Catilina Conspiracy

The Conspiracy of Catiline (Latin: Coniuratio Catilinae; Bellum Catilinae) was an attempt by a faction of the Roman nobility to seize power through an armed uprising. The event is named after its organizer, Lucius Sergius Catilina. During the 60s BCE, there were two conspiracies, the most well-known of which is the later one.

Sources provide fragmented information about the existence of the "first conspiracy of Catiline," which is dated to 66–65 BCE. The historical authenticity of this "first conspiracy" is not universally accepted by historians, and its details remain unclear. The main events of Catiline's conspiracy took place later, in 63 BCE. In the second half of that year, after the noble-born Lucius Sergius Catilina was defeated in the consular elections, a number of Roman nobles allegedly gathered around him with the aim of seizing power. Catiline's demand for the cancellation of debts attracted not only some indebted nobles but also thousands of impoverished farmers and veterans to his side. The primary sources that recount the "second conspiracy"—chiefly Cicero and Gaius Sallustius Crispus—are hostile towards Catiline and sometimes contradict each other, making it difficult to reconstruct the events of 63 BCE. The inherently secretive nature of the conspiracy (if it indeed existed) also complicates the historical reconstruction.

The "attempted coup" was uncovered and suppressed; five active participants were executed without trial by special decision of the Senate. Catiline, who fled from the capital, led rebel forces in Etruria and died in battle against the government army. The suppression of the conspiracy was used by Cicero to establish himself as one of the informal political leaders of Rome. From antiquity onward, Catiline and his attempted coup were viewed extremely negatively, but from the mid-19th century, a new image of him as an idealistic revolutionary began to emerge.

The First Conspiracy

For a long time, it was widely believed that in late 66 or early 65 BCE, the patrician Lucius Sergius Catilina was involved in a failed attempt to seize power (these events are known in historiography as the "first conspiracy of Catiline"). However, starting from the 20th century, the plausibility of these events has increasingly been questioned by scholars (see the end of the section).

In 68 BCE, Catiline reached the office of praetor, after which he was appointed governor of the province of Africa with the rank of propraetor. In 66 BCE, upon returning to Rome, he attempted to run for consul for the following year, the pinnacle of a Roman politician's career. However, Consul Lucius Volcatius Tullus barred Sergius from the elections due to an ongoing trial against him for extortion and abuse of power in his province. As a result, according to some sources, Catiline attempted to seize power. Another reason for the organization of the first conspiracy was the removal of the elected consuls for 65 BCE, Publius Autronius Paetus and Publius Cornelius Sulla, due to mass bribery of voters. Seeking to reclaim his purchased office, Paetus plotted to seize consular power through a conspiracy. Other participants in the conspiracy mentioned by sources include the young noble Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso and the unelected consul Publius Sulla.

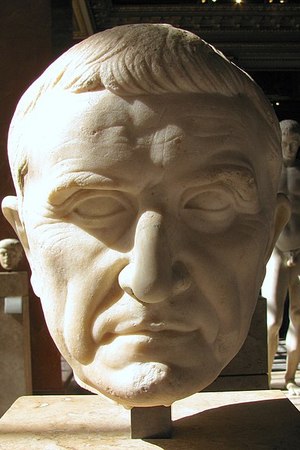

Some sources also name or even identify as instigators of the "first conspiracy" the wealthiest man in Rome, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and the ambitious politician Gaius Julius Caesar. It was claimed that, as a result of the coup, Crassus was to become dictator and Caesar the master of the horse. However, the primary source of this information is Suetonius, who is not very reliable; he drew upon the writings of Caesar's opponents when recounting these events. After the conspiracy of 63 BCE was uncovered, many politicians accused their opponents of past connections with Catiline, which influenced all reports of the events of 66-65 BCE. Cicero and Sallust, contemporaries of the described events, are silent on the participation of Crassus and Caesar in the first conspiracy. Some scholars have also suggested that Gnaeus Pompeius might have been involved in the secret alliance.

According to Sallust, the conspirators planned to kill both consuls (Lucius Aurelius Cotta and Lucius Manlius Torquatus) on the day they took office (January 1, 65 BCE), hand over the symbols of their authority—the consular fasces—to Paetus and Catiline (or, in another version, to Paetus and Sulla), and give Piso an army to send him to Spain. According to the Roman historian, their plot failed, but the members of the secret agreement postponed their uprising to early February, hoping to kill not only the consuls but also several senators. Sallust explains the conspiracy’s failure by Sergius' haste: he gave the signal to start the massacre before their armed supporters had gathered. Suetonius’ version differs significantly: he does not mention Catiline in connection with the first conspiracy and includes Crassus, Caesar, Paetus, and Publius Sulla among its leaders. Crassus was to become dictator, Caesar the master of the horse, and Autronius Paetus and Publius Sulla were to become consuls after Crassus relinquished his extraordinary powers. However, according to Suetonius, the conspiracy was uncovered before Caesar took office as aedile (January 1, 65 BCE). Citing his sources, Suetonius also provides reasons for the failed coup: Crassus’ absence from the forum on the day of the uprising and Caesar's failure to give the signal to start the revolt. Although information about the first conspiracy became known to many Romans, a Senate investigation was never initiated due to the veto of one of the tribunes. The Senate limited itself to providing the consuls with an armed guard, while Piso, one of the members of the secret alliance, was sent to Nearer Spain with the powers of a propraetor, even though he had only reached the junior position of quaestor.

The accounts of the first conspiracy in sources contain several contradictions and inaccuracies. For instance, some details in Sallust’s version seem implausible: the very possibility of a coup organized by a very small group of debtors and marginal nobles is questioned, as is the possibility of seizing power through the assassination of the consuls. Another contradiction in the events of 66–65 BCE is the apparent lack of interest on Catiline’s part in participating in the uprising, as well as Cicero’s silence, despite his vested interest in publicizing these events (he only mentions the first conspiracy in passing and without details). There are two main views in historiography regarding the reality of this attempted coup—some historians deny the existence of the first conspiracy, while others believe in its historicity and attempt to explain the existing contradictions in the sources. A significant fact for interpreting the first conspiracy is the absence of any punishment for its participants. Some researchers (notably F. Jones, E. Salmon, and H. Scullard) believe that the lack of punishment was due to the intervention of influential patrons of Catiline and his allies, often pointing to possible involvement by Crassus. Other historians (notably S. L. Utchenko) see the lack of punishment as evidence of the insignificance of the events, as well as the exaggeration of their importance and the introduction of fictional details by later authors. Since the mid-20th century, it has often been suggested that the first conspiracy never existed at all. E. Grün cautiously notes that the existence of anything that could be qualified as a "conspiracy" remains doubtful and calls for restraint in speculating when researching these events.

The Conspiracy of 63 BCE

In 64 BCE, after being acquitted in a trial for abuse of power in Africa, Catiline ran for consul. He faced a new prosecution as the Senate began to hold the executors of the proscriptions accountable, but the court’s presiding officer, Gaius Julius Caesar, unexpectedly secured Sergius’ acquittal. Catiline had a good chance of winning the election alongside Gaius Antonius Hybrida, and they worked together against Cicero, the third strong candidate, arguing that he should not hold the highest magistracy due to his low birth (he was half-derisively called homo novus). In response, Cicero publicly reminded the people of his opponents’ dark pasts, particularly that of Catiline. As a result of Cicero’s vigorous election campaign, Sergius lost, and Cicero was elected consul; Antonius became the second consul. Sallust dates the beginning of the "new conspiracy" to 64 BCE, but modern scholars suggest that the Roman historian was mistaken by a year.

Background and Causes of the Conspiracy

The most significant precondition for the conspiracy was the complex economic situation in Italy. Economic and social problems had existed for some time, but the economic situation worsened in 63 BCE. A year earlier, Gnaeus Pompey the Great had concluded the Third Mithridatic War, through which the Romans regained control of the wealthy province of Asia and annexed new territories (primarily Syria and part of Mithridates Eupator’s Pontic Kingdom). Prior to this, Pompey had destroyed the main pirate bases that had severely damaged maritime trade. Since investments in the East were more profitable for many financiers than operations in Italy, they began transferring their capital to the eastern provinces, which had previously been inaccessible due to wars and pirates. Previously, creditors preferred not to disturb large debtors in Italy; on the contrary, in the absence of more profitable investment opportunities, they preferred to wait for substantial interest to accumulate in addition to the principal debt. After Pompey’s victories and the opening of the Asian market, creditors began demanding the repayment of debts from Italian debtors to invest in more profitable eastern ventures. In Italy, interest rates began to fluctuate rapidly, and financiers started investing only in reliable and consistently profitable enterprises. To curb the outflow of capital to the eastern provinces, the Senate was forced to temporarily ban the export of gold and silver from Italy in 63 BCE. At the same time, the mid-1st century BCE was marked by enormous expenditures by individual senators on luxury items (for example, it was during this period that Lucullus’ legendary feasts were held) and on election bribes. Finally, the 60s BCE saw widespread discontent directed against wealthy Romans from the equestrian order. In this context, Catiline’s campaign promise to cancel debts, made during the consular elections, gained widespread support.

The conspiracy also had political causes, including increased competition among candidates for magistracies during elections and the exclusion of 64 people from the Senate by the censors in 70 BCE. Catiline himself was driven to organize the conspiracy by unfulfilled personal ambitions that he could not achieve through legal means. Various researchers speculate that the conspiracy leader had no far-reaching goals beyond seizing power, or that his primary interest was personal enrichment or even support for reforms in favor of small and landless farmers. Unfulfilled personal ambitions also motivated many noble Romans to prepare for the coup. The main sources of information about the conspirators, Sallust and Cicero, depict them as society’s outcasts, but in reality, the social base of the rebels was much broader. Among the conspirators were many nobles, including the former consul Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, who had been expelled from the Senate by the censors for “immorality.” Lentulus may have been driven to join the secret organization by the prophecy of the Sibyl that foretold three Romans from the Cornelius family would rule Rome. The first two were traditionally considered to be the four-time consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna and the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla. T. A. Bobrovnikova presents a different version of the legend: the Sibyl supposedly predicted power for three people whose names began with the letter “C” (Latin “C”). Other nobles in Catiline’s circle, on the other hand, failed to reach the high offices their ancestors had held and hoped to attain these magistracies through a seizure of power. Similar goals were pursued by some members of the wealthy but politically under-involved equestrian order. The secret alliance also attracted many representatives of Rome’s “golden youth,” who rejected the traditional career path (cursus honorum). A significant number of large debtors were drawn in by the promise of debt cancellation. Catiline himself is often considered a debtor. According to some accounts, he was even bankrupt; however, Sallust notes that during the preparations for the armed uprising, he was still able to borrow substantial sums to organize armed detachments, which would have been impossible if he were bankrupt. There is no consensus on the involvement of Crassus and Caesar in the second conspiracy. The theory of their support for Catiline during the elections seems more likely to historians, but the lack of motivation to participate in the conspiracy is noted. Later, Crassus helped expose the conspiracy, and Caesar voted for life imprisonment as a punishment, agreeing on the conspirators' guilt (see the section “Gathering Evidence, Investigation, Execution” below). There is also no consensus on the involvement of the second consul, Gaius Antonius Hybrida, though he is more often considered to have been informed, sympathetic, or directly involved in the conspiracy.

The aforementioned economic causes ensured significant support for radical slogans on the Italian Peninsula. Catiline’s supporters were actively backed by the population of Etruria, Picenum, and some towns in central and southern Italy (notably Terracina and Croton); they may also have had support in Apulia. The conspirators were actively supported primarily by Sulla’s veterans, who had been settled throughout Italy by the dictator after his victory in the civil war. Sergius’ radical program also resonated with some farmers from Etruria, whose land Sulla had given to these same veterans. The reasons that drove Sulla’s veterans to extreme measures include their inability or unwillingness to cultivate their plots (this view is criticized—many of the veterans were originally from farming backgrounds) or the fact that many of the 120,000 veterans had received infertile land that could not support profitable farming. Many residents of Etruria had lost their plots due to debts; others retained their land but were still heavily indebted. According to Sallust, it was precisely their debts that pushed these people to take up arms on Catiline’s side. Dio Cassius mentions Sergius’ land law proposal, but modern historians find it difficult to determine the accuracy of this late historian’s account. Although Catiline and many of his supporters had previously backed Sulla, the conspirators also included the children of the dictator’s proscription victims: the Senate still refused to rehabilitate them and restore their full political rights. In addition to promises of debt cancellation, farmers were promised relief from the tyranny of Roman magistrates. Shortly before the events of 63 BCE, Tribune Publius Servilius Rullus proposed a fairly radical bill aimed primarily at providing land to large numbers of landless farmers and urban poor, though without expropriations. Some researchers (notably R. Y. Wipper) see a direct connection between the failure of Rullus’ bill and Catiline’s conspiracy. Under the assumption of a connection between Rullus and Catiline, it is also possible to consider the existence of a “revolutionary general staff” (as T. A. Bobrovnikova puts it) composed of Crassus and Caesar, who allegedly directed all of their actions.

The conspirators also counted on the support of the Roman urban population. The latter were dissatisfied with high housing rents, poor living conditions, high unemployment, the suspension of colonial projects, and the cessation of land distributions from the state-owned ager publicus. However, the expected support from the urban plebs did not materialize: in the event of turmoil, their property and lives were at risk, so they welcomed the suppression of the conspiracy. H. Scullard notes that Catiline’s excessively radical program alienated not only many senators but also most equestrians, small traders, and ordinary workers.

Although sources mention plans to involve slaves in the uprising, the nature of these accounts is very vague. Moreover, there was no consensus among the conspirators on this issue: Lentulus was the most active in this regard, but Catiline’s generous promises were directed only at citizens. Since the leaders of the secret alliance did not advocate for the reform of the slaveholding system (E. Grün characterizes Sergius’ goal as a political coup, not a social revolution), slaves had no reason to join the underground movement en masse. C. Yavetz believes that Lentulus’ promises were driven by the conspirators’ need for soldiers, but certainly not by a desire to drastically revise the slaveholding system. Nevertheless, rumors of a general emancipation of slaves spread widely. Many slaves, including fugitives from their masters (fugitivi in Latin), made contact with the conspirators on their own initiative, resulting in Catiline’s forces being bolstered by a significant number of runaway slaves. Moreover, after Lentulus’ arrest, slaves in Rome attempted to free him. On the other hand, Cicero counted among his supporters in the fight against the conspiracy some slaves who lived in relatively decent conditions: P. F. Preobrazhensky identifies them as domestic slaves.

In addition to relying on the discontented population of Rome and Italy, the conspirators hoped that the uprising would be supported in the provinces, particularly in Africa. They also negotiated with some tribes allied to Rome—in particular, the Allobroges: the population of Narbonese (Transalpine) Gaul, where the Allobroges lived, suffered not only from debts but also from Roman governors who oversaw debt obligations and plundered the province. For a time, Catiline also hoped for Piso’s uprising in Nearer Spain, but he soon died and could not join the rebellion.

The Beginning of the Conspiracy

After losing the elections to Cicero and Antony, Catiline ran again in the next year's consul elections. The exact date of these elections is unknown: they were held either in July, as usual, or later, in September or even October of 63 BC. Shortly before the vote, a new law against electoral violations (lex Tullia de ambitu) was passed at Cicero's initiative, aimed primarily against Catiline, who often resorted to bribery. During the campaign, Catiline openly spoke about his dire financial situation, claiming that only someone like him—burdened with enormous debts—could truly defend the interests of the poor. To attract more supporters, he put forward the slogan of complete debt cancellation (tabulae novae—“new tablets”). It is possible that Caesar and Crassus supported Sergius during the elections. Crassus's involvement might have been direct, as he was one of the main creditors of promising politicians, lending them money for election campaigns. However, the senior magistrates were elected in the centuriate comitia, where the votes of wealthy citizens were decisive, and the consuls elected were Decimus Junius Silanus and Lucius Licinius Murena.

Despairing of achieving the consulship by legal means, Catiline fully resorted to violent methods to achieve his career goals. Sources differ in their accounts of when the secret agreement between Sergius and other desperate aristocrats took place, but they do provide some details about the process. For instance, they mention a ritual in which the conspirators drank wine mixed with human blood. Plutarch even reports that the conspirators sealed their oath with a ritual murder and the consumption of the victim’s flesh, while Dio Cassius claims that a child was sacrificed. Some researchers interpret this as evidence of a ritual from some "demonic Eastern religion," although many deny the historical accuracy of this episode, viewing these accounts as later propaganda. Additionally, the secretive nature of the oaths raised concerns among contemporaries: traditionally, oaths in Ancient Rome were made publicly.

The sequence of events during the conspiracy's formation and their dating remain uncertain. The dating of the consul elections to the summer months is not universally accepted; some suggest that the elections were postponed (possibly more than once), leading to their dating to October 20, 21, 28, or even November 4. T. Mommsen dates not only the consul elections to October 63 BC but also the final formation of the secret alliance. S. L. Utchenko believes that the conspiracy formed in the summer, but before the consul elections. Sallust, however, erroneously dates the formation of the conspiracy to 64 BC, adding further confusion.

The conspirators planned their main actions for late October, a point on which both proponents of summer elections and those advocating autumn elections agree. It was expected that the conspirators would launch an uprising in the capital, kill their opponents, Sergius’s supporters would start rebellions in various Italian cities, and Gaius Manlius would lead a major uprising in Etruria (according to another version, Manlius acted independently; see below). The uprising was scheduled for October 28. Catiline promised to cancel all existing debts, carry out new proscriptions, and distribute the main magistracies among all active participants (with the leader of the conspiracy finally becoming consul himself). The conspirators did not have far-reaching plans for reforming the state structure and social institutions (at least, no evidence of such plans has survived). Some researchers (notably G. M. Livshits) doubt that Catiline seriously intended to implement the economic program he had announced during the elections and that had drawn attention to him—arguing that it might have been used only to attract impoverished veterans and peasants. The possibility of carrying out agrarian reform is also disputed (see above, "Causes. Social Base of the Conspiracy").

There is also a version in historiography that Catiline was not the organizer and active participant of the conspiracy's first phase but joined it later during the armed uprising. According to this version, proposed by K. H. Waters and Robin Seager, the story of his active involvement was fabricated and widely disseminated by Cicero. In this version, Gaius Manlius becomes the central figure of the entire movement; he supported Catiline in the consul elections and, after the failure, began preparing an armed uprising in Etruria. However, this version is based on a large number of implausible assumptions, raising skepticism about its validity.

Joseph-Marie Vien, "The Oath of Catiline." Late 18th century, Casa Martelli, Florence. The painting depicts the ritual oath that sealed the conspiracy.

Joseph-Marie Vien, "The Oath of Catiline." Late 18th century, Casa Martelli, Florence. The painting depicts the ritual oath that sealed the conspiracy.

The Unveiling of the Conspiracy

Initially, the conspiracy’s success relied heavily on the element of surprise, but this advantage was lost due to numerous information leaks. The diverse social composition of the conspirators created significant challenges in organizing and coordinating their actions. Rumors of a secret plot spread widely in Rome, yet no one had concrete evidence. The senators took no action for a long time, as they lacked solid proof of the conspiracy.

In mid-October, three influential Romans—Crassus, Marcellus, and Metellus Scipio—received anonymous letters warning of the impending conspiracy, which they immediately brought to Cicero. The consul asked the recipients to read the letters aloud at a Senate meeting the next morning as evidence of the looming threat. Confirming the rumors, Cicero persuaded the senators to send the troops awaiting a triumph outside the city walls to Apulia and Etruria and to pass an emergency decree (senatus consultum ultimum). The exact chronology of these events is reconstructed with some discrepancies: for example, E. Salmon dates the delivery of the letters to Cicero to the evening of October 18, while P. Grimal places it on the evening of October 20; T. Mommsen, in his Roman History, dates the Senate session with the reading of the letters and the accusation against Catiline to October 20, while P. Grimal dates it to October 21. Some modern researchers doubt the authenticity of the letters received by Crassus, attributing their forgery to Cicero. According to this hypothesis, the consul not only hoped to sway doubtful senators with the forged letters but also to gauge Crassus’s stance on the conspiracy (as Crassus would not have delivered the letters to Cicero if he were complicit). Due to the conspiracy’s exposure, the members of the secret alliance in the capital were forced to postpone their plans, but Manlius still launched his revolt at the end of October. The beginning of the uprising in Etruria significantly strengthened Cicero’s position: whereas previously, the consul’s warnings had been met with skepticism due to his bias against Catiline and unfulfilled predictions of an imminent uprising in the capital, Manlius’s actual rebellion forced the senators to take his words more seriously. Cicero also mentioned Catiline’s failed plans to seize Praeneste on November 1, an important fortress near Rome, although this report is considered improbable.

The lack of indisputable evidence prevented the Senate from bringing a successful prosecution against Catiline, so they limited themselves to launching an investigation. Nevertheless, Lucius Aemilius Paulus brought formal charges against him (this happened on November 1 or 2). Sergius responded that he was willing to remain in Rome under house arrest at the home of the praetor Metellus Celer or the consul until the trial, but they refused. After this, Catiline agreed to voluntary house arrest (apparently, the conspiracy’s organizer needed time to complete preparations and decided to participate in the upcoming trial). However, on the night of November 6, a secret meeting of the Catilinarian conspirators was held at Laeca’s house on the Street of the Fullers, where they decided to kill Cicero the following morning. Additionally, they revised their plans: according to ancient sources, they now planned to set the city on fire (allegedly, they intended to divide the capital into twelve or even a hundred sections where fires would simultaneously break out, and they planned to damage the aqueduct system to complicate firefighting). The fire in Rome was supposed to provoke mass riots and chaos, and the conspirators planned to exploit the situation by having an army of disgruntled peasants, shepherds, and gladiators seize first Italy and then Rome. Meanwhile, in the capital, the conspirators' forces were to kill all their enemies, with some nobles tasked with killing their parents. The primary task, however, was to kill Cicero. One of the conspirators and the consul’s informant, Quintus Curius, warned Cicero through his lover Fulvia. Cicero took countermeasures and avoided the assassination attempt.

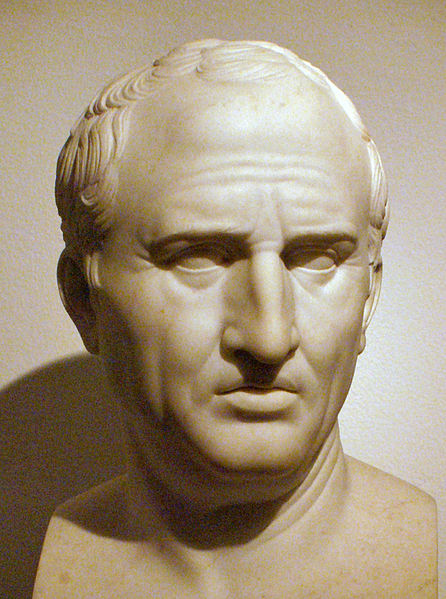

Marcus Tullius Cicero made every effort to aggrandize himself after uncovering the conspiracy.

Marcus Tullius Cicero made every effort to aggrandize himself after uncovering the conspiracy.

On November 7 or 8, Cicero convened a Senate meeting in the Temple of Jupiter Stator. The choice of location was symbolic, as the temple had been built in honor of the semi-legendary event when Romulus stopped the retreating Roman army. By choosing this site, the consul hinted that the time had come to stop Catiline. Additionally, the temple was easy to defend in case of unrest, and if necessary, it was close enough to the consul’s house to allow for a quick escape. Cicero’s speech, given before he had any concrete evidence of the conspiracy, is known as the First Catilinarian Oration. The leader of the conspiracy was present at the session but did not address the consul’s accusations directly, instead limiting himself to invective about Cicero’s lowly origins. Since Catiline received almost no support, he soon left the capital. Although Catiline claimed he was leaving for Massilia, in reality, he joined Manlius in Faesulae. In Roman tradition, voluntary exile was equivalent to an admission of guilt. It is noted that Catiline had other reasons to flee the city besides political ones: on the 13th, the Ides of November, the deadline for paying off debts was approaching, which threatened him with bankruptcy. On November 8 or 9, Cicero delivered his Second Catilinarian Oration. This time, he spoke at the Forum, addressing the people. The consul’s need to address the city’s residents might have been driven by rumors that Cicero had illegally forced Catiline, a favorite of many common Romans, to leave the city.

According to Sallust, the Senate offered a substantial reward to anyone who reported on the conspiracy: 100,000 sesterces and freedom for a slave, and 200,000 sesterces and immunity for a free man. Additionally, after learning of the conspirators’ plans to set the city on fire, Rome began to be patrolled at night by a guard under the command of plebeian aediles and night tresviri. Praetor Quintus Pompeius Rufus was sent with a detachment to suppress a gladiator uprising in Capua (their connection to Catiline is unclear), and Praetor Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer was sent to Picenum and Cisalpine Gaul. The proconsuls who had returned from the provinces with armies and were awaiting permission for a triumph also received assignments. Quintus Marcius Rex was sent to Faesulae, and Quintus Caecilius Metellus Creticus was sent to Apulia, where a slave uprising had begun. Marcius Rex entered into negotiations with Manlius, but the rebels did not comply with the proconsul’s demands to lay down their arms and seek justice through regular channels.

When it became known that Catiline had joined Manlius, he was declared an enemy of the state. New troops were sent to Etruria, where Sergius and Manlius had established themselves, and they were led by Gaius Antonius Hybrida, who was suspected of sympathizing with the conspirators. By this time, Catiline had proclaimed himself consul (indicating that he did not recognize the results of the recent consul elections) but took no decisive action, waiting for the uprising to begin in the capital. He also sent letters to many prominent Romans—perhaps to sow discord between them and Cicero.

Although Catiline fled from Rome, his accomplices remained in the capital, tasked with organizing the uprising. However, Sergius left not the most capable and decisive conspirators in charge of the secret organization in the city, but rather the most prominent ones—Lentulus Sura, a former consul known for his indecision, and former praetors Publius Autronius Paetus and Lucius Cassius. The more energetic Gaius Cornelius Cethegus, Lucius Statilius, and Publius Gabinius Capito, who called for immediate action, were forced to submit to Lentulus due to the traditional hierarchy. The signal to begin the uprising was supposed to be the convening of a public assembly by one of the tribunes, Lucius Bestia. The conspirators intended to assassinate Cicero, set the city ablaze in twelve locations (according to Plutarch's less credible version, they hoped to start even a hundred fires simultaneously), and amidst the ensuing chaos, open the gates to Catiline's army. Nevertheless, Lentulus preferred to wait for the Saturnalia (December 17), despite Cethegus insisting on immediate action.

It was during November that the trial of Lucius Licinius Murena began. He had been elected consul for the following year but was accused by another candidate, the jurist Servius Sulpicius Rufus, of violating election campaigning rules. The conspirators had an opportunity to exploit the divisions that surfaced during the trial: Cicero, for tactical reasons, defended Murena, who had violated a law that Cicero himself had passed against Catiline (lex Tullia de ambitu), while some nobles demanded Murena’s conviction regardless of the difficult internal political situation. However, the conspirators did not seize this opportunity—perhaps Lentulus delayed the uprising because of Catiline’s problems recruiting supporters in Etruria.

The final plans of the conspirators were revealed by the arrival of envoys from the Gallic tribe of the Allobroges in Rome. This tribe was dissatisfied with the tax collectors and the arbitrary rule of Roman governors, but their complaints in the capital were ignored. Following this, Lentulus, through his agent Publius Umbrenus, informed them of the impending uprising and disclosed his plans in an attempt to win their cooperation. However, the Allobrogian envoys, who initially agreed to help the conspirators, changed their minds and reported their conversation to Quintus Fabius Sanga, the patron of their community in Rome. He immediately informed Cicero. It is likely that the Gauls’ change of heart was influenced by the prospect of receiving a promised monetary reward instead of the uncertain chance of achieving justice through a dangerous conspiracy. Cicero persuaded the envoys to pretend they were still willing to help the plot in order to gather as much incriminating evidence against the Catilinarian conspirators as possible. Shortly thereafter, following Cicero’s instructions, they managed to convince the conspirators remaining in Rome to write letters outlining their commitments and sealing them with their personal seals. The Allobrogian envoys promised to use these letters to persuade their tribesmen. Knowing the time of the envoys’ departure from Rome, the praetors Lucius Valerius Flaccus and Gaius Pomptinus, at Cicero’s request, organized an ambush at the Mulvian Bridge on the night of December 3. At that time, along with the Allobroges, they also captured Titus Volturcius, who was escorting them to Catiline (the route to Transalpine Gaul passed through Etruria); a letter from Lentulus to Sergius was found on him. After seizing the letters from the envoys, Cicero was able to present the Senate with evidence of the conspirators' intentions (as an exception, the case was considered directly in the Senate, not in court or a public assembly).

The meeting took place on December 3 in the Temple of Concord, where all the conspirators, except for Ceparius who had fled to Apulia, were brought. Since Lentulus was an acting magistrate, Cicero, as his superior, personally brought him to the session. The conspirators acknowledged the authenticity of the seals on the letters, and until further investigation, the senators decided to place them under custodia libera (house arrest in the homes of prominent Romans); two were housed in the homes of Caesar and Crassus. A search of the conspirators’ homes revealed large arsenals of weapons.

On December 4, the Senate heard testimony from the conspirators’ courier, Lucius Tarquinius, who was captured while attempting to contact Catiline. In his account of the secret organization, he mentioned Marcus Licinius Crassus as one of the coordinators of the entire underground movement. This testimony against an influential Roman, who had directly contributed to uncovering the conspiracy, turned the senators against both the witness and even against Cicero, who was briefly suspected of wanting to slander Crassus. However, Cicero strove to remain impartial and even refused the influential senators' requests to implicate Caesar in the same case—Caesar was under suspicion, but no formal charges were brought against him.

"How long, O Catiline, will you abuse our patience? How long will this madness of yours mock us? To what extent will your unrestrained audacity vaunt itself? <…> Do you not realize that your intentions are exposed? Do you not see that your conspiracy is already known to all these present and has been uncovered? Which one of us, do you think, does not know what you did last night, what you did the night before, where you were, whom you summoned, and what decision you made? O times! O morals!"

— The opening of Cicero's First Oration against Catiline.

Cesare Maccari, "Cicero Denounces Catiline." 1888 CE.

Cesare Maccari, "Cicero Denounces Catiline." 1888 CE.

On December 5, 63 BCE, another Senate session took place, details of which are well documented in sources. Some prominent senators, including Crassus, chose to ignore the session. As the conspirators were deemed guilty, the question of punishing the arrested members of the secret alliance was brought to the forefront. Cicero, who presided over the session, invited all the senators to express their views. Traditionally, the first to speak was the consul for the coming year, Decimus Junius Silanus. According to Sallust, he proposed the death penalty, although in peacetime Roman citizens could not be sentenced to death in a regular court, with exile being the usual punishment for serious crimes. However, there is also speculation that Silanus ambiguously suggested the highest measure of punishment. Silanus' proposal was supported by the senators who spoke in turn until it was Caesar’s turn to speak. Caesar, elected as praetor for the following year and speaking after the elected and former consuls but before the many former praetors and junior magistrates, called for moderation and proposed that the conspirators be placed under lifelong imprisonment in different cities, far from one another (a proposal that was unusual, as the Romans did not practice imprisonment). Caesar's proposal was convincing, and some of those who had previously spoken, including Silanus, began to change their opinion. However, Cato the Younger then took the floor. He urged the senators to take decisive action during this difficult time and hinted at Caesar's involvement in the conspiracy. In his vigorous speech, Cato demanded the death penalty for the conspirators. After his speech, the senators overwhelmingly supported his proposal. Since the Senate session was held with open doors, the crowd outside attempted to attack Caesar due to the suspicions raised by Cato about his sympathy for the conspirators.

The legal basis for the death penalty was quite shaky: although Cicero had received extraordinary power under the senatus consultum ultimum, there was still the law of Gaius Gracchus (lex Sempronia de capite civium), which stipulated that the execution of a Roman citizen could only be sanctioned by a public assembly. Cicero, however, considered the crime against the state a sufficient reason to no longer regard Catiline and the other conspirators as Roman citizens. Caesar, however, disagreed with this interpretation, and his proposal in the Senate was aimed at preventing a possible violation of Gracchus' law. Cato, speaking last, suggested equating the conspirators who had confessed to planning the uprising with the actual perpetrators and appealed to the customs of the ancestors (mores maiorum), which demanded the death penalty for those convicted of crimes against the state. The decision made was also controversial for another reason: the right of the convicted to appeal to the public assembly (provocatio ad populum) was violated.

On the same day, the condemned were taken to the Mamertine Prison and strangled. A total of five Romans were executed on December 5—Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, Gaius Cornelius Cethegus, Publius Gabinius Capito, Marcus Ceparius, and Lucius Statilius. After the execution, Cicero addressed the gathered crowd with just one word: vixerunt ("they have lived"), after which, according to sources, the people greeted the consul with applause.

Mamertine Prison, where the five participants in the conspiracy were executed. Current condition.

Mamertine Prison, where the five participants in the conspiracy were executed. Current condition.

The Battle of Pistoria

After the execution of the conspirators, only one center of resistance remained on the Apennine Peninsula in Etruria, led by Manlius and Catiline. Additionally, for a time, there were detachments under Publius Sittius operating in North Africa.

Initially, many volunteers flocked to Manlius and Catiline, and the size of their army grew to between 7,000 and 20,000 soldiers according to different estimates. However, most of those who arrived at the camp were poorly armed. After receiving news from the capital about the uncovering of the conspiracy and the execution of the five leaders of the organization, the rebel army began to dwindle. Sergius led the troops north, but there the rebels found themselves trapped in a valley near Pistoria (modern-day Pistoia): Metellus' forces blocked the northern route, and Antony's forces blocked the road to the south. Wishing to avoid encirclement, Catiline decided to break through to the south. On the day of the battle (January 62 BCE), Antony handed over command of the troops to the experienced military officer Marcus Petreius, while Catiline personally led his followers into battle. As the battle took place in a narrow valley, both commanders positioned their most capable soldiers in the front ranks. The turning point of the fierce battle came when Petreius’ troops broke through the center and subsequently surrounded the flanks of the rebels. Although the rebels' situation became hopeless, the battle continued until the last rebel was killed: according to Sallust, very few surrendered. About 3,000 of Catiline’s followers died in the battle, including the leader of the conspiracy and Manlius.

"…many soldiers who left the camp to inspect the battlefield and loot found, upon turning over the bodies of the enemy, one — a friend, another — a host or relative; some even recognized their own adversaries, with whom they had fought. Thus, the entire army experienced mixed emotions: joy and sorrow, grief and gladness.

— Gaius Sallustius Crispus, The Conspiracy of Catiline, 61.8-9 (translated by V. O. Gorenshtein)"

The body of Catiline, who received numerous wounds, was found on the battlefield; according to Sallust, he was still alive when discovered by the Senate’s forces. Antony, still under suspicion for his possible involvement in the conspiracy, ordered Catiline’s head to be sent to the capital as proof.

Results

The conspiracy significantly influenced Roman political life. According to S. L. Utchenko, the supporters of Gnaeus Pompeius (Pompey) attempted to exploit the danger of the conspiracy, which Cicero had widely publicized, to lobby for military dictatorship for their patron. For example, the plebeian tribune Quintus Caecilius Metellus Nepos proposed calling Pompey back from the East with his army to defeat the forces of Catiline and Manlius, and also to allow Gnaeus to run for the consulship in absentia. The suppression of the conspiracy was followed by numerous trials against both alleged and real conspirators, some of whom were defended by Cicero. Soon after, measures were taken that are seen as concessions to those sympathetic to Catiline: for example, Cato’s law of 62 BCE reduced the price of state grain for citizens, and Clodius’ law of 58 BCE made grain distributions free. Additionally, the agrarian laws of the 50s BCE, particularly Caesar's legislation of 59 BCE, are considered a reaction to Catiline’s movement.

The suppression of the conspiracy played a decisive role in Cicero’s subsequent life. Marcus frequently reminded people of his role in uncovering and suppressing the conspiracy, but over time he lost a sense of moderation:

"…[Cicero] provoked general displeasure with his constant self-praise and self-aggrandizement. For neither the Senate nor the courts could convene without hearing his tirades about Catiline and Lentulus. He even began to fill his books and writings with praise for himself."

— Plutarch, Cicero, 24 (translated by V. V. Petukhova)

Although Cicero was soon granted the honorary title "Father of the Fatherland" (pater patriae or parens patriae) in the atmosphere of general jubilation following the elimination of Catiline’s threat, the consul's enemies did not forgive him for overstepping his authority in executing the five conspirators. As early as the end of 63 BCE, tribune Metellus Nepos forbade him from delivering the traditional account of his consulship. In 58 BCE, another tribune, Clodius, succeeded in passing a law that exiled from Rome all magistrates who executed Roman citizens without a trial. The law was retroactive, and Cicero was forced to leave the capital, although he was allowed to return the following year. Finally, Lentulus’ execution laid the groundwork for the hostility of the future triumvir Mark Antony, Lentulus’ adopted son, toward the organizer of the execution. Twenty years later, Antony insisted on including Cicero in the proscription lists. According to tradition, Cicero's head and hands were displayed on the Forum after his execution, where he had often addressed the Roman people.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero

Literature

- Cambridge Ancient History. — 2nd ed. — Volume IX: The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 BC. — Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992. — P. 340.

- Kovalev S. I. Istoriya Rima [History of Rome], Leningrad: LSU Publ., 1948.

- Utchenko S. L. Drevnyj Rim [Ancient Rome]. Events. People. Ideas, Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1969.

- Gruen E. S. Notes on the «First Catilinarian Conspiracy» // Classical Philology. — 1969. — Vol. 64, No. 1.

- (Suet. Iul. 9) Suetonius. Divine Julius, 9.

- Utchenko S. L. Tsitseron i ego vremya [Cicero and His Time], Moscow: Mysl', 1972.

- Scullard H. H. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68. — 5th edition. — London; New York: Routledge, 2011. — P. 91.

- Jones F. L. The First Conspiracy of Catiline // The Classical Journal. — 1939. — Vol. 34, № 7. — P. 411—412.

- (Sall. Cat. 18) Sallust. On the conspiracy of Catilina, 18.

- Gasparov M. L. Suetonius and his Book / / Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. The Life of the Twelve Caesars, Moscow: Pravda, 1988, p. 360.

- Broughton T. R. S. The Magistrates of the Roman Republic. — Vol. II. — N. Y.: American Philological Association, 1952. — P. 159.

- Jones F. L. The First Conspiracy of Catiline // The Classical Journal. — 1939. — Vol. 34, № 7. — P. 411.

- Utchenko S. L. Yuli Tsezar-M.: "Mysl", 1976. - pp. 61-62.

- Jones F. L. The First Conspiracy of Catiline // The Classical Journal. — 1939. — Vol. 34, № 7. — P. 410.