Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (c. 89-13/12 BC) came from a noble patrician family, the Aemilii, which ancient authors considered one of the oldest families in Rome. Many consuls and other state officials of Ancient Rome came from this family.

His father, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Senior, was a consul in 79-78 BC and a supporter of Sulla. After Sulla's death in 78 BC, Lepidus Senior attempted to revise his laws, which led to a conflict with the Senate. He then led a rebellion in Etruria, which was suppressed, and he was forced to flee to Sardinia, where he died in 77 BC.

In addition to Lepidus Junior, there were two other sons in his family: Lucius Aemilius Lepidus Paullus and Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus Aemilianus (adopted by Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus, the consul of 83 BC). We will provide more details about Lepidus Junior's older brother, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, later on. The middle brother, Lucius Aemilius Lepidus Paullus, managed to rise to the rank of consul in 50 BC. Initially, he had a negative attitude towards Caesar, but after receiving a large bribe from him, he maintained neutrality towards him. When Caesar was assassinated, Lepidus Paullus supported the assassins, for which he was even included in the proscription lists. However, with the help of his connections, including his older brother who was one of the three members of the Second Triumvirate, he managed to avoid death and save himself. He spent the rest of his life in one of the eastern provinces of the Roman Republic. The younger brother, Lucius Cornelius Scipio, who was adopted by Scipio Asiaticus, rose to the rank of legate. However, he perished when he supported the rebellion of his biological father, Lepidus Senior, in 77 BC, during its suppression.

Let's turn to the eldest of the three brothers, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Junior.

The first mention of Marcus Lepidus Junior in surviving sources dates back to 64 BC when he was among the members of the college of pontiffs (the highest priests in Ancient Rome). He is mentioned as a guest at a ceremonial dinner in honor of Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Niger's assumption of the position of priest of the god Mars. By the way, one of the guests at the same dinner was Gaius Julius Caesar.

In 61 BC, he held the position of a moneyer and was responsible for the production of coins.

In January 52 BC, he assumed the position of interrex to organize the consulship elections. Lepidus did not convene the comitia (assemblies) out of fear that supporters of the recently deceased Clodius would emerge victorious, which would have incurred the wrath of the crowd. As a result, his house was plundered.

Interrex was a position in Ancient Rome that existed since the time of the kings and throughout the Roman Republic. The interrex was responsible for convening the comitia (popular assemblies) for the election of the king during the early period and later the consuls under the republic. The term of office was 5 days, after which, if the duties were not fulfilled, another interrex was elected for the same term.

Afterward, Lepidus steadily ascended the Cursus honorum (the "course of honors"). He held the positions of quaestor and curule aedile. The date of Lepidus' quaestorship is unknown, but his aedileship is attributed to 53 BC.

Cursus honorum (Latin for "course of honor") was a list of successive military and civil-political positions (magistracies) held by Roman aristocrats of the senatorial class. This institution existed from around 180 BC (the Lex Villia) until the first century of the principate.

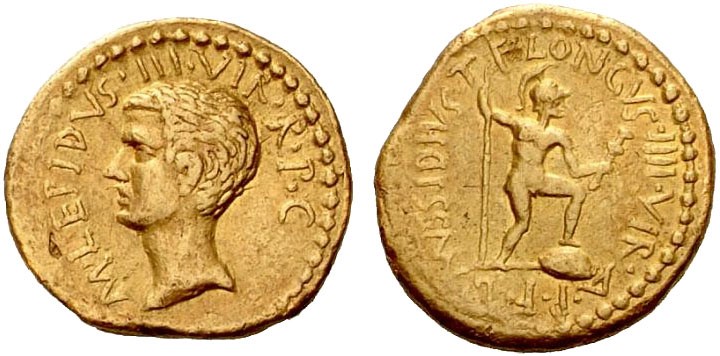

Golden Aurelius with a portrait of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus 42 BC Private collection

Golden Aurelius with a portrait of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus 42 BC Private collection

In 49 BC, Marcus Lepidus became a praetor and supported Gaius Julius Caesar, siding with him in the Civil War against Pompey. As a reward, Caesar granted him the title of proconsul of Hither Spain in 48 BC. There, he was able to quell the rebellion against the proconsul of Further Spain, Cassius Longinus (one of Caesar's associates), almost bloodlessly. For this, he was granted the title of imperator and awarded a triumph upon his return to Rome in the autumn of 47 BC.

In 46 BC, Lepidus, together with Caesar, became a consul. He then served as the commander of the cavalry and remained one of the highest magistrates in Rome for a time while Caesar was engaged in the African campaign.

Some historians believe that Caesar showered Lepidus with these honors because he viewed him as his successor instead of Mark Antony. However, Lepidus was later appointed governor of Narbonese Gaul and Hither Spain in 44 BC, which led to him losing the "title of second man in the state." Nevertheless, Lepidus sent trusted individuals to govern the provinces while he remained in Rome, retaining his position as the commander of the cavalry. After the assassination of Caesar on March 15, 44 BC, Lepidus was the first to restore order in the city by deploying troops and calling for revenge for Caesar's death. He joined forces with Mark Antony, who, like Lepidus, secretly aspired to take Caesar's place. However, in subsequent political intrigues, Lepidus lost and was sent to govern his provinces. But as a reward for restoring order in the capital after Caesar's assassination, he was granted a title that became vacant with the death of Gaius Julius Caesar, the Pontifex Maximus (Supreme Pontiff), the head of the college of pontiffs, the highest priestly position in Ancient Rome, which was a lifelong appointment.

In Spain, he encountered Sextus Pompey, the son of Pompey the Great, who began recruiting troops for his father. Through skillful negotiations, Lepidus convinced Sextus to leave the Iberian Peninsula and settle in Sicily. This occurred between March 44 and January 43 BC.

In 43 BC, Lepidus initially waited out the war that erupted between the senate and Octavian on one side and Mark Antony on the other. He then formed an alliance with Mark Antony.

Later, unexpectedly to the Senate, Octavian joined forces with Lepidus and Antony. Following their personal meeting in November 43 BC in Bononia (present-day Bologna, Italy), where Lepidus acted as an intermediary between Antony and Octavian, the Second Triumvirate was formed through a formal agreement. This agreement aimed to seize power over the Republic and punish Caesar's assassins. The western provinces were divided among the triumvirate, as the eastern provinces were still under the control of Caesar's assassins. Lepidus received Hither Spain, Narbonese Gaul, and Further Spain. The activities of the Second Triumvirate were legitimized by the Lex Titia on November 27, 43 BC, three days after the triumvirs entered Rome. According to this law, the triumvirs were granted exclusive powers, including the right to appoint the highest magistrates, for a period of five years.

Afterward, the terror in Rome began—the second proscription lists after Sulla's. One of the victims of this list was Marcus Tullius Cicero. By the way, Lepidus's middle brother, Lucius Lepidus Paulus, also ended up on these lists, but with the secret assistance of his elder brother Marcus Lepidus, he managed to escape and flee from Italy. After the executions and the replenishment of his and the other triumvirs' finances, Lepidus celebrated his Spanish triumph for his "victory" over Sextus Pompey in December 43 BC. In the new year of 42 BC, he became consul for the second time. This marked the peak of his power, as Antony and Octavian had departed to fight Caesar's assassins in the East, leaving Lepidus with a small portion of the army in Rome, making him the sole ruler.

However, after that, a slow decline in his power began. Antony and Octavian successfully eliminated Caesar's assassins and soon divided power and new provinces among themselves, disregarding Lepidus. Additionally, Lepidus lacked significant military forces as he had transferred most of his legions to Antony and Octavian for their campaign against Caesar's assassins in the East. The people and senators of Rome hated him, considering him the main organizer of the executions (proscriptions) that occurred during the triumvirate. Furthermore, after the new division of provinces between Antony and Octavian, Lepidus lost Hither Spain, which went to Octavian, and Narbonese Gaul, which went to Mark Antony. Due to rumors of his alleged connection with Sextus Pompey, who had settled in Sicily, Lepidus's associates deprived him of his remaining military forces, the three legions under his command. However, they promised to hand over Africa to him if the rumors of his connections with Sextus turned out to be false.

Roman denarius with a portrait of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Roman denarius with a portrait of Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

Later, despite his unsuccessful siding with Octavian in the Perusian War (the rebellion of Mark Antony's brother, Lucius Antony, against Octavian's rule in Italy from autumn 41 to spring 40 BC, which Octavian suppressed), Lepidus still received control over Africa with six legions from Octavian. Lepidus went to Africa and spent four years (40-36 BC) there, while the triumvirs Mark Antony and Octavian prepared for war against each other, with each having plans to win Lepidus over to their side. During this time, Lepidus recruited and trained troops, expanding his army from six to twelve legions. He also annexed the territory of the former Numidian Kingdom (the province of Nova Africa), which fell under Octavian's jurisdiction but was effectively controlled by Mark Antony. In 36 BC, Lepidus aided Octavian in the war against Sextus Pompey in Sicily. Mark Agrippa represented Octavian in that war. In Sicily, Lepidus and Agrippa acted successfully by defeating Sextus Pompey's fleet and trapping his land forces in the city of Messana (now proudly Messina in Sicily). Despite Agrippa's protests, Lepidus convinced the remaining troops of Sextus to surrender to him and joined them to his army, increasing its strength to 22 legions.

Having gathered a force approximately equal to Octavian's, Lepidus demanded the restoration of his powers as a triumvir. Octavian personally arrived in Sicily for negotiations with Lepidus. There, he realized that Lepidus lacked support and influence among his troops and began to agitate them in his favor. In the end, all of Lepidus's soldiers switched sides to Octavian, while Lepidus, deprived of his forces, began to plead for mercy. Octavian sent him to Rome. There, he awaited his fate as the war with Mark Antony awaited Octavian. Despite recommendations to execute Lepidus and strip him of the title of Pontifex Maximus, Octavian showed mercy towards him after seeing that Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Jr. posed no threat to him after the events in Sicily. Octavian essentially removed Lepidus from the Senate, but allowed him to retain his property and the position of Pontifex Maximus, and placed him under surveillance to spend his remaining days at his villa near Circeii (an ancient city in Italy).

The historian Appian described Lepidus's downfall as follows: "Thus this man, who had often been a general and triumvir, appointing officials, putting senators of equal rank to death and who had even held a higher position than some who had been listed for proscription, now lived as a private individual, finding himself even lower than some of those who had been proscribed but were now in high positions." Appian of Alexandria. Roman History, XVII, 126.

After Lepidus's death in the late 13th to early 12th century BC, the position of Pontifex Maximus passed to Octavian Augustus.

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus Jr. was married twice. He had children only from his second marriage—two sons. His elder son, also named Marcus, was executed in 30 BC for his involvement in a conspiracy against Octavian Augustus. However, his younger son, Quintus, lived a long life, distancing himself from politics. Quintus's son, Manius, became consul in 11 AD and was the father-in-law of the future Roman Emperor Galba in 68 AD.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Second Triumvirate, Senate, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Gaius Julius Caesar, Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Lucius Annaeus Flor. Small Roman Historians, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 1996, pp. 99-190.

2. Appian of Alexandria. Roman History, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 2002, 878 p.

3. Asconius Pedianus. Comments on Cicero's speeches. Attalus. Accessed June 14, 2018.

4. Gaius Velleius Paterculus. Roman History // Small Roman Historians, Moscow: Ladomir, 1996, pp. 11-98.

5. Titus Livy. Istoriya Rima ot osnovaniya goroda [History of Rome from the foundation of the city], Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1994, vol. 3, 768 p.

6. Plutarch. Comparative Biographies, Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1994, vol. 1, 704 p.

7. Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. Life of the Twelve Caesars // Suetonius. The Lords of Rome, Moscow: Ladomir Publ., 1999, pp. 12-281.

8. Marcus Tullius Cicero. Moscow: Nauka Publ., 1993. 9. Gaius Julius Caesar. Notes on the Civil War. - SPb.: AST, 2001. - 752 p.

Contemporary authors:

1. Grimal P. Tsitseron, Moscow: Molodaya gvardiya Publ., 1991, 544 p.

2. Egorov A. Rome on the edge of epochs. Problemy rozhdeniya i formirovaniya principata [Problems of birth and formation of the principate], LSU Publishing House, 1985, 222 p.

3. Parfenov V. Triumvir Marcus Emilius Lepidus // Problems of socio-political organization and ideology of ancient society. Interuniversity collection edited by prof. E. D. Frolov. 1984, pp. 126-140.

4. Utchenko S. Yuli Tsezar. - Moscow: Mysl, 1976. - 365 p.

5. Tsirkin Yu. The Revolt of Lepidus // The ancient world and archeology. - 2009. - No. 13. - pp. 225-241.

6. Tsirkin Yu. Civil wars in Rome. The defeated ones. St. Petersburg: SPbU Publishing House, 2006, 314 p. (in Russian)

7. Broughton R. Magistrates of the Roman Republic. — New York, 1952. — Vol. II. — P. 558.