Gallic Invasion

The Gallic invasion was one of the most devastating events for the Roman Republic, as well as for other peoples of the Italian Peninsula.

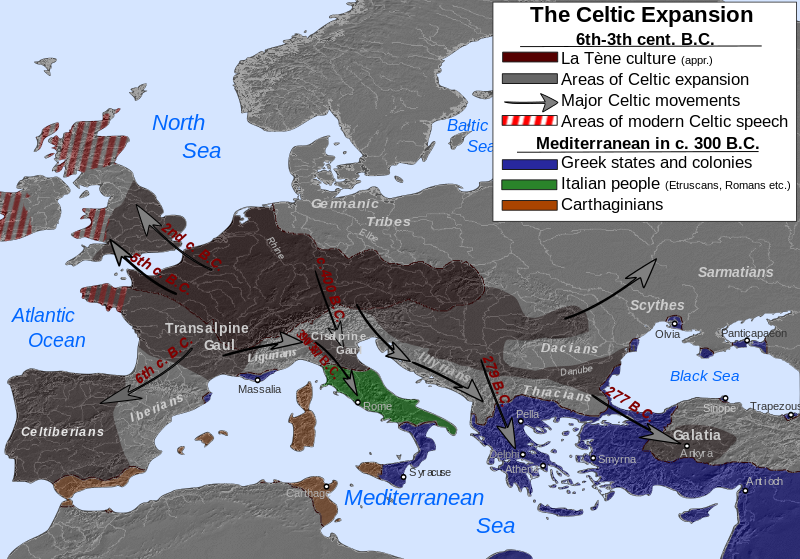

The first encounters between the Gauls and the Romans date back to the 6th century BCE, when the Insubres, Bituriges, Aedui, Arverni, and other Gallic tribes, led by Bellovesus, invaded Northern Italy and Western Etruria. Another of their armies, under the command of Elitovius, took control of the area from Como to Bergamo. Since then, Northern Italy became known as Cisalpine Gaul. A third Gallic invasion, led by Sigovesus, spread from the land of the Sequani into Illyria and Pannonia. In 391 BCE, the Gauls besieged the city of Clusium, west of Perusia and Lake Trasimene. The besieged inhabitants appealed to Rome for help, which became the pretext for the first Gallic campaign against Rome.

Celtic Tribal Expansion in the 6th–3rd Centuries BCE

Celtic Tribal Expansion in the 6th–3rd Centuries BCE

The devastation caused by the Celts (Gauls) in much of Italy and the destruction of Rome were significant events that inevitably found a strong resonance in ancient historiography, both contemporary to these events and later. However, these historical facts, reflected in the works of many generations of Greek and Roman writers, became distorted. A significant role in these distortions was played by a patriotic legend, through which Roman historians of a later period, when Rome had already become a world power, sought to mitigate the bitterness of the catastrophic defeat in 390 BCE. It is therefore difficult to unravel the mass of various and often contradictory reports. Many significant details still lack a unified scholarly perspective, and it is unlikely that such a consensus will ever be reached.

According to the dominant ancient tradition, accepted by modern scholarship, the Gauls in the late 5th century BCE crossed the Alpine passes and invaded Northern Italy in successive waves, which was then inhabited by Ligurians and Etruscans. In fierce clashes, they partly exterminated the local population, partly pushed them into the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Apennines, and partly intermingled with them. Along the coast of the Adriatic Sea, the Gallic tribe of the Senones even penetrated into Northern Umbria. Only the region of the Veneti, north of the lower Po River, escaped the Gallic invasion.

In the late 390s BCE, one of the Gallic tribes, numbering several tens of thousands of people and led by Brennus, appeared in Central Etruria and besieged the city of Clusium. It is impossible to determine exactly which tribe this was, as sources differ on this account. The Clusians sought help from Rome. In modern scholarship, there are skeptical voices claiming that this is a fabrication and that at that time Rome had no interest in the affairs of Central Etruria. However, if we consider the successes the Romans had achieved in wars with the southern Etruscans, Clusium's appeal to its powerful neighbor seems plausible.

The Roman government sent an embassy to the Gauls consisting of three representatives of the noble Fabii family, tasked with settling the matter peacefully. However, the envoys failed in their mission: they violated neutrality, intervened in the conflict on the side of the Clusians, and one of them even killed a Gallic leader. The Gauls broke off negotiations and appealed to Rome, demanding the culprits be handed over. The Roman government, yielding to pressure from the nobility, not only refused this demand but also elected the Fabii as military tribunes for the following year.

Enraged, the barbarians lifted the siege of Clusium and swiftly marched on Rome. Armed with massive shields and long swords, and shouting wild cries that struck fear into their enemies, they crushed the Roman army in a single blow on July 18, 390 BCE, on the banks of the Allia River, a small tributary of the Tiber that flowed into it from the left side near the city of Fidenae.

Terracotta figurine of fleeing Celtic warriors. Civitalba (Marche), Italy. 3rd century BCE.

Terracotta figurine of fleeing Celtic warriors. Civitalba (Marche), Italy. 3rd century BCE.

The exact date and location of the Battle of the Allia have not been definitively established. The Roman version of the tradition (as recorded by Livy) dates it to 390 BCE, while the Greek version (as given by Polybius and Diodorus) places it in 387 BCE. As for the specific day, there is no dispute, as July 18th (dies Alliensis) was marked as a day of national mourning in Rome. There are also two versions regarding the location of the Allia. According to Livy (V, 37), the Allia flowed into the Tiber from the left side, while Diodorus (XIV, 114) states that the Romans fought the Gauls after crossing the Tiber. Therefore, modern scholarship is divided in determining the location of the Allia: some scholars believe it was a left tributary of the Tiber, while others argue it was a right tributary. General strategic considerations suggest that the Allia was a left tributary. The commonly accepted year is 390 BCE, although the mentions by Polybius and Diodorus may be more reliable.

The defeated Roman army scattered across the surrounding areas, with part of it retreating to Rome. The city was in a state of panic. Most of the population, along with the most revered religious artifacts, managed to evacuate to neighboring cities. Only a small portion of the army, along with the younger members of the Senate, took refuge on the Capitoline Hill. The elder senators refused to leave their homes and remained in their dwellings.

It is likely that Rome was so poorly fortified at this time that it was impossible to defend. The Gauls appeared in the city the next day (according to other reports, only after three days). The unarmed city was looted and burned, and the remaining inhabitants were slaughtered.

The patriotic Roman legend vividly describes how the remaining senators in the lower city met their deaths. The most distinguished of them, dressed in ceremonial robes, sat on ivory chairs in the vestibules of their homes. At first, the Gauls looked upon the motionless figures in amazement, mistaking them for statues. One of the barbarians dared to touch one of the elders by his long beard. The elder struck him with his staff, which served as a signal for a general massacre.

After finishing with the city, the Gauls turned their attention to the Capitoline Hill. An attempt to take the citadel by storm failed due to the steep slopes of the hill. The enemies then began a siege.

Tradition has preserved for us a story from this siege that became world-famous. One night, a group of Gauls climbed the steep slope of the Capitoline Hill. The barbarians climbed so quietly that not only the guards but even the dogs heard nothing. Only the geese, sacred to the goddess Juno, raised an alarm. The noise woke the former consul Marcus Manlius, whose house was located on the Capitoline. He rushed to the edge and threw down the first Gaul who had reached the top. The awakened guards came to Manlius's aid, and all the Gauls met the same fate as their leader. Marcus Manlius became a popular hero and was given the epithet "Capitolinus," although this did not prevent him from later falling victim to class conflict. This story is so distinctive that it could not have been entirely fabricated. It likely has a basis in real events.

The siege of the Capitoline Hill lasted for seven months. The besieged suffered from hunger, but the situation of the besiegers was not much better. Due to a lack of provisions and the summer heat, diseases began to spread among them. Additionally, the Gauls received news that the Veneti had invaded their territory. Therefore, when the Romans proposed peace negotiations, the Gauls readily agreed. It was agreed that they would leave Rome after being paid 1,000 pounds of gold. After receiving the ransom, the enemies did indeed leave the Roman territory and were attacked during their retreat by a Roman army that had been reformed outside Rome during the siege of the Capitoline. This army was led by Marcus Furius Camillus, the hero of the Veii war. The Gauls, it seems, suffered some losses.

The patriotic sentiment of the Romans could not reconcile with the shameful events of 390 BCE, and a later version of these events, which has remained in history, was crafted. When the gold was being weighed, the Roman representatives pointed out to the Gauls that their scales were incorrect and began to protest. The Gallic leader Brennus then placed his heavy sword on the scale with the words: "Woe to the vanquished!" ("Vae victis!"). At this dramatic moment, Camillus appeared with his army. The Gauls were utterly defeated, and the gold was reclaimed.

The departure of the Gauls did not mean that all danger for Rome had passed. Several times after this, they invaded Latium and penetrated as far as Southern Italy, but they were never able to capture Rome again. It was only in the late 370s BCE that the Romans concluded a peace with them.

One of the most sorrowful pages in Roman history — the capture of Rome by the Gauls in 390 BCE — is shrouded in a sea of legends meant to somewhat mitigate the shame of the defeat. The legend of how the geese saved Rome became world-famous. Livy (V, 47) recounts it as follows:

"In Rome, meanwhile, the fortress and the Capitoline were in great danger. The Gauls either noticed human footprints where a messenger from Veii had passed, or they themselves had observed that at the temple of Carmenta, the ascent to the rock began with a gentle slope. Under the cover of night, they first sent an unarmed scout ahead to explore the way, and then all began to climb. Where it was steep, they passed their weapons hand-to-hand; some placed their shoulders under others, who climbed up and then pulled up the first; if necessary, they all helped one another and made their way to the summit so quietly that they not only deceived the vigilance of the guards but did not even wake the dogs, animals so alert to the sounds of the night. But their approach did not escape the geese, which, despite the acute shortage of food, had not been eaten because they were sacred to Juno. This circumstance proved to be their salvation. Awakened by the noise and flapping of wings, Marcus Manlius, a renowned warrior who had been consul three years earlier, grabbed his weapons and, while calling others to arms, rushed forward amid the general confusion and struck down the first Gaul who had already reached the summit. Tumbling down, the Gaul in his fall dragged down those who were climbing after him, and Manlius began to strike at the rest—who, in fear, dropped their weapons and clung to the rocks with their hands. But now the other Romans had gathered: they began hurling spears and stones, pushing the enemy off the cliffs. Amidst the general collapse, the Gallic squad tumbled into the abyss and fell. When the alarm subsided, everyone tried to sleep out the rest of the night, though with the agitation that prevailed in their minds, it was no easy task—the recent danger still weighed heavily. At dawn, the trumpet called the soldiers to a council with the tribunes: it was necessary to reward both the heroic deed and the crime. First of all, Manlius was thanked for his courage—he was given gifts by the military tribunes and, by unanimous decision of all the soldiers, each brought him half a pound of spelt and a quarter of a pint of wine to his home in the fortress. And though this might seem a mere trifle, in the conditions of famine, it was the greatest proof of love, for to honor a single man, each had to take from his own essential needs, depriving himself of food."