Architecture in Ancient Rome

Roman art represents the highest achievement and culmination of ancient art, and architecture is one of its aspects. Roman architectural works include buildings, ensembles, as well as structures that organize open spaces (monuments, bridges, embankments, etc.). The planning and construction of cities and settlements constitute a special area of architectural art called urban planning. It encompasses the construction of official buildings (palaces, theaters) as well as utilitarian structures that serve the life of the city (bridges, roads, streets). Roman architecture is a splendid example of the symbiosis of the architectural achievements of Italian tribes and Greek culture. However, this symbiosis was not a blind imitation. The Romans were able to borrow the most innovative aspects from these cultures and adapt them to their own realities and mentality.

Particular attention is deserved by the following architectural structures in Rome:

Originally, the architecture of ancient Rome developed on the basis of the culture of the Etruscans, who inhabited the Apennine Peninsula in the 2nd-1st millennium BCE. Having conquered the Etruscans in the 3rd century BCE, the Romans adopted their achievements in architecture, sculpture, and painting. The unique technical techniques of the Etruscans laid the foundation for Roman engineering. The constructive principles that emerged in the architecture of the Early Republic largely trace their origins to Etruscan systems. In temple architecture, the Romans adopted the high podium, steep multi-step staircase at the entrance, and the solid rear side of the building from the Etruscans. There is a noticeable repetition of Etruscan forms in Roman tombs. The constructions of the tomb of Cecilia Metella and the Mausoleum of Augustus derive from Etruscan tumuli, and later, the tomb of Hadrian (G. I. Sokolov, Art of the Etruscans, Moscow, 1990).

Roman architecture, under the influence of the Etruscans, perfected the system of arches as a method of construction (vaulting), the origins of which can be traced back to the Ancient East and Greece (Kovalyov S.I. History of Rome). The Romans particularly followed the Etruscans in the construction of roads, bridges, and defensive walls.

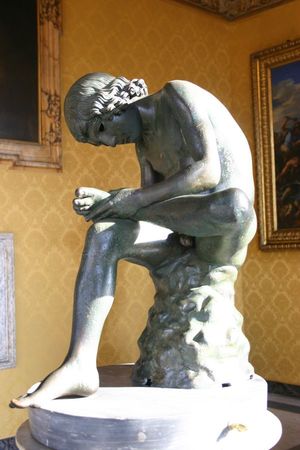

Etruscan sculpture exerted an influence on the Romans no less significant than architecture. Already in the early years of the Republic, the Roman monument - the Capitoline Wolf - was created by an Etruscan master, possibly Vulca. The influence of Etruscan masters on the formation of Roman portraiture, especially in bronze casting, should not be underestimated. The specificity of Etruscan artistic thinking, their love for precision and details, resonated with the Roman way of perceiving reality.

Etruscans did not have a strong affinity for mosaic art, but their highly developed multicolored paintings in tombs sparked the interest of the Romans in wall painting. While wall painting was not highly developed among the Greeks from the 7th to 4th centuries BCE due to their overall plastic, rather than illusionistic-pictorial, system of artistic worldview, the Etruscans widely embraced it. This greatly influenced the development of Roman frescoes and gave rise to a new practice of perceiving the world that was not purely plastic but illusionistic-pictorial, eventually becoming dominant in Europe (Sokolov G.I. Art of the Etruscans). In this regard, the Etruscans predetermined many characteristics not only of Roman art but also of European art in general.

However, it was not the Etruscan cultural influence that played the leading role in the development of Roman architecture. Starting from the 3rd century BCE, Rome engaged in military actions on the Balkan Peninsula, which culminated in the conquest of Athens by Sulla in 86 BCE. After this event, Rome became immersed in the circle of Hellenistic culture, which had a much greater influence on the early period of Roman architecture than Etruscan culture did (Brunov N.I. Essays on the History of Architecture). Greece found itself under Roman territorial and political control, but Rome itself fell captive to Greek culture. Greek mythology, poetry, the heroic image of man, plastic forms of expression, and the system of orders enriched Roman art, and on Roman soil, ancient art experienced a new and final flourishing (Kobyilina M.M. Art of Ancient Rome). Interestingly, at the initial stage of the conquest of Greece, the Romans' fascination with Greek culture was not significant; it primarily involved plundering the country for trophies: Roman legionnaires would take everything they could carry on their ships. Many of these works of art would later adorn Roman temples and squares. However, in the future, the Romans demonstrated receptivity and the ability to become knowledgeable students. They adeptly assimilated technical and formal achievements, primarily from the visually striking world of Greek forms (Hartmann K.O. History of Architecture, Vol. 1). Over time, the value of Greek treasures increased, making them accessible only to the upper class. Noble Romans purchased Greek statues to decorate their countryside villas. Greeks engaged in various professions, including a large number of sculptors and copyists, settled in Rome and always had numerous commissions. The study of Greek architecture by Roman sculptors and architects began.

From everything mentioned above, it is evident that the Romans borrowed much from Greek culture, but the Roman mentality was different, more pragmatic, than the poetic mentality of the Hellenes. Roman constructions of the considered period sharply display Italian characteristics - greater severity and insularity (Blavatsky V.D. Architecture of Ancient Rome). In Rome, from the beginning of the Republican period, the predominant forms of art were those with practical purposes. Such types of structures included roads, bridges, and aqueducts. Monumental and luxurious buildings appeared in Rome later. Among them were structures embodying the power of the Roman state and later the emperors, catering to the needs of the slave-owning elite and aiming to gain popularity among the free urban population: forums, triumphal arches, amphitheaters, baths, basilicas, palaces and villas, engineering structures serving the cities of the Roman Empire, and above all, the giant center of the metropolis, the city of Rome (General History of Art, Vol. 1. Art of the Ancient World/Ed. by Chegodayev A.V.).

Related topics

Literature

1. Blavatsky V. D. Architecture of ancient Rome.М,1938

2. Brunov N. I. Essays on the history of architecture. Moscow, 1935

3. General History of Art, Vol. 1. Art of the Ancient World/Ed. by Chegodayev A.V. Moscow, 1956.

4. Hartman K. O. Istoriya Arkhitektury [History Of Architecture].T1. M, 1936

5. Kobylina M. M. Iskusstvo drevnego Rima [The Art of ancient Rome]. Moscow, 1939

6. Kovalev S. I. Istoriya Rima [History of Rome], St. Petersburg, 2006

7. Sokolov G. I. Iskusstvo etruskov [The Art of the Etruscans], Moscow, 1990

Gallery

Gallery