Calcei

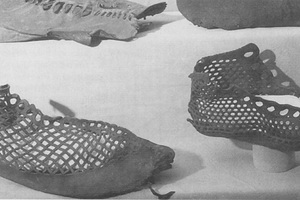

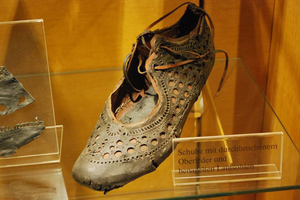

Calcei were closed Roman or Greek footwear made of tanned leather. They consisted of a sole to which the upper part was sewn, completely covering the foot. Socks were often worn under calcei for comfort and warmth, especially in the northern provinces. Sometimes the upper part of the calcei had decorative cutouts. The sole of the footwear was often studded with nails for stability when walking in non-urban areas.

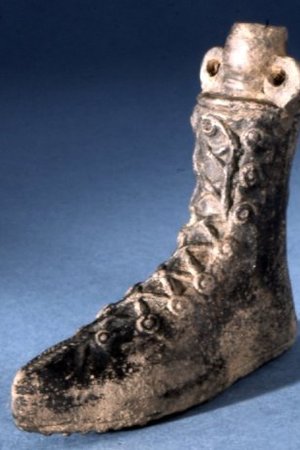

The ancestors of calcei first appeared on the Italian Peninsula among the Etruscans - it was leather footwear with a pointed toe. There is an opinion that this type of footwear could have been influenced by the Near East. An example of calcei can be found on a sarcophagus from Cherveteri, dating back to the end of the 6th century BCE.

Over time, the pointed toe went out of fashion, but calcei themselves continued to be used for centuries. This type of footwear was used by the masses in antiquity, particularly in ancient Rome: senators, high-ranking officers, soldiers, emperors, women, children, and so on. It should be noted that the mentioned individuals could also have other types of footwear, such as sandals and caligae.

Calcei for the military

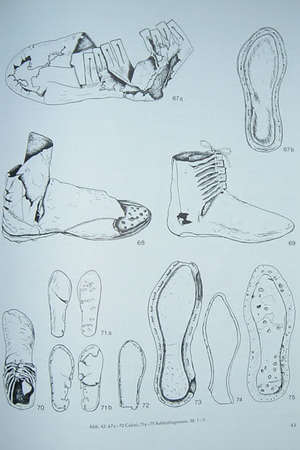

The calcei of legionaries and auxiliaries differed from senatorial and legate calcei in their simplicity and practicality. As one of the main characteristics of a legion was the ability to undertake long marches on foot, footwear played a vital role in this matter. Poor footwear could lead to reduced mobility during battle and injuries even before the onset of the battle. Therefore, calcei were the most demanding detail in terms of personal equipment fitting. For example, officers, such as centurions, were often depicted wearing calcei-type footwear rather than caligae. Additionally, based on the places of discovery, calcei were found throughout the territory of the Roman state. Generally, closed footwear was more common in the north.

Examples of calcei can be observed on Trajan's Column and Marcus Aurelius' Column.

Calceae can be seen on the sagitarium (left) and auxilarium (right) of Trajan's Column, 2nd century AD, Rome.

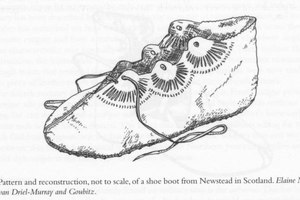

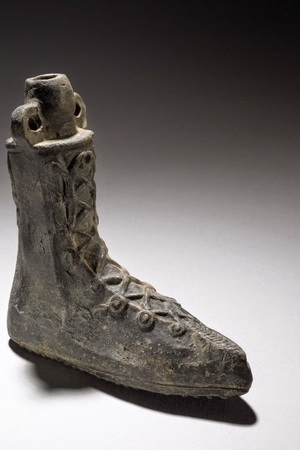

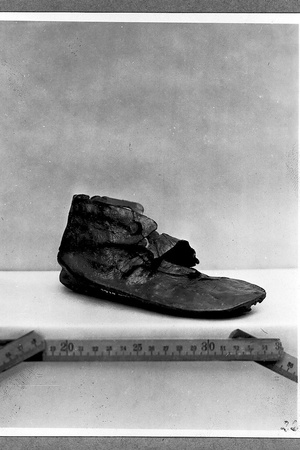

Calceae can be seen on the sagitarium (left) and auxilarium (right) of Trajan's Column, 2nd century AD, Rome.The calcei differed not only in the length of lace holes, their appearance, decorative embellishments, or color but also in their height. There are images that closely resemble modern "sneakers," supported by archaeological sources. An example is a men's calceus from the Roman fort at Bar Hill, dating back to 142-180 CE. Its sole size measured 28 cm.

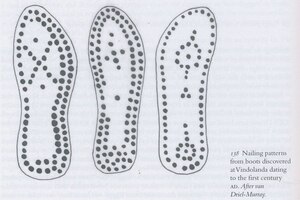

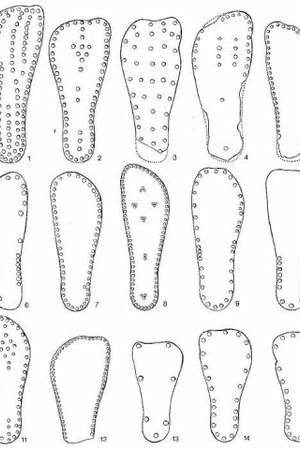

A significant element of military calcei is the studding of the sole with nails for improved walking comfort and stability. However, it cannot be said for certain whether this was a mandatory or distinctive feature of military footwear. It is quite possible that studding was also used in civilian footwear. It should also be noted that the studding could be done in various patterns, some of which can be found in the article about caligae.

Calcei among the noble class

The widespread use of calcei does not mean that they were all the same. Calcei varied in the quality and color of the leather used, as well as in the pattern, design, and lacing. There is a hypothesis that Caesar wore bright red calcei during his triumphal procession (Cassius, Roman History 43.432). Perhaps he used color as a means of distinguishing social classes. For example, the black calcei of equestrians appear similar in position to the footwear of senators and patricians, but dyeing the footwear black was relatively cheaper.

The calcei of patricians and senators differed from each other in the quality of leather and craftsmanship. By the time of Diocletian's Edict, patricians' calcei were sold for 150 denarii, while the cost of senators' calcei was 100 denarii. There are no literary or artistic testimonies that specifically indicate how the boots of equestrians and senators differed, but the edict (9.7–9) lists equestrian calcei at a significantly lower price of 70 denarii per pair. The calcei depicted on the statue of the orator Aulus Metellus strongly resemble the later footwear of senators and patricians.

From the late Republic to the middle of the Empire, the appearance of calcei remained virtually unchanged, with only minor variations. Calcei were worn through a slit at the top, allowing the boot to be opened wide for putting it on. Four leather straps crisscrossed around the foot and ankle, tying in front of the ankle with two knots. Such calcei can be observed on the Ara Pacis.

On the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, double-knotted calcei can be observed. Looking at them, one can speculate that the calcei had a double sole, between which two long leather strips were threaded, wrapping around the foot. It can also be noticed that the toes were covered with a soft layer of calceus leather.

At the Norwegian Institute in Rome, there is a statue of an empress wearing calcei, dating back to the 3rd or 4th century CE. Researchers interpret the round relief decorations around the lace holes as pearls. The rich decoration of the footwear and cloak indicates that only an empress could dress in such a manner.

Calcei for women

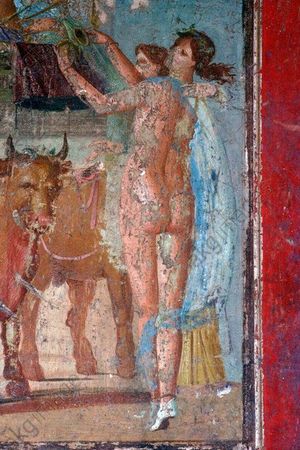

Calcei for women may not have had significant differences from men's or children's footwear. This is well demonstrated by the finds from Bar Hill, where not only men's calcei but also presumably women's and children's calcei have been discovered. All three shoe specimens have a low height and are richly decorated with cut-out patterns. In images, women's feet were often covered by clothing, which often makes their identification difficult in pictorial sources.

There is an opinion that respectable and pious women in Ancient Rome were expected to wear closed-toe footwear. Open-toe footwear could indicate excessive looseness in a woman. However, there are Roman depictions of noble women wearing open-toe footwear, particularly sandals. A significant portion of Roman depictions were influenced by Greek styles, sometimes directly copying Greek statues while only changing the head, and in Greece, open-toe footwear was much more prevalent. There are enough depictions of women of different status wearing both open-toe and closed-toe footwear, so it cannot be definitively stated that closed-toe footwear had a class-specific significance.

Reenactment

Calcei are best suited for reconstructing the appearance of Roman citizens and Roman officers, such as senators, priests, and centurions. In the case of legates and emperors, calcei are also suitable, but they acquire a less practical yet more pompous appearance. Women could also wear calcei, and they are applicable for reconstructing female attire accordingly. The main challenge in reconstruction lies in selecting the appropriate sources for the desired portrayal, as they share many structural elements. To determine whether the footwear is military or not, one can consider the place of discovery (if it's a Roman fort, then it is most likely auxilia/legionary footwear). Anatomical features can also help determine the intended wearer (if the footwear is small, it is likely children's footwear), as well as the type of lacing and the presence of nails on the sole. Examples of calcei reconstructions from the 1st to 2nd centuries CE are presented below.

Calcey Reconstruction

Calcey Reconstruction

Related topics

Caligae, Sandals, Legion, Legionnaire, Augur, Tunic, Toga, Socks

Literature

Goldman, N., in Sebesta, Judith Lynn, and Bonfante, Larissa, editors, The World of Roman Costume: Wisconsin Studies in Classics, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1994

Military footwear

Military footwear

Other footwear

Other footwear