Praetorians

The Imperial Guard, or the Praetorians (Latin: praetoriani), were the personal bodyguards of the emperors of the Roman Empire. Their origin traces back to an elite unit (ablecti) of allies who served as protectors of the commander-in-chief and his praetorium during the Republic period. This is where the name cohors praetoria or cohortes praetoriae originated. Scipio Africanus also organized a guard of Roman horsemen under the same name. The headquarters, office, and entire close entourage of the general or provincial governor formed his cohors praetoria.

The Praetorians existed from 27 BCE until 312 CE, when they were disbanded by Emperor Constantine the Great.

History of the Praetorian Guard

The Praetorian Guard of the Roman emperors officially formed under the first Roman emperor, Augustus, in 27 BCE.

Before Augustus, during the Roman Republic, the term "praetorians" referred to an elite unit consisting of both infantry and cavalry that protected the commander and his headquarters. Hence the name cohors praetoria, and in other sources cohortes praetoriae. This unit included younger relatives, clients, and freedmen of the commander.

In addition to protecting the commander, they formed his honorary retinue.

Often, young noble aristocrats joined this unit, aspiring to gain military experience, make useful connections, and build a career.

The creation of the "praetorian cohort" is attributed by Roman historians to Scipio Aemilianus, the conqueror of Carthage (2nd century BCE).

In the 1st century BCE, Roman generals began to surround themselves with bodyguard units, which did not necessarily consist solely of elite Roman soldiers.

Before the civil wars of the 40-30s BCE, the term "praetorians" referred to the bodyguard units of officials, particularly governors.

During the civil wars in Rome in the 1st century BCE (40-30s BCE), starting with the wars of Caesar and Pompey and ending with the war between Octavian and Mark Antony, the composition and role of the praetorian cohorts changed somewhat. They were now recruited from elite soldiers and tasked with protecting the general on and off the battlefield. If necessary, they could be deployed as a tactical reserve during battle.

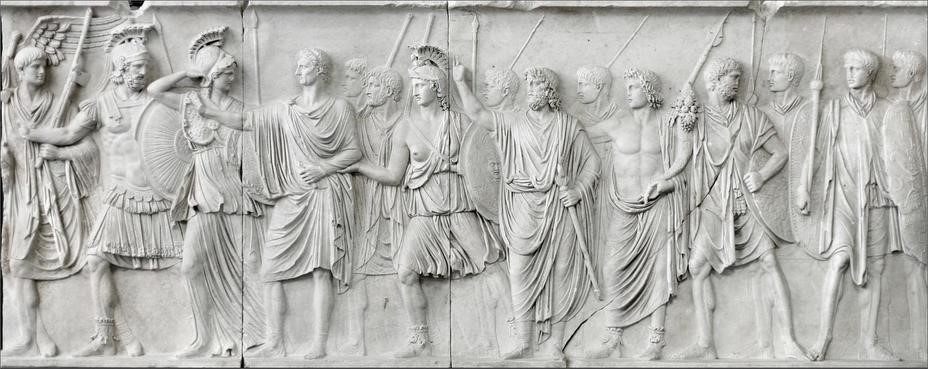

Marble relief from the Palace of the Conservators in Rome (Palazzo Cancelleria) depicting the triumph of Domitian. Luna marble. Rome, Vatican Museums, Gregorian Profane Museum. 81-96 AD.

Marble relief from the Palace of the Conservators in Rome (Palazzo Cancelleria) depicting the triumph of Domitian. Luna marble. Rome, Vatican Museums, Gregorian Profane Museum. 81-96 AD.

Numbers and history of the Praetorians

Starting with the first Roman emperor Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE), the Praetorians became a permanent part of the Roman army. Under him, the Praetorian cohorts consisted of 9 cohorts, numbering 4,500 soldiers. Augustus kept three cohorts in Rome itself, while the other six were stationed in the nearby cities of Latium. The Praetorians were commanded by two senior officers bearing the title praefectus praetorio. They were appointed from the equestrian class, for whom this was the pinnacle of their career. Sometimes there was only one, as with Sejanus under Tiberius, or three, as under Emperor Commodus. Due to their proximity to the emperor, the praefectus praetorio became part of the emperor’s council, gradually acquiring administrative and judicial powers. The praefectus praetorio held supreme command during large-scale military operations and, in the absence of the emperor, ruled Italy and Rome.

In 23 CE, according to Tacitus, the Praetorian Guard consisted of 9 cohorts. During the reign of Caligula or Claudius, their number increased to twelve. In 69 CE, Vitellius disbanded the old guard of Emperor Otho and recruited 16 new cohorts, each with 1,000 soldiers. Vespasian restored the Praetorian Guard from Otho’s guards, some of Vitellius’s guards, and his distinguished soldiers to the form it had under Augustus, reducing the number of cohorts to nine. During the reign of Domitian or Trajan, a tenth cohort was created, and the number of cohorts remained unchanged until the reign of Septimius Severus.

The question of the number of soldiers in a cohort remains open, as literary and epigraphic sources do not provide complete clarity. Dio Cassius believed that one cohort had 1,000 soldiers, but according to archaeological data, at least in the time of Augustus, the size of one cohort was 500 men—supported by the area of the Praetorian camp and the three urban cohorts on the Viminal Hill.

Septimius Severus replaced the old Praetorian Guard with distinguished soldiers from across the empire.

The Guard demonstrated its corruption during the Crisis of the Third Century, the era of soldier-emperors. The emperor Diocletian, who came to power in 284 CE, reformed the Praetorian Guard.

Under the tetrarchy system, the guards were distributed among four emperors who ruled different parts of the empire. A small detachment of Praetorians remained in Castra Praetoria.

The Praetorians fought their last battle at the Milvian Bridge on October 28, 312. In this battle, two claimants to the throne of the Western Roman Empire—Constantine and Maxentius—clashed. Despite fierce resistance from Maxentius's Praetorians, he lost. The victorious Constantine disbanded the Praetorian Guard. Former soldiers of the Praetorian cohorts were assigned to border units on the Rhine and Danube. By order of Emperor Constantine, only the southern and western walls of Castra Praetoria in Rome were destroyed, as the northern and eastern walls had by then become part of the Roman city walls. The destruction of the fortress showed that the era of the Praetorians had ended. Starting with Constantine the Great, the Praetorians were replaced by the scholae palatinae. This unit included 500 cavalrymen who protected the emperor during campaigns and did not possess sufficient power to influence imperial politics.

Praetorians, relief from the now-lost triumphal arch of Emperor Claudius. Louvre, Paris. 1st century AD.

Praetorians, relief from the now-lost triumphal arch of Emperor Claudius. Louvre, Paris. 1st century AD.

Organization and Composition of the Praetorians

The Praetorian cohort was a mixed unit composed of infantry and cavalry. Each cohort consisted of 6 centuries of foot soldiers, each numbering between 60 and 80 men, led by a centurion. Additionally, the cohort included 3 cavalry turmae, each with 30 horsemen. These cavalrymen were nominally listed within the cohorts to which they were assigned, but they also formed a special corps of 900 men under the command of a special optio (optio equitum). In peacetime, they served as messengers and couriers. An ordinary soldier could become a cavalryman after five years of service.

Another elite unit within the Praetorian cavalry was made up of 300 men, known as "scouts" (speculatores)—the most loyal soldiers who were tasked with serving directly under the emperor. This unit was also led by a special centurion, who held the title of "trecenarius" (commander of three hundred). The second most senior centurion held the title of "camp commander" (princeps castrorum). Unlike in the legions, the remaining centurions of the guard had equal status and equal pay.

The number of soldiers in the guard gradually increased, primarily due to the expansion of the number of centuries and turmae within each cohort. During the last two decades of the 1st century and most of the 2nd century, the number of centuries per cohort gradually increased from six to ten, and the number of turmae from three to five. Thus, the strength of each cohort rose from 500 to nearly 1,000 warriors. While under Augustus the Praetorian Guard numbered 4,500 men, under Vespasian it grew to 7,200, Domitian increased it to 8,000, under Commodus it reached 10,000, and Septimius Severus raised it to 15,000 men.

Praetorian in segmentata armor. Column of Antoninus Pius. Second half of the 2nd century AD.

Praetorian in segmentata armor. Column of Antoninus Pius. Second half of the 2nd century AD.

Duties and Functions of the Praetorians

During the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD) in 23 AD, all the Praetorian cohorts were moved to Rome, and a common camp was built for them in the northern part of the city, between the Viminal and Esquiline hills.

The Praetorians guarded the imperial palace complex on the Palatine, accompanied the emperor on the streets of Rome when he participated in various ceremonial or religious events, and the entire guard marched out of Rome when the emperor took command of the army to undertake a military campaign or conquer another province. Inscriptions indicate that Praetorian detachments were also involved in fighting the bandits plaguing Italy.

Salary and Privileges of the Praetorians

As elite troops, the Praetorians had special privileges, particularly regarding their salary. A Praetorian's annual pay was 750 denarii under Emperor Augustus (27 BC–14 AD), compared to 225 denarii for an ordinary legionary per year. Under Emperor Domitian (81–96 AD), the salaries of both legionaries and Praetorians were increased: to 300 denarii for a legionary and 900 denarii for a Praetorian. A Praetorian's pay exceeded that of a regular legionary by 2 1/3 times.

In addition to their regular pay, Praetorians received various bonuses from the emperors on special occasions: 1) ascension to the throne (each emperor paid the Praetorians a sum five times their usual salary upon ascending the throne; Emperor Claudius, for instance, ordered 3,750 denarii to be given to each Praetorian upon his accession); 2) major military victories; 3) family celebrations in the imperial family (the birth of an heir, marriage, adoption, etc.); 4) the ruler's jubilees; 5) the emperor's will (according to his will, Augustus ordered that each Praetorian be paid 2,500 denarii upon his death in 14 AD).

Praetorians served not for 25 years, as other soldiers in the empire did, but for 16 years. After 16 years, they could retire or receive an officer's post in the auxiliary troops on the frontier. During their service, Praetorian soldiers could climb the career ladder, with corresponding increases in salary. After four years of service in the guard, they could be promoted to "scouts" in the cavalry and later rise to the rank of junior commanders (principals)—such as tesserarius, optio, vexillarius, and so on.

Praetorians who advanced to senior principal positions easily obtained centurion rank in the army or in one of the Roman urban cohorts, retiring honorably after 16 years of service and then enlisting for extended service as an evocatus. If they remained in the army as centurions, Praetorians strove to achieve the rank of primus pilus centurion. If they stayed as centurions in the urban cohorts, after several years of service, they often sought to transfer back to the guard as centurions of the Praetorian cohorts.

Sestertius of Nero, minted between 64 and 67 AD in Lugdunum, Gaul. ADLOCVT COH signifies the emperor addressing the Praetorian cohorts.

Sestertius of Nero, minted between 64 and 67 AD in Lugdunum, Gaul. ADLOCVT COH signifies the emperor addressing the Praetorian cohorts.

Recruitment into the Guard

Initially, Praetorians were recruited from Italy and the Romanized provinces of Macedonia, Spain, and Noricum. A recommendation letter or the patronage of an influential nobleman was the main factor that could help a young aristocrat enter the guard. Distinguished soldiers could also be transferred to the guard from the legions.

The proportion of provincials in the Roman guard gradually increased, reaching half of the total by the end of the 2nd century. Finally, in 193 AD, Septimius Severus disbanded the old guard and began recruiting it from distinguished soldiers of the provincial legions. Dio Cassius, in his "Roman History," described Severus's decision to replace the old guard with soldiers from the legions: "He did this thinking that he would gain a guard more familiar with military duties and would provide a kind of reward to those who showed bravery in war. In reality, however, he undoubtedly ruined the Italian youth, who instead of former military service turned to banditry and gladiatorial games, while the city was filled with a motley crowd of soldiers of the most savage appearance, complete country bumpkins in speech and manners...".

During the era of the "soldier emperors" (the crisis of the 3rd century), the Praetorian cohorts began to take the names of the emperors, which were quickly discarded when power changed hands. Thus, the 2nd cohort was briefly called "Gordian's" in honor of one of the Gordians. The 5th cohort at one time bore the title "Philip's" in honor of Emperor Philip the Arab.

Surviving wall of the Castra Praetoria. Rome, Italy.

Surviving wall of the Castra Praetoria. Rome, Italy.

Equipment of the Praetorians

According to Trajan's Column, the armor and weapons of the Praetorians were similar to those of the legionaries, with the distinction that they were more luxurious and expensive.

Their weapons included the gladius, pilum, and pugio. There is debate about their helmets: some say they wore the imperial type legionary helmet, while others suggest they used a helmet with a movable brow guard and a large crested plume (feathers). Segmentata armor was the most common, although many depictions show muscle cuirasses, likely worn by officers of the guard.

It is worth noting the somewhat archaic nature of the Praetorians' equipment. For shields, they mostly used the Republican version of the oval scutum. The exterior of the shield was decorated with images of Jupiter's winged lightning bolts, crescents, and stars. Additionally, there is an image of a Praetorian from the time of Nero dressed like a hoplite—with a linothorax, hasta, and hoplon. However, this was probably an exception due to the emperor's whim, rather than a consistent pattern in their equipment.

Warrior on a fresco from Pompeii. 80–20 BC.

Warrior on a fresco from Pompeii. 80–20 BC.

When guarding the imperial palace on the Palatine, in the theater, circus, or Colosseum, the Praetorians were dressed in civilian clothing, including the toga, under which they concealed a sword. Mounted Praetorians wore hamata or lorica squamata and special flat hexagonal shields with the image of a scorpion (a symbol of the Praetorian Guard introduced under Emperor Octavian Augustus) and Jupiter's winged lightning bolts.

Both "Attic" helmets and special cavalry helmets (engraved with human hair motifs and with cheek guards fully covering the ears) were used. Their weapons included the spatha, used to strike enemies from horseback, as well as spears, and they often carried throwing darts attached to the saddle in a special quiver.

The equipment of a foot Praetorian in the 1st-2nd century AD could consist of the following elements:

Textile/Leather items:

Protective equipment items based on metal:

Weapons items:

Additional elements:

Praetorian Standards

Unlike the standards of the legions (signa), the Praetorian signa were adorned with images of the winged goddess of victory, Victoria (Nike to the Greeks), a scorpion, and the emperor and his family members. In the legions, there was also the position of imagifer, who carried the standard with the emperor's image.

The guards' trumpeters and standard-bearers wore lion skins over their helmets, while in the legions, standard-bearers and trumpeters used wolf and bear skins. A legion's aquilifer, for special merits, could wear a lion skin, as in the guard.

Praetorians and Politics

The Praetorians and their commanders—the Praetorian prefects—often played a significant role in the politics of the Roman Empire. There were times when the Emperor of Rome was chosen by the Praetorians (for example, the ascension of Emperor Claudius, who became emperor by the will of the guards who killed Emperor Caligula in 41 AD). Many Roman emperors were killed by the Praetorians or directly by the Praetorian prefect. For example, the tribune of the Praetorian Guard, Chaerea, personally killed Emperor Caligula in 41 AD. The Roman Emperor Commodus was assassinated in 193 AD with the involvement of the Praetorian prefect, after which the Praetorians started a series of emperor successions for money, leading to the Year of the Five Emperors. Due to this discreditation, the victorious Septimius Severus in 193 AD ordered the old guard to be disbanded and replaced with a new one from distinguished legionary soldiers. The Praetorian prefect Macrinus organized a plot to assassinate Emperor Caracalla (of the Severan dynasty) and subsequently became Roman Emperor from 217 to 218 AD. Officers of the Praetorian Guard killed Emperor Aurelian in 275 AD. Sometimes, the Praetorian prefects concentrated power in their hands, nearly equal to that of the emperor. An example is the Praetorian prefect Sejanus (commander of the guard from 15-31 AD) under Emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD). However, Tiberius eventually realized his mistake and executed Sejanus in 31 AD. The history and political aspirations of the Praetorians ended in the 4th century when Emperor Constantine I the Great (306-337 AD) finally disbanded them in 312 AD and destroyed their camp in Rome.

Related topics

Legionary, Sub-helmet, Paenula, Sagum, Focale, Subarmalis, Tunic, Braccae, Subligaculum, Caligae, Calceus, Socks, Galea, Segmentata, Squamate, Hamata , Lorica Musculata, Cingulum, Gladius , Pugio , Scutum

Literature

1. Herodian. History of imperial power after Mark

2. Bedoyere G. de la. Praetorian: Rise and Fall of Rome’s Imperal Bodyguard

3. Tacitus. Annals

4. Tacitus. History

5. Schiller, «Die Röm. Staats-, Rechts- und Kriegsaltertümer».

6. The Roman Army // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

7. Cohort // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

8. Praetorians / / Encyclopedia of Pomegranates: In 58 volumes, Moscow, 1910-1948.

9. Semenov V. V. Praetorian cohorts: model and practice / / Para bellum: journal. St. Petersburg, 2001, No. 12, ISSN 1683-8114.

10. Cohors / / Real dictionary of classical antiquities / author-comp. F. Lubker; Edited by members of the Society of Classical Philology and Pedagogy F. Gelbke, L. Georgievsky, F. Zelinsky, V. Kansky, M. Kutorgi and P. Nikitin. - St. Petersburg, 1885.

11. Rankov, Boris. The Praetorian Guard. — Osprey Publishing, 1994. — 64 p. — ISBN 9781855323612.

12. Durry M. Les cohortes pretoriennes. — Paris, 1938.

13. Passerini A. Le coorti pretorienni. — Roma, 1939.

14. Rankov B. The Praetorian Guard. — Osprey Publishing, 1994.

15. Ushakov Yu. A. The role of the Praetorian Guard in the internal political life of the Roman Empire under the first emperors// Antique Civil Community, Moscow, 1984, pp. 115-131.

16. Semenov V. V. Praetorian cohorts: model i praktika [Praetorian cohorts: model and practice]. Para bellum, St. Petersburg, 2001, no. 12.

Gallery

Gallery