Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War (431–404 BCE) was a military conflict in Ancient Greece that involved the Delian League, led by Athens, on one side, and the Peloponnesian League, led by Sparta, on the other.

Long-standing tensions existed between Athens and Sparta, largely due to their differing political systems. Athens was a democracy, while Sparta was an oligarchy. In the city-states allied with them, both sides sought to establish a government similar to their own. These political differences were further exacerbated by differences in origin: the Athenians (and most of their allies) were Ionians, whereas the Spartans and their allies were mostly Dorians.

Historians traditionally divide the Peloponnesian War into two periods. During the first period ("Archidamian War"), the Spartans launched regular invasions into Attica, while Athens used its naval superiority to raid the Peloponnesian coast and suppress any signs of dissent within its empire. This period ended in 421 BCE with the signing of the Peace of Nicias. However, the treaty was soon broken by renewed skirmishes in the Peloponnese. In 415 BCE, Athens sent an expeditionary force to Sicily to attack Syracuse. The campaign ended in a crushing defeat for Athens; the expeditionary forces were completely destroyed. This led to the final phase of the war, often referred to as the Decelean or Ionian War. During this phase, Sparta, with significant support from Persia, built a substantial navy. This allowed Sparta to assist states in the Aegean Sea and Ionia that were dependent on Athens and wanted to leave the Delian League (such as Chios, Miletus, and Euboea), thereby undermining Athenian power and ultimately depriving Athens and its remaining allies of their naval supremacy. The destruction of the Athenian fleet in the naval battle of Aegospotami in 405 BCE left Athens with no chance of continuing the war, and in the following year, Athens surrendered.

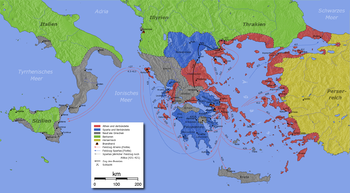

Map of the Peloponnesian War

Map of the Peloponnesian War

The Peloponnesian War is the first military conflict for which a significant number of contemporary accounts have survived. The most famous of these is Thucydides' History, which covers the period from the start of the war until 411 BCE. His work, which had a great impact on the development of historical science, largely shapes the modern understanding of the Peloponnesian War and the world in which it occurred. At the start of the war, Thucydides was an Athenian general and statesman, a political ally of Pericles. However, in 424 BCE, he was exiled for losing the strategically important city of Amphipolis, and his history was written, at least in part, during the twenty years he spent away from his native city.

Many historians continued the narrative of events from where Thucydides' History ends. The only complete surviving work is Xenophon's Hellenica, which covers the period from 411 to 362 BCE. Although valuable as the sole contemporary source for this period, Xenophon's work is justly criticized by modern researchers. Xenophon's account is not a "history" in the tradition of Thucydides, but rather memoirs intended for readers already familiar with the events. Moreover, Xenophon is highly biased and often omits information he finds unappealing; for instance, he scarcely mentions the names of Pelopidas and Epaminondas, who played a major role in the history of Greece. Historians, therefore, use his work with caution.

Other ancient works on the war were written later and have survived only in fragments. Diodorus Siculus, in his Bibliotheca historica written in the 1st century BCE, covers the entire war. His work is variably assessed by historians, but its main value lies in offering an alternative perspective to Xenophon. Some of Plutarch’s Lives are closely connected to the war; although Plutarch was primarily a biographer and moralist, modern historians draw useful information from his writings. It is important to note that these authors used both direct sources and a vast, though now lost, body of literature. In addition, modern historians use speeches, artistic works, and philosophical writings from this period as sources, many of which address the events of the war from one or several perspectives, as well as a wealth of epigraphic and numismatic evidence.

Pentecontaetia

Thucydides believed that the Spartans began the war in 431 BCE "out of fear of the growing power of the Athenians, who by then... had already subdued most of Hellas." Indeed, the fifty years of Greek history leading up to the Peloponnesian War saw the emergence of Athens as the most powerful state in the Mediterranean. After repelling the Persian invasion of Greece in 480 BCE, Athens soon became the leader of a coalition of Greek states that continued the war against the Persian Empire in Ionia and the Aegean archipelago. During this period, known as the Pentekontaetia ("fifty years," a term coined by Thucydides), Athens, initially a leading member of the Delian League, gained the status of ruler of a vast Athenian empire. Persia was forced to abandon its territories along the Aegean coast, which fell under Athenian influence. At the same time, the power of Athens grew significantly; many of its previously independent allies became dependent states required to pay tribute. These funds allowed Athens to maintain a strong fleet, and from the middle of the century, they were also used for the city’s own needs, financing large-scale construction of public buildings and the adornment of the city.

Tensions between Athens and the Peloponnesian states, including Sparta, began at the very start of the Pentekontaetia. After the Persians retreated from Greece, Sparta attempted to prevent the reconstruction of the Athenian walls that had been destroyed by the enemy (without the walls, Athens was poorly protected from land attacks and could easily fall under Spartan control); however, Athens resisted. According to Thucydides, although the Spartans took no action at that time, they "secretly... were very annoyed that they had failed to achieve their goal."

The conflict between the states flared up again in 465 BCE when a helot revolt broke out in Sparta. The Spartans asked all their allies, including the Athenians, for help in suppressing it. Athens sent troops, but upon their arrival, the Spartans declared that "their help was no longer needed" and sent the Athenians home (the other allies remained). According to Thucydides, the Spartans refused help out of fear that the Athenians might side with the rebels. In the end, the rebellious helots surrendered, but on the condition that they would be exiled rather than executed; Athens settled them in the strategically important city of Naupactus, located at the narrowest point of the Corinthian Gulf. The outcome of these events was the offended Athenians leaving the alliance with Sparta and forging an alliance with Argos, a constant rival of Sparta, and Thessaly.

In 459 BCE, Athens took advantage of a war between its neighbors—Megara and Corinth, both members of the Peloponnesian League—and signed an alliance treaty with Megara. As a result, the Athenians gained a foothold on the Isthmus of Corinth and in the Corinthian Gulf; moreover, Athenian influence in Boeotia grew. All this led to Sparta entering the war, and the so-called First Peloponnesian War began. During this conflict, Athens was forced to leave its mainland territories outside Attica (including Megara and Boeotia) under Spartan control, but the important island of Aegina remained within the Athenian alliance. The Thirty Years’ Peace, signed in the winter of 446/445 BCE, recognized both states’ right to control their own allies.

Archidamian War

The first phase of the conflict is traditionally known in historiography as the Archidamian War, named after the Spartan king Archidamus II, who commanded the combined forces of the Peloponnesian League. It is important to note that Sparta and its allies, except for Corinth, Megara, Sicyon, and Corinthian colonies, were primarily land-based states. They had the capacity to gather a substantial army, and the Spartans, as leaders of the alliance, were renowned as exceptional warriors. However, the Peloponnesian fleet was only about a third of the size of the Athenian fleet and could not compare in strength. The Peloponnesian League's war plan primarily involved invading Attica, ravaging the lands around Athens, and defeating the Athenian army in a decisive battle.

Athens, though located on the Attic Peninsula in mainland Greece, controlled vast territories primarily on the islands of the Aegean Sea. Consequently, they devised a different strategy. The main plan, proposed by Pericles, avoided a potentially losing decisive land battle. Instead, Athens intended to use its superior navy, both in size and skill, as its primary means of warfare. In the event of an enemy invasion, the rural population of Attica was to seek refuge behind the walls of Athens, abandoning their homes, while food and other supplies would be delivered to the city exclusively by sea. Athens' financial stability, largely derived from tribute paid by allies, allowed them to hope for success with this strategy.

The war began with a surprise attack by Sparta’s allies, the Thebans, on the small town of Plataea. Although Plataea was located in Boeotia, it had long been an Athenian ally. The Thebans aimed to either take control of Plataea or at least return it to the Boeotian League of cities. Secretly entering the city through walls unguarded in peacetime, a detachment of over three hundred Thebans, led by two Boeotarchs, called on the Plataeans to rejoin the Boeotian League. The invaders behaved relatively peacefully, occupying only the market square, relying on the support of local sympathizers. However, their calculation was wrong: regrouping and realizing that the Boeotians were few in number, the Plataeans attacked the enemy. In a swift night battle, some invaders were killed, some managed to escape, and the majority (180 people) were taken prisoner. The main Theban forces, arriving later, were too late and were forced to leave the city’s outskirts on the condition that the prisoners' lives would be spared. After their departure, however, the Plataeans violated the agreement and executed the prisoners.

In May 431 BCE, a sixty-thousand-strong Peloponnesian army invaded Attica, devastating the countryside around Athens. These invasions occurred annually until 427 BCE (except in 429 BCE), but each invasion lasted only about three weeks, with the longest (in 430 BCE) lasting only forty days. The reason for this was that the Peloponnesian army was essentially a civilian militia, and the soldiers had to return home in time to participate in the harvest. Additionally, the Spartans needed to keep their helots under constant control, as a prolonged absence of Sparta's main forces could lead to a helot uprising.

Map of the Peloponnesian War

Map of the Peloponnesian War

The Spartan invasion forced the Athenians, according to their initial plan, to evacuate the entire population of Attica behind the city walls. The influx of refugees led to overcrowding in the city, with many lacking even basic shelter. Meanwhile, the Athenian fleet proved its superiority over the Peloponnesian fleet, winning two battles—at Cape Rion and at Naupactus (429 BCE)—and began to raid the Peloponnesian coast.

In 430 BCE, a plague broke out in Athens, overcrowded with refugees (the symptoms, carefully described by Thucydides, seem to indicate typhus; some scholars believe it was the plague; modern molecular genetic methods have proven that the disease was caused by the typhoid fever pathogen). Between 430 and 426 BCE, the plague (with short interruptions) claimed about a quarter of the city's population (around 30,000 people). Among the victims was Pericles. The disease spread not only within Athens but also among its army. Fear of the illness was so great that even the Spartans canceled their invasion of Attica.

Significant changes also occurred in Athens' internal political life. Pericles' death led to a radicalization of their policy. The influence of Cleon, who advocated a more aggressive prosecution of the war and rejected Pericles' primarily defensive strategy, increased significantly. Cleon relied mainly on the radical-democratic elements of Athenian society, especially urban trading and artisan circles. The more moderate faction, which was based on landowners and Attic farmers and advocated for peace, was led by the wealthy landowner Nicias. As Athens' situation finally began to improve, Cleon's faction gradually gained more influence in the Assembly.

Despite serious challenges, Athens managed to withstand the severe blows of the war's first period. In 429 BCE, the rebel city of Potidaea was finally captured. The revolt on the island of Lesbos (427 BCE) also failed, with the Athenians capturing the island's main city, Mytilene. On Cleon's proposal, the Athenian Assembly even passed a decree to execute all adult males on the island and sell the women and children into slavery; however, the next day this decision was replaced by a decree to execute a thousand supporters of the oligarchy.

In 427 BCE, bloody strife broke out on Corcyra. As on Lesbos, the conflict was between local aristocrats and supporters of democracy. The victory in this civil strife went to the democrats, who destroyed their opponents; the island remained within the Athenian Empire but was significantly weakened. At the same time, in 427 BCE, after a long siege, Plataea fell to the Peloponnesians and Thebans. The surviving defenders were executed, and the city was destroyed.

From 426 BCE onward, Athens seized the initiative in the war. This was aided by a significant increase in the tribute (foros) levied from allies in 427 BCE, nearly doubling the amount. Moreover, in 427 BCE, a small Athenian squadron was sent to Sicily, where, with the help of allied cities (primarily Rhegium), it successfully conducted operations against the local Spartan allies. Under the leadership of the energetic strategist Demosthenes (not to be confused with the later Athenian orator Demosthenes), Athens achieved certain successes within Greece itself: the war was brought into Boeotia and Aetolia—at Olpae, a large Peloponnesian force of 3,000 hoplites was defeated; Nicias captured Cythera, an island south of Laconia; and a chain of strongholds was established around the Peloponnesus. In 424 BCE, Athenian forces planned to invade Boeotia from two sides, hoping for an uprising by their democratic supporters within the region.

A significant success for the Athenians during this stage of the war was the capture of the town of Pylos in western Messenia, which had a convenient harbor. This strike directly threatened the heart of the Spartan state (Pylos is about 70 kilometers from Sparta) and posed an unguarded threat to Spartan dominance over the helots. In response, Sparta took decisive action. Troops were recalled from Attica, where they were besieging Athens, a fleet was assembled, and an elite Spartan detachment was landed on the island of Sphacteria, blocking the entrance to the harbor of Pylos.

Bust of Pericles

Bust of Pericles

However, the Athenian fleet under Demosthenes defeated the Peloponnesians and cut off the garrison at Sphacteria, eventually forcing them to surrender. Among the captives were 292 Spartan hoplites, including 120 elite Spartans. The final phase of the battle was commanded by Cleon, who had been appointed by the Athenian Assembly, dissatisfied with the prolonged siege.

The blow dealt to Sparta was so severe that the Spartans proposed peace. However, Athens, anticipating an imminent final victory, refused the offer. Another factor was that Cleon, the leader of the pro-war faction, became the most influential Athenian politician after the fall of Sphacteria.

Soon, however, it became clear that Athens had underestimated the strength of the Peloponnesian League. Although the Spartans ceased ravaging Attica, the Athenians faced setbacks: an attempt to land near Corinth was repelled by the enemy, and on Sicily, an alliance of local city-states forced the Athenians to withdraw. An attempt to take Boeotia out of the war also failed: the Boeotian authorities preempted a democratic uprising, one of the two Athenian invasion armies was repulsed with losses, and the other was defeated at Delium, where the Athenian commander Hippocrates was killed. The greatest failure for the Athenians, however, awaited them in Thrace. Allied with Macedonia, the talented Spartan general Brasidas captured the city of Amphipolis, the center of Athenian holdings in the region, depriving Athens of strategically important silver mines (it was for this defeat that the historian Thucydides, son of Olorus, was exiled from Athens).

To regain Thrace, Athens sent an army led by Cleon. However, in the battle of Amphipolis, the Spartans inflicted a defeat on the Athenians, with both Cleon and Brasidas killed in the fighting.

As a result, both Sparta and Athens agreed to a peace treaty. The terms of the agreement restored the pre-war situation; both sides were to exchange prisoners and return captured cities. The treaty was named after Nicias, who led the Athenian delegation.

Dekeleian (Ionian) War

Sparta did not limit itself to sending reinforcements to Sicily. On the advice of Alcibiades, a new plan was devised to invade Attica. Instead of periodic short-term raids, the Spartans now decided to establish a permanent presence. In the spring of 413 BCE, they occupied and fortified the village of Decelea, located 18 kilometers from Athens, where a permanent Spartan garrison was stationed. This forced the Athenians to rely entirely on maritime supply routes. Additionally, access to the Laurium silver mines was cut off, further worsening Athens’ situation, and about 20,000 Athenian slaves defected to the Spartans.

Athens found itself in a very difficult position. To avoid defeat, they began building a new fleet and mobilizing all the resources of their empire.

However, the Spartans also did not waste time. After their victory in Sicily, they decided to strike in a region traditionally crucial to Athens—the Aegean Sea. In 412 BCE, Athens' strongest ally, Chios, revolted, supported by Ionian cities such as Clazomenae, Erythrae, Teos, and Miletus. Sparta sent a strong fleet to aid them, which included ships from their Sicilian allies. By 411 BCE, Ionia had completely separated from Athens. To make matters worse, Sparta sought assistance from Persia and received substantial financial support in exchange for agreeing to hand over the Ionian cities to Persian control. Alcibiades was a key figure in these negotiations with Tissaphernes, the Persian satrap of Sardis.

Athens faced the prospect of defeat. However, they were not ready to surrender and prepared to take extraordinary measures. The tribute (foros) was abolished and replaced with a 10% duty on goods passing through the straits. Athens also supported democratic factions in allied cities (for example, on Samos). The forces gathered were immediately sent to Ionia, significantly improving Athens' position in the region. Furthermore, the Spartan forces, heavily dependent on Persian funding, began to experience supply shortages, as the Persians had no interest in a complete Athenian defeat. Alcibiades’ intrigues, as he sought to switch sides back to Athens and held considerable influence with Tissaphernes, also played a role.

Significant changes occurred within Athens itself. Military failures led to increased influence of the oligarchic faction, and in 411 BCE, they staged a coup. The number of full citizens was limited to 5,000, and real power was vested in the Council of Four Hundred. A crucial element of Athenian democracy, payment for public office, was abolished. The new government offered peace to Sparta.

Attica: Athens and Dhekeleia

Attica: Athens and Dhekeleia

However, the Spartans rejected the offers. The oligarchic government was also not recognized by the Athenian fleet based on Samos. As a result, a situation of dual power emerged within the Athenian empire, which Athenian allies were quick to exploit: the wealthy island of Euboea and cities in the straits revolted (this was extremely important as most of Athens' grain was imported from the Black Sea). The Athenian fleet, now commanded by Alcibiades, who had once again sided with Athens and was granted significant authority, was tasked with suppressing these uprisings. In 411 BCE, the Athenians first forced the Spartan fleet to flee at Cynossema and shortly afterward secured a decisive victory at Abydos. In 410 BCE, they defeated the Spartans and Persians at Cyzicus, and in 408 BCE, they captured the key city of Byzantium. These military successes soon led to the fall of the oligarchic regime and the restoration of democracy. Between 410 and 406 BCE, the Athenians won victory after victory, soon managing to largely restore their former power. Alcibiades played a significant role in these victories. But the Spartans were not idle either. They sent the energetic commander Lysander to Ionia with a fleet. Lysander possessed rare diplomatic and naval talents for a Spartan and had excellent personal relations with the Persians, who stopped providing financial assistance to Athens and instead directed significant resources to him.

The Spartans' situation was eased when, after a minor defeat at Notium in 406 BCE, Athens' most capable commander—Alcibiades—was relieved of command and went into voluntary exile. In 406 BCE, the Athenian fleet, for which the last reserves of funds—gold and silver from the Parthenon—had been used, won a significant victory at the Battle of Arginusae, destroying more than 70 enemy triremes and losing 25 of their own. However, a storm made it impossible to rescue sailors from the sunken Athenian ships, and upon their return home, the victorious strategoi faced a trial.

One of the prytanes (members of the executive committee of the Council of Five Hundred) by lot was Socrates, who opposed the illegal trial as much as he could, but despite this, the strategoi were condemned and executed.

Meanwhile, the Athenian fleet was forced to resume active operations. The Spartans, under the command of Lysander, reappeared in the straits. Facing the threat of starvation and complete financial collapse (Athens now depended not only on grain supplies from the Black Sea but also on duties collected in the straits), the Athenian fleet went out to meet the Spartan fleet. However, in a state of general demoralization and declining discipline, the hastily assembled fleet was trapped by Lysander at the mouth of the small Aegospotami River, where the Athenian ships were caught at anchor and almost completely destroyed (only twelve out of 180 triremes managed to escape). Strategos Conon did not dare return to Athens and fled to Cyprus.

Athens was left without a fleet, an army, money, or any hope of salvation. After five months of siege by land and sea, the city surrendered. In April 404 BCE, a peace treaty (Theramenes' Peace) was signed. Athens lost the right to maintain a fleet (except for 12 ships), had to tear down the Long Walls, renounce all its overseas possessions, and join the Spartan alliance. These conditions were relatively lenient: Thebes and Corinth had proposed destroying the city altogether.

An additional term in the treaty was the return of exiles to Athens, most of whom were supporters of the oligarchy.

Results of the war

For a short period, an openly oligarchic regime of the "Thirty Tyrants" was established in Athens, openly supported by Sparta. The most famous of them was Critias. The "Thirty Tyrants" unleashed a reign of terror in the city, targeting both their political opponents and wealthy individuals whose assets they wished to confiscate. However, after some time (in 403 BCE), the oligarchy was overthrown, and democracy was restored in Athens.

The economic consequences of the war were felt throughout Greece; poverty became widespread in the Peloponnese, and Athens was completely devastated and never regained its pre-war prosperity. The war led to profound changes in Greek society; the conflict between democratic Athens and oligarchic Sparta, which supported friendly forces in other cities, made civil wars a frequent occurrence in the Greek world. Growing social tensions repeatedly erupted into armed confrontations.

The conflict, initially limited in scope and where both sides originally observed certain "rules," quickly escalated into an all-encompassing war, unprecedented in Greece for its brutality and scale. Violations of religious and cultural taboos, the devastation of entire regions, and the destruction of cities became widespread during the hostilities.

In the warring states themselves, the war led to significant changes in internal politics. The rise of demagogues in Athens (Cleon, Hyperbolus, Androcles, Cleophon) during the war was followed by an oligarchic tyranny upon the conclusion of peace. Sparta, although it did not change its political system, also felt the impact of the war. There was a decline in wealth among many full citizens and, conversely, an increase in wealth among some members of the polis elite. In 399 BCE, a conspiracy led by Cinadon, involving impoverished citizens who had lost their civil rights, was uncovered.

Profound changes also occurred in international relations. Athens, the most powerful polis in Greece at the start of the war, became a dependent state by its end; the Athenian empire disappeared, and Sparta became the dominant force in Greece, establishing its hegemony throughout the region. However, Sparta's brazen foreign policy, its reliance solely on force, and its lack of flexibility soon led to friction with its allies and a general rise in anti-Spartan sentiment. This culminated in the Battle of Leuctra (371 BCE), which temporarily elevated Thebes as the hegemon of Greece. The role of Persia in Greek international relations also grew significantly. Its intervention (mainly in the form of financial support, as Persia no longer dared to launch an open military invasion of Greece as in the days of Darius I and Xerxes due to its internal problems) repeatedly changed the course of the war. The Persians aimed to maintain a balance between the warring sides and ultimately weaken both.

By the middle of the 4th century BCE, no single Greek polis was left capable of dominating the others, and the polis system as the highest form of government was in decline. Consequently, in 337 BCE, Greece was conquered by the rising power of Macedonia, which united all Greek cities under its rule and began its transformation into a new superpower.

Overall, it can be said that the end of the Peloponnesian War marked the beginning of a new phase in the development of Greek society.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Athens, Sparta

Literature

- Bonnar, A. Grecheskaya tsivilizatsiya, vol. 2. Feniks Publishing House, Rostov-on-Don. - 1994-448 pp. ISBN 5-85880-082-3

- Vipper R. Y. Lectures on the history of Greece. Essays on the history of the Roman Empire (beginning). Selected works in II volumes. Volume I. Rostov-on-Don: Feniks Publishing House, 1995.

- Andreev Yu. V., Koshelenko G. A., Kuzishchin V. I., Marinovich L. P. Istoriya Drevnoi Grekii: Ucheb. [History of Ancient Greece: Textbook]. - 3rd ed., reprint. Moscow: Vyssh. shk., 2001, 399 p.: ill., maps.

- History of the Ancient World. Ancient Greece / A. N. Baidak, I. E. Voynich, N. M. Volchek et al. - Mn.: Harvest, 1998-800 with ISBN 985-433-227-6, Lurie S. Ya. History of Greece / Comp., author. вступ. articles by E. D. Frolov. St. Petersburg: St. Petersburg University Publishing House. 1993. -680 p. ISBN 5-288-00645-8

- The Peloponnesian War // Military Encyclopedia: [in 18 volumes] / ed. by V. F. Novitsky ... [et al.].-St. Petersburg.; [Moscow]: I. D. Sytin's Printing House, 1911-1915.