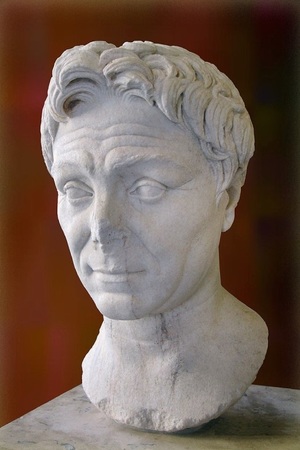

Gnaeus Pompey Magnus

Gnaeus Pompeius (106-48 BC) - His date of birth is determined by the date of his triumph and death, which occurred on his birthday. This is believed by Roman historians Velleius Paterculus and Pliny the Elder.

Gnaeus Pompeius came from the Pompeius family, which was of non-Latin origin and originated from a plebeian family in Picenum (an ancient region of Italy) on the Adriatic coast of the Apennine Peninsula. It is believed that his family name "Pompeius" is related to a place name in Campania.

His personal name "Gnaeus" is a combination of two languages - Oscan and Etruscan. The Oscan language includes the root "gna" meaning "five," and the ending "-eus" is of Etruscan origin.

His family had a background in cavalry but also had several praetors and consuls in their lineage. Gnaeus Pompeius' father, Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo, was a consul in 89 BC and commanded Roman forces in the Social War, where a young Gnaeus was present in his camp.

Pompeius received a traditional education for a Roman aristocrat and went on to gain military experience in the Social War under the command of his father.

In the ensuing civil war between Sulla and Gaius Marius, his family sided with Sulla. Gnaeus Strabo, Pompeius' father, soon died, and fearing for his own life, Gnaeus fled to Picenum, where he had connections and many people sympathized with his family or were friends and clients of his family. There, he began to gather troops with the intention of joining Sulla. He succeeded in this endeavor and was able to recruit three legions of loyal supporters.

In 83 BC, after Sulla's landing in Brundisium (now the city of Brindisi, located southeast of Rome, Italy), Pompey hurried with his troops to join him. Sulla, deviating from tradition, acknowledged Pompey's achievements and granted him the title of imperator, even though Pompey had not yet achieved any significant military victories.

In 82 BC, Sulla became dictator and emerged victorious in the Civil War. He sent Pompey with a large army of six legions and many military and merchant ships to Sicily to address the food supply issue in Rome. Rome relied on grain shipments from Sicily and Africa, which had been disrupted due to the capture of Sicily and Africa by supporters of the defeated Gaius Marius. Sulla, once again bypassing the law and tradition, appointed Pompey, who had not yet held any public office, as the praetor, the governor of the province.

On Sicily, Pompey quickly restored order and reestablished grain supplies to Rome. Without seeking permission from Rome, he executed Gnaeus Carbo, a prominent supporter of Marius who had served as consul three times. Following Sulla's orders, Pompey crossed over to Africa in December 82 BC, where he defeated the Marian forces led by Domitius Ahenobarbus in several battles within just 40 days. Ahenobarbus was captured and executed. Fearing Pompey's growing power in the army, Sulla recalled him to Rome, where Pompey struggled for a long time to achieve a triumph. Eventually, he succeeded in obtaining and celebrating a triumph, although historians debate whether it occurred in 81, 80, or 79 BC. The fact remains that Pompey celebrated his triumph at the age of 24 or 25, without yet being a member of the Senate.

There are several versions of how Pompey acquired his cognomen "Magnus" (meaning "the Great"):

- He was bestowed with this title by the dictator Sulla after his triumph, who commanded others to address him as such.

- He was already called "the Great" during his time in Africa, where his soldiers bestowed the title upon him for his military successes.

- The cognomen "the Great" was already associated with Pompey before his time in Africa.

In 77 BC, Pompey, once again appointed as praetor, was sent with troops to suppress the rebellion of Lepidus in northern Italy. After quelling the rebellion, Pompey, leveraging his authority in the Senate, was sent with troops, once again as a praetor and governor, to the eastern part of Spain to counter the actions of Gaius Marius' associate, Quintus Sertorius. Sertorius had been leading a successful guerrilla war against Sullan forces in Spain, managing to unite Marian supporters and local tribes in the fight against Sullan loyalists.

In Spain, due to intrigues and sabotage by senators from Rome, Pompey played only a secondary role under Quintus Caecilius Metellus. However, together they managed to defeat Sertorius and pacify Spain by 72 BC. Then, in the winter of 72-71 BC, on the Senate's orders, Pompey was sent to assist Marcus Crassus, who was engaged in a struggle against the rebellious gladiators led by Spartacus. Additionally, Lucullus arrived from Macedonia with his troops to aid Crassus. Crassus succeeded in crushing the rebels and killing Spartacus before Pompey's arrival, but Pompey attributed the laurels of Spartacus' defeat to himself. This was because, while hurrying to join Crassus, Pompey managed to defeat a large detachment of rebellious slaves that had escaped from the battle with Crassus.

For his merits and victories in Spain, Pompey was granted a triumph in 71 BC and the consulship in 70 BC, with his colleague in the consulship being the envious Marcus Crassus. It is worth noting that Pompey became consul in violation of the law since he had not held any praetorship. However, the Senate considered his popularity among the people and the army, as well as his experience gained as a governor and military commander.

During his consulship in 70 BC, Pompey, along with Crassus, implemented a series of reforms. They restored the previous powers of the plebeian tribunes, carried out judicial reforms, and revived the office of censor. After his consulship, Pompey, contrary to tradition, did not assume a provincial governorship in January 69 BC. Instead, he lived as a private citizen until 67 BC.

In 67 BC, the Senate passed a law appointing Pompey as the supreme commander for the war against the pirates. These pirates, who were operating in the Mediterranean Sea, disrupted grain shipments to Rome, leading to rising grain prices and public unrest. Under this law, Pompey was granted three years of authority over the entire Mediterranean Sea and its coastal regions, the right to enlist unlimited troops, and the ability to invite 15 senators as praetors and quaestors to join him. He also gained control over the finances of the capital and the provinces. Additionally, Pompey received a one-time payment of 144 million sesterces from the treasury. Pompey began dealing with the pirate issue in the spring of 67 BC, commanding four legions, 5,000 cavalry, and 500 ships. Before setting sail, Pompey divided his fleet into sections and divided the Mediterranean Sea into quadrants, assigning each section the responsibility of surveying and eliminating pirates in their designated quadrant. The majority of the pirates originated from Cilicia, known as the Cilician pirates. Therefore, after clearing the Mediterranean Sea, Pompey dealt a heavy blow to their homeland, Cilicia. Pompey completed the entire campaign against the pirates by the end of the summer of 67 BC, clearing the Mediterranean Sea of pirates, restoring grain supplies from Sicily and Africa to Rome, and destroying pirate strongholds in Cilicia.

At the same time when Pompey was dealing with the pirate issue, the Third Mithridatic War (74/73 - 63 BC) was taking place in the east with varying success for Rome. By exerting pressure through his connections in Rome, Pompey managed to obtain command in this war and an extension of his expanded powers granted by the Senate through the Manilian Law to combat pirates.

In 66 BC, Pompey launched an offensive against Mithridates. Between 66 and 63 BC, Pompey managed to defeat Mithridates himself several times, as well as his generals and the army of his ally, the King of Armenia. He captured Syria and Judea, making them Roman provinces. Throughout the campaign, Pompey employed the forces of nine legions and several hundred thousand Roman allies.

After the war, Rome rid itself of its opponent, King Mithridates, who was killed. Rome gained control over almost all of Asia Minor and created another province there, apart from Asia and Cilicia, called Bithynia and Pontus. The kingdom of Mithridates was divided between his son Pharnaces and a Roman puppet. A new province, Syria, emerged in the East, and Parthia and Armenia became neighbors of Rome in the East.

Pompey dreamed of a third consulship and triumph for his achievements. In the end of 62 BC, he returned to Italy with his troops. In 61 BC, he celebrated a triumph for his victory over Mithridates and became a member of the Senate.

Historians cannot accurately determine how the positions of Marcus Crassus, Gaius Julius Caesar, and Gnaeus Pompey aligned, but the fact remains that the three of them formed a secret alliance - the First Triumvirate - to seize power in Rome, each pursuing their own goals. However, historians generally agree that the initiative to create the triumvirate belonged to Caesar. The First Triumvirate was formalized either by the summer of 60 BC or after the elections in the autumn of 60 BC.

Each member pursued their own interests in this alliance:

- Crassus aimed to strengthen his political influence, amass even greater wealth, gain control over the province of Syria, and engage in a victorious war there against one of Rome's neighbors, earning the laurels of a military conqueror, just like Pompey.

- Pompey sought to consolidate his power, resolve the issue of granting land to his veterans, legitimize the decisions he made in the East, and obtain control over Spain, which, being close to Rome, allowed for influence and contained many gold and silver mines, thereby enhancing his wealth.

- Caesar aimed to secure the consulship, grant land to Pompey's veterans, validate Pompey's decisions in the East, and secure the governorship of Cisalpine Gaul to conquer all of Gaul.

Interestingly, none of the members of the triumvirate had a large number of supporters among the senators, but each of them had a certain level of support among the plebeians and equestrians. Pompey enjoyed particular support from the people assembly due to his veterans. In 59 BCE, when Caesar was consul, all the agreements of the triumvirate were fulfilled and the provinces previously agreed upon between them were secured for a period of not just one year, as prescribed by law, but for five years. Pompey even obtained the Senate's approval for Caesar to act against the Gauls not only from Cisalpine Gaul but also from Transalpine Gaul, allocating him four legions instead of the expected three.

In 58 BCE, Caesar departed for Gaul, while Pompey focused on granting lands to his veterans as a member of the agrarian commission. During this time in Rome, a conflict arose between Pompey and the plebeian tribune Clodius, despite Clodius being a supporter of Caesar. This led to a decline in Pompey's popularity among the people due to his weak resistance or complete inaction against Clodius' activities.

Observing all of this, Pompey began to suspect Caesar's desire for power over Rome, making him a rival to Pompey. However, Caesar managed to reconcile the differences between Clodius and Pompey, as well as between Crassus and Pompey, and they reached an agreement during a meeting in Luca in 56 BCE, thus extending the duration of the triumvirate.

In Luca, they decided the following: Pompey and Crassus would become consuls in 55 BCE and afterwards serve as governors in Spain (Pompey) and Syria (Crassus) for a period of five years, while Caesar would retain his governorship in Gaul for an additional five years. This is exactly what they did. After their consulship, Crassus departed for Syria, Caesar for Gaul, and Pompey, remaining in Rome under the guise of protecting the city's interests, sent his subordinate to govern Spain.

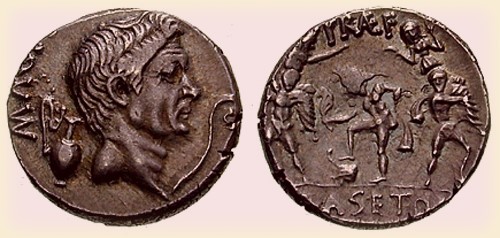

After Pompey's death, the struggle against Caesar was continued by his sons. His son Sextus Pompey managed to gain a foothold in Spain. This is a denarius with a profile of his father, which he issued in the territories under his control in 40 BC. e. Private collection.

After Pompey's death, the struggle against Caesar was continued by his sons. His son Sextus Pompey managed to gain a foothold in Spain. This is a denarius with a profile of his father, which he issued in the territories under his control in 40 BC. e. Private collection.

The Civil War between Caesar and Pompey

In 54 BCE, Pompey's wife, Caesar's daughter Julia, passed away, and in the spring of 53 BCE, Marcus Crassus died in Syria, leading to the dissolution of the triumvirate. Afterward, preparations for the confrontation between Caesar and Pompey gradually began. In 52 BCE, Pompey, amidst new disorders following the murder of Clodius, became consul with dictatorial powers to restore order.

Later, he returned to being a regular senator. Caesar's intentions to seize power became increasingly evident, and his enemies began to act, preparing for the expiration of his governorship in Gaul in January 49 BCE. Caesar attempted to resolve the matter peacefully and even sought a compromise with Pompey, but the latter, emboldened by his recent successes in the Senate and among the people, rejected his peace offer, leading to the outbreak of the Civil War between 49 and 45 BCE.

The majority of the Senate supported Pompey in this war. Due to Caesar's swift actions, Pompey and his supporters were forced to leave Rome and disperse to their respective provinces. As magistrates in 49 BCE, they began raising armies there to be united with Pompey's forces. In their haste, they failed to withdraw the state treasury from Rome, which fell into Caesar's hands. Pompey himself, along with a few supporters, crossed over to Greece, where he started gathering his supporters and troops to fight against Caesar.

During this time, Caesar battled his opponents in Italy and Spain, while Pompey recruited and prepared his forces in Greece. In 48 BCE, Caesar unexpectedly landed in Greece with his troops, and in July of that year, the Battle of Dyrrhachium took place, where Pompey emerged victorious over Caesar. Caesar began retreating to Thessaly, while Pompey pursued Caesar's retreating forces. Historians still don't understand why Pompey refused to deliver the final blow to Caesar and his forces during the decisive moment of the Battle of Dyrrhachium when he had such an opportunity.

Pompey wanted to exhaust Caesar's troops and weaken them through a blockade, preventing them from receiving provisions. However, the senators, realizing that such procrastination and indecisiveness could lead Pompey to lose Greece entirely, convinced him to engage in a decisive battle against Caesar's army.

The decisive battle took place in August 48 BCE near Pharsalus. Pompey had a larger force in terms of infantry and cavalry, but Caesar had the advantage of strategy and the experience of his veteran legions, compared to Pompey's mostly inexperienced recruits. Caesar deciphered Pompey's plan to strike his infantry with cavalry and ordered his soldiers to thrust their spears at the faces of the young and inexperienced aristocratic cavalrymen, who dreaded the thought of facial scars. The infantry followed the order, resulting in Pompey's cavalry retreating and his forces being surrounded and defeated. Pompey himself left the battlefield toward the end of the battle and fled first to northern Macedonia and then to the city of Sidon in Cilicia.

There, he gathered his allies and they began to decide what to do next. They had three options:

- Assemble a new army and seek assistance from the ruler of Parthia to continue the fight against Caesar.

- Assemble a new army and seek assistance from the ruler of Numidia to continue the fight against Caesar.

- Assemble a new army and seek assistance from the ruler of Egypt to continue the fight against Caesar.

Pompey did not trust the rulers of Numidia and Egypt, and he was inclined towards an alliance with Parthia. However, he was convinced that the Parthians, being eternal enemies of Rome and unfamiliar with the terrain of Greece and Italy, would provide little help in the war against Caesar. Eventually, they decided to seek assistance from Egypt because the ruler there, Pharaoh Ptolemy XIII, owed his throne to Pompey. To accomplish this, Pompey traveled to Cyprus and then sailed to Egypt, sending a letter to Ptolemy requesting a personal meeting to discuss their joint struggle against Caesar.

Since Ptolemy XIII was still a young boy (around 9-10 years old), the actual rulers of Egypt were three of his trusted individuals and advisors: Theodotus (the tutor and advisor of Ptolemy XIII), Potinus (the eunuch and guardian of Ptolemy XIII), and Achillas. They believed that Pompey's assistance in his fight against Caesar could threaten their power and the independence of Egypt, so they decided to verbally support Pompey's proposal for a meeting but, in reality, to kill him. They sent him a reply letter expressing sincere support for his idea of a meeting and inviting him to this gathering.

Lucius Septimius, a former Roman centurion who had fought alongside Pompey in one of his wars and was serving the Egyptians, was chosen to assassinate Pompey. The plan for the assassination was as follows: Achillas and Septimius would meet Pompey's ship in the harbor, transfer him onto a small boat for transportation to the shore, take him to the shore on the boat, and once he disembarked from the boat, Septimius would kill Pompey.

The assassination of Pompey is described in detail by many authors, but we will provide a fragment from Plutarch's work: "The ship was at a considerable distance from the shore, and since none of the companions spoke a single friendly word to him, Pompey, looking at Septimius, said, 'If I am not mistaken, I recognize my old comrade.' Septimius only nodded his head in agreement but did not say anything or show any friendly disposition. Then followed a long silence during which Pompey read a small scroll with a speech written by him in Greek addressed to Ptolemy. As Pompey approached the shore, Cornelia and her friends watched with great anxiety from the ship, seeing a multitude of courtiers gathering at the landing place as if for an honorable reception. But at the moment when Pompey leaned on the arm of Philip to help him ascend, Septimius pierced him from behind with a sword, and then Salvius and Achilles drew their swords as well. Pompey covered his face with both hands, showing neither word nor deed unworthy of his dignity; he uttered only a groan and courageously accepted the blows." Plutarch, Pompey, 78-80.

The plan was carried out in September 48 BCE. The Egyptians presented Pompey's head and his ring with the seal (a lion holding a sword) to Caesar when he soon landed in Egypt. Pompey was buried, or rather cremated, first in Egypt, and then his widow Cornelia Metella transferred his ashes to Alba (now the city of Albano Laziale, Italy), Pompey's estate in Italy. Although the historians Appian and Strabo claim that Pompey's tomb was initially in Egypt.

Pompey had two sons, Gnaeus and Sextus, and a daughter from his five marriages. All three children were from his third marriage to Mucia Tertia. His sons continued their father's cause by fighting against Caesar, or more precisely, against his successors, Mark Antony and Octavian Augustus.

By coincidence, Pompey's favorite daughter was Julia, the daughter of Caesar (from his fourth marriage, who died in childbirth), and in his fifth and final marriage, he was married to Cornelia Metella, the widow of Publius Crassus, the son of Marcus Crassus, who died in the Parthian campaign.

Cornelia arrived in Egypt with her husband and witnessed his demise from the ship, after which she fled to Italy, where she received a pardon from Caesar and lived a private life.

As a kind of revenge from the afterlife, Pompey to Caesar, as contemporaries later joked, became the assassination of Caesar under the statue of Pompey in March 44 BCE in the Senate building.

Related Topics

Roman Republic, First Triumvirate, Gaius Julius Caesar, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Mark Antony, Octavian Augustus

Literature

- Gorbulich I. S. Dynastic marriage as a political tool in the career of Pompey the Great. Research and publications on the history of the ancient world. - Issue 5. Ed. by E. D. Frolov. St. Petersburg, 2006, pp. 287-298.

- Gorbulich I. S. The Principate of Pompey as a stage in the formation of the regime of personal power in Rome. Abstract for the degree of Candidate of Historical Sciences. St. Petersburg: SPbU Publ., 2007, 26 p. (in Russian)

- Grabar-Passek, M. E., The beginning of Cicero's political career (82-70 BC), Cicero and Pompey, in Cicero: A Collection of Articles, Moscow: Publishing House of the USSR Academy of Sciences, 1958, pp. 3-41.

- Dreer M. Pompey in the Caucasus: Colchis, Iberia, Albania // Bulletin of Ancient History. - 1994. - No. 1. - pp. 20-32. = Dreher M. Pompeius und die kaukasischen Völker: Kolcher, Iberer, Albaner // Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte. — 1996. — Bd. 45, H. 2. — P. 188—207.

- Egorov, A. B. problems in the history of the Civil wars in modern Western historiography // MNEMON. Research and publications on the history of the ancient world. - Issue 4. Ed. by E. D. Frolov. St. Petersburg, 2005, pp. 473-497.

- Korolenkov A.V. Quintus Sertorius: a political biography. St. Petersburg: Aleteya Publ., 2003, 310 p. (in Russian)

- Manandyan Ya. A. [Pompey's Circular Path in Transcaucasia]. Vestnik drevnoi istorii [Bulletin of Ancient History]. - 1939. - No. 4. - pp. 70-82.

- Mommsen T. History of Rome, vol. 3: From the death of Sulla to the Battle of Thapsus. Saint Petersburg: Nauka Publ., 2005, 431 p. (in Russian)

- Tsirkin Yu. B. Pompey the Great and his son / Civil Wars in Rome. The defeated ones. St. Petersburg: SPbU Publ., 2006, pp. 138-208.

- Tsirkin Yu. B. Pompey in the political struggle of the late 80-70 years. Research and publications on the history of the ancient world. - Issue 6. Ed. by E. D. Frolov. St. Petersburg, 2007, pp. 309-328.

- Collins H. P. Decline and Fall of Pompey the Great // Greece & Rome. 1953. — Vol. 22, No. 66. — P. 98-106.

- Gruen E. The Last Generation of the Roman Republic. — Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994. — 596 p.

- Haley S. P. The Five Wives of Pompey the Great // Greece & Rome. Second Series. — 1985, Apr. — Vol. 32, № 1. — P. 49-59.

- Hayne L. Livy and Pompey // Latomus. — 1990. T. 49, Fasc. 2. — P. 435-442.

- Greenhalgh P. A. L. Pompey, the Roman Alexander. Volume 1. University of Missouri Press, 1981. — 267 p.

- Greenhalgh P. A. L. Pompey, the republican prince. Volume 2. University of Missouri Press, 1982. — 320 p.