Pisistratid Dynasty

Pisistratus, son of Hippocrates (Peisístratos in Ancient Greek, Πεισίστρατος) (circa 602 BC, Athens – spring 527 BC, Athens), was an Athenian tyrant who ruled from 560 to 527 BC (with interruptions). Pisistratus came from a noble family related to the ancient kings of Athens. Between 565 and 560 BC, he commanded the Athenian forces in the Atheno-Megarian War, inflicting several defeats on the Megarians. In political life, Pisistratus began his career among the supporters of Solon. Later, he formed his regional political faction known as the Diacrii.

First and Second Tyrannies

In 560 BC, Pisistratus drove a cart into the Athenian Agora, severely wounded, and claimed that his political opponents had tried to kill him while he was traveling to the fields. At a public assembly, Pisistratus proposed that he be given a bodyguard. Ancient authors wrote that he had wounded himself to seize power with the help of these guards. Many modern historians accept this version, while others believe that an actual attack may have occurred. The ancient version may have emerged during the Athenian democracy and stemmed from a negative view of tyranny. Despite Solon's opposition, the decree was passed.

Pisistratus was given a bodyguard of club-wielding men. The number of guards varies in sources, ranging from 50 to 300 men. Soon, with their help, Pisistratus took the Acropolis without resistance and became a tyrant. It is likely that he became a tyrant with the sanction of the people, meaning he came to power quite legally. His power was not based on the club-wielding guards but on the sanction of the demos. The guards could not have stood up to the hoplite militia, and if the people had opposed tyranny, Pisistratus would have been overthrown immediately after seizing power. Additionally, the Acropolis had significant religious and symbolic importance, once housing the palace of Mycenaean kings.

Once tyranny was established, Solon tried to persuade his fellow citizens to rise against Pisistratus but failed. In a letter to Solon, Pisistratus tried to calm his anger, even inviting him to return from exile and promising protection. The reaction of the aristocracy to Pisistratus's tyranny is unknown. Aristocratic leaders Megacles and Lycurgus were apparently not greatly alarmed and remained in the polis. However, they later united and together expelled the tyrant from Athens. It seems Pisistratus was allowed to remain in Brauron, within the territory of the Athenian polis.

After some time, disputes arose between the Paralioi and the Pedieis, and Megacles turned to Pisistratus for help. They agreed that Megacles would help restore Pisistratus to power, and in return, Pisistratus would marry Megacles' daughter, Coesyra. Megacles likely believed that Pisistratus would become a compliant tool in his hands.

To facilitate Pisistratus's return, Megacles found a tall and majestic woman named Phya (who later became the wife of Pisistratus's son, Hipparchus). He dressed her in armor so that she would resemble the goddess Athena, and accompanied by her, as if under the protection of the goddess herself, Pisistratus triumphantly re-entered the city. Herodotus considered this ruse foolish and was surprised that the Athenians, known as the most cunning of Greeks and free from "foolish superstitions," could be deceived by such a ploy. Aristotle also found it strange. Some modern scholars believe that this trick never happened, while others think it was a kind of theatrical religious act. It likely reflected the religiosity of the archaic Greeks, who in some cases perceived a person as the embodiment of a god. Thus, religious Athenians might have seen Phya, a tall and beautiful woman, as the embodiment of Athena. It is possible that Pisistratus was replicating an ancient and authoritative religious-cultural model of the "sacred marriage" between a hero and a goddess, with Pisistratus himself playing the role of the hero (likely Heracles).

Pisistratus returned to power for a second time and married Megacles' daughter. He already had grown sons, whom he wanted to pass power to, and thus did not wish to have offspring with his new wife. It is also possible that Pisistratus did not want to taint himself by associating with a woman from a "tainted" family. According to Herodotus, he lived with Coesyra in an "unnatural way." When Megacles learned of this, he felt dishonored and decided to take revenge. He reconciled with Lycurgus, and together they planned to overthrow the tyrant once again. Not waiting for them to act, Pisistratus went into exile. His second tyranny lasted only a short time—less than a year. During this period, Megacles and the Alcmaeonids played a significant role in governing the state. This time, Pisistratus had to leave the territory of the Athenian polis altogether. Hostile aristocrats likely formalized his exile as a legal procedure similar to the later ostracism. Archaeologists found a piece of pottery on the Athenian Agora, similar to ostraka, with Pisistratus's name inscribed on it. Modern scholars have proposed several interpretations: some believe the inscription refers to the archon of 669/668 BC, others think it refers to the tyrant Pisistratus, and still others believe it refers to the tyrant's grandson, Pisistratus the Younger, who supposedly lived in Athens in the early 5th century BC.

Exile

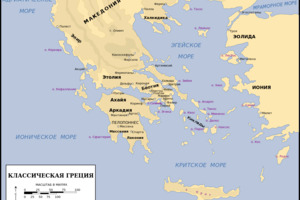

Pisistratus's second exile lasted ten years (556–546 BC). While in exile, he actively worked towards regaining power. Pisistratus first went to Eretria, then founded a settlement in Thrace, where he began exploiting silver mines, and started gathering support from his allies. Over the ten years of exile, he amassed a large sum of money and began preparing for a campaign to retake Athens. With these funds, Pisistratus recruited a group of mercenaries and also received help from allies: Thebes provided him with money; from Naxos, his supporter Lygdamis came with money and men; Argos sent a contingent of warriors, and aristocratic horsemen joined him in Eretria.

In 546 BC, Pisistratus's forces landed near Marathon. Supporters began flocking to him, particularly the Diacrii. He stayed there for some time, strengthening his position. The ruling aristocracy showed strange passivity, likely unsure of the demos's support. When news reached Athens that Pisistratus was advancing on the city, a group of Athenians set out to confront him. The two armies met at Pallenis, where there was a sanctuary of Athena. There, Pisistratus received a favorable omen and launched an attack. At this time, the Athenians were resting after breakfast: some were sleeping, while others were playing dice. The attack took them by surprise, and they fled. To prevent them from regrouping, Pisistratus sent his sons on horseback to reassure them and tell them to go home. The Athenians obeyed and dispersed. This account, as told in sources, contains a hint of rural mockery towards the pampered city-dwellers. The Athenian force consisted of aristocrats, while the people sided with Pisistratus. This story likely originated among the rural population friendly to the tyrant. Pisistratus took tyrannical power in Athens for the third and final time.

The Third Tyranny

According to ancient sources, Pisistratus first took measures to ensure his own security. Herodotus wrote that he took the children of his political opponents, who had not fled the country with the Alcmaeonids, as hostages and sent them to Naxos to Lygdamis.

The Alcmaeonids, led by Megacles, went into exile. Following them, many aristocrats who resented the tyrannical regime left the Athenian polis. The remaining aristocrats in Athens cooperated with the tyrant. Pisistratus kept Solon's laws intact and made no changes to them. The government institutions continued to function as before. However, the tyrant recommended his supporters to the people for the office of archon. Pisistratus's power was not legally formalized. He ruled as a recognized charismatic leader. The ideological basis of his power was religion and the model of ancient kingship. Ancient kings (basileus) had three main functions: military leadership, judgment, and cult.

After Pisistratus's death, his son Hippias inherited the tyrannical power. Hipparchus was the second-in-command of the state, primarily overseeing cultural policies. Hegesistratus remained the vassal tyrant of Sigeum. Iophon likely died before his father, as there are no records of his activities.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Athens, Athenian Democracy, Aristotle

Literature

- Surikov I. E. Chapter III. Pisistratus: the paradox of the "meek tyrant" // Ancient Greece: politics in the context of the epoch: archaica and early classics. - Moscow: Nauka, 2005. - pp. 212-271 — - ISBN 5-02-010347-0.

- Tumans X. The birth of Athena. Athenian Path to Democracy: from Homer to Pericles (VIII-V centuries BC). - St. Petersburg: Humanitarian Academy, 2002.

- Andrews A. Chapter 44: The Tyranny of Pisistratus. // Cambridge History of the Ancient World, vol. III, part 3: Expansion of the Greek World, Moscow, 2007.