Ancient Celts

The Celts (Greek: Κελτοί, Latin: Celtae) were tribes of Indo-European origin, closely connected by language and material culture, who in ancient times occupied vast territories in Western and Central Europe.

The Celts built fortified settlements known as oppida, with stone buildings and walls. Over time, these evolved into fortified cities and trade-craft centers, such as Bibracte, Gergovia, Alesia, and Stradonice. Thanks to this, Celtic craftsmanship was at an advanced level for that era.

Celtic history is divided into several periods, the most popular for reconstruction being the "La Tène":

- La Tène I (450–250 BC)

- La Tène II (250–120 BC)

- La Tène III (120–50 BC)

Contacts with Ancient Civilizations

The Celts were one of the most warlike peoples of ancient Europe. Before battle, they would issue deafening shouts and blow war trumpets called carnyxes, whose flared ends were shaped like animal heads to intimidate their enemies.

The Celts spread across almost all of Western Europe from southern Germany. By the beginning of the 5th century BC, they were living in what is now Austria, Switzerland, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of France, Spain, and Britain. In the following century, they crossed the Alps and invaded northern Italy. The first tribe to arrive in the Po Valley was the Insubres, who settled in the Lombardy region and made Milan their capital. They were followed by the Boii, Lingones, Cenomani, and other tribes, who conquered much of the Po Valley and eventually drove the Etruscans back over the Apennines. The last of the arriving tribes were the Senones, who moved down to the Adriatic and settled along the coast north of Ancona. In 390 BC, this tribe achieved something that no one else would for a thousand years afterward — they sacked Rome!

The name "Celts," as we use it today, comes from the Greek keltoi, while the Romans called the people who came from the Po Valley and France "Gauls" (Galli). During the 4th century, the Celts began moving into the Balkans, and by the early 3rd century, they took advantage of the absence of strong power in Macedonia and Thrace at the time. After ravaging both countries, they invaded Asia Minor and finally settled in Galatia, with these last tribes being commonly known as Galatians.

Throughout the 4th century, the Gauls frequently launched devastating raids on the lands of central Italy. The Etruscans, Latins, and Samnites usually managed to repel them, and the Gauls often retreated to Apulia, where they may have established permanent settlements.

As they spread, the Celts intermingled with local tribes like the Iberians, Ligurians, Illyrians, and Thracians, though some tribes managed to preserve their identity for a long time (such as the Lingones and Boii), which contributed to their small numbers. In 58 BC, according to Julius Caesar, there were 263,000 Helvetii and only 32,000 Boii (this point is disputed by many historians, as the Boii were brutally crushed by the Dacian king Burebista around 60 BC). The Celts of southern France developed in close interaction with ancient city-states, which led to their higher cultural level. Driven out by the Romans from northern Italy (Cisalpine Gaul) in the 2nd century BC, the Celts settled in central and northwestern Bohemia (named after the Boii tribe, who gave the region its name, Boiohaemum — homeland of the Boii).

The most numerous Celtic tribes were the Helvetii, Belgae, and Arverni. The most significant were the Helvetii, Boii, Senones, Bituriges, and Volcae.

No other people were treated by the Romans as the Celts were. The Romans systematically massacred them in northern Italy, Spain, and France. The recapture of the Po Valley, which occurred after the war with Hannibal, was accompanied by such brutality that by the mid-2nd century BC, Polybius could say that the Celts remained "in only a few places beyond the Alps."

Unfortunately, most of what we know about the Celts comes from their enemies — the Greeks and Romans. Diodorus, the Sicilian historian, vividly described the brightly colored clothing of Celtic warriors, their long mustaches, and hair that they soaked in lime to make it stand up like a horse's mane.

At first, the Romans feared the Celts, who seemed like giants compared to them. However, over time, as they learned the Celts' weaknesses and how to exploit them, the Romans came to disdain the unruly barbarians. This attitude is well reflected in Livy's account of the Celtic wars. Yet, despite this disdain, when led by a competent commander, the Celts were formidable warriors. They made up half of Hannibal's army, which for 15 years defeated Rome's legions. Later, the Romans recognized the value of these people, and they would go on to fill the ranks of the Roman army for centuries.

Internecine wars constantly weakened the Celts, facilitating invasions by the Germanic tribes from the east and the Romans from the south. The Germans pushed some of the Celts back beyond the Rhine in the 1st century BC. Julius Caesar conquered all of Gaul from 58 BC to 51 BC. Under Augustus, the Romans conquered areas along the upper Danube, northern Spain, and Galatia, and under Claudius (mid-1st century AD), they conquered much of Britain. The Celts who remained within the Roman Empire were Romanized.

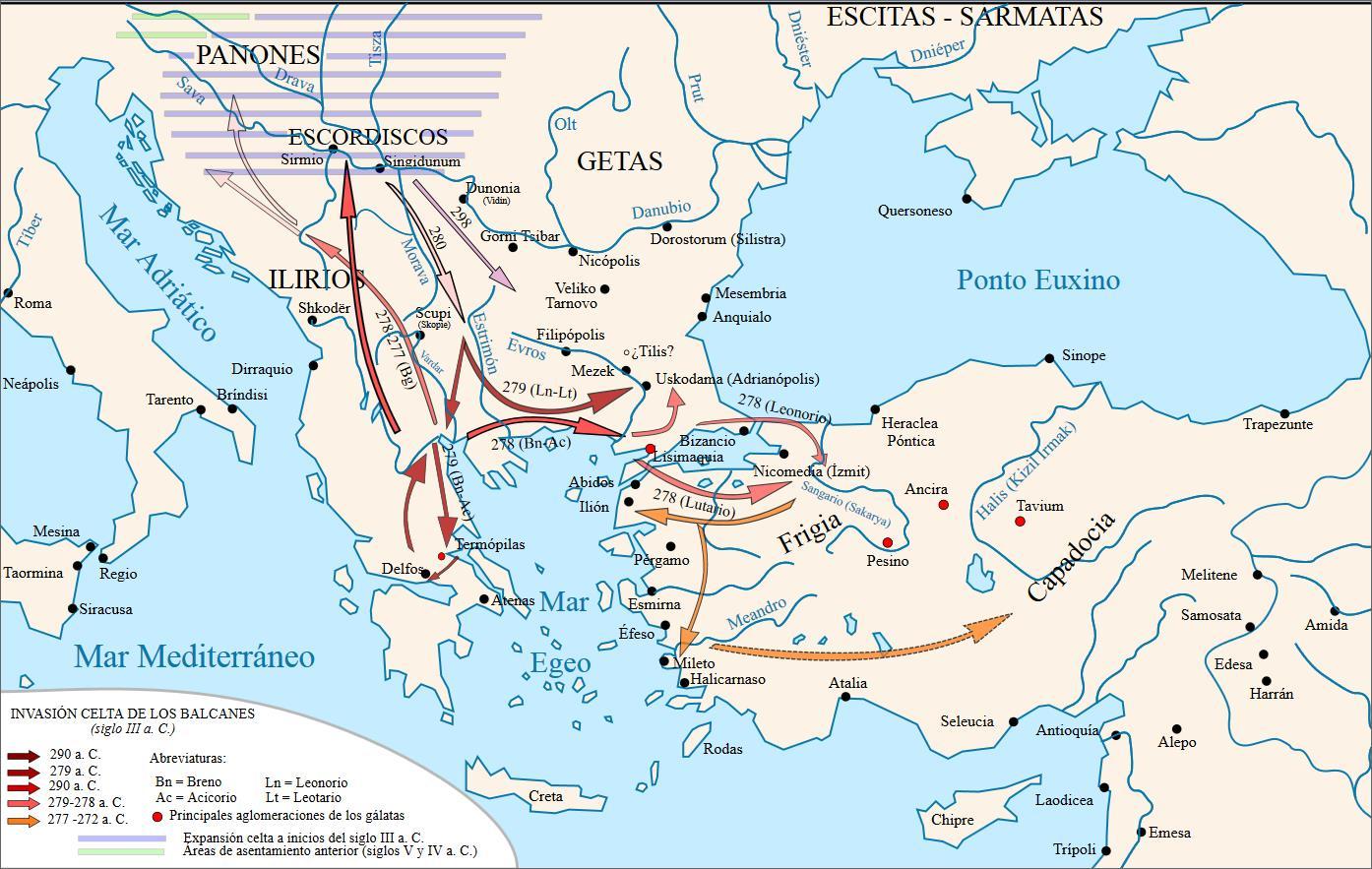

Celtic invasion of the Celts into the Balkans, their raiding expeditions against Thrace, Macedonia, and Greece, and their invasion of Asia Minor.

Celtic invasion of the Celts into the Balkans, their raiding expeditions against Thrace, Macedonia, and Greece, and their invasion of Asia Minor.

Warriors of the Ancient Celts

Most early societies, including archaic Greece and Rome, had a separate class of warriors, and the Celts were no exception. Their warriors came from social groups that can be characterized as the middle and upper strata of society. They fought in battles, while the poor, according to Diodorus, served as armor-bearers or chariot drivers.

A Celtic warrior was heroic in every sense of the word. He did not value his life too highly. He lived for war, but his unrestrained praise of bravery, combined with a lack of discipline, often led to defeat. In the fifth book of his work, Diodorus provides a detailed and possibly accurate description of a Celtic warrior. However, it should be noted that 350 years passed between Rome's first encounter with the Celts at the Battle of the Allia and Caesar's conquest of Gaul, the period when Diodorus was writing. Much had changed in weaponry and tactics during that time. Here is a brief summary of Diodorus's description, which at times seems anachronistic, followed by a discussion of those changes. According to Diodorus, a Celtic warrior was armed with a long sword worn on a chain on the right side, as well as a spear or javelin. Although most warriors preferred to fight naked, some wore chainmail and a bronze helmet. The latter was often decorated with relief figures, horns, or attachments depicting animals or birds. The warrior carried a long shield, as tall as a man, which could be decorated with relief bronze figures.

In battles against cavalry, the Celts used chariots. Entering battle in his two-horse chariot, the warrior would first hurl javelins and then, like Homer's heroes, dismount and fight with a sword. Before the battle, warriors (Diodorus refers to them as champions) would step forward, brandishing their weapons to instill fear in the enemy, and challenge the bravest of their opponents to single combat. If the challenge was accepted, the champion might break into a song in true barbarian spirit, in which he praised the deeds of his ancestors, boasted of his own exploits, and insulted his opponent.

Romans honored their commanders who accepted challenges and defeated Celtic duelists in single combat. These commanders were granted the privilege of dedicating the best part of their spoils (prima spolia) to the temple of Jupiter Feretrius ("Bringer of Spoils" or "Bearer of Victory"). There were also secunda spolia and tertia spolia (second and third parts of the dedicated spoils), depending on the rank of the victor. It was said that Titus Manlius, who lived in the 4th century BCE, managed to defeat a huge Celt in single combat and tore off his gold torc (torques), thus earning the nickname "Torquatus." The most notable of these heroes was Marcus Claudius Marcellus, who killed the Gallic chieftain Viridomarus in single combat in 222 BCE. He then became the most successful of all Roman commanders who fought Hannibal during his Italian campaign.

After killing an opponent, a Celtic warrior would cut off the enemy's head and hang it around his horse's neck. He could then strip the armor from the fallen foe and order a squire to carry the bloodstained trophy while he sang a war song over the defeated enemy. The trophy was then nailed to the wall of his dwelling, and the heads of the most distinguished enemies were embalmed in cedar oil. The head of Consul Lucius Postumius, killed by the Celts in the Po valley in 216 BCE, was displayed in a temple. Excavations at Entremont have shown that severed heads were not just trophies but part of a religious ritual – they were placed in special niches around a ceremonial entrance.

Before moving on to a detailed description of Celtic equipment, a few general remarks should be made about Celtic warfare. All ancient authors agree that the Celts did not highly value strategy and tactics. Polybius criticizes them for lacking a campaign plan or any particular judgment on how to conduct one; he adds that everything they did was driven by immediate impulses. This may give the impression that the Celts fought like a disorganized mob, swarming all at once. However, the presence of standards and horns among Celtic trophies, depicted on the Arch of Orange, suggests a certain degree of military organization. Caesar describes how pilum javelins pierced the tightly packed Celtic shields. This could only refer to a dense formation similar to a phalanx, which was not typically characteristic of the Celts, suggesting they used different formations. This hypothesis is supported by Polybius' description of the Battle of Telamon, where the Celts, caught between two Roman armies, formed a back-to-back formation, facing both sides with a depth of four men. Polybius admires this formation and notes that even in his day, 75 years later, people still debated which side had the stronger position. No Celtic army could be attacked from the rear, and, having no way to retreat, the Celts were forced to fight to the death.

The Romans were indeed frightened by this flawless formation and the wild din and noise made by the Celts. The Celts had countless horn players and trumpeters, and all the warriors shouted their battle cries simultaneously. In conclusion, Polybius states that the Celts were inferior to the Romans only in weaponry, as they had lower quality swords and shields.

Men's Celtic Clothing

Basic elements of Celtic men's clothing:

For Celtic warriors, the following elements are also added::

- Spear (both melee and throwing)

Celtic Women's Clothing

Basic elements of Celtic women's clothing:

Reconstruction

When reconstructing the Celts, it's important to consider historical periods. The best choice is La Tène III (120–50 BCE). It should be noted that there are few textile finds, which means that clothing would overlap significantly over time. However, there are many findings of jewelry, weapons, and other metal objects. Therefore, when creating an image, the most attention should be paid to the sword and helmet. For a female image, it is essential to focus on jewelry.

Related topics

Celtic shoes, Peplos, Celtic skirts, Celtic shirts, Celtic swords, Celtic helmets

Literature

Celts-an article from the Great Soviet Encyclopedia. Belova N. N., Mongayt A. L..

Gauls or Celts // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

The Celts // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

Birkhahn Helmut. Celty: Istoriya i kul'tura [The Celts: History and Culture], translated from German by N. Y. Chekhonadskaya, Moscow: Agraf, 2007, 512 p. (Heritage of the Celts. Research). — ISBN 978-57784-0346-8.

Bruno Jean-Louis. Gauls / Translated from French by A. A. Rodionova, Moscow: Veche, 2011, 400 p.: ill. (Guides of Civilizations). — ISBN 978-5-9533-4656-6.

Connolly P. Greece and Rome. Encyclopedia of Military History. Eksmo-Press. Moscow, 2000. Translated by S. Lopukhova and A. Khromova.

Celts Lords of Battles-Stephen Allen. pdf

Celtic warriors from Szabadi Somogy coun.pdf

Celtic Design Spiral Patterns - Aidan Meehan.pdf

Gallery

Gallery

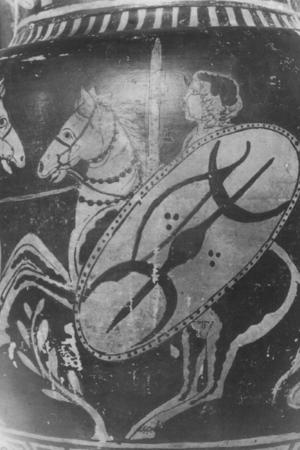

Galatian Horseman unseating his opponent. Terracotta relief from a vase in Canosa, late 3rd century BCE.

Galatian Horseman unseating his opponent. Terracotta relief from a vase in Canosa, late 3rd century BCE. Frieze with Galatian Trophies from the propylaea of the Pergamon Library. It depicts Galatian shields of characteristic shape, chainmail, spears, and a signal horn with a bull's head bell. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, 2nd century BCE.

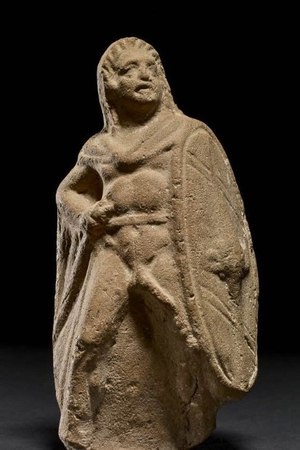

Frieze with Galatian Trophies from the propylaea of the Pergamon Library. It depicts Galatian shields of characteristic shape, chainmail, spears, and a signal horn with a bull's head bell. Pergamon Museum, Berlin, 2nd century BCE. Stele from Bormio in northern Italy, depicting a Gallic trumpeter and a standard-bearer, 4th-2nd century BCE.

Stele from Bormio in northern Italy, depicting a Gallic trumpeter and a standard-bearer, 4th-2nd century BCE.