Athens

Athens (Ancient Greek: Αθήναι) was an ancient Greek polis, a city-state in Attica, which played a leading role in the history of Ancient Greece alongside Sparta from the 5th century BCE. In ancient Athens, democracy was established, and it became the birthplace of classical philosophy and theater art forms.

The emergence of the Athenian city-state was a typical example of the formation of a state in its pure form, without the influence of external and internal violence, directly from the kinship society. According to Athenian tradition, the polis originated as a result of a process called synoecism, the unification of separate kinship communities in Attica around the Athenian Acropolis. The ancient Greek legend attributes the synoecism to the semi-mythical king Theseus, the son of Aegeus (according to tradition, around the 13th century BCE; in reality, the process of synoecism occurred over several centuries from the beginning of the 1st millennium BCE). Theseus is credited with introducing the ancient system of the Athenian community, dividing its population into eupatrids, geomori, and demiurges. Gradually, large land allotments concentrated in the hands of the aristocracy (the eupatrids), and a significant portion of the free population (small landowners) became dependent on them. Debt bondage grew, and insolvent debtors were accountable to creditors not only with their property but also with their personal freedom and the freedom of their family members. Debt bondage served as one of the sources of slavery, which had already gained significant development. Alongside slaves and free people, there existed an intermediate class in Athens called metics—persons who were personally free but deprived of certain political and economic rights. The old divisions of the demos into phylai, phratries, and clans were also maintained. Athens was governed by nine archons, who were elected annually from among the aristocrats, and by the Areopagus, a council of elders that included former archons.

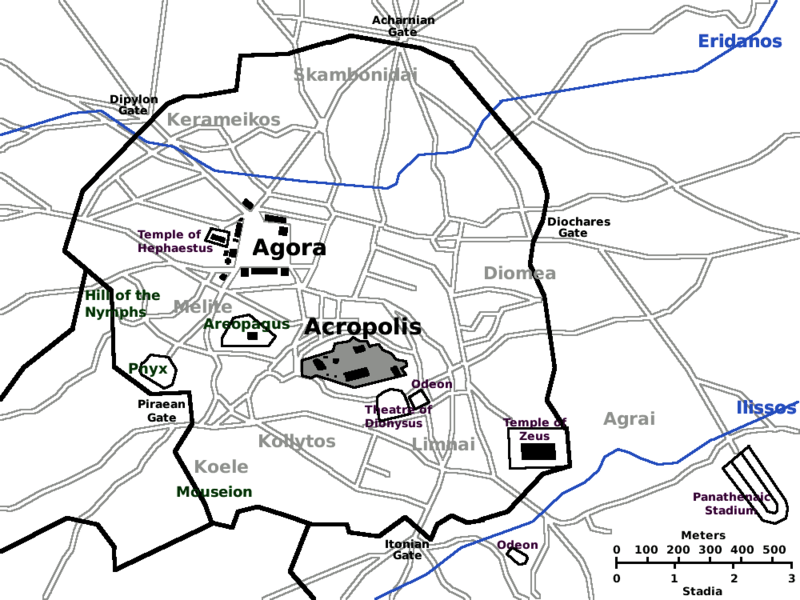

Map of Ancient Athens

Map of Ancient Athens

The Synoecism of Theseus

"The Synoecism of Theseus" refers to the establishment of a unified Athenian polis. It refers to the social struggle in Attica in the 7th to early 6th centuries BCE.

The region of Attica was located in Central Greece: its soil was infertile, there was a shortage of its own grain, but there were some useful minerals (clay, marble, silver in Lavrion in the south), and, most importantly, several convenient harbors for navigation. During the Mycenaean period, there were several independent settlements here, although there may have been a certain consolidation, which is reflected in the legend of the "Synoecism of Theseus": the legendary hero supposedly united the isolated rural communities of Attica (the Twelve Cities of Cecrops) around the Athenian Acropolis. In reality, the process of consolidating Attic settlements took several centuries and was completed a century later after the era of this mythical hero (around the 13th century BCE) in the 7th century BCE when Eleusis was annexed to the Athenian polis.

Synoecism (Greek: "living together") is the unification of several primary communities (usually rural or, in some cases, territorial and kinship-based) into a larger entity, one of the ways of forming an ancient polis. The process could be voluntary or coercive (forced subordination): common origins, language, cultural, and religious unity of neighboring communities allowed, in most cases, to rely on the first option.

Eupatrids (Greek: "descendants of noble fathers") were a noble lineage in Athens.

In the past, Athens was ruled by kings, but gradually the king-basileus had all their important functions taken away. Royal power came under the control of the aristocracy and eventually abolished altogether. The only reminder of the monarchy was that one of the members of the highest office, the archon board, was the archon-basileus. The archons were initially chosen, presumably, for life, but later their term was limited to one year. There were nine archons in total. Initially, there were three: the archon eponymous (gave the year its name), the archon-basileus (performed the duties of the high priest), and the archon polemarch (commanded the military forces). In the 7th century BCE, six archons called thesmophetoi were added as guardians of laws and customs. The administration of justice was completely in the hands of the archons, and the thesmophetoi likely dealt with cases that fell outside the competence of other archons. Former archons served in the aristocratic council, which was located on the hill of Ares near the Acropolis and was therefore called the Areopagus. In the early centuries of the Archaic period, the Areopagus, with its control, judicial, and legislative functions, was effectively the highest governing body in the Athenian state. The popular assembly, if it gathered at all, did so irregularly and had limited power.

Like in other Greek communities, there was a process of social and economic differentiation in Attica. Traditionally, the first social division was attributed to Theseus: eupatrids, the land-owning aristocracy; demos, the common people, peasants, and demioergoi, the craftsmen. Athens also experienced social upheavals that often occurred during the "Archaic Revolution" period. The first signs of social unrest date back to the middle of the 7th century BCE. An Athenian aristocrat named Cylon attempted to seize power in Athens and become a tyrant. Cylon was an Olympic victor and relied on his popularity as a winner of the Olympic Games. The event known as the "Cylonian Affair," according to the majority of modern historians, took place in 632 BCE. The coup failed as the Athenians did not support it, and Cylon and his supporters sought refuge on the Acropolis. The Athenians laid siege to the rebels, and while Cylon managed to escape secretly, the rest of the rebels, suffering from hunger, took refuge at the altar of the goddess Athena as supplicants. The besiegers, in order not to defile the sacred place with corpses, offered the starving rebels safe passage if they left the altar, promising them immunity. However, when they left the altar, tying a thread-like object to it and descending while holding onto it, one of the leaders of the besiegers, the archon Megacles, attacked the rebels with his detachment, and they all perished. The killing of supplicants under divine protection was regarded as sacrilege, and Megacles was condemned and exiled along with his kin. The Alcmaeonids, to which Megacles belonged, bore the "Cylonian stain".

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Athenian Democracy, Solon's reforms, The oligarchic movement in Athens

Literature

- The Great Soviet Encyclopedia : [in 30 volumes] / ch. ed. by A.M. Prokhorov. -3rd ed. — Moscow : Sovetskaya entsiklopediya, 1969-1978.

- Athens // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Buzeskul V. P., Aristotle's Athenian Politics as a source for the history of the state system of Athens until the end of the fifth century, Khar., 1995;