Minoan Crete

Periodization

I. Early Minoan period. 30-21/20 centuries BC. Mastery of bronze, the emergence of the potter's wheel and the institution of slavery.

II. Middle Minoan period or "Age of the Old Palaces" 20-18 centuries BC. The emergence of settlements (city-states) grouped around courts (Knossos, Phaistos, Kato Zakros).

III. Late Minoan period or "Age of the New Palaces" 17-12 centuries BC.

1) 17-14 centuries BC. The flourishing of Cretan civilization. Unification of Crete and creation of a maritime state. 2) 14-12 centuries BC. The decline of Cretan civilization. Volcanic eruption on the island of Thera (modern Santorini), the conquest of the island by the Greek Achaeans.

Discovery of the Minoan civilization

Until the mid-19th century, the history of ancient Greece was studied from the 8th century BC (from the Archaic period). The history of an earlier period was known only from the myths and tales of ancient authors, such as Plutarch, Thucydides, and Diodorus Siculus, who tell us the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur. Until the 19th century, scholars ignored these stories, despite the fact that ruins of ancient structures were found in many places in Greece, about the origin of which the local residents composed legends. The idea that myths might reflect real historical reality was almost not considered by scholars of that time until the 1870s. This period can be considered a turning point in the study of ancient Greek history. This is connected with the beginning of excavations by H. Schliemann of Troy in Asia Minor and A. Evans of the Knossos Palace, which allowed to prove the existence here of an earlier Cretan-Mycenaean civilization (3-2 thousand BC).

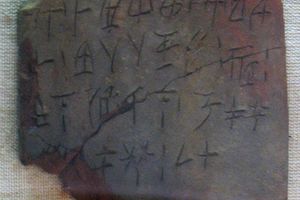

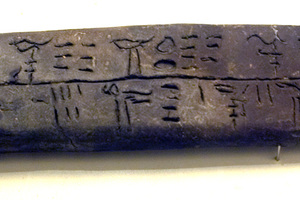

It should be noted that many tablets with inscriptions, mostly of an economic nature, were found on Crete. We are talking about so-called Linear A and Linear B scripts. The first has not been deciphered to this day. But Linear B was deciphered after several unsuccessful attempts, including those made by A. Evans. The script was deciphered in 1950-1953 by Michael Ventris with the participation of John Chadwick.

Economic development

The ancient focus of civilization in Europe was the island of Crete. At the turn of the 3rd-2nd millennium BC, the Minoan civilization emerged here, which received its name from the mythical monster Minotaur. As early as the beginning of the 3rd millennium BC, the production of copper and bronze was established on the island. Among the reasons for the flourishing of the Minoan culture, a number of researchers name the trade in tin, necessary for obtaining high-quality bronze, the most important material of this era, which subsequently got the name Bronze Age. From the Early Minoan period, there is evidence of the appearance of "colonies" of Minoan culture on the Cycladic Islands, the island of Rhodes, in the Miletus region. At the same time, changes also occur in agriculture. Its basis becomes polycultural farming or the so-called "Mediterranean triad" appears, which involves the cultivation of cereals (mainly barley), grapes, and olives. The result of this economic shift was the growth of the productivity of agricultural labor, as well as the appearance of a reserve fund of agricultural products, which provided food for people not engaged in agriculture. This allowed the development of professional specialization in various sectors of production. Also, thanks to this reserve fund, the population was provided with food in years of poor harvest. From the 3rd millennium BC, maritime trade with mainland Greece, Syria, Egypt, the Cycladic Islands, Asia Minor actively developed.

Political Structure

With the progress in the economy, the island's population grew in the most fertile regions (Knossos, Phaistos), and social differentiation of Cretan society also appeared. On the one hand, within communities, a layer of nobility is distinguished, which includes priests and clan leaders, who occupy a privileged position in relation to the main mass of the population. On the other hand, slaves, who mostly became captives. At this period, new forms of political relationships appear. The strongest communities begin to subordinate neighboring, weaker communities. Larger communities internally consolidate and have a clear political organization. As a result of these processes, "palatial" states begin to appear, such as Knossos, Phaistos, Kato Zakros. This is the epoch of the "old" and "new" palaces, covering the 20th-14th centuries BC. During this period, a king stood at the top of the social structure, according to modern researchers in Crete there was a theocracy (a type of monarchy, in which secular and spiritual power belonged to the same person). The person of the king was considered inviolable and sacred, he could not be seen by "mere mortals", before meeting with him in the throne room it was necessary to undergo a purification ritual. Perhaps that's why among the numerous works of Minoan art we cannot accurately assert if there is an image of a ruler. In addition to religious functions, the king had administrative ones, he collected taxes and duties, managed property. Further in the social hierarchy followed the nobility and royal administration, the middle class i.e. merchants and craftsmen, free peasants who paid taxes, and slaves.

In the future, Greece will move from centralized and single royal power to democratic governance, small, private peasant farms will replace large agricultural holdings. The role of the lower strata of the population will increase, and that of the aristocracy, on the contrary, will decrease.

Religion

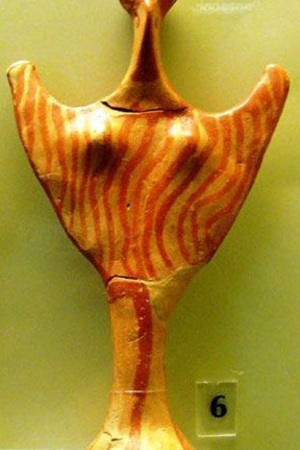

The cult of the female supreme deity occupied a central place in Crete. The goddess's name is unknown, but inscriptions refer to the goddess as the mistress. Based on Cretan art, we can assert that she had several images. We can see her as the mistress of beasts and a huntress, a patroness of vegetation, trees were dedicated to her, in addition to this birds, most often doves, are associated with her cult. Sometimes she appears to us as the queen of the underworld, holding snakes in her hands. Such images have been found in the Palace of Knossos - these are figurines made of faience or ivory, richly decorated with gold. In poor houses, similar images have been found, only made of clay.

In the Cretan pantheon, we also see a male deity, embodying the destructive forces of nature. It is worth noting here that Crete often suffered various cataclysms: earthquakes, sea storms, thunderstorms, heavy rains, drought years, famine, and epidemics. These phenomena were transformed in the consciousness of the Minoans into the image of a bull god. On some seals, he is depicted as a fantastic creature - a man with a bull's head. (This reminds of the later Greek myth of the Minotaur). On the island, the symbol of the male deity was Labrys - a double axe, the image of which often appears in Cretan art.

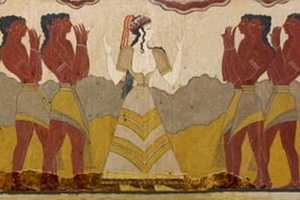

Apparently, women played a leading role in religious ceremonies. Men rarely appear in cult scenes and only appear in the later period.

No monumental temple buildings have been found in Crete. Sanctuaries with cult images and sacrificial tables have been found in the homes of the middle class and in palaces. Apparently, there were rural sanctuaries, which consisted of an altar and a group of sacred trees.

Culture and art

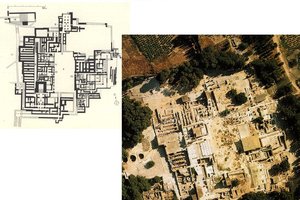

Now let's move on to considering Minoan culture and art using the example of the Palace of Knossos. Knossos is located in the central part of northern Crete, known as the capital of the island and the residence of King Minos. Here, according to the myth, Theseus killed the Minotaur. The architecture of the Palace of Knossos reveals characteristic features of Cretan construction: liveliness of lines, light courtyards, openness of rooms, ventilation and light holes (presumably they could be drawn with a curtain), many halls connected by corridors around the central courtyard, columns tapering to the bottom.

During the excavation of the Palace of Knossos, started by A. Evans in 1900, traces of the first palace were found, built around 2000 BC and collapsed in an earthquake around 1700 BC. A second, more spacious palace, built on the ruins, was later also destroyed as a result of new underground tremors around 1400 BC. After that, only some rooms were re-adapted for habitation, but they were completely abandoned around 1000 BC. The majestic ruins of the second palace, dating back to the peak of Cretan civilization (17-15 centuries BC), rise on a small hill, which is the highest point of the archaeological zone. The exterior appears not with straight facades, but with recesses and projections.

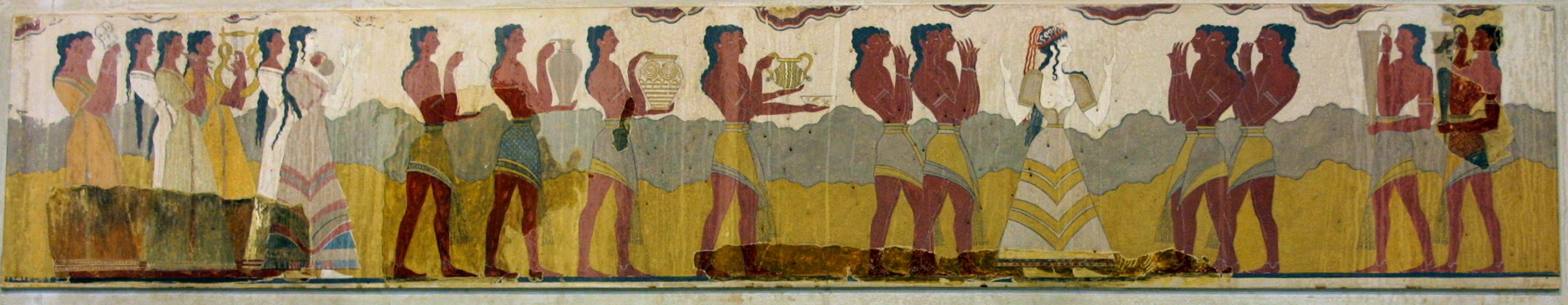

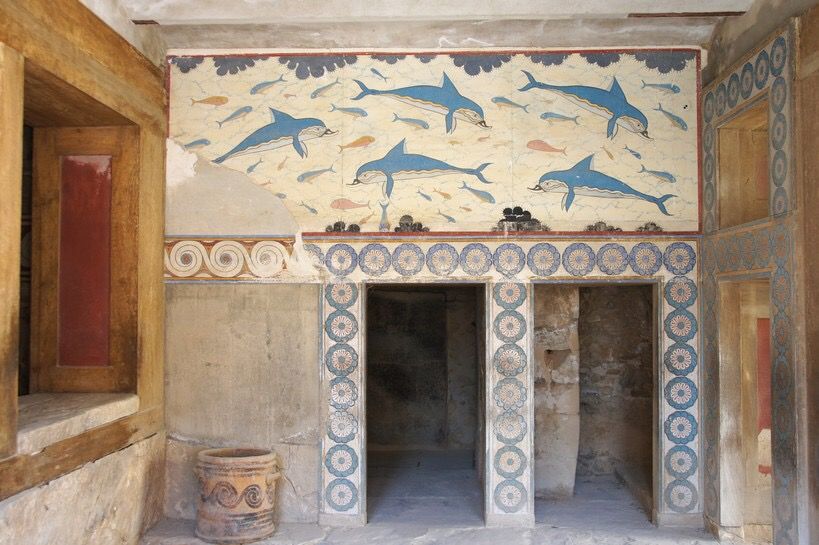

You can enter the palace through a monumental door with a column in the center and go along a narrow L-shaped corridor, named the Procession corridor after the huge frescoes depicting a procession of cupbearers, which decorated the hall. Thus, we proceed to the porticos, which in turn lead to the staircase of the upper floors. The palace was two or more stories high. Further, following a zigzag path, you can enter the central courtyard, which surrounds the entire palace. To the west, the halls of representation, the sacred complex and the throne room, built around 1450 BC, open up, where you can admire the ancient throne made of plaster and restored original frescoes depicting griffins, facing each other with plant motifs. Behind them are 22 rooms intended for warehouses. The passage in the center of the eastern part of the courtyard leads to numerous private quarters, and the descent - to the columned hall, serving as a vestibule; from here, to the north - to the district of laboratories and to the warehouse of large clay vessels; to the south - to the royal quarters: the Hall of the Double Axe with three porticos and corresponding light shafts, the queen's megaron with a copy of the dolphin fresco: a small toilet has been preserved nearby. The Palace of Knossos had plumbing and sewerage. To the south of the megaron are other rooms, apparently intended for the palace administration: in one of them, clay tablets with Linear B script were found.

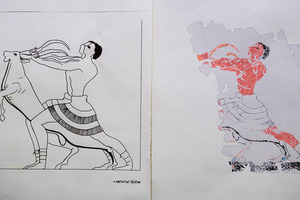

On the northern side of the central courtyard, there is also an entrance to a long corridor leading to the large Customs Hall with two rows of columns, and next to it are the northern propylaea, where another warehouse of tablets with linear script was discovered. On the bastion, one can see the famous row of bull pits, restored by A. Evans, where there is a copy of a fresco depicting a bullish bull, which has become a symbol of Minoan power. Judging by the found monuments of architecture and art, we can see the extraordinary cultural level reached by the inhabitants of this palace. The bulk of the population of Crete lived in small settlements in the vicinity of the palaces, for example, Gournia. These villages with small, adobe houses, closely huddled together, contrasted sharply with the multi-storey and richly decorated palaces.

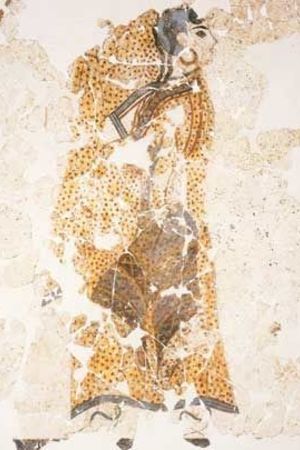

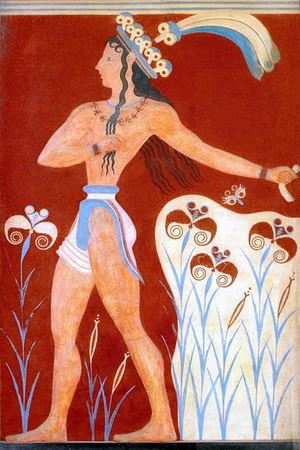

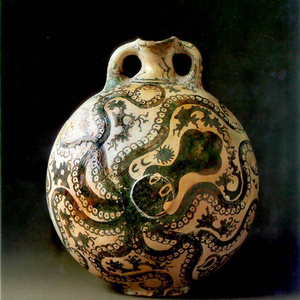

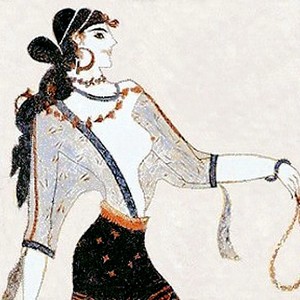

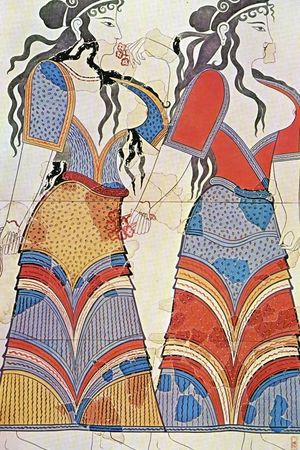

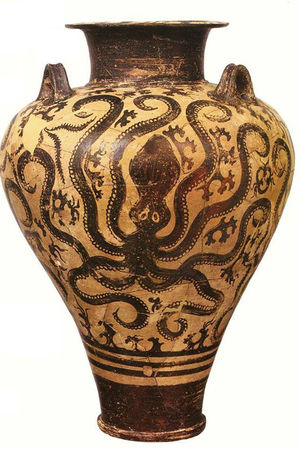

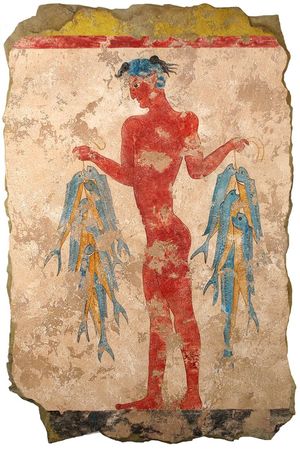

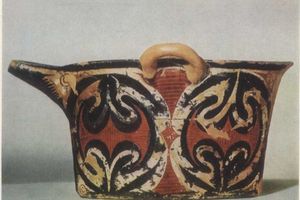

The Minoan civilization had a unique style of painting called Kamares (named after the village of Kamares, where a large number of vessels were found). This style is characterized by the strictness of forms, colorful coloring, stylized plants depicted on vessels. From the 18th century BC, Cretan art becomes more realistic. Men were depicted with a narrow waist, disproportionately developed muscles, and thinness. Another distinguishing feature can be called the depiction of eyes en face (Fr. "face to face", "opposite"), while the face itself is painted in profile. The male body was depicted in brown color, and the female one in white. Similar images can be seen in the frescoes that decorate the surviving walls. The most famous images: the earliest "Saffron Gatherer" (17-16 centuries BC), a fresco with dolphins, "Ladies in Blue", "Parisian", "Acrobats with a Bull". All the above examples of wall painting were found in the Palace of Knossos. The main theme of the images is scenes of peaceful life, festive ceremonies, processions, scenes of hunting and taming bulls.

Clothing and hairstyles

The fabrics were mostly linen and woolen, and in rarer cases, treated leather was also used to make clothing. The color palette of the clothing was quite varied: items were often dyed in red, blue, yellow, brown, green, black colors, as well as their shades. Clothing often features a floral pattern, feather decorations. Images of women that we find on frescoes, seals, dishes and decorations, show us on the one hand images of amazing refined beauty. They are dressed in clothes that vary depending on both the historical epoch and the context of the depicted scenes.

It is also worth noting the "snake goddesses" - several statuettes found in Knossos. These faience figures date back to around 1600 BC. Together with them in the same cache, half-decayed remains of clothing, belts were found. There are also several statuettes with similar iconography made of clay, bronze, and ivory.

It should be noted that most Minoan images of women are very close to the modern ideal of beauty: long hair, large eyes, thin waist, round hips, and a full chest. This is radically different from the nearest states of that time, for example, Egypt. A similar situation with clothes - it is very different from the simple, free, figure-fitting dresses of pleated white linen that we see among the inhabitants of the Nile Valley.

Minoan women wore clothes with a fairly complex cut: bell-shaped skirts with many horizontal ruffles, capes, resembling fitted sweaters, aprons, dresses cut from a single piece of cloth. Such fashion is typologically closer to Sumerian-Akkadian and Babylonian samples, known to science from images of approximately the same historical period, for example, Inanna (Ishtar) quite often appears in similar multi-layered pleated garments.

Most likely, the variant of women's dress, captured on the statuettes of the "Snake Goddesses" image, belongs to a slightly more ancient Minoan period, or is purely ritual, since we more often come across images of skirts with transverse stripes of several wedges expanding downwards, as in frescoes from Akrotiri.

The depiction of men strongly contrasts with women. They are much less in number, the skin is depicted darker than that of women, the amount of clothing is much less, and its color palette is scanty. The figures of men are slim, elongated, with wide shoulders and a thin waist. Long hair falls on the shoulders, and beards and even stubble on the face are absent. Loincloths remotely resemble the Egyptian shenti. Sometimes the loincloth is shorter at the front and falls down in the form of a wedge at the back, but on the frescoes from Knossos, models similar to skirts with an elongated front edge are also depicted. In the "Prince of Lilies" fresco, the left leg of the young man is bare, and the right one is covered at the top of the loincloth structure.

Reenactment

Currently, the reconstruction of the Cretan-Minoan civilization is complicated due to the non-preserved fabric finds, as well as the traditionally exposed breast in women's sets. It is also assumed that in reality, the shades of skin in women and men did not differ much, and the depiction of men with darker skin was of an artistic-symbolic nature.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Achaean states in the 2nd millennium BC

Literature

1. History of Ancient Greece/ Edited by V. I. Kuzishchin.Moscow: Vyssh. shk., 2003, 399 p. (in Russian)

2. Sergeev V. S. Istoriya Drevnoi Greksii [History of Ancient Greece] St. Petersburg: Poligon Publ., 2002, 801 p .

Gallery

Gallery

Fresco with dolphins of the 16th century BC Archaeological Museum of Heraklion

Fresco with dolphins of the 16th century BC Archaeological Museum of Heraklion