Gaius Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) was an ancient Roman politician, statesman, military leader, and writer of Ancient Rome.

Based on the majority of ancient authors such as Suetonius, Appian, Plutarch, and Velleius Paterculus, it is widely accepted that Caesar was born in 100 BCE. However, the German historian Theodor Mommsen believes that he was born in 102 BCE because Caesar held all his magistracies two years earlier than usual. French historian Jérôme Carcopino suggests the year 101 BCE. The exact date of his birth is also a subject of debate, with some arguing for July 12 or 13.

According to legend, the noble Julian family traced their ancestry back to the goddess Venus and the Trojan prince Aeneas, who escaped the fall of Troy and settled in Italy at the site of present-day Rome. Among Caesar's ancestors were a dictator, a master of the horse (a high-ranking military office), and a member of the decemviri who participated in drafting the "Twelve Tables" of Roman law. The true origin of the cognomen "Caesar" is unknown, as it was already forgotten during the Roman era. However, there is a hypothesis that the cognomen derived from the Etruscan language, where it meant "god." Similar origins can be found in Roman names like Caesius, Cesonius, and Cezennius.

In the early 1st century BCE, there were two branches of the Julius Caesar family in Rome, but over time they diverged in their political views. Some supported Sulla, while others, including Caesar's closest relatives, were supporters of Gaius Marius, as Julia, the sister of Gaius Julius Caesar, became the wife of Gaius Marius.

On his mother's side, Caesar's relatives belonged to the Roman nobility. His mother, Aurelia Cotta, came from the distinguished and well-off Aurelian family. His paternal grandmother descended from the ancient Roman Marcii family. Ancus Marcius was the fourth king of Ancient Rome, reigning from 640 to 616 BCE.

Caesar was raised in the impoverished ancient Roman district of Subura. His parents made sure he received a decent education: he studied Greek, poetry, and oratory, learned to swim and ride horses, and engaged in physical exercises. Interestingly, young Caesar was taught rhetoric by the same teacher who taught Cicero. In 85 BCE, Caesar's father passed away, and after the initiation ceremony into adulthood, he had to assume leadership of the entire Julian family since there were no older males left in the lineage.

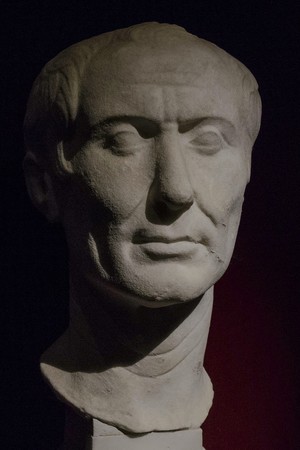

Portrait of Julius Caesar. Fine-grained marble. Rome, Roman National Museum, Palazzo Altemps

Portrait of Julius Caesar. Fine-grained marble. Rome, Roman National Museum, Palazzo Altemps

Political career

In the 80s BCE, Caesar, with the help of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, whose daughter Cornelia he was married to and had a daughter named Julia, became a Flamen (priest) of Jupiter. It was through this marriage, which followed the ancient confarreatio ritual (a solemn ceremony mainly performed in patrician families), that Caesar became a flamen. The performance of the ritual was a mandatory condition for a candidate for this position.

Shortly after the civil war between the Sullans and the Marianists, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, the victorious leader, came to power, and in 82 BCE, proscriptions (executions) began in Rome. Caesar, as a relative of Gaius Marius and the son-in-law of Cinna, was included in the infamous lists, but later he was removed from them with the help of other relatives. There is a legend that when Sulla saw Caesar and spared him, he uttered the following words: "You do not know what future awaits him and who he will become, but I see it, and that is why I spare him."

After that, Caesar, as one of the curule aediles - the children of senators and young knights who were trained in military affairs and provincial administration under the supervision of a magistrate - went to the province of Asia, where Mark Minucius Thermus was the governor. There, Caesar gained military experience during the siege of the city of Mytilene on the island of Lesbos, which resisted Roman authority. He also managed, on Thermus's orders, to persuade King Nicomedes IV of Bithynia to provide part of his fleet to assist the Romans in the war against Mytilene. Due to the success of this mission, rumors spread, instigated by Caesar's enemies, about his sexual relationships with King Nicomedes (see Etienne R. Caesar. Molodaya Gvardiya. 2003, pp. 86-93. Suetonius. The Divine Julius, 49).

After Asia, Caesar briefly fought against pirates in Cilicia, and upon learning of Sulla's death in 78 BCE, he hastily returned to Rome. Here, in 77-76 BCE, he engaged in legal activities, acting as a prosecutor in trials against former Sullans, but he did not achieve much success and temporarily departed to Rhodes to improve his oratory skills under the guidance of the renowned rhetorician Apollonius Molon. Molon was also the mentor of another famous Roman politician and orator of the late 1st century BCE, Marcus Tullius Cicero.

While Caesar was traveling to Rhodes, he was captured by Cilician pirates. Suetonius writes about this: "The pirates, with whom he was held captive, he swore that they would be crucified, but when he captured them, he ordered them to be beheaded first and then crucified" (Suetonius. The Divine Julius, 74). After being freed from pirate captivity and executing the pirates, Caesar returned to Rome around 74 BCE.

In 73 BCE, Caesar, instead of his deceased uncle Gaius Aurelius Cotta, was included in the college of pontiffs. The exact date of this event is uncertain: it could have occurred in 73, 72, or 71 BCE. Caesar was elected as a military tribune (see Gelzer M. Caesar: Politician and Statesman. - Harvard University Press, 1968. - p. 335 and Ross Taylor L. Caesar's Early Career //Classical Philology. 1941, Vol. 36, No. 2, p. 120). Sources provide little information about his military tribuneship, but there is a version that he may have participated in suppressing the Spartacus rebellion, during which he met Marcus Licinius Crassus, with whom he later formed the First Triumvirate (see Ross Taylor L. Caesar's Early Career //Classical Philology. 1941, Vol. 36, No. 2, p. 121).

At the beginning of 69 BCE, two tragedies occurred in Caesar's life. His wife and child died during childbirth, and his aunt Julia, the wife of Gaius Marius, also passed away. In the same year, Caesar became a quaestor, a Roman official responsible for finances, which guaranteed his entry into the Senate. He fulfilled his quaestorship in the province of Farther Spain. During this time, he met Lucius Cornelius Balbus, who would later become his trusted associate and friend. Upon his return from the province in 67 BCE, Caesar married Pompeia, the granddaughter of Sulla. At the same time, he started supporting the interests of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, first advocating for Pompey to be appointed as the leader of the campaign against pirates, and later as the new commander-in-chief in the Third Mithridatic War.

Advancing in his career, in 66 BCE, Gaius became the superintendent of the Appian Way, which he repaired at his own expense (according to Adrian Goldsworthy, with financial assistance from Marcus Crassus). Then, in 65 BCE, he became a curule aedile, responsible for organizing urban construction, transportation, trade, daily life in Rome, and festive events (usually at the aedile's own expense). Meanwhile, Caesar sought to restore the memory of Gaius Marius, which had been banned during Sulla's rule.

While serving as an aedile, Gaius held games in honor of the goddess Cybele (Megalesian Games) in April 65 BCE and the Roman Games in September of the same year, which amazed his contemporaries with their grandeur.

In 64 BCE, Gaius Julius Caesar assumed the position of judge in the permanent criminal court for cases of robbery accompanied by murder. As the head of the court, despite Sulla's law prohibiting the prosecution of his supporters, Caesar convicted many of Sulla's followers who had enriched themselves through proscriptions.

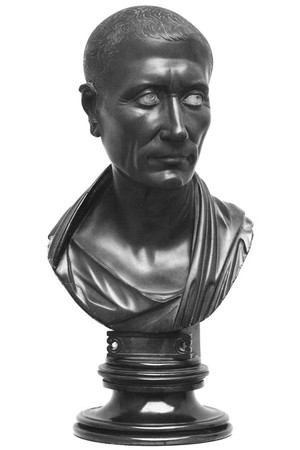

Portrait of Julius Caesar. Green slate. 10s BC-30s AD Height 41 cm Berlin, State museums, Antique collection

Portrait of Julius Caesar. Green slate. 10s BC-30s AD Height 41 cm Berlin, State museums, Antique collectionIn 63 BCE, when a vacancy opened up due to the death of the previous Pontifex Maximus, Caesar managed to secure the position through bribery. As Pontifex Maximus, he shed the restrictions imposed on him by the office of Flamen Dialis, which prohibited him from engaging in military and civil activities. In addition, his election to this position drew political attention to him and allowed him to move from Subura to the heart of Rome on the sacred road and reside in the official residence of the Pontifex Maximus.

It is not definitively proven whether Gaius Julius Caesar took part in the Catiline conspiracy in 63 BCE. Debates about this have persisted since ancient times. However, it is certain that he attended a Senate session in December 63 BCE, where the fate of the conspirators was being decided, and he even delivered a speech suggesting that the leaders of the uprising be sentenced to lifelong imprisonment with confiscation of their property instead of the death penalty. Caesar's speech aroused suspicion of his involvement in the conspiracy, as well as the anger of the Senate and the people. Marcus Porcius Cato the Younger and Cicero convinced the Senate not to accept Caesar's proposal and insisted on the execution of the conspirators, which ultimately took place.

In January 62 BCE, Caesar became a praetor. In ancient Rome, praetors were responsible for administering civil justice, and when consuls were absent from Rome, all supreme authority fell into the hands of the praetors. In this position, Gaius once again advanced the interests of Pompey, for example, proposing to assign him the reconstruction of the plan for Jupiter Capitolinus. However, Pompey's interests were countered by the Senate, and Caesar's proposals were not taken into account.

Caesar's reputation was damaged by an incident involving his wife Pompeia in December 62 BCE. She was hosting a festival in honor of the Good Goddess, which was attended by women. Publius Clodius (who would later become a notorious radical plebeian tribune) infiltrated the house disguised as a woman to meet with Pompeia. Caesar divorced his wife without waiting for a trial, as she had also failed to give him children. This episode from Caesar's life is associated with one of his famous phrases: "Caesar's wife must be above suspicion." Different variations of this phrase are mentioned in various sources.

Before his term was up (supposed to end in early 61 BCE), due to mounting creditors demanding repayment of numerous debts, Caesar, with the sponsorship of Crassus, departed as a propraetor to the province of Farther Spain.

Then, he first punished the dissatisfied inhabitants of the northern part of the province by sending troops there, and then he dealt with the daily affairs of governing the province. With the help of expensive gifts from wealthy residents of southern Spain, Caesar settled with most of his creditors and obtained a deferment from the remaining ones. Afterward, he voluntarily resigned from his position as propraetor in 60 BCE and returned to Rome. While traveling to or from Spain (this is not definitively known), passing through a small village, Caesar supposedly uttered the following phrase: "I would rather be the first man here than the second in Rome" (Plutarch, Caesar, 11).

Caesar presented the military suppression of the dissatisfied inhabitants of the northern province as a successful major military operation against "bandits," and the Senate was ready to grant him a triumph in Spain for this. However, such an honor jeopardized his ability to run for consul because a candidate granted a triumph was prohibited from crossing the city boundaries, and to participate in the elections, one had to submit their candidacy in Rome. Additionally, Caesar had gone through all the stages of the Cursus Honorum, the ladder of magistracies, reaching the minimum age for election to the consulship. Thus, Caesar found himself faced with a choice: either a triumph or the consulship. He requested the opportunity to be a candidate for consul through absentee nomination, as Pompey had been in 71 BCE, but his enemies did not grant him such a chance. In the end, Caesar chose the possibility of the consulship, sacrificing his triumph and entering the city as a private individual.

Around the same time, shortly before or immediately after the elections in 60 BCE, at Caesar's initiative, a triumvirate was formed, later known as the First Triumvirate. Besides Caesar, it included Marcus Licinius Crassus and Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, allowing politicians and military commanders to unite. Crassus was a comrade and financier who had been assisting Caesar, while Pompey was a successful general whom Caesar had started supporting some time ago.

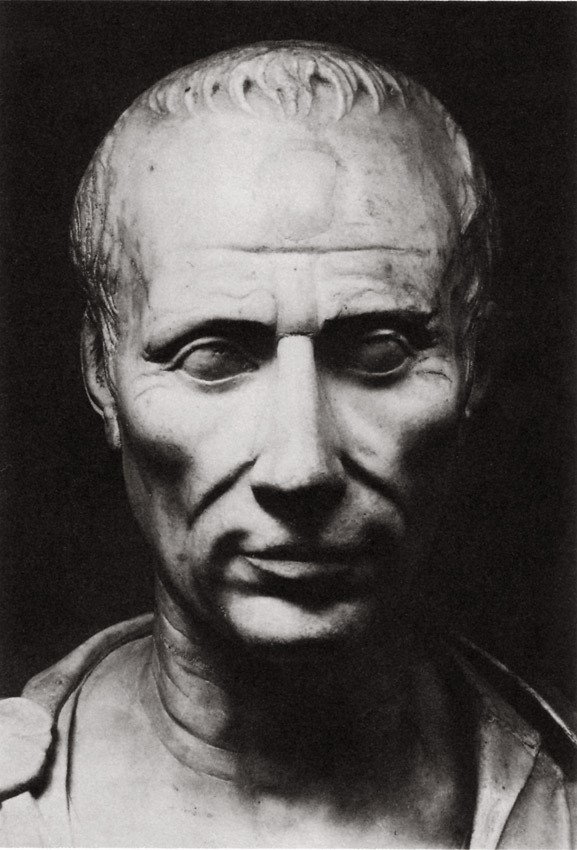

Gaius Julius Caesar. Modern work of the 17th or 18th century Rome, Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum, New Wing, 30i. Rome, Vatican Museums, Pius Clement Museum, Bust Gallery.

Gaius Julius Caesar. Modern work of the 17th or 18th century Rome, Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum, New Wing, 30i. Rome, Vatican Museums, Pius Clement Museum, Bust Gallery.

The Gallic War and the First Triumvirate

The First Triumvirate emerged in 60 BCE when Pompey, Crassus, and Caesar were not individually strong enough to seize power in the state. In 59 BCE, with the support of Pompey and Crassus, Caesar was elected consul. His co-consul was Marcus Bibulus, with whom Caesar constantly argued and fought throughout their consulship. Eventually, Bibulus was forced to resign from his consulship in protest against his colleague's actions. A joke circulated among the people that it was now the year of the consuls Caesar and Bibulus. (Suetonius. Caesar. 20)

After completing his consulship and obtaining the rank of proconsul in 58 BCE, Caesar departed for Gaul to wage the Gallic War. Around the same time, he organized the marriage of Pompey to his daughter Julia. In May 59 BCE, Caesar himself remarried, this time to Calpurnia, the daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus from a wealthy and influential plebeian family.

By the time Caesar arrived in Geneva (modern-day Geneva) at the end of March 58 BCE, the Romans had already conquered the southern part of Gaul, where they established the province of Narbonese Gaul. Caesar was given control over this province, as well as Cisalpine Gaul and Illyricum, which were exceptions granted for a period of five years instead of the usual one.

Here is how Caesar described Gaul and the Gauls before the war with them: "Gaul as a whole is divided into three parts. One of these is inhabited by the Belgae, another by the Aquitani, and the third by those Gauls who in their own language are called Celts, in ours Gauls. All these differ from each other in language, institutions, and laws. The Garonne River separates the Gauls from the Aquitani, while the Marne and the Seine separate them from the Belgae." (Caesar. Commentarii de Bello Gallico, I, 1; translated by M. M. Pokrovsky)

At the beginning of the Gallic War (58-50 BCE), Caesar had 20,000 men under his command (four legions and auxiliary forces). During the war, the number of legions increased to ten. Caesar extensively described his successes in the "Commentarii de Bello Gallico" (Commentaries on the Gallic War). They have been published in Russian under the editorship of academician M.M. Pokrovsky. Some ancient and contemporary authors consider Caesar's plans for the Gallic War as a rehearsal for the civil war and the seizure of power in Rome, while others say that when starting this war, he dreamt of victories and laurels similar to those of Alexander the Great.

In addition to Caesar, the Gallic War is also described by Dio Cassius. Other ancient authors such as Plutarch, Appian, Florus, and Eutropius mention this war, but their accounts are brief and often imprecise, although they used many sources besides Caesar's notes.

The reason for the invasion of Gaul was a request sent to Caesar by several Gallic tribes who feared for their safety due to the increasing power of the Germanic leader Ariovistus, who lived in Gaul on part of the lands of the Aedui. During the Gallic War, Gaius Julius Caesar was able to gradually conquer all of Gaul through several military campaigns, suppress a number of uprisings by individual Gallic tribes, and the pan-Gallic uprising of 52 BC, led by Vercingetorix. During this time, he also invaded Germany and Britain twice to punish their peoples for aiding the Gauls and to demonstrate the strength and might of Rome. Throughout the Gallic War, the enemy forces outnumbered Caesar's forces many times over, but that did not prevent him from always emerging victorious from these battles, showcasing his brilliance as a commander, strategist, and tactician. This was especially evident in September 52 BC during the siege of Alesia (today the ruins near the modern city of Dijon, France), when Caesar defeated the Gallic forces both inside and outside the besieged stronghold. The Germans participated in this war under the leadership of Ariovistus, who was invited by some Gallic tribes (the Arverni and Sequani) to fight against the Aedui, whom he had defeated in 61 BC and remained on their territory with his warriors. Caesar defeated Ariovistus in the Battle of Vesontio (modern-day Besançon in eastern France) in 58 BC, and he soon died from his wounds.

During this war, Caesar was able to bring under Roman rule the Helvetii, Belgae, Usipetes, Tencteri, Treveri, Curiosolites, Venelli, Morini, Menapii, Venelli, Lexovii, Carnutes, Senones, and other tribes.

The legates in the Gallic War included Titus Labienus (who would later oppose Caesar in the civil war), Marcus Antonius (a close associate of Caesar who would later be a member of the Second Triumvirate and perish in the power struggle with Octavian Augustus), Publius Licinius Crassus (son of Marcus Crassus, who later called his son back for his Parthian campaign where both would perish), Quintus Tullius Cicero (younger brother of Marcus Tullius Cicero, who supported Pompey in the civil war, was pardoned and returned to Rome, later supported the assassins of Caesar and was executed by Mark Antony and Octavian), and others. During his stay in Gaul, Caesar maintained communication with Rome and was aware of everything happening there through his trusted representatives in the capital. He often intervened in the events and affairs taking place in Rome.

In 53 BC, Marcus Crassus died in Syria, and the triumvirate dissolved. Pompey and Caesar gradually began preparing for war against each other for power. The family ties between Caesar and Pompey were also severed when Julia, Pompey's wife and Caesar's daughter, died during childbirth in 54 BC.

While Caesar was suppressing the pan-Gallic uprising led by Vercingetorix in 53-52 BC, riots broke out in Rome due to the death of the famous politician Clodius. Pompey was temporarily appointed consul with unlimited powers to restore order in the capital. Soon, he passed laws on violent acts and bribery in elections. In parallel, Pompey and the plebeian tribunes enacted a decree that allowed Caesar to submit his candidacy for consul in absentia in 49 BC, something he failed to do in 60 BC. Shortly afterward, Pompey enacted a law on magistrates that.

Due to Pompey's uncertain stance, Caesar's situation regarding his candidacy for the consulship became more complicated, as his opponents wanted to reject Pompey's amendment and demand Caesar's presence in Rome as a private citizen for the elections. Caesar was seriously concerned that once he arrived in Rome and relinquished his authority, which granted him immunity, his enemies would bring him to trial as a private individual. Additionally, due to contradictions in the laws, it was unclear by what deadline the new governor, who was an opponent of Caesar, should arrive in Gaul. Backstage wars began over the new legislation.

By 50 BC, the rift between Pompey and Caesar became evident. At that time, Caesar had a significant military force as well as the support of the Roman plebs (common people) and a faction of the nobility (the ruling class of Ancient Rome, consisting of patricians and wealthy plebeians) whom he had bought with hefty bribes. Realizing that war with Pompey and, therefore, the majority of the Senate was imminent, Caesar decided to negotiate with them, offering mutual concessions. Although Caesar's opponents became consuls in 49 BC, he managed to place his supporters in the tribunes of the plebs. One of Caesar's tribunes in 49 BC was Mark Antony.

In January 49 BC, the Senate passed an extraordinary law calling citizens to arms, indicating a refusal to engage in any further negotiations. Antony and his colleagues were given a hint that they were no longer safe, prompting them to flee from Rome. Afterward, the Senate issued an ultimatum to Caesar: if he did not resign from his propraetorship, he would be declared an enemy of the state. New governors for Narbonese Gaul and Cisalpine Gaul were also appointed.

The Civil War of 49-45 BC:

Caesar began assembling troops on the border with Italy as early as 50 BC. However, by January 49 BC, he only had the soldiers of the 13th Legion and about 300 cavalrymen at his disposal. Nevertheless, he decided to take action. With his army, Caesar crossed the border river Rubicon around January 10, thus initiating the civil war. According to Roman laws, a commander who reached this river, which marked the boundaries of Italy, had to disband his troops and enter Italy as a private citizen; otherwise, it would be considered a rebellion.

According to legend, while crossing the Rubicon, Caesar uttered one of his famous phrases, "Alea iacta est" (The die is cast), signifying that the decision had been made and there was no turning back.

In this war, the forces of Caesar clashed with those of Pompey and the Senate. Pompey, caught off guard by Caesar's swift advance, began retreating from Italy to Greece, counting on the support of the eastern provinces where his influence had been significant since the Third Mithridatic War.

Through a policy of pardoning less active enemies and incentivizing those who remained neutral or hesitated in choosing sides, Caesar rapidly advanced and encountered little resistance from the outset of the war. As Suetonius writes, "While Pompey declared as enemies all who did not stand up in defense of the republic, Caesar proclaimed that he would consider as friends those who abstained and did not join anyone" (Suetonius, The Divine Julius, 75).

Caesar couldn't immediately head to Greece, so Pompey gathered the entire fleet under his command. Additionally, Pompey's legates had been in Spain, behind Caesar's lines, since 54 BC, and that was where Caesar directed his forces to secure himself. Caesar appointed Mark Antony as the governor of Italy, granting him the powers of a propraetor. However, he entrusted the governance of Rome itself to the praetor Mark Lepidus (a future participant in the second triumvirate) and the remaining senators. By the end of August 49 BC, Caesar neutralized Pompey's forces in Spain.

While Caesar was fighting the Pompeians in Spain, in Rome, Mark Lepidus managed to have Caesar appointed as dictator, which Caesar learned about while en route from Spain to Italy, near the walls of the city of Massilia (modern-day Marseille, France), which his troops were besieging. Upon arriving in Rome and utilizing the powers of a dictator, Caesar organized elections for magistrates for the following year.

Caesar himself and Publius Vatinius Isauricus became consuls, and most of the other positions were filled by Caesar's supporters. While Caesar was at war in Spain and issuing laws in Rome, his commanders suffered a series of defeats against Pompey's generals in Africa and the Adriatic coast, forcing Caesar to cross to Greece solely by sea. In January 48 BC, he transported part of his forces to Greece. Caesar took a significant risk as it was storm season at sea, there was a shortage of supplies and ships, and Pompey's fleet controlled the waters. However, he personally crossed with a portion of his troops in January, while the remaining forces, under the command of Mark Antony, could only join him in April 48 BC

The first major battle between Pompey and Caesar took place near the city of Dyrrhachium in July 48 BC. Caesar lost and retreated. For unknown reasons, Pompey did not pursue Caesar. According to the ancient historians Plutarch and Appian, Caesar reportedly said the following words after this battle: "Today the victory would have gone to the enemy if they had someone to take advantage of it" (Plutarch, Caesar, 39. Appian, Civil Wars II, 62).

To replenish supplies and restore his forces, Caesar withdrew from Dyrrhachium to Thessaly. The decisive battle between Caesar and Pompey took place in August 48 BC. Caesar deciphered Pompey's plan to strike with cavalry against his infantry on the right flank and took countermeasures. As a result, the battle ended in a resounding victory for Caesar, and Pompey fled to Egypt via Cyprus, believing that Ptolemy XII, the indebted pharaoh, would support him in his struggle against Caesar. However, the advisors persuaded the pharaoh to refuse Pompey, lured him into a trap, and killed him. Pursuing Pompey, Caesar soon arrived in Egypt, where he was presented with Pompey's head and right hand, bearing his seal. Besides the pursuit, Caesar wanted to resolve his financial issues in Egypt by collecting a portion of an old debt from Ptolemy XIII (when his father, Ptolemy XII, sought to ascend the throne, he intended to offer a bribe to Consul Caesar for the recognition of the deceased Ptolemy XI's will, but he only managed to deliver part of the money). While in Egypt, Caesar became infatuated with Cleopatra. Initially, he intended to mediate in the dispute over who would rule Egypt - Ptolemy XIII or his half-sister Cleopatra - but he succumbed to Cleopatra's charms and took her side. This led to a military conflict between Caesar and Ptolemy XIII.

Soon, Caesar and Cleopatra were besieged in the royal palace in the city of Alexandria, but reinforcements arrived and helped tip the war in Caesar's favor. The forces of Ptolemy XIII were defeated, and Cleopatra became the ruler of Egypt.

In July 47 BC, Cleopatra gave birth to a son whom they named Caesarion. However, Caesar's paternity was doubted even in ancient times, so Caesarion was not officially declared Caesar's heir. Leaving three legions in Egypt to maintain order, Caesar returned to Rome. However, during this time, several eastern provinces decided to secede from Rome in the midst of a civil war, forcing Caesar to go there and then to Africa to defeat the Pompeian supporters who had established themselves there.

In the east, Caesar defeated the army of Pharnaces II, the son of Mithridates VI, in just three days and famously declared, "I came, I saw, I conquered" (Latin: Veni, vidi, vici).

By April 46 BC, Caesar managed to eliminate the Pompeian supporters in Africa (Battle of Thapsus), but some of them fled to Spain, where a new resistance stronghold against Caesar emerged. Despite this, Caesar returned to Rome, where he celebrated four consecutive triumphs: for his victories over the Gauls, Egyptians, Pharnaces, and Juba. Along with the triumph for the victory over Juba, the triumph also honored Caesar's victory over other Romans, the Pompeian supporters.

In November 46 BC, Caesar went to Spain to eliminate the last remaining stronghold of the civil war. In the Battle of Munda in March 45 BC, Caesar managed to defeat the Pompeians and returned to Rome. The only surviving son of Pompey the Great, Sextus, escaped alive from Spain and later settled on the island of Sicily, ultimately outliving Caesar.

In Rome, Caesar celebrated his fifth triumph, which became the first triumph in Roman history to honor the victory of Romans over Romans.

Denarius, silver. Date of minting: 49-48 BC Mint: Gaul (mint that moved with Caesar)

Denarius, silver. Date of minting: 49-48 BC Mint: Gaul (mint that moved with Caesar)

Dictatorship of Caesar and His Reforms

Until 45 BC, Caesar's term as dictator was extended three times, and in 45 BC, he was elected dictator for 10 years. By this time, Caesar held the positions of dictator, proconsul, consul, tribune of the plebs, and "prefect of morals" - censor, as well as the position of Pontifex Maximus.

In 44 BC, Caesar added the title "imperator" to his name, which at that time was given to a successful military commander in Rome, and he now bore the name Imperator Gaius Julius Caesar. And in February 44 BC, his dictatorship was legislatively established for life.

Many expected that within a year, Caesar would pass the desired laws and relinquish his powers, like Sulla, who also held the position of dictator indefinitely, implemented his reforms over several years, retired, and became a private citizen. But Caesar declared that he would rule in this position until the end of his days. In honor of the goddess Venus, he built a temple on the Forum, popularizing the legend of his descent from this goddess.

In early 44 BC, the Senate and the Assembly, with the assistance of Mark Antony, passed a series of laws completing the deification of Caesar and the establishment of his cult in Rome:

- Gaius Julius Caesar was given the title "Father of the Fatherland" (Latin: pater patriae).

- He also had the right to place his profile on coins, a privilege not granted to any living figure before him.

- A special oath in honor of Caesar's genius was introduced, which all magistrates had to take upon assuming office.

- The month of Quintilis was renamed July.

- Annual sacrifices were instituted to invoke the gods for Caesar's safety.

- One of the Roman tribes was renamed in honor of Gaius Julius Caesar.

- His birthday was to be celebrated with games and sacrifices.

- All temples in Rome and Italy were required to install statues of Caesar.

- Construction of the Temple of Concordia, in honor of the reconciliation of the state, was to begin in Rome.

In 44 BC, Caesar took several steps to align his image with that of former Roman kings. He would sit on a throne without rising when approached by senators, and he constantly wore a laurel wreath and the attire of a triumphator. On several occasions, he was openly offered the title of king, but Caesar refused it. It is likely that the idea of making such an offer originated from Caesar himself to gauge the reaction of Roman society.

During and after the civil war, using his power and bribery, Caesar implemented a series of reforms from 49 to 44 BC. It is difficult to determine with certainty which of his reforms were enacted, as our knowledge of them comes only from later authors writing during the Roman Empire, and the calendar reform in 45 BC further complicates matters. Contrary to tradition, Caesar himself issued many laws, although it was officially declared that they were enacted with the consent and approval of the Senate. Additionally, matters of foreign policy were now decided by Caesar alone, not the Senate.

Caesar's reforms as dictator included:

1) Prohibition of raising interest rates on loans beyond 6% per year.

2) Establishment of a central administrative apparatus.

3) Distribution of land plots to veterans, including in the provinces.

4) Changes in the composition of the Senate (expanding it to 900 members and introducing many of his own supporters).

5) Minting of coins with his own image.

6) Abolition of debts for rent.

7) Granting of privileges to residents of the provinces. Only cities in the western provinces received Roman citizenship, while cities in Greece and Asia Minor did not receive such privileges.

8) New Roman colonies were established in the provinces under the leadership of Caesar's veterans.

9) Reduced the amount of free bread distributed.

10) Reduced unemployment due to Caesar's extensive urban development policies.

11) In the provinces of Asia and Syria, taxes based on a redemption system were converted to direct taxes.

12) New laws were enacted against luxury, prohibiting pearl jewelry, personal sedans, and elaborate decorations on gravestones; the sale of extravagant products was regulated.

13) Exile was established as punishment for certain crimes, and wealthy Romans had half of their estates confiscated.

14) In 46 BC, a calendar reform was carried out, replacing the previous lunar calendar with a solar calendar developed by the Alexandrian scholar Sosigenes. It consisted of 365 days with an additional day every four years (leap year).

Gaius Julius Caesar. Consul 59, 48, 46-44; dictator 49-44 BC Proconsul Gaius Vibius Pansa. AE 24, copper. Date of minting: 47-46 BC Mint: Nike

Gaius Julius Caesar. Consul 59, 48, 46-44; dictator 49-44 BC Proconsul Gaius Vibius Pansa. AE 24, copper. Date of minting: 47-46 BC Mint: Nike

Conspiracy and Assassination of Caesar

Before the conspiracy in 44 BC, several attempts on Caesar's life had been made, but they were all uncovered long before they could be carried out. In early 44 BC, as Caesar prepared for his campaign against Parthia and rumors circulated in Rome about his impending coronation, a conspiracy against Caesar emerged among the Roman elite. The conspirators feared Caesar's growing influence and the rumors circulating in the capital that he would soon be declared king.

The leaders of the conspiracy were Marcus Junius Brutus (a relative of the same Marcus Brutus who overthrew the kings' rule in Rome and established the republic) and Gaius Cassius Longinus (one of the few who managed to return alive to Rome from Crassus' ill-fated campaign in Parthia). The conspiracy included both former Pompeians and many of Caesar's supporters. The number of conspirators increased after an attempt to place a royal diadem on Caesar during the Lupercalia festival, from which he initially refused.

The implementation of the conspiracy was set for March 15th - the Ides of March (the middle of the month), when the Senate was supposed to convene in Pompey's Curia. According to accounts from ancient authors, shortly before the Ides of March, Caesar's supporters made several attempts to warn him of the conspiracy, but due to circumstances, he either did not listen to them or did not believe their words.

According to the conspirators' plan, they had to distract Mark Antony, who could have come to Caesar's defense, from the Senate. One of the senator-conspirators achieved this by leading Antony out of the Curia for a short time under a pretext. Then Caesar would be surrounded by a group of opponents, with Lucius Tillius Cimber stepping forward to plead for the pardon of his brother. When Caesar began to read the document presented to him, the conspirators would attack him from all sides. Almost everything happened as planned, although Caesar managed to briefly read the document and Cimber had to give the signal to act by pulling Caesar's toga from his neck. Caesar was then assaulted from all sides with styluses and daggers that the adversaries had managed to conceal under the folds of their togas during the Senate session.

The first blow to Caesar's neck was struck by Publius Casca. Caesar resisted, but when he saw Marcus Brutus among the assassins, he stopped resisting and merely said, "And you, child."

Plutarch describes the final moments of Caesar's life as follows: "When Gaius saw Brutus, he fell silent and stopped resisting." The same author notes that Caesar's body accidentally ended up near the statue of Pompey that stood in the room, or it was intentionally moved there by the conspirators themselves. A total of 23 wounds were found on Caesar's body. After the funeral games and several speeches, the crowd burned Gaius' body in the forum, using benches and tables from market traders as a funeral pyre. (Plutarch. Caesar. 66.68).

Suetonius described Caesar's funeral as follows: "Some suggested burning him in the Temple of Jupiter Capitolinus, others in Pompey's Curia, when suddenly two unknown men appeared, armed with swords, waving torches made of wax, and set the structure on fire. Immediately, the surrounding crowd began to drag dry kindling, benches, and judges' chairs into the flames, along with everything that had been brought as offerings. Then flute players and actors tore off their triumphal garments worn for that day and, tearing them apart, threw them into the fire; old legionaries burned the weapons with which they had adorned themselves for the funeral, and many women burned their headpieces, bullae, and children's clothes." (Suetonius. The Divine Julius. 84).

According to the will, Caesar allocated 300 sesterces to each Roman citizen from his estate, and the gardens above the Tiber were transferred for public use. (Suetonius. The Divine Julius, 83).

Unexpectedly for everyone, especially for Mark Antony, Caesar's grandnephew Gaius Octavius was declared his heir, later known as Augustus, receiving three-quarters of Caesar's wealth.

Later, a second triumvirate will be formed between Octavius and Antony, including Marcus Lepidus. Eventually, Octavius, after defeating Mark Antony and removing Lepidus from power, will become the sole ruler of Rome and complete the process of transforming the Roman Republic into the Roman Empire, becoming its first emperor.

The Image of Caesar in Culture

Contemporaries had different assessments of Caesar: his political opponents mocked him and accused him of immorality, while his supporters praised him in every way.

By the 1st century BCE, through the efforts of Octavian, who emphasized his connection to Caesar, the main aspects of the myth of the divine Julius - the great politician and military leader - were largely established, and many shared the official point of view.

During the Middle Ages, until the 14th century when the Renaissance era began, Caesar was regarded as a just conqueror and an unquestionable military authority, but later he came to be seen as a tyrant. However, the contradictory assessment of Caesar did not affect the popularity of his writings.

In the 16th century, in addition to Caesar's fame as a military commander, he also gained recognition as a military theorist, thanks to the increasing role of infantry in European armies.

The personality of Gaius Julius Caesar has always attracted the attention of researchers of ancient history, and assessments of his rule have varied. Many books and scholarly monographs have been written about Caesar and his life, by authors such as Mommsen, Utchenko, and others.

Related topics

Roman Republic, First Triumvirate, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Plutarch. Comparative biographies. Caesar.

2. Suetonius. Divine Julius, 88.

3. Appian. Civil Wars, II, 149.

4. Vellei Paterkul. Roman history

5. A brief description of the wars from the books of the Caesarievs with some notable signs about those wars, with a special conversation about the war. Moscow, 1711. (translation of the book by Henri de Rohan - "pale reflection" of Caesar[522])

6. Caius Julius Caesar notes on his campaigns in Gaul. Translated by S. Voronov. St. Petersburg, 1774. 340 p.

7. Works of K. Yu. Caesar. Everything that has come down to us from him or under his name. With an appendix of his biography, written by Suetonius. / From Lat. translated and published by A. Klevanov, Moscow, 1857.

Tsch. 1. Notes on the Gallic War. LIV, 214 p.

Tsch. 2. Notes on the internal war and other campaigns of Caesar. 265 p. (pp. 240-265. The Spanish War).

8. Shramek I. F. Detailed dictionary to the Notes of K. Julius Caesar on the Gallic War. St. Petersburg, 1882. 276 stb.

9. Notes on the Gallic War. Translated by V. E. Rudakov. St. Petersburg, 1894. 196 p.

10. Notes on the internecine war. Translated by I. Kelberin. Kiev-Kharkiv, 1895. 384 p.

11. Notes on the Gallic War. / Lowercase and lit. translation, syntactic turns, words. / Comp. by A. Novikov. St. Petersburg, Classics for students. 1909. Issues 1-7.

12. Seven books of Notes on the Gallic War. / Translated by M. Greenfeld. Odessa, 1910?. 322 p.

13. Notes of Julius Caesar and his successors on the Gallic War, on the Civil War, on the Alexandrian War, on the African War / Translated by M. M. Pokrovsky. (Series "Literary monuments") M.-L., Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1948, 560 p. 5000 copies. (there are reprints).

14. Pseudo-Caesar. The Spanish War. Translated by Yu. B. Tsirkin. / Tsirkin Yu. B. Antichnye i rannesrednevekovye istochniki po istorii Espanyi [Ancient and early Medieval sources on the history of Spain]. SPb.: SPbSU Publishing House, 2006, 360 p.-pp. 15-31.

15. Divide and conquer!: Notes of the triumphator / Translated from Latin-Moscow: Eksmo, 2012. - 480 p.

Modern literature:

1. Utchenko S. L. Yuli Tsezar — Moscow: Mysl', 1976.

2. Grant M. Julius Caesar: Priest of Jupiter, Moscow: Tsentrpoligraf Publ., 2003.

3. Tom Stevenson. Julius Caesar and the Transformation of the Roman Republic . 2014.

4. Mommsen T. Istoriya Rima [History of Rome], Vol. 3, St. Petersburg: Nauka Publ., 2005.

5. Grabar-Passek M. E. Julius Caesar and his successors / History of Roman literature. Edited by S. I. Sobolevsky, M. E. Grabar-Passek, and F. A. Petrovsky, vol. 1, Moscow: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1959.

6. Goldsworthy A. Tsezar. - Moscow: Eksmo, 2007. - 672 p.

7. Etienne R. Caesar, Moscow: Molodaya gvardiya Publ., 2009, 304 p.

8. Kornilova E. N. "The Myth of Julius Caesar" and the idea of dictatorship: Historiosophy and fiction of the European Circle, Moscow: MGUL Publishing House, 1999.

9. Durov V. S. Julius Caesar. Man and Writer, Leningrad: LSU Publishing House, 1991, 208 p.

10. Billows R. Julius Caesar: The Colossus of Rome. — London; New York: Routledge, 2009. — 312 p.

11. Carcopino J. César. — Paris: PUF, 1936. — 590 p.

12. Gelzer M. Caesar: Der Politiker und Staatsmann. Aufl. 6. Wiesbaden, 1960; English translation-Gelzer M. Caesar: Politician and Statesman. — Harvard University Press, 1968. — 359 p.

13. Meier Ch. Caesar. - Munich: DTV Wissenschaft, 1993. - 663 S. English translation-Meier C. Caesar. — New York: Basic Books, 1995. — 544 p.