First Punic War

The Punic Wars were a series of three wars, with intervals, between Ancient Rome (the Roman Republic) and Carthage (a former Phoenician colony in North Africa that later became an independent state). Rome emerged victorious, seizing control of the entire Western Mediterranean and ultimately destroying Carthage.

The First Punic War was the first conflict between Rome and Carthage, lasting 23 years and ending in a Roman victory.

The term "Punic" comes from the Latin word punicus, referring to the Phoenicians living in North Africa, particularly the inhabitants of Carthage (a former Phoenician colony). The name also derives from their trade in a mollusk that produced a purple dye when processed.

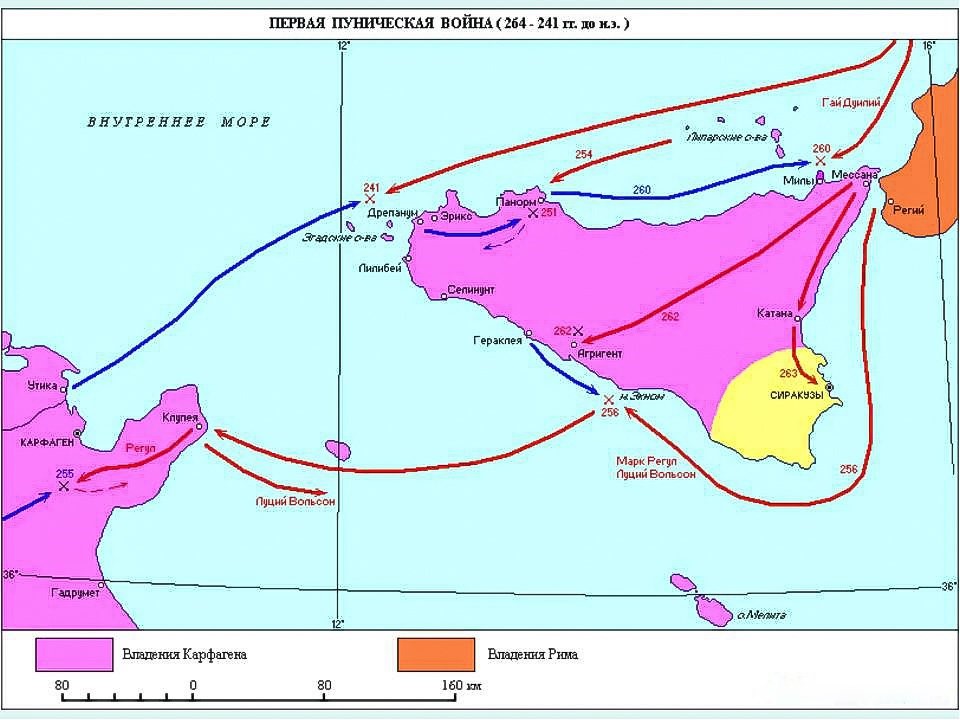

Military Campaigns of the First Punic War

Military Campaigns of the First Punic War

Balance of Power Before the War

For a long time, Rome and Carthage were allied, but after Rome's conquest of Italy, their interests clashed. Eventually, Rome's attempt to establish a presence in Sicily led to war. Sicily was not only a prosperous island but also a key strategic point, making its capture important for Rome.

The Roman invasion was prompted by mercenaries of King Agathocles of Syracuse—the Mamertines—who, after his death, were expelled from Syracuse and in 282 BCE took control of the northeastern part of the island. The new king, Hiero II, pushed them back after a difficult war, delivering a decisive defeat to 8,000 Mamertines at the Battle of Mylae with his army of 10,000 infantry and 1,500 cavalry. Facing a desperate situation, some Mamertines sought help from the Romans, while others turned to the Carthaginians. In Rome, the Senate referred the matter to the popular assembly, which decided to accept the Mamertines as Roman allies. This meant that the Mamertines became part of the Roman state, and under Roman law, Rome was obligated to defend them against all enemies.

This decision contradicted a treaty from 306 BCE, which stipulated that Rome could not have holdings in Sicily, and Carthage could not have any in Italy. However, the Romans justified their actions by claiming that Carthage had violated the treaty first during the final stage of the war with Pyrrhus when the Punic fleet entered the harbor of Tarentum.

At the start of this war, Rome had an experienced and strong army that had fought against King Pyrrhus (280–275 BCE), but at the time, the Roman navy was still weak. Rome had to strengthen its fleet during the course of the war. The Carthaginian army was smaller, but Carthage possessed a powerful navy with experienced sailors and admirals.

The reasons for the First Punic War from Carthage's perspective were to retain control of Sicily and to curb Rome's expansionist policies in the Mediterranean. From Rome's perspective, the goals were to seize Sicily and expand their territories and trade influence in the Mediterranean.

Armies At the beginning of the war, Rome did not have a navy but later built one from scratch. Rome's national army was composed of Roman citizens—legions and their allies. Carthage had war elephants, a strong military fleet, and a mercenary army at its disposal.

Carthaginian Commanders in the First Punic War: Hanno Hamilcar Barca (father of Hannibal and his brothers) Hiero (Tyrant of Syracuse, later sided with Rome) Bodas (Carthaginian admiral) Hasdrubal (son of Hanno) Bostar

Roman Commanders in the First Punic War: Appius Claudius Caudex Manius Valerius Maximus Corvinus Messalla Lucius Postumius Megellus Gaius Marcus Duilius Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Asina Marcus Atilius Regulus Lucius Cornelius Scipio Publius Claudius Pulcher Gaius Lutatius Catulus

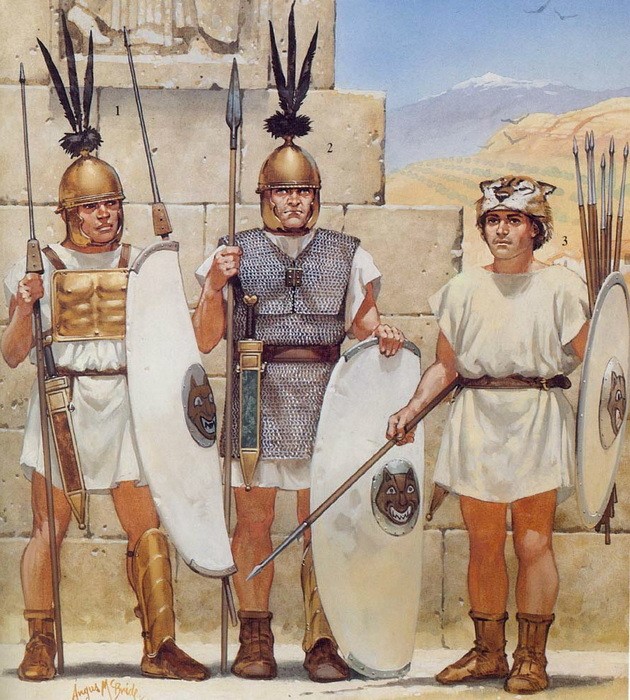

Roman Soldiers of the Punic Wars Era: Hastati or Principes, Triarii, Velites. Reconstruction by A. McBride

Roman Soldiers of the Punic Wars Era: Hastati or Principes, Triarii, Velites. Reconstruction by A. McBride

Course of the War

The war began due to Carthage's intervention in the Mamertines' struggle in Messana against the Syracusan tyrant Hiero II. Rome, having already brought the entire Apennine Peninsula under its control, sought to conquer the adjacent island of Sicily. Here, Rome's commercial interests clashed with those of Carthage. Fearing the expansion of Carthaginian influence and territories near Rome, Rome initiated military actions in Sicily.

In 264 BCE, Rome captured Messana. Following this, Rome formed an alliance against Carthage with Syracuse (a Greek colony on the eastern shore of Sicily) in 263 BCE. In 262 BCE, the Romans took Agrigentum. Understanding that Carthage was a maritime power and that only a decisive naval victory would allow them to conquer Sicily, Rome began building a navy. Until then, Rome had relied solely on its land-based armies—its legions.

In 260 BCE, Rome defeated Carthage in the naval Battle of Mylae, under the command of Consul Gaius Duilius. In the same year, the Romans secured another naval victory off Cape Ecnomus. Following this, land forces led by Marcus Regulus landed near Clupea in Africa in 256 BCE. Initially successful on land, the Romans were later defeated in the Battle of Carthage (modern-day Tunis) in 255 BCE. From 254 BCE onwards, the main military actions shifted to the western part of Sicily.

In 251 BCE, the Romans captured Panormus, but their attempts to take Lilybaeum (besieged in 250 BCE) and Drepanum were unsuccessful. These cities were only captured by the Romans in 242 BCE.

Under these circumstances, Carthage sent a new commander to its forces in Sicily—Hamilcar Barca. He managed to inflict several defeats on the Romans, but the defeat of the Carthaginian fleet in the Battle of the Aegates Islands in 241 BCE decided the war in Rome's favor.

In 241 BCE, a peace treaty was concluded, under which Carthage ceded its part of Sicily and the islands between Italy and Sicily to Rome, returned Roman prisoners without ransom, and paid a monetary indemnity of 3,200 talents of silver over ten years. Sicily became a Roman province.

Reconstruction of Carthage at the Start of the Punic Wars

Reconstruction of Carthage at the Start of the Punic Wars

The Last Battles of the War

The fighting resumed in Sicily as the Carthaginians recaptured Agrigentum and equipped a new fleet of 200 ships. The Romans also built a fleet of 220 ships. With their numerical superiority, the Romans began to press the Carthaginians hard in Sicily, recapturing Agrigentum and conquering Panormus (now Palermo). The Romans once again attempted to take the war to Africa, but the Carthaginian fleet forced the Roman ships onto a shoal, where a storm destroyed 150 ships. After these losses, the Senate decided to leave only a 60-ship fleet to defend the coast.

In 251 BCE, the Battle of Panormus took place. Consul Caecilius provoked the enemy into battle by initially feigning indecision. He kept his troops in Panormus and dug a large trench in front of his position. According to Polybius, the Roman light infantry harassed the enemy until Hasdrubal deployed his entire army (30,000 troops and 130 elephants). The Romans then retreated to the wall and the trench. Additionally, Caecilius deliberately placed few defenders on the walls to instill overconfidence in the Carthaginians. The Carthaginians approached the city, and the Romans bombarded the elephants. When the elephants attacked, the Romans took cover behind the trench. The elephants were then subjected to heavy missile fire from the walls and across the trench. Caecilius positioned himself behind the gates, facing the left flank of the Carthaginians, and continually sent reinforcements to his troops outside the city. Blacksmiths regularly brought out new weapons and placed them at the base of the wall. The elephants fled, disrupting the Carthaginian ranks. Fresh Roman forces emerged from the city, struck the flank, and achieved a complete victory. The attack was launched from all city gates, the Carthaginians were surrounded, and many tried to swim to their ships but drowned. The Romans offered freedom to the prisoners who captured the fleeing elephants, which Numidian prisoners agreed to do. A total of 120 elephants were captured, and the Carthaginians lost 20,000 men in this battle.

Encouraged by their success, the following year the Romans attempted to capture the Carthaginian stronghold of Lilybaeum (modern Marsala). A fleet of 200 ships and a 40,000-strong Roman army besieged it for a long time without success.

In 249 BCE, the Battle of Drepana (modern Trapani) took place. Consul Claudius had 120-210 ships. The Romans entered the harbor, hoping to surprise the enemy, but this failed. Carthaginian Admiral Adherbal managed to board his mercenaries and slip out of the harbor, sailing along the southern side of the city, which was located on a cape. He passed through the strait between the cape of Drepana and rocky islets and rounded the islands from the west. Part of the Roman fleet was in the bay, while others were approaching. As they attempted to leave the harbor, chaos ensued. Only part of the Roman ships managed to form a line facing west, with their backs to the shore. The Carthaginians, pressing the enemy against the shore, began their attack. Adherbal led the right flank, opposite Claudius. The maneuverability of the Carthaginian ships and the skill of their rowers allowed Adherbal to impose his tactics on the Romans. The Carthaginians outflanked and rammed enemy ships, driving them onto the shoals, and when the Romans attempted to board, they quickly withdrew to sea. Claudius, with 30 ships of the left flank, managed to break southward along the shore, but 93 to 137 Roman ships were captured by the Carthaginians, though the crews of the beached vessels escaped. Between 8,000 and 20,000 men were killed, and 20,000 to 50,000 were captured.

Soon, the remnants of the Roman fleet were destroyed in a new battle by the Carthaginian fleet and a storm, resulting in the loss of up to 150 ships.

The period from 248 to 242 BCE was marked by extreme exhaustion on both sides, but the initiative gradually shifted to Rome. In Sicily, Hamilcar replaced Cartalon as the new commander for Carthage. During this period, Hamilcar managed to repel Roman attacks on Lilybaeum and Drepana, launch a counterstrike near Panormus, and conduct several daring raids into the interior of Sicily and southern Italy. For his swift actions, he earned the nickname "Barca" (meaning "Lightning" in Phoenician). These successes gave the Carthaginians hope of winning the war, but subsequent actions were lackluster and achieved little.

In 242 BCE, Rome built a new fleet of 200 quinqueremes with private citizen funds. However, these ships were lighter than the usual Roman quinqueremes. The Romans were preparing for a decisive naval battle and no longer intended to rely solely on boarding tactics. Sailors and rowers trained daily. At the same time, the situation for the Carthaginians in Sicily became dire due to a shortage of provisions in Lilybaeum and Drepana. As a result, it was decided to send a fleet to assist the townspeople and Hamilcar Barca's Sicilian army. Hanno was placed in command of the fleet. The preparation of the Carthaginian fleet was not geared towards a naval battle with the Romans, so a significant portion of the ships were merchant transports, not intended for combat. Additionally, due to a lack of trained rowers, untrained individuals were assigned to the oars.

In 241 BCE, these fleets clashed at the Battle of the Aegates Islands. The Punic fleet of 250 ships was unable to withstand the Romans and was defeated, losing 50 ships sunk and 70 captured, while the Romans lost 30 ships sunk and 50 damaged. Carthage was eager to avenge this defeat, but it simply lacked the resources to continue the war. Moreover, after this defeat, the fate of Hamilcar Barca's army and the cities of Lilybaeum and Drepana hung in the balance due to the lack of payment for mercenaries and a severe food shortage.

The First Punic War

The First Punic War

Results

The Carthaginian government granted Hamilcar Barca extraordinary powers to negotiate peace. These negotiations concluded on terms that were relatively favorable for Carthage (the Roman assembly initially even refused to ratify them). According to the terms of the peace treaty, Carthage:

- Completely relinquished Sicily, which became a Roman possession.

- Agreed to pay an indemnity of 3,200 talents over 10 years.

- Paid a small ransom for its Sicilian army.

- The demand to surrender deserters and disarm the Sicilian army was rejected.

- Rome's victory was made possible by its superior resources—during the war, losses in ships amounted to 700 for Rome and 500 for Carthage.

The Roman army, originally composed of militia, had become experienced and relatively professional by the end of the war. In contrast, the Carthaginian army, composed mainly of mercenaries, often proved ineffective due to the lack of leadership skills among many Carthaginian commanders and their inability to manage a multilingual army. The mercenaries were also unreliable, prone to rebellion or desertion at the slightest delay in payment. Finally, Rome demonstrated its willingness to persevere and make any sacrifices necessary for victory. Carthage, which relied on mercenary armies, exhausted its reserves more quickly. Carthaginian citizens were less willing to make material sacrifices compared to the Romans. The inability to maintain large armies led to the impossibility of extensively employing boarding tactics at sea—this would have left the land front exposed. The fleet, therefore, employed ramming tactics, which required great skill from the crews.

In the interval between the First and Second Punic Wars, the Romans managed to seize Sardinia and Corsica from Carthage, taking advantage of Carthage's ongoing war with its rebellious mercenaries (240-238 BCE). After this conflict ended, Carthage attempted to reclaim Sardinia and Corsica, but Rome threatened war. Unprepared for a new conflict, Carthage chose to pay the Romans an additional 1,200 talents, in addition to the 3,200 talents of indemnity.

Carthage was able to offset the loss of Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica by establishing a number of colonies in Spain. Hamilcar and Hasdrubal managed to bring southern and eastern Spain under Carthaginian control. The wealth of Spain, particularly its silver mines, helped Carthage recover financially from the losses of the First Punic War and the war with the mercenaries. One of Carthage's major centers in Spain was the city of New Carthage (today’s Cartagena in Spain). Rome noticed Carthage's growing power in Spain and formed alliances with the Greek cities of Saguntum (today Sagunto in Spain) and Emporion in Spain, also demanding that the Carthaginians not cross the Ebro River (a river in the northeastern Iberian Peninsula).

Related topics

Roman Republic, Second Punic War, Third Punic War, Punic Wars

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Polybius. Universal History.

2. Titus Livy. Roman history from the founding of the city

3. Appian of Alexandria. Roman history

4. Plutarch. Comparative biographies

Contemporary authors:

1. Revyako K. K. Punic wars. Minsk: Universitetskoe Publ., 1988, 272 p. (in Russian)

2. Rodionov E. Punicheskie voyny [Punic Wars]. St. Petersburg: SPBU Publishing House, 2005. (Res militaris)

3. Bagnall, Nigel. The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. — London : Pimlico, 1999

4. Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201 // A Companion to the Punic Wars (неопр.) / Hoyos, Dexter. — Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011 г.

5. Shifman I. I. Carthage. Saint Petersburg: Saint Petersburg University Press. 2006

6. Delbrueck H. The history of military art in the framework of political history. — Translated from German-Vol. 1 "The Ancient world". - Moscow, 1936.

7. Eliseev M. B. The Second Punic War. - Moscow: Veche, 2018. - 480 p.: ill. - Series "Antique world".

8. Mashkin N. A. The last century of Punic Carthage / / VDI. - 1949. - No. 2.

9. Herbert William Park. Greek mercenaries. Dogs of War of ancient Greece / Translated from English by L. A. Igorevsky. - Moscow: ZAO "Tsentrpoligraf", 2013. - 288 p.

10. Warmington B.-H. Carthage. — L., 1960.

11. Mayak I. L. Sotsial'no-politicheskaya borba italiyskikh obshchestvov v period Gannibalovoy voyny [Socio-political struggle of Italian communities during the Hannibal War].

12. Shifman I. S. Vozrozhdenie karfagenskoi derzhavy [The Emergence of the Carthaginian Power].

13. Elnitsky L. A. The emergence and development of slavery in Rome in the VIII-III centuries BC-Moscow, 1964.