Gladius

Gladius or gladius (Latin: gladius) is a Roman short sword designed for thrusting attacks.

There is a version that the Romans adopted the gladius as their main close combat weapon from the inhabitants of the Iberian Peninsula (presumably the Celts), modifying it to suit their own tactics of warfare. This type of sword was called Gladius Hispaniensis (Latin for "Spanish sword"). The word "gladius" itself is likely derived from the Celtic word "kladyos" ("sword"), although some historians believe that this term may also come from the Latin "clades" ("injury, wound") or "gladii" ("stem").

The stabbing form and short length of the gladius were determined by the inability to effectively deliver slashing strikes in a dense legionary formation. Outside of a tight infantry formation, the gladius was inferior to Celtic swords in many aspects. It was used by the Romans as the main type of weapon among infantry until the 3rd century, after which it was replaced by the spatha, which served as an intermediate option between the gladius and the long barbarian swords. This change was influenced by broader processes taking place in the Roman Empire, such as "barbarization" and changes in the military tactics of infantry. As a result, the spatha became the main sword of the Great Migrations period and transformed into the swords of the Vendel and Carolingian types.

Gladii were mainly used by representatives of the Roman army: legions, auxilia, and gladiators.

Development history

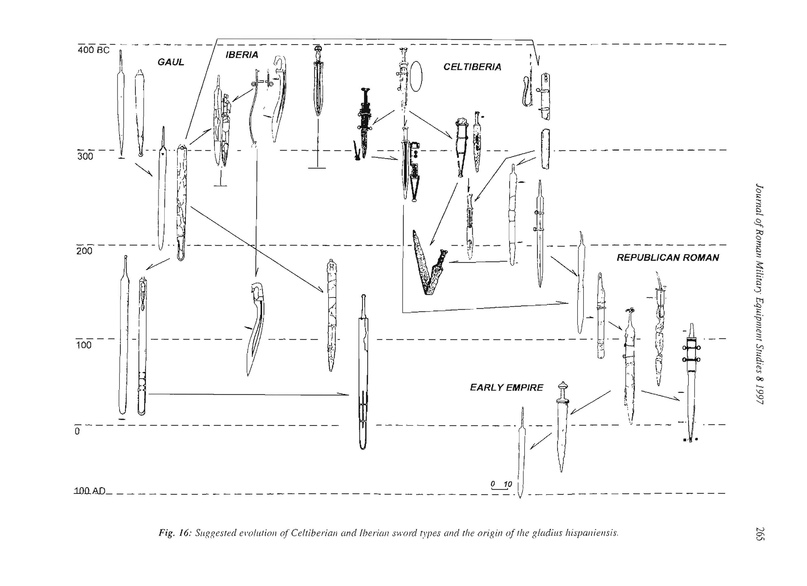

It is believed that the gladius was adopted by the Romans after the Battle of Cannae (216 BC). It is most likely that before gladiuses, the Romans used a variant of the Greek xiphos. The main version of the origin of the gladius is considered to be the adoption of the design from the Celtiberians, its shape speaks in favor of this theory.

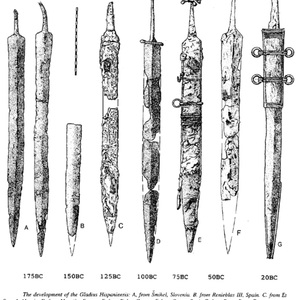

Scheme with the development of ancient swords

Scheme with the development of ancient swords

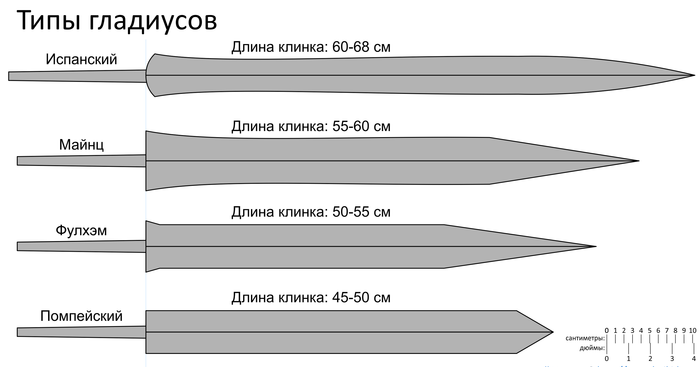

Initially, the gladius was a fairly long sword. Its earliest type, widespread in the Republic, was called "Spanish". With the development of both the Roman army itself and the adaptation of the gladius to legionary combat techniques, its size began to decrease. The length of the blade of the largest "Spaniards" was 65 cm, and the shortest and later "Pompeii" - up to 45 cm.

From the second quarter of the 2nd century AD, swords with Sarmatian hilts (famous for their ring-shaped pommel) spread as an alternative to Pompeian-type gladiuses, and in the third quarter of the century they were joined spats like "Lavriak-Gromovka". By the beginning of the 3rd century, the spata was becoming the main sword of the Roman army. It should also be noted that the gladius did not completely disappear from the everyday life of the Romans, so it continued to be used in gladiatorial fights according to graphic sources of 3-4 centuries.

Types of gladius

Over a long period of time, the gladius did not remain unchanged; it was constantly modified in certain ways. Today, several types of ancient Roman swords are distinguished:

Gladius"Spanish" :

The earliest type of this weapon and the most common among finds. It has an overall length of about 75-85 cm, a blade length of 60-65 cm, a blade width of 5 cm, and a weight of about 900-1000 g. The blade has a characteristic leaf-shaped form with a curve. Period of use: 216 BCE - 20 BCE. The heaviest and longest gladius.

Gladius Mainz :

A sword with an elongated point and a slight waist of the blade; it has an overall length of about 65-70 cm, a blade length of 50-55 cm, a blade width of 7 cm, and a weight of about 800 g. This type of gladius is named after its first discovery in the vicinity of the German city of Mainz. Period of use: 13 BCE - early 2nd century CE.

Fulham Gladius :

Similar to the "Mainz" type, the main difference being a triangular point and a narrower blade. It has an overall length of about 65-70 cm, a blade length of 50-55 cm, a blade width of 6 cm, and a weight of about 700 g. The first specimens were found in Fulham, Great Britain. In terms of blade shape, it is an intermediate variant between the "Mainz" and "Pompeii" types. Often, this type of gladius is not considered separate and is considered a variation of the "Mainz" type. Period of use: 43 CE - 100 CE.

Gladius "Pompeii" :

A blade with parallel edges and a triangular point, very similar to another type of Roman sword called the spatha, but shorter in length. It has an overall length of about 60-65 cm, a blade length of 45-50 cm, a blade width of

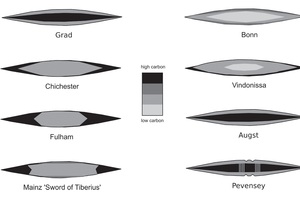

Typology of Roman gladiuses

Typology of Roman gladiuses

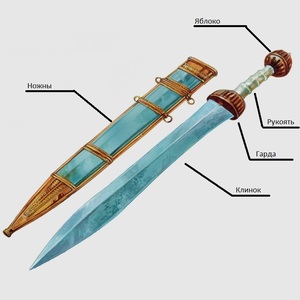

Device

The components of a gladius can be distinguished as follows:

- Blade

- Hilt

- Pommel

- Guard

- Scabbard

Functional purpose of gladius elements - it is obvious and doesn't have any difficulties in understanding. Nevertheless, let's go through its construction.

The function of the guard, like in any other sword, is partial protection for the wrist, reinforcement of the sword's structure, and also a support for thrusting strikes against the opponent (which was the main technique), allowing the gladius to be quickly withdrawn for a repeated strike. The handle, of course, was used for gripping the sword.

It was assumed that the main function of the pommel was to shift the center of gravity towards the handle by means of an enlarged spherical top (counterbalance). This is commonly believed, however, the surviving pommels were made of wood or bone - relatively lightweight materials - and were not capable of significantly changing the position of the center of gravity. If such a task was indeed intended, the pommel should have been made of metal, for example. However, archaeological finds do not confirm this. So, most likely, the main function was to provide a firm grip on the gladius to prevent the hand from slipping down during a strike.

The blade of the gladius had a relatively wide cutting edge at the tip to enhance its thrusting capability. It was used for fighting in formation. While it was possible to slash with the gladius, cutting strikes were considered preliminary. It was believed that the opponent could only be killed with a strong thrusting strike, for which the gladius was designed.

Scabbard - an integral attribute of any gladius. It was used for storage and quick drawing of the sword in close formation, which is why legionaries wore it on the right shoulder. The scabbard was attached to the belt through stitched straps threaded through rings on the scabbard. Sometimes buckles were placed on the straps for easier putting on and taking off of the scabbard.

Gladii were mostly made of iron, but there are also mentions of bronze swords. As shown by the surviving examples of Roman swords, from the end of the 2nd century AD and especially in the 3rd century AD, gladii were already made of forged steel. The gladius was popular among the legionaries - the heavy infantry of Rome. The velites (light infantry of the Romans) used gladii only as auxiliary weapons. In the hands of skilled warriors, this sword delivered fast and deadly strikes, but its length allowed for close-quarters combat with the enemy. The most experienced legionaries were able to fence with it as skillfully as they could chop, cut, or thrust.

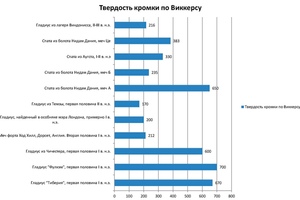

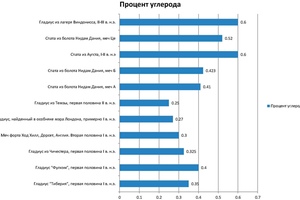

We will also analyze the material from which gladiuses were made. We will focus on metallography and metal quality research. Let us remind you that iron and steel are not synonymous, and they are different materials in their properties. One of the quality indicators of an alloy is the percentage of carbon content, the higher it is, the greater the strength and hardness, but the lower the ductility and viscosity. The percentage of carbon in Roman steel ranges from 0.02 % to 2.14 %. On the one hand, the greater the hardness, the better, because it is this characteristic that determines the ability of the sword to penetrate into another environment. The problem is that when the hardness increases, the brittleness of the metal also increases, and a sword that cracks in the heat of battle can cost its owner his life.

Modern metallographic studies of Roman swords suggest how this problem was solved. The sword was made of two parts with different carbon content, the Romans wrapped steel plates with a higher carbon content around the soft core, as a result, the cutting edge had high hardness, and the center was plastic and did not allow the blade to break.

Modern state standards categorize steel grades according to the percentage of carbon and the content of alloying elements. Alan Williams singled out the maximum hardness of the sword as a quality criterion (as a rule, this is an indicator of the cutting edge). Of course, it is impossible to draw unambiguous conclusions from a relatively small sample of the study, especially since we do not have a complete picture of the slag content, cutting edge thickness, etc. for all swords. Nevertheless, these studies allow us to calculate the most likely technologies for making swords, which the Roman masters tried to adhere to. The percentage of carbon varied widely, usually 0.1-0.4 in the core and up to 0.7 % at the edge. These are fairly common values – the average carbon content of most swords from Antiquity to Modern times was found in these ranges. By modern standards, the closest analogue will be medium-carbon steels used in the production of structures or vehicle parts. The edge hardness ranged widely from 170 to 700 VPH. It can also be noted that by the end of the 2nd century, patterned welding became widespread.

Not only could the carbon distribution in the blade vary, but the shape of the blade itself could also vary. In a cross-section, the blade most often represented a convex lens with a thickening towards the center, which played the role of a stiffener. But there were also other options - for example, rhombic, or even concave lenticular borders. It is assumed that the inward-concave borders appeared not as a result of the production of gladiuses, but during their operation. Over time, the blade blunted and required sharpening, which drained the edges of the blade.

By the end of the blade's edge, the gladius was thinning out. At the same time, the stiffening edge was often preserved, which could lead to the shape of the tip not only as a point or longitudinal, but also as a cross.

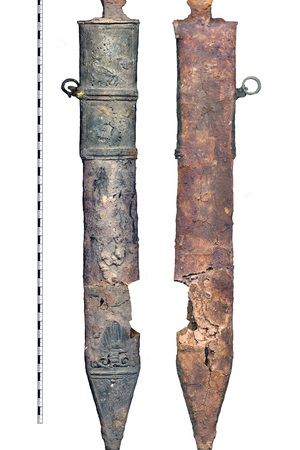

It should also be noted that not only the gladius scabbard could be decorated, but the blade itself could have decorative modifications. As an example, let's take a closer look at the discovery made by amateur archaeologist Wolfgang Joche. Gladius was found in 1971-1972 in landfills in Wiesbaden, left over from excavations of the Roman settlement in Mainz. (H. Schoppa, Ein Gladius vom Typus Pompeji, Germania 52, 1974, pp. 102-108.).

Gladius is a type of "Pompeii", has a pewter-bronze scabbard. An iron spearhead was also found with it. A gladius with a parallel double-edged blade of complex design, flattened diamond-shaped cross-section with ribs at the tip and a long shank is dated to 70-90 AD. On the base of the blade there are embossed inscriptions on both sides:

"C. Valer(i) Pr[imi]/C.Valeri(i) Pri(mi)"

"C. Valeri(i) P[rimi] C. Raniu(s)/C. Vale[ri] Primi"

Total length with mount: 63.6 cm (25 inches).

The scabbard consists of bronze elements with remnants of a tin coating and is decorated with an engraving. The upper part of the scabbard shows a helmeted warrior walking to the right, but with his head turned back. He holds a spear and shield, is clad in a muscular carapace and a high crested helmet. A shield stands at his feet. The lower part shows a winged Victoria. End cap (scabbard tip) It is also decorated with the image of a winged Victoria holding a palm branch, and above it is a separate palmetto pattern with curls.

Scabbard length: 14.5 cm (5.75 in).

Gladius of Wiesbaden. General view of the find. 70-90 AD

Gladius of Wiesbaden. General view of the find. 70-90 AD

Use in combat

The design of the gladius allows us to consider it primarily a piercing weapon. But this is not enough for an unambiguous answer to the question "is Gladius a stabbing weapon or a chopping one?". In this regard, we will analyze the main sources for its use in combat conditions, relying primarily on legionnaires. In addition to the regular army, gladius was also actively used. gladiators where it was actively used, including as a chopping weapon. But this is more likely due to the peculiarities of the gladiator fights themselves, rather than the evolution of weapons in the Roman army.

Let's cite other written sources in which gladius can be considered both piercing and chopping hand-to-hand weapons.

Polybius noted in his characterization of gladius:

- "The gladius is equipped with a strong, strong blade, and therefore it stabs perfectly and cuts both sides effectively." Further describing the superiority of the legionnaires over the phalangites, he also notes that "the Romans, when fighting alone, require freedom of movement, when the warrior covers his body with a shield, turning each time in the direction from which the blow threatens, when he fights with a sword that cuts and stabs"

Dionysius of Halicarnassus, along with stabbing blows, also describes specific chopping blows.:

- "And those who [the Romans] saw these parts of the body protected, they cut the tendons under the knees or on the ankles and threw them [the barbarians] to the ground-gnashing their teeth, biting their shields and uttering a cry like a roar, like wild animals."

We will also mention the description of the injuries inflicted by gladius, which Livy gives us:

- "Hitherto they [the Macedonians] had seen only wounds from spears or arrows, occasionally from pikes, and they were accustomed to fight only with the Greeks and Illyrians; now, seeing corpses mutilated by Spanish swords, hands cut off with a single blow along with the shoulder, severed heads, spilled out intestines and much more, Just as terrible and disgusting, Philip's warriors were horrified by the kind of people, the kind of weapons they would have to deal with."

Separately, I would like to mention written sources about the choice of a place to kill the enemy.

- Polybius, General History, II, 33, 6 : "Striking the enemy in the chest and face, and striking blow after blow, the Romans, thanks to the foresight of the tribunes, put most of the enemy's army on the spot."

- Plutarch, Caesar 16: 4 : "Cassius Sceva, who in the battle of Dyrrachia, having lost an eye knocked out by an arrow, was wounded in the shoulder and thigh by javelins, and received the blows of one hundred and thirty arrows with his shield, called out to the enemies as if to surrender; but when two of them came up to him, he cut off the arm of one with his sword, another was put to flight by a blow to the face, and he was saved by his own men, who came to the rescue. "

- Tacitus, Annals, II, 14, 4 : "It is necessary to increase the speed of blows, pointing the point of weapons in the face: the Germans have no shells, no helmets"

- Tacitus, On the life and character of Julius Agricola, 36 : "So the Batavians began to strike the Britons with their swords, smite them with the bulges of their shields, stab them in the uncovered faces, and, crushing those who stood on the plain, they went up the hill fighting, and the rest of the cohorts, competing with them and fighting with them. supported by their onslaught — they cut down all who met them; and in their haste to complete the victory, our men left behind them lightly wounded and even unharmed enemies."

- Plutarch, Caesar 44, 11-12 : "With these words, he [Centurion Gaius Crassinius] was the first to rush at the enemy, dragging a hundred and twenty of his soldiers with him; cutting down the first enemies he met and forcing his way forward with force, he laid many of them down, until at last he himself was struck down by a sword blow in the mouth, so that the blade went through and came out through the back of the head."

In addition to the description, traces of the use of gladius in battle have also come down to us.

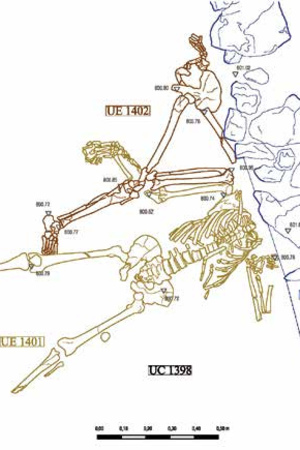

Remains of an Iberian settlement have been found near the village of Almunilla (Córdoba province). The findings of 2006-2009 shed light on the events of the II century BC. e. Archaeologists found very characteristic traces of fire. Usually people try to fight the fire or later try to restore housing in this place, but not here. No one tried to save the village of Cerro de la Cruz, the fire destroyed buildings for several days. In addition, archaeologists found skeletons of two men, indicating a violent death.

One of them, aged 21-25 years (height 168 cm), had an injury to his right shoulder blade-it was severed by a single strong gladius blow. There's also a notch in his sciatic bone – he's clearly been hit from behind by a sword. The second man was older (30-35 years old) he was about 167 cm tall and was a relative of the young man. His left leg was cut open with a single blow (the fibula was severed). In addition, his right arm was cut off near the shoulder, and there are also traces of a blow on the thigh.

There are other skeletons, but they are much worse preserved. It is difficult to say what exactly happened here in antiquity, most likely, these are the events of the Lusitanian War (155 BC -139 BC) and the consequences of the campaigns of Quintus Fabius Maximus Servilianus.

Other examples of gladius were found in the study of the remains of soldiers who died in the Sertorian War in Valencia (75 BC). Apparently, the favorite business of Roman legionaries was cutting off limbs with one blow. One of the warriors had both arms and legs chopped off. One soldier had both his arms cut off, as well as his head, and they threw it at his feet, or rather where they should have been, because they were also cut off.

You can't ignore visual sources either. As a rule, in them we can observe either the moment of a stabbing blow, or the moments of readiness for a stabbing blow from a defensive stance.

In summary, the gladius was more of a stabbing weapon. But this does not mean that it could not be used for chopping blows. On the contrary, many sources speak of its versatility, so that despite the fact that the gladius is primarily a stabbing weapon, it could also be used effectively for chopping blows, depending on the tactical situation on the battlefield.

Reconstruction

This type of weapon is ideal for legionaries, praetorians, and auxiliaries. It is also the primary weapon for more advanced-ranking warriors, such as optios or centurions. However, for higher-ranking officers, such as legates, it would be more appropriate to use a parrus. It should also be noted that gladius is not suitable for cavalry soldiers - they used longer weapons, such as spathae. Apart from the Roman army, gladius is also well-suited for reconstructing gladiators. For safety reasons, blunting the weapon's edge and tip is permitted during reconstruction.

Related topics

Legionnaire, Pugio, Cingulum, Spatha, Centurion, Gladiators

Literature

- Flavius Vegetius Renatus (1996). Vegetius: Epitome of Military Science (in Spanish). Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-08-532391-0-9.

- Livius, Titus. "The History of Rome, Vol. II". 7.10. Archived from the original on August 30, 2002. Retrieved 25 November 2010.

- Nicodemi, Walter; Mapelli, Carlo; Venturini, Roberto; Riva, Riccardo (2005). "Metallurgical Investigations on Two Sword Blades of 7th and 3rd Century B.C. Found in Central Italy". ISIJ International. 45 (9): 1358–1367. doi:10.2355/isijinternational.45.1358

Gallery

Gallery

Gallery

Gallery

Mainz gladius with a partially silvered bronze scabbard, which still has claws and upper trim. The find is 66.5 cm long and dates back to AD 50, Nijmegen Museum.

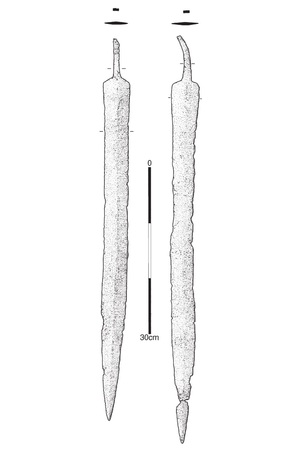

Mainz gladius with a partially silvered bronze scabbard, which still has claws and upper trim. The find is 66.5 cm long and dates back to AD 50, Nijmegen Museum. Gladius type "Mainz". It was found in the River Rhine. Also called the sword of Tiberius. The British Museum in London. First half of the first century

Gladius type "Mainz". It was found in the River Rhine. Also called the sword of Tiberius. The British Museum in London. First half of the first century Gladius 72.3 cm long, in a scabbard 58.6 cm long; with a partially preserved decorative tin coating. Dated between 30 BC and 30 AD, Museum Ljubljana.

Gladius 72.3 cm long, in a scabbard 58.6 cm long; with a partially preserved decorative tin coating. Dated between 30 BC and 30 AD, Museum Ljubljana.  Gladius, dating from 60-30 BC, which retains part of the wooden structure of the scabbard and the metal structure. The length of the sword is 69 cm, the scabbard is 65 cm.

Gladius, dating from 60-30 BC, which retains part of the wooden structure of the scabbard and the metal structure. The length of the sword is 69 cm, the scabbard is 65 cm. Gladius and cingulum. Second half of the 1st century AD, Catalog of finds of the Croatian part of the Danube Limes

Gladius and cingulum. Second half of the 1st century AD, Catalog of finds of the Croatian part of the Danube Limes A Pompeii-type gladius from Colonia Ulpia Traiana (present-day Xanten), late 1st century AD, is preserved in the Xanten Regional Museum, inv. number 80, 16861. The Mix catalog number is A800

A Pompeii-type gladius from Colonia Ulpia Traiana (present-day Xanten), late 1st century AD, is preserved in the Xanten Regional Museum, inv. number 80, 16861. The Mix catalog number is A800

Gallery-Klinki

Gallery-Klinki

Gladius of the Mainz type from one of the monuments of the Bay of Naples, possibly Pompeii (Italy), 79 AD.

Gladius of the Mainz type from one of the monuments of the Bay of Naples, possibly Pompeii (Italy), 79 AD. Mainz-type gladius with silver handle, 1st century AD, Museum Speyer, previously exhibited in the Palatinate.

Mainz-type gladius with silver handle, 1st century AD, Museum Speyer, previously exhibited in the Palatinate. Spanish gladius dated between the 2nd century BC and the first half of the 1st century BC; Total length 71.1 cm (blade 58 cm, minimum-maximum blade width 37-44 mm, weight 405 g)

Spanish gladius dated between the 2nd century BC and the first half of the 1st century BC; Total length 71.1 cm (blade 58 cm, minimum-maximum blade width 37-44 mm, weight 405 g) This gladius dates from the middle of the first century BC and has a length of 58 cm (blade 44 cm, minimum-maximum width of the blade 31-35 mm); Part of the elegant bone handle with a female figure carved on it has been preserved. Found at the site of the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, it is in a private collection.

This gladius dates from the middle of the first century BC and has a length of 58 cm (blade 44 cm, minimum-maximum width of the blade 31-35 mm); Part of the elegant bone handle with a female figure carved on it has been preserved. Found at the site of the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC, it is in a private collection. Gladius, which has preserved the skeleton of the handle, with an iron plate on the guard, a semi-dome in the upper part of the pommel and three small intermediate disks; Total length 58.3 cm (blade 42.8 cm, minimum-maximum blade width 42-66 mm, weight 407 g). It dates from the end of the 1st century BC and the middle of the 1st century AD.

Gladius, which has preserved the skeleton of the handle, with an iron plate on the guard, a semi-dome in the upper part of the pommel and three small intermediate disks; Total length 58.3 cm (blade 42.8 cm, minimum-maximum blade width 42-66 mm, weight 407 g). It dates from the end of the 1st century BC and the middle of the 1st century AD.

Gallery-Scabbard

Gallery-Scabbard

Scabbard decoration, 1st century AD, Currently on display at the Carnuntinum Museum (Austria, Bad Deutsch-Altenburg), private collection, Published: Exhibition catalog "Legionsadler und Druidenstab, F. Humer, 2006," ISBN 3854602294 "

Scabbard decoration, 1st century AD, Currently on display at the Carnuntinum Museum (Austria, Bad Deutsch-Altenburg), private collection, Published: Exhibition catalog "Legionsadler und Druidenstab, F. Humer, 2006," ISBN 3854602294 "

Gallery-Handles

Gallery-Handles

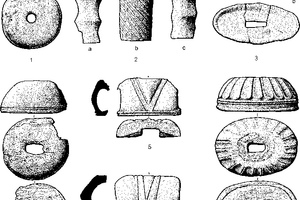

Gladius pommels from the Republic to the early Empire. On the left are the handles from the Spanish type, and on the right are the Pompeian ones.

Gladius pommels from the Republic to the early Empire. On the left are the handles from the Spanish type, and on the right are the Pompeian ones.

Visual sources

Visual sources