Reign of the Antonine Dynasty

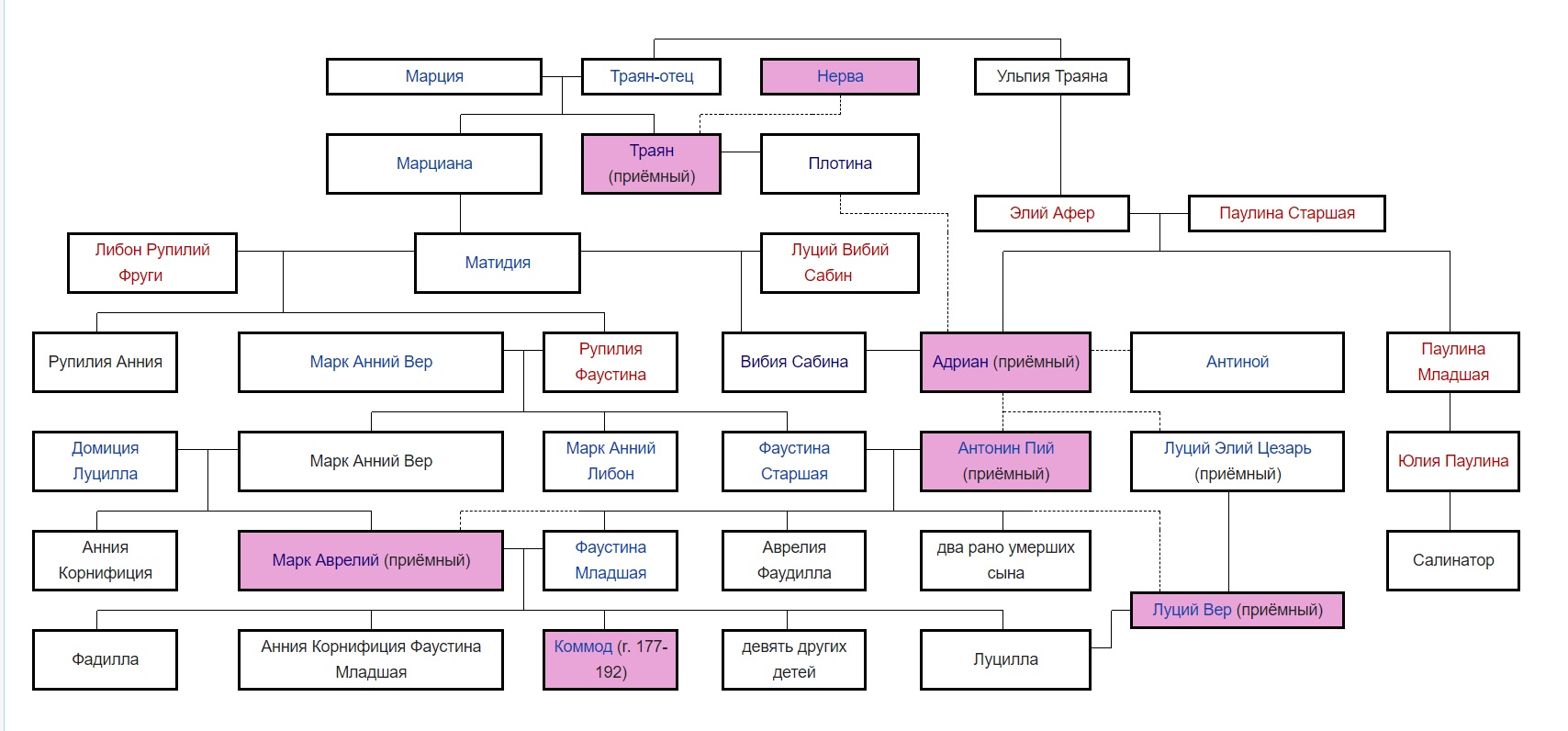

The Antonines (Lat. Antonini, in honor of Antoninus Pius) are the third dynasty from the beginning of the principate of the Roman Empire, which ruled from 96 to 192 AD.

The first representative was Marcus Cocceius Nerva, with all subsequent members, excluding him, originating from the provincial nobility. The distinctive features of the Antonines were their excellent relationship with the Senate during the hereditary power (usually through adoption; only Commodus was the natural son of his predecessor, and his rule turned out to be disastrous) often with the presence of co-rulers. The first five representatives of the dynasty because of this unofficially came to be known as the "good emperors".

- Nerva

- Antoninus Pius

- Marcus Aurelius, co-emperor Lucius Verus

- Commodus

By the time of the Flavians, the principate had ceased to be a contradictory, republican-monarchical system, so the autocratic nature of the Antonines' power was not in doubt. The old Roman aristocracy, which once forced Octavian Augustus to establish a partnership with them, had long left the historical scene. The Roman Senate now sat nobles from various regions of the Mediterranean, both western and eastern. This Senate had completely lost its republican illusions, and all its demands were reduced to one thing: not to execute senators without the permission of the Senate itself. The vow to observe this condition, given by Emperor Nerva, was broken only by Commodus.

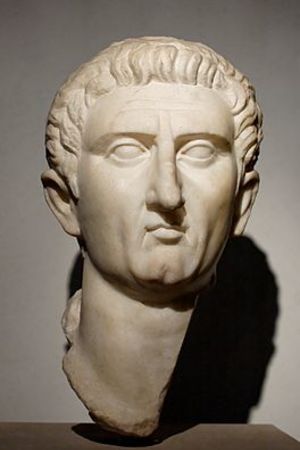

Nerva

After coming to power, Marcus Cocceius was officially named Emperor Nerva Caesar Augustus; less often - Emperor Caesar Nerva Augustus. In 97 AD, he adopted the honorary nickname Germanicus and was proclaimed emperor in the original sense of this term, so his full title became Imp. Nerva Caesar Aug., Germanicus, pontifex maximus, tribuniciae potestatis II, imp. II, cos. IV, pater patriae. One inscription calls him by his original prenomen and nomen (Marcus Cocceius), but this is a clear anomaly. Another inscription names Nerva proconsul, but this is also a mistake: the emperor did not assign this position, as he never had to leave Italy during his reign. Ancient authors usually call him simply Nerva, sometimes - Cocceius Nerva or divine Nerva.

The Senate's proclamation of Nerva could directly result in the growth of the authority of this power organ. The new emperor solemnly swore that during his reign no senator would be put to death, and he kept his word; besides, he did not make important decisions without first discussing them in the Senate. Coin minting began with the inscription Providencia senatus ("by the will of the Senate"). Nerva announced the termination of lawsuits for the insult of the emperor's majesty and treason, very common under Domitian, released all those suspected of this crime from detention, and pardoned the convicted. All property unlawfully confiscated under his predecessor was returned to the owners.

Despite the populist measures taken by Nerva, his regime was still unstable. The main reason for this was the lack of support from the army and the Praetorian Guard, who remembered Domitian kindly. Immediately after the change of power, unrest began in the provincial armies. Thus, Pliny the Younger mentions the preparation for a rebellion of some commander of a "large and glorious army" in the East (this could be the governor of Syria or Cappadocia). This threat was dealt with, but it is not known exactly how. An open rebellion broke out in the Danubian legions; presumably, it was Dion Chrysostom who managed to stop it with his intervention.

There was also unrest in Rome. Gaius Calpurnius Piso Crassus Frugi Licinian (the adoptive brother of Galba's son) early in 97 AD, conspired and began to incite soldiers to rebellion, promising them generous handouts in case of his rise to power. This conspiracy was timely uncovered, and sources report Nerva's very soft reaction: observing the oath given at the beginning of his rule, he merely exiled Crassus with his wife, Agedia Quintina, to Taranto, although "the senators reproached him for his indulgence".

The rebellion of the Praetorian Guard proved to be more dangerous. Under Domitian, it regained its independence after a certain break, so it was harder for the guards than for the soldiers of the provincial armies to reconcile with the impunity of the emperor's killers. In addition, one of the two praetorian prefects involved in the conspiracy, Titus Flavius Norbanus, died, and Nerva made an unfortunate staffing decision: he appointed Casperius Aelianus, who had already held this position under Domitian (in 84-94 AD), to his place. Aelianus used his high position to raise an open rebellion: in the autumn of 97 AD, the Praetorians led by him besieged the imperial palace and essentially took Nerva hostage. This was not a coup, but an attempt to pressure the emperor: the guards demanded the murderers of Domitian to be handed over for execution. According to Dion Cassius, "Nerva opposed them so decisively that he even bared his clavicle and exposed his throat." Pseudo-Aurelius Victor writes that the emperor during these events "was so frightened that he could not hold back vomiting and bowel movements, but still resisted strongly, saying that it would be better for him to die than to undermine the authority of power by handing over those who helped him achieve it." But he still had to hand over these people, Titus Petronius Secundus and Domitian's former chamberlain Parthenius. The Praetorians struck Petronius with one blow, and Parthenius "first had his genitals cut off, thrown in his face [and] then he was strangled." After this, Nerva had to deliver a speech to the people in which he thanked the Praetorians for this execution.

Now it became obvious that Nerva did not have enough strength to hold power and maintain stability within the empire; the lack of an official successor made the emperor especially vulnerable given that Nerva was old and not in good health. Marcus Cocceius needed such a successor who would be loyal to both the people and the army. Therefore, he rejected the candidacies of his relatives and decided to make one of the prominent military leaders his successor. Perhaps for some time he considered suitable for this role the governor of Syria Marcus Cornelius Nigrinus Curiatius Maternus, but in the end, Marcus Ulpius Trajan, who ruled Upper Germany, was chosen.

Decisive factors in this choice could have been Trajan's popularity in the army and his connections. Marcus Ulpius made a career "from the bottom", from a simple legionnaire, and was a capable military leader, so the soldiers loved him. He commanded one of the strongest military groups of the empire, the Upper German legions, and his closest friend Lucius Licinius Sura was the governor of Lower Germany with its three legions. Another friend of Trajan, Quintus Glitius Agricola, ruled Upper Moesia, and under his command were another three legions; finally, Trajan had close relations with the governors of Syria and Cappadocia, and presumably with the governors of Lower Moesia and Britain. Thus, the adoption of Marcus Ulpius guaranteed Nerva the loyalty of most of the key provinces with their border armies. Finally, Trajan was relatively young and full of strength.

Nerva ignored the provincial origin of Trajan, who was a native of Baetica, "for he believed that one should look at the valor of a man, not his place of birth". Shortly after the Praetorian rebellion, in September 97 AD, the emperor announced the adoption of Trajan under the name of Nerva Caesar. On October 25, a formal adoption procedure was carried out, after which Marcus Ulpius received the title of Caesar, the consulate for the year 98 (jointly with Nerva), the powers of a people's tribune, and proconsular power over all of Roman Germany, thus becoming Nerva's de facto co-ruler. Dion Cassius writes that, informing Trajan of all this, the emperor sent him a letter with a line from the "Iliad" "Avenge my tears with your arrows, Argives!". Some researchers admit that this could be a fictional episode.

Marcus Ulpius Trajan

Emperor Marcus Ulpius Trajan (98–117) was originally from Spain. The Senate under him, as well as under the next princes of the 2nd century, consisted largely of provincial nobility and expressed the interests of the slave-owning class of the entire empire. This served as a social basis for the agreement between the emperors of the Antonine dynasty and the Senate, which was broken only by the very last representative of this dynasty, Commodus, at the end of the 2nd century.

Under Trajan, Rome made its last major conquest: Dacia was conquered in 101-106 AD. This fertile country, rich in various natural resources, proved to be a very valuable province for Rome. Many Roman citizens from Italy moved here, and many colonies of veterans were founded. The influx of Roman population for permanent residence in Dacia contributed to the intensive Romanization of this province. To this day, the inhabitants of this country, modern Romania, speak a Romance language, a descendant of Vulgar Latin.

Trajan also fought with Parthia, a powerful eastern neighbor of Rome. He managed to capture all of Mesopotamia for some time, where Roman provinces were created. But due to the resistance of the local population and the opposition of Parthia, the Romans failed to retain these conquests. Soon after Trajan's death, Rome had to give up Mesopotamia.

Publius Aelius Hadrian

Trajan's successor was Publius Aelius Hadrian (117–138). He was a well-rounded, educated individual. A lover of travel, he toured almost the entire Roman Empire in the 20 years of his reign, studying provincial life and overseeing conditions in them.

Under Hadrian, the creation of the imperial bureaucratic apparatus was completed. This made it possible to abolish the contract system for the collection of all taxes in the provinces. State service became honorable and well paid. A state postal service was created to strengthen Rome's ties with the provinces. Under Hadrian, the provincialization of the Roman army began: it began to accept Roman citizens living not only in Italy but also in the provinces.

In 132-135 AD, a new rebellion took place in Judea, led by Bar Kokhba, which was suppressed with great cruelty. Up to half a million people perished. On the site of Jerusalem, Hadrian founded a Roman colony, and many of the remaining Jews in Palestine were evicted.

In foreign policy, Hadrian's time represented a transition from conquest to defense. The Romans lost Mesopotamia, and the Euphrates once again became the border with Parthia. The borders along the Rhine and the Danube are greatly strengthened. In Britain, the massive Hadrian's Wall was created, stretching from sea to sea and designed to protect against northern tribes.

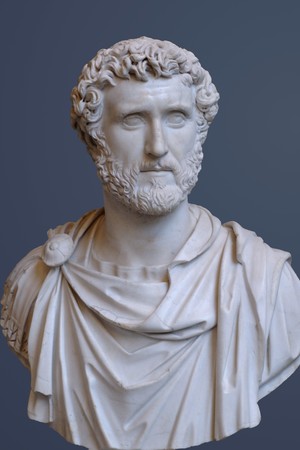

The slave-owning elite of the empire considered Antoninus (138–161) the ideal monarch and gave him the nickname Pius ("pious"). Under Antoninus, complete agreement was established between the emperor and the Senate; the Senate was returned control of Italy. Antoninus paid great attention to the protection of the borders and maintaining peace with neighbors. Defensive structures, the so-called Antonine walls, were hastily built along the borders.

Antoninus Pius

The slave-owning elite of the empire considered Antoninus (138–161) the ideal monarch and gave him the nickname Pius ("pious"). Under Antoninus, complete agreement was established between the emperor and the Senate; the Senate was returned control of Italy. Antoninus paid great attention to the protection of the borders and maintaining peace with neighbors. Defensive structures, the so-called Antonine Walls, were hastily built along the borders.

Marcus Aurelius

After the death of Antoninus Pius, Rome found itself with two emperors — Marcus Aurelius (161–180) and Lucius Verus (161–169), the adopted sons of Antoninus. Discord between them, which Rome's enemies expected, was prevented thanks to the exceptional personal qualities of Aurelius. He tolerated his insignificant co-ruler for eight years, until the latter's death.

From this time, the division of power between co-emperors became a frequent phenomenon. Marcus Aurelius was one of the most educated people of his time, a Stoic philosopher, author of the work "Meditations".

Under Marcus Aurelius, the period of stable balance of power between the Roman Empire and the barbarian periphery came to an end. Starting from the time of Marcus Aurelius, Rome emerges as the defending side.

The Marcomannic Wars (167–180) were a prelude to the barbarian conquests of subsequent centuries. Crossing the middle Danube, the Germanic tribe of the Marcomanni, along with their allies — the Quadi, Sarmatians, and Iazyges — invaded the empire. The Roman state was weakened by the time due to the war with Parthia and the epidemic. Rome gathered all its forces. Even volunteer slaves and gladiators were mobilized. Both emperors personally went to war. All the remaining years of his rule, Marcus Aurelius spent on the northern border, fortifying it and fighting the barbarians who had invaded the empire. Part of them was pushed out, and the Roman government was forced to settle the other part on this side of the rampart as allies — foederati. Thus, the barbarians began not only to raid the empire but also to settle in its territory. In 180 AD, Marcus Aurelius died in Vindobona (now Vienna), where he was preparing for a new campaign against the Marcomanni.

Breaking the tradition of the Antonine dynasty, Marcus Aurelius bequeathed the imperial throne not to the choice of the Senate, but to his son Commodus (180–192), under whom the condition of the empire continued to deteriorate. The decline of central power is observed. Commodus ended the war with the Marcomanni, although the Romans were far from victory in 180 AD. Commodus himself, in contrast to his father, was a rough, dissolute man. Seeing the discontent of the nobility, he strove to appease the Praetorians and the Roman urban plebs: the Praetorians were given increased pay, and distributions and spectacles were arranged for the urban plebs. Favorites dominated the court, who eventually killed the emperor. A period of crisis was approaching, signaling a transition to the late empire.

Conclusions

Starting from the moment Nerva ascended the throne in 96 AD and ending with the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD, the Empire experienced an eighty-four-year period of peace under the rule of a tolerant, just government. During this time, wars were fought with the Parthians, Dacians, and Britons, but this happened far from Rome, in most cases, the battles were fought on enemy territory and hardly affected the Roman provinces. There were also disorders, of which the Jewish revolt during the reign of Hadrian was particularly serious, and sometimes rebellions started due to the fault of military leaders, as in the case when a capable commander of the Syrian legions in 175 AD received a false report about the death of Marcus Aurelius at the hands of the Marcomanni and decided to declare himself emperor. All these revolts were successfully suppressed and against the background of overall calm turned out to be no more than pinpricks.

However, in the 18th century, the English historian Edward Gibbon made the famous statement that in all of human history, never had so many people at the same time been as happy as in the Roman Empire during the reign of the Antonine dynasty. To some extent, he was right. If we take the territory of the Mediterranean as an example, materially life there was easier than ever during centuries of continuous continental wars when one state constantly attacked another. Moreover, during the reign of the Antonines, the situation in the Mediterranean was better than in many subsequent centuries, when it was torn apart by civil wars and tormented by invasions of barbarians or even later when it was divided into many small rival states.

Similar topics

Roman Empire, Roman Emperors, Reign of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty, Reign of the Flavian Dynasty, Marcus Ulpius Nerva Trajan