nomads. They briefly united into a single state with the capital at Cirta (now the city of Constantine in Algeria), but it later split into two parts: Western and Eastern Numidia. Both parts fought against Carthage, which sought to subjugate them. King Masinissa of Eastern Numidia managed to defeat Carthage and unify Numidia into a single state in 202 BC with Roman assistance.

Masinissa is considered the first king of a unified Numidia, ruling from 202 to 149 BC. He gained fame as an ally of Rome in the Battle of Zama in 202 BC, fighting against the Carthaginian general Hannibal during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC). Rome helped Masinissa unite Numidia into a single state, making him its ruler with the status of a Roman ally.

Background

After his father's death, Jugurtha was raised by his uncle Micipsa, the next ruler of Numidia, who had two sons of his own, Adherbal and Hiempsal. Jugurtha was so popular among the Numidians that Micipsa tried to get rid of him by sending him to aid Scipio Aemilianus, who was besieging Numantia at the time. Jugurtha managed to convince the Roman senators of his loyalty, and under their pressure, Micipsa adopted Jugurtha. Before his death, Micipsa divided Numidia into three parts, but after his death in 118 BC, Jugurtha claimed the right to sole rule and began fighting his brothers.

As a result, he killed Hiempsal in 117 BC, and forced Adherbal to flee to Rome for protection in 116 BC, as Numidia held the status of a Roman ally and the Roman Senate had the final say in the dispute between the two brothers for the Numidian throne. Following his brother, Jugurtha also arrived in Rome with an embassy. Eventually, a senatorial commission divided Numidia in such a way that Jugurtha received the less developed western part of the country, where nomads, considered good warriors, lived, while Adherbal received the eastern part.

Beginning of the War

Four years later, in 112 BC, Jugurtha again attacked Adherbal, who sought help from Rome. At that time, Rome decided to assist him diplomatically, which proved unsuccessful, and Rome was not yet able to resolve the issue by military means, as it faced a military threat from the Germans. As a result, Jugurtha captured the capital of Numidia, Cirta.

After taking the capital, Jugurtha killed not only Adherbal, who held the title of Friend and Ally of the Roman People, but also Roman citizens who had participated in the defense of the capital. In response, the Senate declared war on Jugurtha, which became known as the Jugurthine War. One of the main and detailed sources on this war is the book The Jugurthine War by the ancient Roman historian Sallust, who examined the war in the context of the decline of Roman virtue in favor of bribery and corruption.

Given Numidia's proximity to the Roman province of Africa, the consuls of 111 BC were given control over both Italy and Africa, meaning war with Numidia, and whoever managed the province of Africa would also command all Roman military forces in the upcoming war.

Coin of Numidia from the reign of King Jugurtha, minted around 110 BC.

Coin of Numidia from the reign of King Jugurtha, minted around 110 BC.

Main Events of the Jugurthine War

At this time, an embassy from Jugurtha arrived in Rome to seek a peaceful resolution, but the Senate refused to receive it, and the embassy returned to Numidia empty-handed. One of the consuls of 111 BC, Lucius Calpurnius Bestia, was tasked with initiating the war. One of his legates was Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, who had led the Senate's embassy to Jugurtha in 112 BC, attempting to resolve the dispute between Jugurtha and his brother peacefully, but the embassy had failed.

Bestia captured several towns in Numidia and then made peace with Jugurtha, as the threat from the Germans in the west required significant forces, and Jugurtha himself was a formidable opponent. Rome was not yet in a position to fight two strong adversaries on two fronts.

Although rumors began to circulate in Rome that Bestia had been bribed by Jugurtha, his peace agreement was not ratified by the Senate. Jugurtha, in order to strengthen his power and fight against a newly emerged rival for power in Numidia, the grandson of Masinissa, the son of Gulussa, Massiva, arrived in Rome. Both Jugurtha and Massiva arrived in Rome to settle the issue of power, and Jugurtha needed to answer for the legality of the peace agreement between Rome and Numidia.

In the end, Jugurtha was not allowed to speak in the popular assembly, and Massiva was killed in Rome, likely on Jugurtha's secret orders, forcing Jugurtha to flee Rome, famously saying as he fled: "O venal city, you will perish soon, once you find a buyer." Ancient authors provide conflicting information about the circumstances of Jugurtha's departure from Rome. The Roman historian Livy reported that Jugurtha secretly fled from Rome, while his colleague, also a Roman historian, Sallust, reported that Jugurtha left Italy by order of the Roman Senate.

As a result, the war between Rome and Numidia resumed, and the new commander of the Roman forces was one of the consuls of 110 BC, Spurius Postumius Albinus. Albinus intended to defeat Jugurtha in a single campaign and conclude peace with him in time for the next elections in the capital. But Jugurtha delayed the war as much as possible, and failing to defeat Jugurtha before the elections, Albinus left for them, leaving his brother Aulus Postumius Albinus in command of the forces.

Jugurtha took advantage of this situation, launching a night attack on the Roman camp and defeating the Romans. He forced the Romans to "pass under the yoke," humiliating them mortally, and then imposed a peace agreement on Aulus, which stipulated that all Roman forces must leave Numidia within ten days. Rome refused to ratify this agreement, as it had done with Bestia's treaty, and decided to continue the war despite the defeat. The new commander of the Roman forces was one of the consuls of 109 BC, Quintus Caecilius Metellus, known for his honesty and incorruptibility.

Numidian horseman.

Numidian horseman.

Metellus successfully began the war, reorganizing the Roman army in the region and reinforcing it with fresh troops from Rome. He invaded Numidia and inflicted several defeats on Jugurtha and his commanders. Jugurtha attempted to negotiate peace with Metellus.

Metellus did not reject the negotiations but conducted them while persuading Numidian envoys to hand over Jugurtha, dead or alive, to him, all the while continuing his advance into Numidia. Ultimately, in the winter of 109–108 BC, after a series of battles won by the Romans, failed negotiations, and the devastation of Numidia's territory, Metellus withdrew to the Roman province of Africa, leaving Roman garrisons in key Numidian cities.

During the winter, Jugurtha resumed negotiations but refused to surrender, and the war resumed with the arrival of spring. Metellus again invaded Numidian territory and launched an offensive on the city of Thala, located in the desert, where Jugurtha was hiding with his family. However, Jugurtha fled the city at night before the Romans arrived, crossing the desert to reach his father-in-law, the King of Mauretania, Bocchus (who ruled from 118 to 91 BC), whom he persuaded to join his side in the war against Rome.

Bocchus supported Jugurtha, providing him with troops, and the war continued. Metellus attempted to drive a wedge between the allies and began peace negotiations with Bocchus, but was unable to conclude them or end the war, as one of the newly elected consuls of 107 BC was assigned the province of Africa by popular vote, thus taking command of the war.

This consul was Gaius Marius, a former subordinate of Metellus. Metellus was recalled to Rome. Although Metellus did not finish the war, he was awarded the agnomen (a nickname or surname) "Numidicus" for his successes in it.

Gaius Marius arrived in Numidia with reinforcements, allowing him to strengthen his forces and launch an offensive against Jugurtha and his ally, Bocchus. Marius repeatedly defeated Jugurtha's forces and their allies, forcing Jugurtha to turn to Bocchus for help and protection.

At this time, the Roman envoy Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Marius's subordinate, managed to persuade Bocchus to betray Jugurtha. As a result, Jugurtha, who arrived at Bocchus's court to discuss further joint actions against Rome, was seized and handed over to the Romans. Jugurtha's betrayal took place in December 106 BC, and he was brought to Rome, where he was paraded in Marius's triumph and later executed.

The capture of Jugurtha marked the end of the Jugurthine War in early 105 BC. As a result, Numidia retained its independence as a Roman ally, but under the rule of Bocchus. As a reward for his loyalty, Bocchus received the western part of Numidia. In addition, Jugurtha's kingdom was further divided between Gauda, the brother of Jugurtha's adoptive father Micipsa, who became the king of Numidia.

Denarius depicting the capture of Numidian King Jugurtha by Sulla, minted by Faustus Sulla, son of L.C. Sulla, in 56 BC. It is likely that the reverse of the denarius shows an image copied from Sulla's signet ring, which he commissioned after the conclusion of the Jugurthine War. Sulla is depicted in the center, seated on a chair. To his left is a kneeling figure of the Mauretanian king Bocchus, and on the other side is the bound Jugurtha.

Denarius depicting the capture of Numidian King Jugurtha by Sulla, minted by Faustus Sulla, son of L.C. Sulla, in 56 BC. It is likely that the reverse of the denarius shows an image copied from Sulla's signet ring, which he commissioned after the conclusion of the Jugurthine War. Sulla is depicted in the center, seated on a chair. To his left is a kneeling figure of the Mauretanian king Bocchus, and on the other side is the bound Jugurtha.

Results of the war

The Roman historian Sallust, who wrote the history of the Jugurthine War in the 1st century BC, emphasizes Jugurtha's skillful use of bribery and corruption to influence the Roman Senate, shedding light on the moral decay among the Roman elite. Sallust's account portrays Jugurtha as a cunning and resourceful leader, who exploited the weaknesses of the Roman political system to his advantage.

The war also had significant consequences for the Roman military and political landscape. It exposed the inefficiency and corruption within the Roman military command and the Senate, leading to reforms that aimed to address these issues. The Jugurthine War is often seen as a prelude to the larger conflicts and civil wars that would eventually lead to the fall of the Roman Republic and the rise of the Roman Empire.

Related topics

Literature

1. Gaius Sallust Crispus. The Catilina Conspiracy and the Yugurta War, Moscow, 1916.

2. Titus Livy. Essays. In 2 vols. - (Series "Literary monuments"). - L.: Science, 1969. - Vol. 1. Annals. Small works. - 444 p.; Vol. 2. History. — 370 pages.

3. Durov V. S. Art historiography of Ancient Rome. St. Petersburg: SPbU Publ., 1993.

4. L. Muller. Numismatics of Ancient Africa, 1862, vol. III. From .1-77.

5. F. Lubker. Iugurta / / Realy slovar ' klassicheskikh drevnostey po Lyubkeru [Real dictionary of classical Antiquities by Lubker], edited by F. F. Zelinsky, A. I. Georgievsky, M. S. Kutorga et al. Society of Classical Philology and Pedagogy, 1885, pp. 687-689.