Helmets of the Celts

The helmet was an essential attribute for Celtic warriors. They underwent significant changes over time, giving rise to numerous subtypes. A vast number of simpler helmets, such as the Montefortino type, have been found, primarily made of bronze, although there are also discoveries made of iron. Additionally, richly decorated helmets have survived to this day, indicating their use by nobility or, judging by their well-preserved condition and non-optimized construction for combat, for ritual purposes.

In terms of technology, the Celts were one of the most advanced civilizations in antiquity, and many innovations, including in military equipment, were borrowed by other peoples. This also applied to helmets, as over time the Romans adopted and modified them according to their needs and traditions.

Most Celtic shields had an oval shape, although rectangular, hexagonal, and round examples can be found in images and archaeological findings. These depictions also indicate that shields were adorned with various symbols, animal motifs, or geometric ornamentation.

Archaeological finds

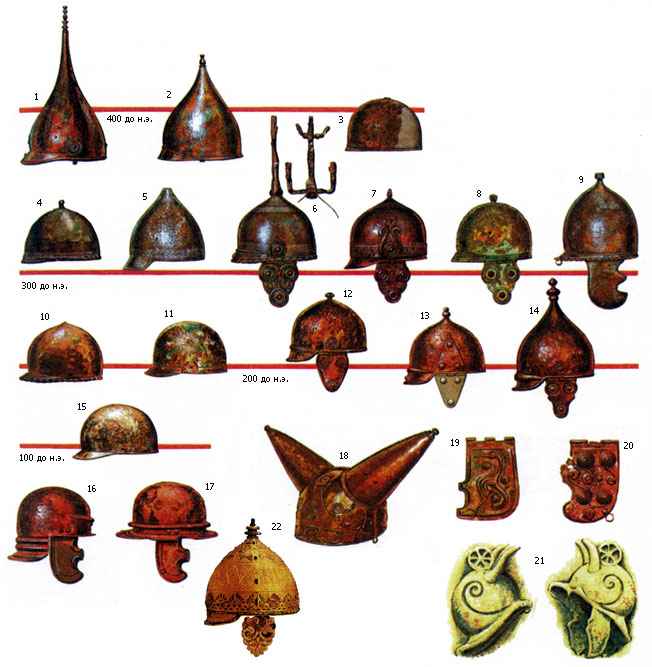

A multitude of helmets have been discovered in the region of Italy that was inhabited by the Senones, located along the Atlantic coast between Ancona and Rimini. All of them feature a neck guard at the back, designed to protect the neck. Helmets of this type are commonly referred to as Montefortino helmets, named after the burial site where they were first found. It is easy to trace the connection between this type of helmet and those used in France and Austria in the 5th century BCE (1, 2). They were made of bronze and had an elongated shape. It is likely that this type of helmet emerged in Italy along with the Senones.

There, it transformed into the Montefortino helmet, retaining the neck guard and a fairly long crest, although the helmet itself acquired a significantly more rounded shape. Figures 5, 6, and 7 depict helmets discovered in Senonian burials and date back to a period before 282 BCE, when this Celtic tribe was ultimately displaced by the Romans. They are typically attributed to the late 4th to early 3rd century BCE. Helmets retrieved from the Senonian burials were usually made entirely of iron or iron and bronze, with fully bronze examples being rare. Some of them had elaborate composite attachments for the crest, made of an iron holder fixed to the top of the helmet.

Likely, both sides of such a helmet were adorned with feather decorations, while a crest made of horsehair was positioned on the top. The cheek pieces of this type of helmet were almost always of a "triple-disc" shape (6) and were possibly borrowed from the Italians. Their style bears such a resemblance to Samnite breastplates that it is difficult to doubt their origin. In the 3rd century BCE, the shape of these cheek pieces simplified, becoming triangular with three "protrusions." The Italians quickly adopted the Montefortino helmet type. An example discovered in Bologna bears an Etruscan inscription, allowing its dating to the time before the Etruscans departed from the Po Valley in the mid-4th century BCE. Such helmets are also encountered in reliefs from a 4th-century BCE tomb in Cherveteri. The cheek pieces on both helmets have prominently expressed serrations. In Etruria, a "triple-disc" type was found as well, although it seems to have existed no later than the 4th century BCE. One specimen of a helmet with serrated cheek pieces was found in the Montefortino necropolis, but it is most likely of foreign origin (9).

1 - A bronze Celtic conical helmet from Apulia. The decorations on the helmet are Celtic, but the overall style is Apulian. Several helmets with intricately carved horn-like details made of thin sheet bronze have been discovered in Italy. Bari Museum. 2 - A horn from the same helmet. British Museum. 3 - A coin from France depicting a Celtic warrior with hair soaked in lime. 4 - A Celtic Negau-type helmet from the Alps. It is almost identical to the early Italic type, except for the crest-like protrusion. 4a - The inner part of the lower edge showing how the liner was attached. 5, 6 - Front and back views of a statue of a warrior from Gresan, near Nimes in southern France. This statue, which can be dated to the 4th century BCE, predates the Celtic period. The warrior either wears front and back breastplates secured with straps or a cuirass with decorative elements shaped like these plates. Nimes Museum. 7 - Detail of a belt buckle from Figure 5. 8 - A belt buckle of the same type as the one worn by the warrior from Gresan, found in Aleria, Corsica. This is not a Celtic type. 9, 10 - Two hooded heads from Saint-Anastasi, France. Nimes Museum. 11 - Sculptural depiction of chainmail with a shoulder covering from Entremont, southern France. This is a traditional Celtic type. 12 - Buckle from a similar depiction. 13 - Part of a Celtic chainmail with a fastening mechanism that held the covering. From Ciumesti, Romania. Scale 1:2. A, B, C - Three types of rings used in the Ciumesti chainmail, actual size. D - Cross-section of the fastening mechanism. 14 - Statue of a late-period Celtic warrior from Vaison-la-Romaine in southern France. He is clad in an Italian-style chainmail. 15 - Figurine of a Celtic warrior from northern Italy wearing chainmail of the Italian type. 16 - Sculptural depiction of chainmail from Pergamon, Turkey.

1 - A bronze Celtic conical helmet from Apulia. The decorations on the helmet are Celtic, but the overall style is Apulian. Several helmets with intricately carved horn-like details made of thin sheet bronze have been discovered in Italy. Bari Museum. 2 - A horn from the same helmet. British Museum. 3 - A coin from France depicting a Celtic warrior with hair soaked in lime. 4 - A Celtic Negau-type helmet from the Alps. It is almost identical to the early Italic type, except for the crest-like protrusion. 4a - The inner part of the lower edge showing how the liner was attached. 5, 6 - Front and back views of a statue of a warrior from Gresan, near Nimes in southern France. This statue, which can be dated to the 4th century BCE, predates the Celtic period. The warrior either wears front and back breastplates secured with straps or a cuirass with decorative elements shaped like these plates. Nimes Museum. 7 - Detail of a belt buckle from Figure 5. 8 - A belt buckle of the same type as the one worn by the warrior from Gresan, found in Aleria, Corsica. This is not a Celtic type. 9, 10 - Two hooded heads from Saint-Anastasi, France. Nimes Museum. 11 - Sculptural depiction of chainmail with a shoulder covering from Entremont, southern France. This is a traditional Celtic type. 12 - Buckle from a similar depiction. 13 - Part of a Celtic chainmail with a fastening mechanism that held the covering. From Ciumesti, Romania. Scale 1:2. A, B, C - Three types of rings used in the Ciumesti chainmail, actual size. D - Cross-section of the fastening mechanism. 14 - Statue of a late-period Celtic warrior from Vaison-la-Romaine in southern France. He is clad in an Italian-style chainmail. 15 - Figurine of a Celtic warrior from northern Italy wearing chainmail of the Italian type. 16 - Sculptural depiction of chainmail from Pergamon, Turkey.

The Montefortino type of helmet became widespread throughout the Celtic world: number 13 was found in Yugoslavia, and its almost complete Gallic counterpart is depicted on the Victory frieze in Pergamon. Although the Celts were largely pushed out of Italy by the first quarter of the 2nd century BCE, the Montefortino type continued to exist in the Alpine valleys. The specimens found there (12, 14) were exclusively made of iron and had a separately made neck guard that was later attached to the helmet. Cheekpieces deviated from the original design but still remained a characteristic feature of this type (14).

The Montefortino type was the most successful among all existing helmet designs and was used in the Roman army for nearly four centuries without undergoing significant changes. According to the most cautious estimates, approximately three to four million helmets of this type were manufactured.

There was a second type of helmet, very similar to the Montefortino type but without the "cone" on the crown (10, 11, 15). It is usually referred to as the "Coolus" type, named after the first specimen found in France from the 1st century BCE. Although it did not enjoy the same success as the Montefortino type, it gained considerable popularity in the 1st century BCE and possibly served as a precursor to the helmets worn by Roman legionaries in the 1st century CE. The origin of the Coolus type may be as ancient as the Montefortino type—one of such helmets was found in a Senonian burial, and a La Tène example can be dated to 400 BCE.

Some helmets feature wing-like decorations on the sides (7, 13). It appears that this type originated in Italy, most likely under the influence of winged elements seen on Samnite helmets. Such helmets were popular in the Balkans in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, and they are depicted on the Victory frieze in Pergamon, Asia Minor. One specimen was found in Amfreville, northern France, although it may have been imported from elsewhere.

The Orange Arch (21) depicts horned helmets that bring to mind the accounts of Diodorus. Referring back to the relief from Bormio, it can be speculated that these might have been standard-bearers' helmets. Several examples have been found in Italy with carved bronze details resembling horns. An extraordinary specimen of a horned ceremonial helmet was discovered in the Thames near Waterloo Bridge (18). Helmets adorned with animal figures, as described by Diodorus, are very rare. In fact, only one such example is known, found in Ciumești, Romania. It is a Batavian-type helmet (13) with a bird depicted on the apex. The outspread wings of the bird were attached to hinges, suggesting that they flapped while the helmet's owner charged into battle.

In several Celtic burials in northern Italy, Etruscan Negau-type helmets were found. The fact that the Celts adopted this type is confirmed by the discovery of several Negau helmets of Celtic form in the Central Alps.

Two new types of helmets emerged in the 1st century BCE. They are closely related to each other and are usually grouped under the Agde-Port type. The Agde type (17) resembles a pot-shaped hat with brims, while the Port type has a similarly shaped "pot" with a relatively large neck guard that was attached to the helmet (16). Both helmets featured a new type of cheekpiece, later adopted by the Romans. The Port type directly served as the prototype for the Gallic Imperial helmet of the 1st century CE. Examples of such helmets, made entirely of iron, have been found in northern Yugoslavia, the Central Alps, Switzerland, central and southwestern France. The locations where they were discovered share one characteristic—they are situated along the borders of Roman territories from the beginning of the 1st century BCE.

Cheekpieces of the Celtic type from Alesia in central France, dating to the 1st century BCE (20), represent a peculiar mixture of the classical Italian type with "cones" and the old "triple-disc" type. Similar characteristics are found in cheekpieces from an earlier period found in northern Yugoslavia (19). There are also known findings of conical helmets of the Greco-Italic type with Celtic decorations. All of them seem to originate from Apulia, an area in southern Italy. Decorative wheel-like elements placed on the apex of the helmets are nearly identical to those depicted on the Orange Arch.

Even in northern Italy, where a significant number of helmets are found, most Celtic warriors probably did not possess one. Diodorus informs us that these warriors would plaster their heads with lime and then comb their hair toward the nape to resemble a horse's mane. This hairstyle is depicted on several coins. The attempt to make the hair stand up, similar to the bristling fur of an enraged animal, dates back to very ancient times. It is possible that this is how the crest made of horsehair on helmets originated.

Related topics

Gallery

Gallery