Sandals

Sandals (Greek σανδάλιον, Latin sandalium) are a type of simple open footwear with a sole and no heels, secured to the foot with leather straps or ropes.

The concept of wearing sandals is far from new. Footwear resembling sandals has been found among many peoples. It is believed that sandals appeared in Rome due to the influence of Greece or the Etruscans. However, it is more likely that sandals emerged in Rome independently. It should also be noted that this type of footwear was known among other Mediterranean peoples, independently appearing outside the Italian peninsula, particularly in Ancient Greece and Egypt.

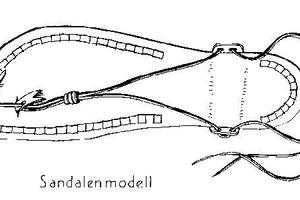

A popular type of sandal in the ancient Mediterranean is similar to what is commonly sold today: a sole with a fastening that separates the big toe from the other toes, along with straps crossing the foot from above and secured on the sides of the sole. The sole was usually made of leather, sometimes wood. In the case of leather soles, they were often multi-layered, with the layers held together by small leather straps or nails. Sandals could feature various decorations on the straps or the sole.

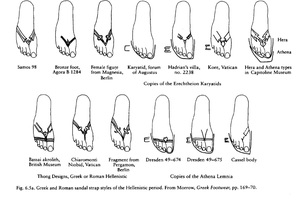

Morrow drew various types of sandals, many of which also appear on Roman statues and mosaics from all periods of Roman art.

Each civilization around the Mediterranean basin created sandals from materials available at hand. There are Etruscan sandals dating to the 7th century BC with a two-part wooden sole, covered in leather and a metal rim, found in a tomb in Bisenzio, now housed in the Villa Giulia Museum in Rome. Leather straps (no longer preserved) connected the two parts, and a bronze frame held the contoured sole together.

These thick-soled sandals were popular throughout Etruscan times, as fragments have been found in early tombs and depicted on later monuments. The Etruscan style was even copied in Athens, the "fashion capital" of those times.

Roman frescoes, mosaics, and sculptures depict numerous types of sandals common in Italy throughout the Republic and Empire periods.

For instance, in the initiation room at the Villa of the Mysteries in Pompeii, frescoes show women wearing simple soft sandals with thin soles, similar to those worn by street musicians depicted in a mosaic from Cicero’s house. Also, elegant sandals can be seen on the foot of Apollo in the Central Hall of the Naples Museum.

In Ancient Rome, the style of sandals was often borrowed from the Greeks but not universally. Roman sandals were characterized by wide straps crossing the wearer's foot and secured to the sole on the sides. This style of sandals has Greek roots but was adapted to Roman fashion.

Morrow states that, according to literary sources, Roman sandals were similar to Greek trochades. The types of sandals in Rome were diverse. There were the so-called "Gallic" sandals, the simplest wooden sandals, likely worn by agricultural workers or builders. They were valued at about eighty denarii per pair with a double sole and fifty denarii per pair with a single sole. Morrow notes in her glossary that the name trochades (diminutive, trochadia) comes from the Greek verb trecbo, "to run," implying their use by runners.

Another type of sandal was taurina, usually made from bull hide. These were worn by women and valued at fifty denarii per pair with a double sole and thirty denarii per pair with a single sole. Taurinas could be gilded, then valued at seventy-five denarii and lanatae.

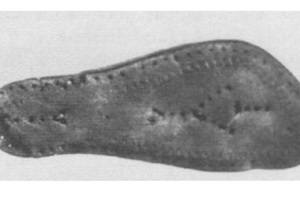

In the Netherlands, Germany (Saalburg, Bonn Berg, Mainz, and Cologne), and England (along the Thames Embankment in London and at Vindolanda, a Roman fort on Stangate Road south of the Roman wall), hundreds of sandal soles have been found, as well as some entire sandals, with remnants of soles up to three to seven layers of leather thick. Many soles feature various nail patterns.

Carol van Driel-Murray's classification traces the changes in sandal styles from the 1st to the 3rd century AD. In the first century, sandal soles were the same shape for everyone—men, women, and children. Then, in the first quarter of the second century, distinct male and female styles emerged. Women's sandals became narrower with a more pointed toe, while men's sandals became rougher and wider. In the third century, a strange enlargement of the toes of men's sandals appeared. Smaller-sized sandal soles also had wide toes, indicating that children, probably boys, wore such unusually styled sandals. This style did not spread further in the fourth century.

Van Driel-Murray suggests that this style likely reflects the power of the militaristic society and the privileged position of soldiers, showing the influence of militarism on civilian clothing in the provinces.

Sandal soles are also of interest. Some soles have the initials of the maker or his mark, or simply decorative patterns on the inner sole.

Excavations in England in buildings in Billingsgate in 1974 and at New Fresh Wharf (St. Magnus House) in 1985 in London reveal the same interesting progression in sandal fashion noted by van Driel-Murray on the continent. Sandals are often more than just a type of footwear. Roman marble, bronze, or terracotta lamps were sometimes made in the shape of feet shod in sandals.

Sandals in the form of a pair of glass bottles are an exhibit in the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne. This is transparent glass with colored straps; when filled, they take on the color of the contents.

Indoors, sandals were worn by nobles and slaves. However, their quality differed. People of lower status likely wore sandals outdoors as well.

Literary evidence suggests that only citizens of high status were allowed to wear a special type of closed Roman shoe called Calcei Patricii or senatorii. Such restrictions likely did not apply to simple calcei in the northern provinces, where the climate was much harsher. Archaeological finds also indicate the presence of closed footwear for both citizens and non-citizens.

Sandals were removed when the wearer reclined on a couch at a banquet. Asking for sandals (poscere soleas) was considered a declaration to the banquet host of an intention to leave.

Related topics

Literature

- Goldman, N., in Sebesta, Judith Lynn, and Bonfante, Larissa, editors, The World of Roman Costume: Wisconsin Studies in Classics, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1994

Gallery

Gallery