Second Punic War

The Punic Wars were a series of wars (there were three in total) with intervals between them, fought between Ancient Rome (Roman Republic) and and Carthage (a former Phoenician colony in North Africa that later became an independent state). Rome emerged victorious, capturing all of the Western Mediterranean and destroying Carthage.

The Second Punic War (also known by the Romans as the "War against Hannibal" or the Hannibalic War, 218-201 BC) was a military conflict between two coalitions led by Rome and Carthage for hegemony in the Mediterranean. At various times, Syracuse, Numidia, the Aetolian League, and Pergamum fought on the side of Rome, while Macedonia, Numidia, Syracuse, and the Achaean League sided with Carthage.

The Punics or Poeni (Latin: punicus) was the Latin name for the Phoenicians living in North Africa, primarily the inhabitants of Carthage (a former Phoenician colony). They were also called this because they traded in mollusks, which produced a purple dye when processed.

Military campaigns of the Second Punic War

Military campaigns of the Second Punic War

Power Balance Before the War

The peace of 242 BC was bought at a high price. The Romans not only acquired all the revenues that the Carthaginians received from Sicily, but also significantly weakened Carthage's almost monopolistic trade dominance in the West. Rome's behavior during the Mercenary War clearly showed its hostile stance—it became evident that peaceful coexistence was absolutely impossible.

The most important political act of the general Hasdrubal, which furthered Hamilcar's initiatives more than his other actions, was the founding of New Carthage on the Mediterranean coast of the Iberian Peninsula. This city, located on the shore of a convenient bay and surrounded by a chain of impregnable hills, was more fortunate than Akra Leuke: while the latter, as far as can be judged, always remained a backwater town and was unable to compete with Gades, New Carthage immediately became the administrative center of the Punic holdings in Spain and one of the most important trading centers in the entire Western Mediterranean. Through the efforts of these people, Carthage not only fully compensated for the losses incurred during the First Punic War but also acquired new markets, and the silver mines brought in such revenues that Hamilcar's and Hasdrubal's political opponents were completely deprived of the opportunity to oppose them. The actions of the Barcids naturally caused concern among the Greek colonies on the Iberian Peninsula. They felt a threat to their independence and turned to Rome for protection, giving Rome a desired pretext to intervene in Spanish affairs. Even during Hamilcar's lifetime, negotiations took place between Rome and Carthage, and their spheres of influence were divided (the southern part being Punic and the northern part Roman), with the Ebro River recognized as their boundary.

At the time of his father's death, Hannibal was seventeen years old. Judging by subsequent events, he, along with his brothers Mago and Hasdrubal, left Spain and returned to Carthage. The environment of the military camp, participation in campaigns, and observations of his father’s and brother-in-law’s diplomatic activities undoubtedly had a decisive impact on his formation as a military leader and statesman.

Hannibal owed his exceptional education, including his knowledge of the Greek language and literature and the ability to write in Greek, to his father. The significance of Hamilcar Barca's step in acquainting his children with Hellenistic culture is evident, as it was made despite an old law that prohibited learning Greek. By overriding this long-standing regulation, which was meant to isolate the Punics from their traditional enemy, Syracuse, but effectively isolated them from the surrounding world, Hamilcar aimed not only to prepare his children, especially Hannibal, for active political activity in the future. He also wanted to emphasize his desire to integrate Carthage into the Hellenistic world—not as a foreign element but as an organic part—and to secure Greek support and sympathy in the upcoming struggle against the Roman "barbarians." Meanwhile, Rome began to take an interest in Western Mediterranean affairs and formed an alliance with Saguntum, directly aimed against Carthage, intending to halt its northward expansion.

Hannibal returned to Spain, where, thanks to his personal qualities, he became very popular in the army. After Hasdrubal's death, the soldiers elected him as their commander-in-chief.

When Hannibal came to power, he was twenty-five years old. Carthaginian dominance in Spain was firmly established, and the southern part of the Iberian Peninsula seemed like a reliable springboard for an offensive against Rome. Hannibal himself had already established the traditional strong ties of the Barcids with the Iberian world: he was married to an Iberian woman from the allied city of Castulo. He immediately behaved as if the war with Rome was already decided and entrusted to him, with Italy as his designated theater of operations. Hannibal, apparently, did not conceal his intention to attack Rome's ally Saguntum and thus draw Rome into direct conflict. However, he sought to make it appear that the attack on Saguntum would occur naturally as a result of the unfolding events. To this end, he won several victories over the Spanish tribes living on the northern borders of Carthaginian territories and approached the boundaries of Saguntum's territory. Despite Saguntum being a Roman ally, Hannibal could count on Rome's non-interference, as it was preoccupied with the struggle against the Gauls and Illyrian pirates. By provoking conflicts between Saguntum and the Iberian tribes under Punic control, he intervened in the conflict and, under a minor pretext, declared war. After a rather tough seven-month siege, the city was taken, and Rome did not dare to provide Saguntum with military assistance, merely sending an embassy to Carthage after the city's capture to directly declare the start of the war. Before marching to Italy, Hannibal gave his army a winter rest. He paid serious attention to the defense of Africa and Spain. In Africa, Hannibal left 13,750 infantry and 1,200 cavalry recruited in Spain, and sent 870 Balearic slingers there. Carthage itself was additionally reinforced with a 4,000-strong garrison. Hannibal appointed his brother Hasdrubal to command the Punic forces in Spain and handed over significant military forces to him: 11,850 Libyan infantry, 300 Ligurians, 500 Balearics, and 450 Libyo-Phoenician and Libyan cavalry, 300 Ilergetes, and 800 Numidians. Additionally, Hasdrubal had 21 elephants and a fleet consisting of 50 penteres, 2 tetreres, and 5 trieres to defend the coast against Roman sea invasions.

The invasion army consisted of approximately 50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, and 37 elephants. Meanwhile, the Romans were also preparing for war. Consul Tiberius Sempronius Longus had 24,000 infantry, 2,400 cavalry, and 160 ships. The second consul, Publius Cornelius Scipio, had 22,000 infantry and 2,200 cavalry. The Roman army in Gaul, under the command of Praetor Lucius Manlius, numbered 18,000 infantry and 1,600 cavalry. In total, the Roman army had 64,000 infantry and 6,200 cavalry—slightly more than Hannibal's. The significant advantage for the Romans was that they were to fight on their home territory, and for them, mobilizing additional military contingents was easier than for the Punic general to receive reinforcements. However, the Roman army's dispersion and lack of unified command complicated the Romans' conduct of military operations. Fortunately for Carthage, Hannibal was a military genius.

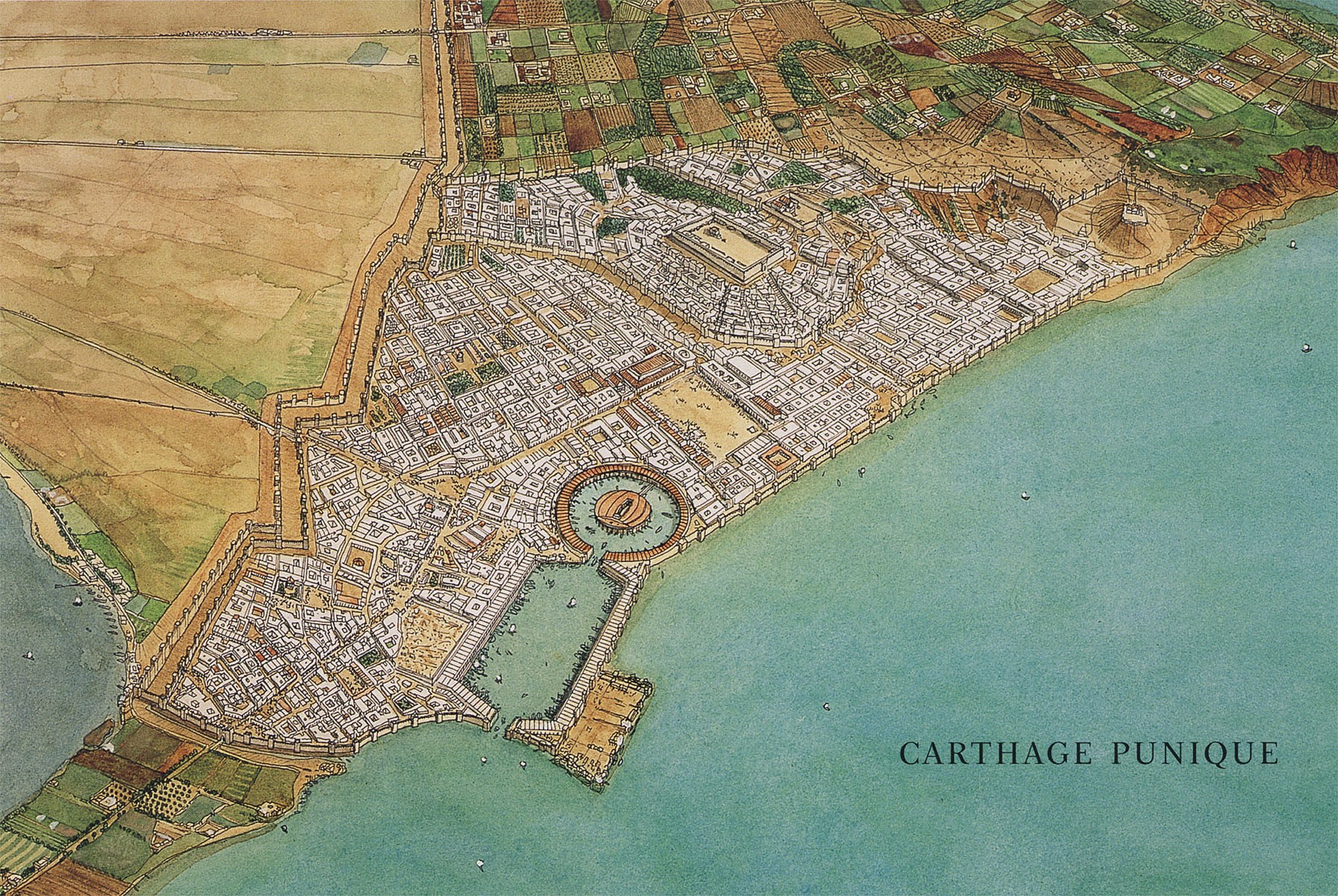

Reconstruction of Carthage at the Beginning of the Punic Wars

Reconstruction of Carthage at the Beginning of the Punic Wars

Reasons From Carthage's perspective: Establishing dominance in the Mediterranean and the struggle for control over Spain. From Rome's perspective: Establishing dominance in the Mediterranean and eliminating Carthage's foothold in Spain.

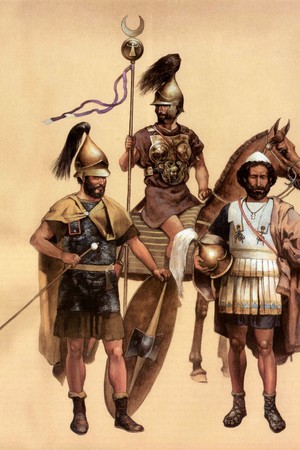

Armies: At the start of the wars, Rome had no navy, which it later built from scratch. The Roman national army comprised Roman citizens (legions) and their allies. Carthage had war elephants, a strong navy, and a mercenary army.

Carthaginian Commanders in the Second Punic War

- Hannibal Barca

- Hasdrubal Barca

- Mago Barca

- Hasdrubal Gisco

- Maharbal

- Hanno the Elder

- Hanno (son of Bomilcar)

- Himilco (naval commander)

- Syphax (ruler of Western Numidia from the middle of the war)

- Masinissa (ruler of Eastern Numidia, later switched to Rome)

- Philip V of Macedon (King of Macedonia)

- Philopoemen (strategist of the Achaean League)

Roman Commanders in the Punic War

- Quintus Fulvius Flaccus

- Gnaeus Centumalus Fulvius

- Gaius Terentius Varro

- Appius Claudius Pulcher

- Publius Cornelius Scipio

- Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio Calvus

- Tiberius Sempronius Longus

- Gaius Flaminius

- Gnaeus Servilius Geminus

- Marcus Atilius Regulus

- Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator

- Marcus Minucius Rufus

- Lucius Aemilius Paullus

- Marcus Claudius Marcellus

- Gaius Claudius Nero

- Marcus Livius Salinator

- Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus

Rome's Allies

- Masinissa (ruler of Eastern Numidia, later the first king of unified Numidia after the war, initially sided with Carthage)

- Syphax (King of Western Numidia, later switched to Carthage)

- Machanidas (tyrant of Sparta)

Bust of Hannibal, National Museum of Naples

Bust of Hannibal, National Museum of Naples

Course of the war

Understanding that a new war between Rome and Carthage was inevitable, both sides sought allies. Rome's allies at various times included Syracuse, Numidia (a state in North Africa), and the Aetolian League (a union of cities in central Greece). Carthage's allies included Macedonia, Numidia, Syracuse, and the Achaean League (a military-political union of cities in ancient Greece on the Peloponnesian Peninsula).

The war was sparked in 219 BCE by Hannibal's capture of the Roman-allied city of Saguntum in Spain. A Roman embassy sent to Carthage demanded Hannibal's surrender. The Carthaginian refusal was used by Rome as a pretext for war. Rome, preparing for the new war, planned to conduct it in Carthage's territories in Spain and Africa. Hannibal, however, planned to conduct the war on Roman territories, including Italy and recently conquered lands of the Gauls (Cisalpine Gaul). Hannibal also counted on the support of Rome's Italian allies, who were discontent with its rule.

In Spain, Hannibal left an army of 15,000 under his brother Hasdrubal's command and, with the remaining forces (50,000 infantry, 9,000 cavalry, and several war elephants), moved through the Pyrenees towards the Alps, intending to cross them and invade Italy. The Alpine crossing from Spain to Cisalpine Gaul was extremely difficult, causing Hannibal to lose nearly all his war elephants and half his army. Hannibal himself lost an eye during the crossing.

Early in the war, Hannibal achieved several victories over Roman armies: the Battle of Ticinus (defeating Publius Scipio's army) and the Battle of Trebia (defeating Tiberius Sempronius' army) in 218 BCE. These successes replenished Hannibal's depleted army with Celtic and Ligurian tribes.

In 217 BCE, Hannibal again defeated the Romans under consul Gaius Flaminius at the Battle of Lake Trasimene. After this, Hannibal moved east, but his expectation that Rome's Italian allies would defect to his side did not materialize; most allies remained loyal to Rome. He then ravaged the southern regions of Italy. Meanwhile, Rome, facing severe losses, appointed a dictator, Quintus Fabius Maximus, who avoided decisive battles with Hannibal, focusing on disrupting his supply lines. This strategy earned Fabius the nickname "Cunctator" ("The Delayer"). However, the Senate, dissatisfied with Fabius' actions, soon recalled him. After wintering near the town of Geronium, in the spring of 216 BCE, Hannibal moved to Apulia. There, on August 2, 216 BCE, the Battle of Cannae took place. Despite being outnumbered, Hannibal decisively defeated and annihilated the superior Roman forces. Rome fielded about 80,000 troops, while Hannibal had about 40,000. The battle resulted in the deaths of both Roman consuls, Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro. This victory finally led many tribes and city-allies (such as Capua) to defect to Hannibal's side, as he had hoped at the war's outset.

From 215 BCE onwards, Rome had to fight not only Hannibal in Italy but also his allies—Macedonia (Greece) and Syracuse (Sicily). After the defeat at Cannae, the Romans returned to the strategy of a protracted war against Hannibal, initially implemented by Fabius Maximus, aiming to exhaust the enemy. This strategy proved effective, as Carthage, fearing Hannibal's growing power, nearly ceased sending him money and reinforcements. Rome also began conducting wars in Sicily and Spain to further weaken Hannibal's Italian army.

In the spring of 217 BCE, a naval battle at the Ebro River (north-east Spain) occurred between the Roman and Carthaginian fleets. The Carthaginian fleet was commanded by Himilco, and the Roman fleet by Gnaeus Cornelius Scipio. Rome emerged victorious, securing control over the Spanish coastal waters.

In 212 BCE, Marcus Marcellus took Syracuse, then Agrigentum, and by 210 BCE, Rome had restored its control over all of Sicily. In Italy, from 214-213 BCE, military actions were fought with varying success.

In 212 BCE, Hannibal managed to capture Tarentum, except for the citadel, which remained in Roman hands. After this, the Romans besieged Capua. Hannibal's attempts to rescue it were unsuccessful, and eventually, the city was taken by the Romans in 211 BCE. Meanwhile, Carthage's ally, King Gala of Eastern Numidia, with his son Masinissa, managed to take out Rome's ally in Africa, King Syphax of Western Numidia.

This allowed Carthage to concentrate three armies in Spain under the command of Hasdrubal (Hannibal's brother), Hasdrubal, son of Gisco, and Mago. Seeing that the Roman forces were divided and taking advantage of the local Spanish betrayal to the Romans, they managed to individually defeat the Roman armies in Spain in 212 BCE, commanded by Publius and Gnaeus Scipio, who perished in these battles.

In 209 BCE, Quintus Fabius Maximus captured Tarentum. In the same year, a new Roman commander, Publius Cornelius Scipio (Scipio Africanus the Elder), arrived in Spain and managed to capture Carthage's main stronghold in Spain, the city of New Carthage.

In the spring of 208 BCE, the Battle of Baecula (modern-day Bailén in Spain) took place between Hasdrubal and Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus the Elder. Scipio emerged victorious. However, Hasdrubal, with a large part of his army, managed to break through to his brother in Italy. As a result, local Spanish Iberian tribes began to side with Rome. Hasdrubal couldn't join his brother in Italy because he was defeated and killed in the Battle of the Metaurus (modern-day Metauro River in Italy) in Northern Italy in 207 BCE. The Roman forces in this battle were commanded by Consul Gaius Claudius Nero. Consequently, Hannibal's position became very difficult, as Rome was able to regain control of Sicily, Sardinia, and Spain. Additionally, Macedonia was forced to make peace with Rome.

All this allowed Scipio Africanus, with Senate permission, to prepare an army (in 205 BCE) and land in Africa, northwest of Carthage, near the city of Utica in 204 BCE. Scipio had long dreamed of this. Shortly after landing, he defeated the forces of King Syphax of Western Numidia, who had betrayed Rome. The Carthaginians attempted to initiate peace negotiations, but they led nowhere. Then, in 203 BCE, the rulers of Carthage recalled Hannibal from Italy to defend the city. Hannibal led a poorly trained militia and remnants of mercenary troops.

In 202 BCE, the final Battle of Zama occurred, which Hannibal lost. The Romans in this battle were commanded by Scipio Africanus.

Results

In 201 BCE, a peace treaty was concluded, under the terms of which Carthage renounced its territories in Spain and the Mediterranean islands, destroyed its military fleet, agreed not to wage wars outside Africa, and in Africa only with Rome's permission. Additionally, the Carthaginians were to pay an annual tribute of 200 talents for 50 years. Thus ended the Second Punic War.

Due to the defeat in the war and Roman demands for Carthage to hand him over, Hannibal was forced to flee Carthage. He eventually settled in Bithynia, where he chose suicide over being handed over to the Romans.

Between the Second and Third Punic Wars, Carthage tried to avoid conflicts with Rome, dreaming of revenge and gradually recovering through trade. During this period (from 201 to 149 BCE), Rome managed to subdue all of Greece, including Macedonia, and conquer Syria.

Seeing the Carthaginian merchants as trade competitors and fearing Carthage's recovery, Rome began preparing for a new and decisive war with Carthage. Senator and former envoy to Carthage, Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder (Marcus Porcius Censor), especially called for a new war and the destruction of Carthage.

Bust of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. 1st century CE. Bronze. Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Bust of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus. 1st century CE. Bronze. Naples, National Archaeological Museum

Related topics

Roman Republic, First Punic War, Third Punic War, Carthage

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Polybius. Universal History.

2. Titus Livy. Roman history from the founding of the city

3. Appian of Alexandria. Roman history

4. Plutarch. Comparative biographies

Contemporary authors:

1. Revyako K. K. Punic wars. Minsk: Universitetskoe Publ., 1988, 272 p. (in Russian)

2. Rodionov E. Punicheskie voyny [Punic Wars]. St. Petersburg: SPBU Publishing House, 2005. (Res militaris)

3. Bagnall, Nigel. The Punic Wars: Rome, Carthage and the Struggle for the Mediterranean. — London : Pimlico, 1999

4. Punic Politics, Economy, and Alliances, 218–201 // A Companion to the Punic Wars (неопр.) / Hoyos, Dexter. — Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011 г.

5. Shifman I. I. Carthage. Saint Petersburg: Saint Petersburg University Press. 2006

6. Delbrueck H. The history of military art in the framework of political history. — Translated from German-Vol. 1 "The Ancient world". - Moscow, 1936.

7. Eliseev M. B. The Second Punic War. - Moscow: Veche, 2018. - 480 p.: ill. - Series "Antique world".

8. Mashkin N. A. The last century of Punic Carthage / / VDI. - 1949. - No. 2.

9. Herbert William Park. Greek mercenaries. Dogs of War of ancient Greece / Translated from English by L. A. Igorevsky. - Moscow: ZAO "Tsentrpoligraf", 2013. - 288 p.

10. Warmington B.-H. Carthage. — L., 1960.

11. Mayak I. L. Sotsial'no-politicheskaya borba italiyskikh obshchestvov v period Gannibalovoy voyny [Socio-political struggle of Italian communities during the Hannibal War].

12. Shifman I. S. Vozrozhdenie karfagenskoi derzhavy [The Emergence of the Carthaginian Power].

13. Elnitsky L. A. The emergence and development of slavery in Rome in the VIII-III centuries BC-Moscow, 1964.