Second Triumvirate

A triumvirate (from the Latin triumviratus—"union of three men") was a political agreement, an alliance of influential political figures and military leaders in Rome during the civil wars of the 1st century BC, aimed at seizing power in the state.

In ancient Rome, the term referred to a collegium of three magistrates authorized by the Senate. During the height of the Early Republic, triumvirs were appointed from among the senators to administer newly conquered territories and establish Roman colonies. During the crisis of the Roman Republic, triumvirs were no longer senators and magistrates but three powerful politicians in Rome, often with one of them becoming weaker over time compared to the other two.

Members of the triumvirate were called triumvirs. In the second triumvirate, they referred to themselves by this title, while in the first triumvirate, the term was applied to them retrospectively after the establishment of the second triumvirate.

Members of the Second Triumvirate:

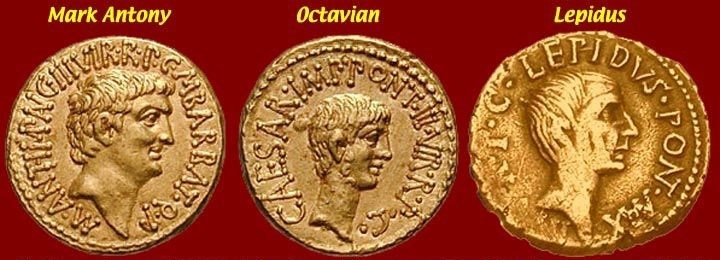

Gold coins with the profiles of the participants of the 2nd triumvirate

Gold coins with the profiles of the participants of the 2nd triumvirate

Creating the Second Triumvirate

Unlike the first triumvirate, whose exact formation date is unknown, there is much more information preserved about the second triumvirate. The second triumvirate was established in October 43 BC when Mark Antony (Caesar's ally and general), Octavian Augustus (Caesar's adopted son and heir), and Marcus Lepidus (an aristocrat and Caesar's general) met near Bononia (now the city of Bologna, Italy) and agreed to form the second triumvirate.

The primary goals of the second triumvirate were to seize power in Rome and avenge Caesar's assassins.

Additionally, the triumvirs divided key magistracies among their supporters for the coming years. They also partitioned the western provinces, while the eastern provinces were still under the control of Caesar's assassins:

- Mark Antony received all parts of Gaul except for Narbonese Gaul, which was given to Lepidus. In addition, in Africa, which was allotted to Octavian, a commander loyal to Mark Antony was in control of the army.

- Lepidus was given control over Spain and Narbonese Gaul.

- Octavian received Africa and nominal control over Sicily and Sardinia. The control was nominal because the actual ruler of these territories was Sextus Pompey, the son of the late Pompey.

Activities of the Second Triumvirate

The activities of the second triumvirate were legalized by the Lex Titia on November 27, 43 BC, three days after the triumvirs entered Rome. This law granted the triumvirs exceptional powers for five years, including the right to appoint high magistrates. To replenish their treasury and pay the salaries of the assembled troops, numbering up to 19 legions, the triumvirs compiled proscription lists and began a reign of terror against the aristocrats in Rome. As a result, many senators and equites, included in the lists, fled Rome to join Brutus and Cassius in the east or Sextus Pompey in Sicily. After replenishing the triumvirate's treasury, Antony and Octavian set off for Greece to confront the republican forces responsible for Caesar's assassination, leaving Lepidus in Italy. During this time, Lepidus handed over almost all his legions to Octavian, ceasing to be an equal partner in the triumvirate.

By this time, Brutus had taken control of all Roman territories in the Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor, while Cassius had occupied Syria. They managed to gather substantial funds and assemble a sizable army of 19 legions (about 100,000 soldiers) and a strong fleet.

Two decisive battles between the Caesarian and republican forces took place in October and November of 42 BC at Philippi (northern Macedonia, Greece). Approximately two hundred thousand men fought—19 legions on each side. The first battle ended in a draw: Antony defeated Cassius on the left flank, leading to Cassius's death, while Brutus was victorious against Octavian on the right flank. In the second battle, due to Octavian's illness, the troops were led by Antony, who defeated Brutus, who soon after died. The surviving republican soldiers were captured or surrendered, with some joining Antony's forces, while others fled to Sextus Pompey in Sicily.

After defeating Caesar's assassins and with the primary goal of the triumvirate achieved, the triumvirs—now only Octavian and Mark Antony, excluding Lepidus—once again divided the provinces and separated their spheres of influence, retaining their extraordinary powers.

Octavian received the western provinces and Rome, while Mark Antony was given the eastern provinces. As Octavian sailed to Rome with his forces, Mark Antony remained in the east with six legions and a large cavalry unit, preparing for a campaign against Parthia. Additionally, after the new division of lands, Lepidus lost Spain, which was given to Octavian, and Narbonese Gaul, which was transferred to Mark Antony. In Rome, Lepidus was stripped of his remaining three legions due to rumors of his ties with Sextus Pompey, who was based in Sicily. However, he was promised the administration of Africa if the rumors proved unfounded.

Later, despite Lepidus's unsuccessful involvement in the Perusine War on Octavian's side (the revolt of Mark Antony's brother, Lucius Antony, against Octavian's autocratic rule in Italy from autumn 41 to spring 40 BC, which was suppressed by Octavian), he was still given control over Africa and was sent there with six legions. For the next four years (40-36 BC), while Mark Antony and Octavian were engaged in wars (Octavian was fighting Sextus Pompey over Sicily, and Mark Antony was at war with Parthia and Armenia), they did not forget about Lepidus, with each trying to win him over to their side in the impending inevitable conflict between them.

Shortly before the end of the war with Sextus Pompey, Octavian and Mark Antony sought to hold another meeting to extend the triumvirate's term, as their powers were set to expire in December 38 BC. The meeting took place only in the spring of 37 BC in the city of Tarentum (now Taranto, Italy). Antony and Octavian agreed to extend the triumvirate's term for another five years. They also promised each other military support: Octavian offered Mark Antony four legions for his war against Parthia, while Antony intended to give Octavian 120 warships for his war against Sextus Pompey. Additionally, the consular lists were approved up to 31 BC. Lepidus's interests were not considered at this meeting.

Lepidus was finally excluded from the triumvirate in 36 BC after his defeat alongside Octavian in the war against Sextus Pompey, which Octavian won.

Antony handed over the ships promised at the Tarentum meeting to Octavian, who, under the pretext of the Illyrian War (a Roman province along the eastern Adriatic coast), did not send the legions to support Antony in his war against Parthia. In 36 BC, Lepidus, having sufficient forces, attempted to force Octavian to recognize his rights as a triumvir, but he failed, as his troops were swayed and bribed by Octavian. Lepidus was sent to Rome under arrest. Thus, the triumvirate was effectively reduced to a duumvirate, and preparations for the war between Mark Antony and Octavian for sole power over Rome began.

Antony and Octavian openly began to discredit each other in 33 BC, when Octavian became consul in Rome and started spreading rumors about Antony and Cleopatra. Antony responded in kind, accusing Octavian of deceit, particularly claiming that Octavian was not Caesar's biological son. In December 33 BC, the triumvirs' term expired, and Octavian relinquished his triumviral power, while Antony promised to do the same if constitutional order was restored in Rome as it had been before the civil wars. In reality, Antony did not relinquish his triumviral powers.

In 32 BC, Antony's supporters Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Gaius Sosius became consuls. They demanded the Senate approve all of Antony's decrees during this time. Sosius openly spoke out against Octavian, but the clash ended with the consuls and 300 senators fleeing to Alexandria to join Mark Antony after Octavian used military force. Octavian replaced the fleeing consuls with his friends, appointing them as consuls suffectus.

A consul suffectus was a temporary consul elected in place of a deceased or removed official consul. The consul suffectus had the same rights as an official consul for the duration of their term. Sometimes, there could be two consuls suffectus simultaneously, as during the civil wars in Rome, official consuls often died or fled from Rome. Opponents sought to eliminate the power of former consuls by electing consuls suffectus from their supporters.

The dissolution of the fragile peace and the conflict between Octavian and Mark Antony was triggered by Antony's divorce from Octavia, Octavian's sister, in the summer of 32 BCE. Antony formally acknowledged that Octavia had been living in Rome for some time, while he was cohabiting with Cleopatra, whom he officially married. This decision alienated some of Antony's supporters, who then defected to Octavian. Two of these defectors informed Octavian about the existence of a highly controversial will left by Antony.

Octavian immediately seized Antony's will from the Vestal Virgins and made it public, violating both legal and religious norms. According to Antony's will, his body was to be buried in Alexandria, Caesarion was to be recognized as Julius Caesar's legitimate heir instead of Octavian, and the majority of Antony's wealth was to be left to Cleopatra and their children, contrary to Roman law. There is a theory that this outrageous will was a forgery created by Octavian's supporters. Nonetheless, its publication was enough to garner the Roman people's support for Octavian.

Map of the territorial division of the Roman Republic among the members of the Second Triumvirate: Provinces that went to Octavian are marked in red; those given to Mark Antony are marked in yellow; the province that went to Lepidus is marked in gray. Other colors represent rulers who were either allies or enemies of the triumvirs.

Map of the territorial division of the Roman Republic among the members of the Second Triumvirate: Provinces that went to Octavian are marked in red; those given to Mark Antony are marked in yellow; the province that went to Lepidus is marked in gray. Other colors represent rulers who were either allies or enemies of the triumvirs.

The Dissolution of the Second Triumvirate

Formally, the triumvirate dissolved with the exclusion of Lepidus in 36 BCE, but it effectively came to an end after the civil war between Mark Antony and Octavian from 32-30 BCE, in which Octavian emerged victorious, and both Mark Antony and his ally, Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, died.

Octavian openly declared war on Egypt at the end of 32 BCE, and Antony's authority and his position as consul were annulled in 31 BCE. In 31 BCE, the last civil war in the history of the Roman Republic took place, leading to the transformation of the Republic into an empire. This war was fought between Octavian on one side and Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt, on the other, from 32-30 BCE.

The decisive battle of this civil war occurred on September 2, 31 BCE—the naval Battle of Actium. Antony and Cleopatra were defeated and fled to Egypt, where both died in 30 BCE. Egypt was then conquered and became a Roman province. Octavian became the sole ruler of the Roman Republic, which he transformed into the Roman Empire in 30 BCE, becoming its first emperor. The regime of Octavian Augustus' sole rule is known as the Principate.

Related topics

Roman Republic, First Triumvirate, Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, Principate, Cicero

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Plutarch. Comparative biographies. Mark Antony;

2. Appian. Civil wars;

3. Dion Cassius. Roman History; books 46-50.

4. Cicero. Philippics vs. Mark Antony.

Contemporary authors:

1. Eder, Walter. Augustus and the Power of Tradition (неопр.). — Cambridge, MA; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

2. Green, Peter. Alexander to Actium: The Historical Evolution of the Hellenistic Age (англ.). — Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles; London: University of California Press (англ.)русск., 1990. — (Hellenistic Culture and Society).

3. Rowell, Henry Thompson. (1962). The Centers of Civilization Series: Volume 5; Rome in the Augustan Age. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press

4. Scullard, H. H. From the Gracchi to Nero: A History of Rome from 133 B.C. to A.D. 68 (англ.). — 5th edition. - London; New York: Routledge, 1982 5. Syme, Ronald (engl.)Russian.. The Roman Revolution, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1939. The classic revisionist study of Augustus

6. Weigel, Richard D. (1992). Lepidus: the triumvir has been tainted . London, United Kingdom: Routledg