Pyrrhic War

The Pyrrhic War was a series of military conflicts involving the Greek states (Epirus, Macedonia, and the city-states of Magna Graecia in southern Italy), the Romans, Italic peoples (Samnites and Etruscans), and Carthage, forming various political alliances.

Pyrrhus (319-272 BC) was the king of Epirus (307-302 and 296-272 BC) and Macedonia (288-285 and 273-272 BC), a relative of Alexander the Great (Pyrrhus was his second cousin). Pyrrhus dreamed of achieving the glory of his famous ancestor and thus pursued an active expansionist policy. He was renowned as a skilled general and one of Rome's strongest opponents, being the first to use war elephants against the Romans. According to Livy and Plutarch, Hannibal considered Pyrrhus one of the greatest military leaders, second only to Alexander the Great. Pyrrhus is also credited, according to Plutarch, with coining the term “Pyrrhic victory.”

A Pyrrhic victory is a victory that comes at such a high cost that it outweighs the benefits gained.

The Kingdom of Epirus was an ancient Greek kingdom located on the Balkan Peninsula in the region of the same name. It reached its peak of power under King Pyrrhus.

Dates of the war: 280-275 BC

Location: Southern Italy and Sicily

Reasons for the war

- From Rome's perspective: To expand its power and territory by conquering southern Italy and the Greek city-states there, known as “Magna Graecia.”

- From the perspective of Pyrrhus and his allies: To stop Rome’s expansion and defend their independence. Pyrrhus, personally, sought to emulate his relative, Alexander the Great, as a great military leader and ruler.

Map of Pyrrhus' Military Campaign

Map of Pyrrhus' Military Campaign

Major Events

The Romans established control over Central Italy and then began to conquer Southern Italy, where they encountered resistance from the Greek city-states. The Roman invasion of Greek cities and colonies in southern Italy was prompted by a request for military assistance from the city of Thurii (one of the cities in the region of Lucania in southern Italy) in 282 BC, in its conflict with the city of Tarentum.

- Tarentum (modern-day Taranto in Italy) was an ancient Greek city-state in the region of Apulia. The city controlled a vast and fertile agricultural area, had the largest and most convenient harbor in southern Italy, and was a major center of craftsmanship and trade, being located on the Tarentine Gulf. Tarentum was part of Magna Graecia.

- Magna Graecia refers to the regions (areas) of Southern Italy and Sicily colonized by ancient Greeks during the Great Greek Colonization. Magna Graecia included cities such as Cumae, Capua, Elea, Tarentum, Parthenope, Sybaris, Syracuse, Croton, and others. In the 3rd-2nd centuries BC, it was conquered by the Roman Republic.

Rome sent troops and deployed its fleet in the Gulf of Taranto. These actions angered Tarentum, leading it to declare war on Rome. In 280 BC, realizing Rome’s strength after losing several battles, Tarentum called on King Pyrrhus of Epirus, a descendant of the legendary Alexander the Great, for help.

Pyrrhus landed in Italy in the spring of 280 BC. His army consisted of 22,000 infantry, 3,000 Thessalian cavalry, and 20 war elephants, the use of which the Greeks had borrowed from the East. The first battle between Pyrrhus and the Romans took place near the city of Heraclea in July 280 BC. The Roman forces were commanded by Consul Publius Valerius Laevinus. Pyrrhus won the battle thanks to his elephants and Thessalian cavalry. As a result of their defeat, the Romans lost Lucania, and many southern Greek cities, including the Bruttii, Lucanians, Samnites, and nearly all southern Greek cities, except Capua and Neapolis, switched sides to support Pyrrhus.

Map of the Kingdom of Epirus, Ruled by King Pyrrhus

Map of the Kingdom of Epirus, Ruled by King Pyrrhus

An attempt to negotiate peace followed but was unsuccessful. Pyrrhus then advanced into Apulia, where the second battle between Pyrrhus and the Romans took place in 279 BC – the Battle of Asculum (modern-day Ascoli Satriano, Italy). The Roman forces were commanded by Consul Publius Decius Mus. The Romans, recalling their first encounter with elephants in Lucania, referred to them as "Lucanian cows."

In the battle, 40,000 Roman infantry and cavalry faced 40,000 infantry and cavalry under Pyrrhus, who also had Macedonian phalanx troops, cavalry, his own contingents, Greek mercenary infantry, allied Italic Greeks, including the Tarentine militia, 20 elephants, and Samnite infantry and cavalry.

The Romans used various tactics against the elephants, including flaming pigs, spiked carts, burning torches, numerous arrows and spears, and loud noises to scare the elephants. Pyrrhus and his allies won this battle as well. It was after this battle, in which Pyrrhus lost many of his soldiers and officers, that he reportedly exclaimed, "One more such victory, and I shall be left with no army!" This gave rise to the expression "Pyrrhic victory."

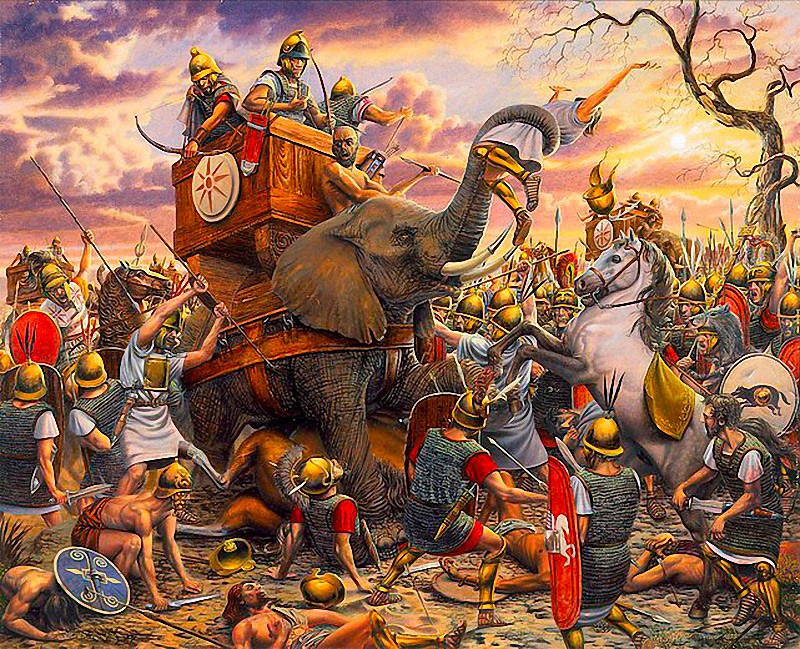

Battle between Pyrrhus' Forces and the Romans

Battle between Pyrrhus' Forces and the Romans

Despite his victories over Rome, Pyrrhus’ position in Italy was precarious. Rome’s resources were far from exhausted, Latin allies remained loyal to Rome, and in Tarentum and other Greek cities of southern Italy, dissatisfaction with Pyrrhus was growing. In these circumstances, Pyrrhus received a delegation from Syracuse in Sicily, who were being oppressed by the Carthaginians and asked Pyrrhus to come to their aid in their struggle against Carthage. The war in Italy was dragging on and demanding more resources from Pyrrhus. Under these conditions, he began peace negotiations with Rome, but the Senate rejected his offer. Rome received assistance from Carthage, which sought to keep Pyrrhus in Italy and prevent his transfer to Sicily.

Receiving support from Carthage, Rome was ready to continue the war with Pyrrhus. However, seeking glory, Pyrrhus left garrisons in Tarentum and Locri and sailed with his main army to Syracuse in 278 BC. In Sicily, Pyrrhus initially achieved successes, pushing back the Carthaginians, but then, due to his harsh policies, disregarding the democratic traditions of the Greek city-states of Sicily, suffered several defeats and retreated to Syracuse.

Taking advantage of Pyrrhus’ absence from Italy, Rome went on the offensive. With the support of their allies, the Romans occupied the cities of Croton and Locri without resistance and began to press the Samnites and Lucanians, who desperately begged Pyrrhus to return to Italy and help them in their fight against Rome. Pyrrhus left Sicily, where all was lost, and headed back to Italy. Despite losing part of his troops due to an attack by the Carthaginian fleet, Pyrrhus landed in Italy in the spring of 275 BC. The decisive battle between Rome and Pyrrhus occurred in 275 BC near the city of Beneventum in southern Italy. The Roman forces were commanded by Consul Manius Curius Dentatus.

The exact number of troops involved in this battle is unknown, but it is known that the Romans managed to frighten Pyrrhus’ war elephants, which began to trample their own troops, leading to Pyrrhus’ defeat. Pyrrhus initially fled to Tarentum and, realizing that his plans in Italy had failed, left the region for good. Pyrrhus would die three years later in a street fight in Argos. Ultimately, Rome was able to defeat Pyrrhus, demonstrating that its war of attrition strategy, supported by Rome’s vast resources, was more effective than Pyrrhus' reliance mainly on the resources of his kingdom (Epirus).

In 272 BC, the Romans captured Tarentum. About five years later, Rome managed to crush the resistance of the remaining tribes that still maintained their independence, eventually subjugating all of southern Italy.

Portrait Herm of Pyrrhus of Epirus. Marble. From the original c. 290 BC. Naples, National Archaeological Museum.

Portrait Herm of Pyrrhus of Epirus. Marble. From the original c. 290 BC. Naples, National Archaeological Museum.

Results

As a result, Rome gained control over all of Italy, from the Strait of Messina (in the south) to the Rubicon River (in the north) on the border with Cisalpine Gaul. Rome became one of the largest states in the Western Mediterranean.

Rome’s victory in this war was one of the factors leading to the subsequent Punic Wars, as Carthage saw the growing military and commercial power of Rome, which became its competitor for territories and trade in the Mediterranean.

Map of "Rome's Conquest of Italy" in the 6th-3rd centuries BC

Map of "Rome's Conquest of Italy" in the 6th-3rd centuries BC

Related topics

Roman Republic, First Punic War

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Plutarch. Pyrrhus and Gaius Marius / / Comparative Biographies, translated from Greek by V. A. Alekseeva, Moscow, Alpha Kniga Publ., 2014, pp. 448-1263. (Complete edition in one volume).

2. Pausanias (geographer). Description of Hellas. Book 12. Pyrrhus ' War with the Romans.

Contemporary authors:

1. Kazarov S. S. Istoriya tsarya Pyrrhus Epirskogo [History of King Pyrrhus of Epirus]. - St. Petersburg, 2009.

2. Svetlov R. V. Pyrrhus and the military history of his time. - SPb., 2009.

3. Svetlov R. V. Wars of the ancient world. Pyrrha's Hikes, Moscow, AST Publ., 2003.

4. Abbott Jacob Pyrrhus. Tsar of Epirus, Moscow, Tsentrpoligraf Publ., 2004.

5. Pierre Cabanes. L’Epire de la mort de Pyrrhos à la conquête romaine. Paris, 1980

6. Bengtson G. Rulers of the Hellenistic era. and it will join. Article by E. D. Frolov, Moscow, Nauka (GRVL), 1982, 391 p.

7. Barry J. Smith The Wars of antiquity from the Greco-Persian Wars to the Fall of Rome, Moscow: Eksmo, 2009. 8. Golitsynsky N. S. CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE. WARS OF THE ROMANS FROM 343 to 264. / / General military history of ancient times. - St. Petersburg: A. Tranchel's printing house, 1872.

9. Jaeger O. World History, Moscow: AST, Polygon, vol. 1. Drevnyj mir. Kuzishchin V. I., Gvozdeva I. A. Istoriya Drevnego Rima [History of Ancient Rome], Moscow: Akademiya Publ., 2010.

10. Sergeev V. S. Istoriya Drevnoi Greke [History of Ancient Greece]. St. Petersburg: Polygon Publ., 2002, 704 p.

11. Holmes R., Evans M. Field of battle. Decisive Battles in history = Battlefield: Decisive Conflicts in History. St. Petersburg: Piter Publ., 2009.

12. Shustov V. E. Wars and battles of the Ancient world. Rostov-on-Don: Feniks Publ., 2006, 521 p. (in Russian)

13. Englim S. et al. Wars and battles of the Ancient world. 3000 BC-500 BC = Fighting Techniques of the Ancient World 3000 BC-AD 500: Equipment, Combat Skills and Tactics. - Moscow: Eksmo, 2007.