Pilum

Pilum (Latin: pilum, plural: pila) - a throwing spear (dart), used by the legions of Ancient Rome. The pilum was as integral a part of a roman legionnaire's arsenal as the gladius or scutum. This unusual spear was no less formidable a weapon than the legionary swords and auxiliary spears, and always, wherever the legion went, each legionnaire had one or more pilum resting on his shoulder beside his furca (a cross-shaped carrying device for personal items), waiting for its turn to offer a bloody sacrifice to Mars.

Funeral stele of Gaius Valerius Crispa, legionnaire of Legio VIII Augusta. The pilum is clearly visible. The end of the first century AD is found in Mattiakum (modern times). Wiesbaden, Germany)

Funeral stele of Gaius Valerius Crispa, legionnaire of Legio VIII Augusta. The pilum is clearly visible. The end of the first century AD is found in Mattiakum (modern times). Wiesbaden, Germany)Historical background

It is not exactly known when and under what circumstances the Romans first began to use the pilum. It is known that it was used before the 4th century BC, and according to one version, it could have been borrowed from the Samnites, Sabines, or Etruscans, who had darts for fishing that were somewhat similar to the pilum. Either way, the Roman army used the pilum, initially, apparently, arming only the velites (lightly armed and mobile warriors) and the hastati (heavily armed warriors) with it.

During the times of the reforms of the military leader Gaius Marius (157 - 86 BC), which aimed to reorganize the legions, the purpose of the scutum also changed - now it was carried by all legionnaires, and consequently, some changes were made to the battle tactics and the very structure of the pilum. Subsequently, the pilum underwent some minor changes, mostly concerning the method of attaching the tip to the shaft, changes in weight, and the softness of the metal from which the tips were made. It is believed that each legionnaire carried with him two pila, of different weights. By the decline of the Roman Empire, the pilum gradually disappears from the legionnaire's arsenal, being replaced by a lighter spiculum, if we trust Vegetius.

The combat use of the pilum

As the pilum was a throwing spear, its main purpose was to hit the enemy at a relatively short distance. In actual combat, the pilum was thrown by legionnaires at the enemy at a distance of up to 35 meters, with the aim of sowing confusion in the enemy's ranks. In addition, a direct hit by the tip of the pilum was a very formidable factor, as heavy variations of this dart could pierce armor and inflict terrible injuries, but even a pilum stuck in a shield served a certain purpose - it effectively deprived the enemy of protection, significantly weighing down his shield, not allowing it to maneuver quickly. And freeing a shield from a pilum was a very difficult task - the barbed top was tightly stuck in the shield, and the long iron tip did not allow to cut off the stuck spear. As a result - the enemy was forced to throw away his shield, remaining defenseless right before the hand-to-hand clash with the ranks of the legionnaires.

In his "Commentaries on the Gallic War," Caesar vividly described the effect produced by a volley throw of pilums at the enemy: "Since the soldiers launched their heavy spears from above, they easily broke through the enemy's formation... ...A major hindrance for the Gauls was that Roman spears sometimes pierced several shields at once with a single strike and thus nailed them together, and when the tip bent, it could not be pulled out and the warriors could not fight conveniently, as the movements of the left hand were hindered; in the end, many, after shaking their hand for a long time, preferred to throw the shield and fight, having all their body exposed".

There is also mention of the use of the pilum as a regular spear. In particular, this usage of throwing spears made a significant contribution to the victory of Gaius Julius Caesar over Gnaeus Pompey in the Battle of Pharsalus (48 BC): "Noticing that the enemy's left flank consisted of numerous cavalry, Caesar called six reserve cohorts to himself and placed them behind the tenth legion, ordering them not to show themselves to the enemy until they approached at a close distance, then to rush out of the ranks, but not to throw pilums, but to fight them as close-combat spears, effective against cavalry... ...Pompey waited to see what the cavalry would do. They were already extending the line of their squadrons to bypass Caesar and push back his scanty cavalry to the infantry. At this time Caesar gave a sign: his cavalry parted and three thousand soldiers, standing in reserve, moved towards the enemy. Fulfilling their given task, they began to strike upward with their spears and aim at the face. The cavalry, inexperienced in such battles, was terrified and could not stand the blows in the eyes. Riders, covering their faces with their hands, turned their horses and turned into a disgraceful flight."

Pilum structure

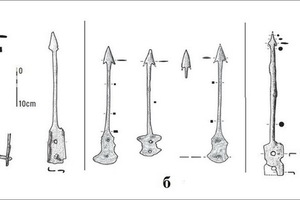

In the 3rd-2nd centuries BC, the pilum tip was usually much shorter than the later, most well-known variants. Short tips did not exceed a length of 30-40 cm, and had a wide flat shape. Already by the middle of the 2nd century AD, the pilum consisted of a long iron tip, roughly equal in length to the shaft, and had a total weight of 1 to 2.5 kg, depending on the specific model. The average overall length of the pilum was usually 2 meters, the tip was 60 cm long, although some findings reach a length of 90 cm. The bottom of the shaft often had an iron tip for sticking the pilum into the ground, if necessary.

The thickness of the tip was usually about 7 mm, and the top was serrated or pyramidal. There were several different ways of attaching the tip to the shaft, for example, the "sleeve" method - an expanding cavity was made at the end of the tip, which was put on the end of the shaft, or the most common attachment using a flat tongue, which was also attached to the shaft with several rivets, initially iron, and then wooden.

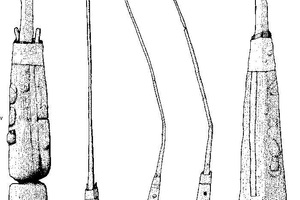

Drawing of the pilum tips. Approximately III-II centuries BC Finds from: Talamonaccio (a), Ephyra (b) and Castelrufa (c)

Drawing of the pilum tips. Approximately III-II centuries BC Finds from: Talamonaccio (a), Ephyra (b) and Castelrufa (c)The introduction of wooden rivets by Gaius Marius was caused by the need to exclude the reuse of abandoned pilums already against the Romans. As a rule, the tips of the pilums were made of rather soft materials and were not tempered, which, when hit by an enemy shield, led to a bend in the tip, and, as a result, the saw blade was unusable for reuse. However, it was noted that the tip often did not bend, so the wooden rivets served as a solution to this problem, leading to the failure of the pilum. Since the late Republic, bas-reliefs sometimes show pilums with spheres attached to them, which were supposedly made of metal, and were attached at the end of the shaft. Their purpose was, apparently, to increase the weight of the projectile, and, as a result, its penetration force.

Reenactment

First and foremost, we need to determine the tasks that will be set for the reconstructed sample of the pilum, and based on the tasks set, choose the direct type of reconstruction. In other words, for recreating the image of a legionnaire and reproducing the equipment of Roman soldiers, a pilum made "according to the combat" sample, that is, from wood and iron, is likely to be suitable. In 1998, British historian Peter Connolly recreated some samples of pilums for testing in field conditions to determine their real effectiveness on the battlefield. During the tests of penetration capacity, it was found that the early Empire model pilum could pierce an 11mm thick plywood sheet, and due to the pyramidal tip, it was difficult to extract, and the tip itself bent, in accordance with the descriptions of narrative sources.

Our club also conducted tests of the penetrating ability of this weapon, which confirmed that the pilum is an extremely formidable weapon. From a distance of several meters, the pilum was thrown at a target, which was a pig carcass, covered with a small shield. The pilum not only pierced the shield through, but also the "enemy" hiding behind it, causing him life-incompatible wounds.

List of literature

Bishop, M.C.; Coulston, J.C.N. (2009). Roman Military Equipment from the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Oxford Books;

Connolly, Peter. "The pilum from Marius to Nero: a reconsideration of its development and function", Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies, vol. 12/13

Zhmodikov, Alexander, 2000, "Roman Republican Heavy Infantrymen in Battle (IV-II Centuries B.C.)," in Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, vol. 49 no. 1.

JAMES CURLE, F.S.A. SCOT., F.S.A. A Roman frontier post and it's people. The fort of Newstead in the Parish of Melrose. Glasgow, MDCCCCXI. Originally published by JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS for the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

Related topics

Gallery

Gallery

Pilum tips from Castrum in Martin Hill 370-380 AD Slovenia. Stored in the National Museum of Slovenia

Pilum tips from Castrum in Martin Hill 370-380 AD Slovenia. Stored in the National Museum of Slovenia