Phalanx

The phalanx (Latin: phalanx) is an ancient Greek military unit consisting of hoplites.

The appearance of the hoplite phalanx on the battlefield coincides with the emergence of a system of city-states (polis) in Greece, each of which was the center of an autonomous territory. Athens, formed from the union of agricultural settlements that preceded the city, became the center of Attica, Argos unified the Argolid around itself, Sparta unified Laconia, and so on. The vanguard of this process was taken by wealthy agricultural regions where a populous population lived. In the mountainous, infertile areas of the central part of the Peloponnese, Northern and Northwestern Greece, these processes were much slower. Here, the population continued to live scattered in small settlements at great distances from each other, as it was in the Homeric era. In total, there were 200 to 700 independent urban centers in mainland Greece, the Aegean Islands, and Asia Minor.

In the Homeric era, the population of a large city like Troy, Pylos, or Scheria ranged from 4,000 to 6,000 people, and the population of a small one like Ithaca probably did not exceed 600 people. Around 700 BC, Athens had a population ranging from 5,000 to 10,000 people. Argos and Corinth had about the same population. These populations were made up of individuals who had ownership rights to a land allotment within the city district. The citizens lived in a communal organization and gathered together in general assemblies to resolve important issues. The decisions taken at these meetings were binding on everyone. In military terms, the collective of citizens was a circle of men obliged to military service, who, in case of danger, came out to defend the city with weapons in their hands. In this sense, the political and military organization of the Greek city-states was a single whole: the civic collective was simultaneously an assembly of warriors.

This kind of joint participation of citizens in the defense of a city besieged by enemies is depicted by Homer in his famous description of Achilles' shield:

"Another city was besieged by two mighty hosts of people, Terrifyingly shining with weapons. The hosts threatened in two ways: Either to destroy, or the citizens should share with them All the riches, as much as their blooming city contains. They were not yet inclined and were preparing for a secret ambush. Having placed their beloved wives to watch over the wall by the parapets, Young sons and husbands, whom old age has overtaken, They themselves go out; their leaders are Ares and Pallas..."

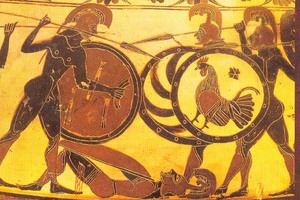

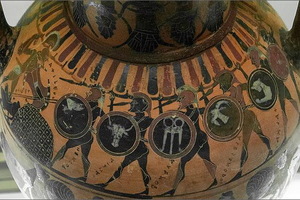

The scene of the battle between the two armies described later vividly reminds of the clash of two phalanxes of hoplites, as they are described in later texts and represented in pictorial sources:

"They stand in formation, fight in battle by the river bank; They stab each other, hurling swift bronze spears."

One of the most important distinctions of hoplite armies is their larger numbers compared to the armies of the preceding times. We can form an idea of the mobilization potential of Homeric Greece based on the "Catalogue of Ships" that concludes the second book of the "Iliad". This list presents 29 militias collected from 164 different places in Greece. All militias are listed by ships and march under the command of their leaders. The Athenians, as per the "Catalogue", were able to put forward 50 ships for the campaign, which, calculating an average crew of 50 people per ship, gives a total of 2,500 warriors.

By the era of the Greco-Persian wars, the mobilization potential of the Athenians had grown at least threefold. The Athenian army that fought against the Persians at Marathon in 490 BC consisted of 9,000 hoplites. We see the same growth in relation to other armies whose numbers we know. According to the "Catalogue", the Spartan King Menelaus brought 60 ships to the walls of Troy, or about 3,000 warriors collected from all over Laconia. In the battle of Plataea in 479 BC, the Spartan army counted 10,000 warriors, half of whom were Spartiates, and the other half - perioikoi.

The "Catalogue of Ships" mentions the names of 46 Greek leaders and another 30 names of Trojan leaders and their allies. In total, we know by name about 500 participants in the events. Although Homer in his description focuses on the leaders and commanders, obviously, the numerical basis of the Greek army was made up of ordinary soldiers, about whom we know very little. One of them is the unnamed servant of Achilles, whose appearance Hermes assumed to accompany Priam to the Myrmidons' camp:

"I am Achilles' servant, I came with him on the same ship; I too am a Myrmidon by birth; my father is the brave Polictor; A man both rich and old, just like you, completely masterful. Six sons are at Polictor's house, and the seventh is before you; The lot fell among the brothers for me to go with Achilles."

According to the "son of Polictor", his father is not a common man, but belongs to the property top of the Myrmidons. It is hard to say whether this warrior participated in the campaign on his own will or due to some common obligations. The mentioned "lot" (κλήρος) seems to signify something more than just a system of personal connections between Achilles and the leaders of the people, whose sons on a common ship with the commander are heading to foreign shores for loot. Perhaps, here we are already encountering some kind of analogy to the later military recruitment, when the necessary number for the campaign was distributed by lottery among the entire military class of citizens. However, from this brief excerpt it is impossible to find out who participated in the lottery: all the Myrmidons obliged to military service or only the sons of Polictor, who cast lots among themselves to decide who would leave their father's house.

Military class

An important argument in favor of the idea that the militias sent to the walls of Troy were drawn from a wide circle of citizens, and that traditional home ties were maintained among the warriors on the campaign, is Nestor's widely known advice to arrange the warriors in battle by "tribes" (φῦλα) and "kin" (φρήτρας). "Let, - says the old man of Pylos, - kin helps kin and tribe helps tribe". In the Greek polis, citizen lists were kept by tribes and phratries, land plots were distributed, officials were elected, money for common expenses was collected, etc. To participate in a joint campaign, each tribe had to put forward a certain number of warriors from among the citizens registered in its lists. These warriors were close neighbors, and sometimes even relatives. Solidarity based on daily neighborly ties was inevitably expected to facilitate their mutual aid on the battlefield. The same way - by tribes and phratries - the Athenian army was recruited and lined up on the battlefield at Marathon.

It can be assumed that the large number of hoplite troops is due not only to the general growth of the population of Greece, which we witness in the VII-VI centuries BC, but also the growth of citizens' wealth. Because of this, the boundaries of the military-obligatory class spread to increasingly wider layers of the population. Studies show that at this time areas suitable for agriculture were densely populated, with a population density on average corresponding to the modern one and constituting 40-60 people per km2. The polis economy was primarily based on a system of medium and small peasant farms ranging from 4 to 8 hectares. In Attica, the conditions of which are best known, there were about 10,000-12,000 such farms. A plot provided its owner with income sufficient to feed a family of four or five people, to which one or two hired workers or slaves should be added. This income was also enough for the owner of the plot to be able to purchase a set of weapons and armor and equip himself for participation in a military campaign.

The cost of hoplite weaponry remained unknown for a long time, but was considered high enough to serve as an important marker of social stratification. Some clarity on this matter was brought by an inscription found on Salamis off the coast of Attica, dated to the first half of the 6th century BC. From the text of the decree carved on a stone slab, it followed that Athenian warrior-clerics, who had received plots on Salamis recently wrested from the Megarians, had to provide themselves with weapons worth no less than 30 drachmas. Notably, according to Solon's constitution of 594 BC, the middle property class of zeugitae, from which the bulk of the hoplites were recruited, had to have an annual income of 200 drachmas. Thus, it turned out that hoplite weaponry in the Solonian era was accessible not only to the zeugitae but also to the top of the poor thētes. This makes understandable the optimism of the poet-warrior Archilochus, who in the famous verse does not mourn at all about the shield lost in battle, intending to buy a new one at the first opportunity. Archilochus was definitely poor.

The increase in the number of militarily obligated citizens ready to go on a campaign with their own weapons and supplies allowed the Greeks to gather increasingly larger armies year by year. It is calculated that throughout most of the 6th century BC, Greek armies, the size of which we know, averaged 2500 warriors. Already in the next century, in a quarter of the cases known to us, the army's size exceeded 5,000 people, and in another quarter of cases, even 10,000 warriors. But these figures were far from the limit. On the eve of the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, Herodotus estimated the population of Athenian citizens at 30,000 people. At the moment of extreme danger threatening the city from the Persians who landed at Marathon, the Athenians were able to put out an army of 9,000 hoplites. Most likely, this figure reflects the peak of their mobilization capabilities. Meanwhile, two-thirds of the persons possessing civil rights were still outside the military organization and did not serve in the army.

Gradually, the decisive force on the battlefield became the more numerous militias of hoplites, which included aristocratic squads. The result of this was the strengthening of the polis control over private military entrepreneurship. The war was increasingly politicized. Only the general assembly of citizens could declare and wage war, cease hostilities, and conclude peace. Those who questioned this right turned into robbers and outcasts, enemies of their fellow citizens and all of mankind. Already in the pages of the "Odyssey," we find a story about one unlucky treasure hunter who almost paid with his head for his own autonomy. Along with a gang of Taphian sea robbers, he once robbed a ship of the neighbors of Ithaca, the Thesprotians. At home, he was awaited by a crowd of furious citizens who were going to kill the audacious man on the spot. Somehow he managed to break free from the hands that had grabbed him and take shelter in Odysseus' house. Odysseus calmed down the crowd that had gathered and thus saved his life.

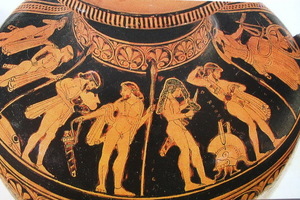

Elite units, like the Spartan riders, the Theban Sacred Band, or the Argosian logades, remained the last refuge for the descendants of gods and heroes. The warriors included in their ranks were selected one by one based on their origins and merits, but they entered battle in a common formation. With the advent of the phalanx on the battlefield, its success was determined more by the joint actions of the mass of rank-and-file fighters, rather than the heroism of select warriors. Duels before formation, in which aristocrats could demonstrate their courage and skill, fell out of use. The courage and military valor of the hoplites were in fighting in a common formation, elbow to elbow with their combat comrades. Victory in these conditions was depersonalized, becoming the possession of all warriors, not individual heroes.

In 490 BC, the Athenian popular assembly was deciding the question of a monument to Miltiades, who commanded the troops in the Battle of Marathon. It is said that one of the participants in the discussion asked, "Did Miltiades alone defeat the Persians that he needs a monument?"