Linothorax

Linothorax (Ancient Greek: λινοθώραξ) is an ancient Greek cuirass made of linen fabric. It was also known in other parts of the ancient world. Similar armor was probably used from the Mycenaean period. From the end of the 6th century BC, they become the standard protective gear of hoplites and were most common among Greek city-states. Compared to bronze armor (thoraxes), linothoraxes were lighter, cheaper, and less restrictive, while providing a comparable degree of protection. Linothoraxes were actively used until the 3rd century BC, after which they were displaced by other types of armor from mass use. There is evidence of later use in the Roman Empire, but this is more of an exception.

Unfortunately, no linothoraxes have been found, but there is a large number of pictorial and written sources.

Linothorax among the Macedonians

On a mosaic from Pompeii, Alexander the Great is depicted in a linothorax, with presumably metal shoulder guards and a breastplate, with a band of scales around the waist. Presumably, such protection was typical for the cavalry of the Hetairoi.

According to late Macedonian inscriptions from Amphipolis, containing the military statute of Philip V, the linothorax (under the name cotthybos) was the standard cuirass of ordinary phalangites. At the same time, it is likely that commanders and warriors of the first phalanx line used metal thoraxes or hemithoraxes (thorax, hemithoraks). For the loss of a cotthybos, a soldier had to pay a fine twice less than for a thorax/hemithorax, which gives information about the price ratio of these two types of armor. Probably, in the times of Philip II and Alexander, Macedonian soldiers were equipped in a similar way.

Presumably, the linothorax was the standard armor of the Macedonian army. In the description of the Macedonians' campaign in India, it is mentioned that by Alexander's order, the army was equipped with 25,000 new cuirasses. At the same time, he ordered to "burn" the "old and worn out" ones.

The main pictorial evidence that Alexander the Great wore a linothorax is the famous Pompeii mosaic, where the Macedonian king is depicted in a linen armor. In addition, the ancient Greek philosopher Plutarch wrote in the biography of Alexander the Great that the commander was dressed in a linothorax during the Battle of Gaugamela: "Having ordered to pass this to Parmenion, Alexander put on a helmet. All other armor he put on still in the tent: a Sicilian work hypendima with a belt, and over it a double linen cuirass, taken from the loot captured at Issus" (XXXII). In this battle, which took place on October 1, 331 BC, the Greeks won, which led to the death of the Persian Empire.

Linothorax among the Etruscans

The Etruscans also used linothoraxes in their army, sometimes reinforcing them with metal plates. A similar cuirass with narrow, vertically oriented plates in the Assyrian style can be seen on the statue of Mars from Todi, located in the Vatican's Gregorian Etruscan Museum. Images of linothoraxes reinforced with metal plates date back to the 3rd century BC, when the Etruscans also introduced chainmail, which they borrowed from the Celts, modifying it with rectangular shoulder reinforcements that were fixed on the chest. Later, this form was borrowed by the Celts themselves, after which it passed into the Roman army.

Linothorax among the Romans

In the Roman army, linothoraxes were not used as massively as in Greece, however, there are mentions in pictorial sources about this. The most famous are the bas-relief with the centurion and the fresco with the praetorian, dressed in linothoraxes. The latter, the most recent evidence of the use of linothorax in the ancient world, dates back to the era of the early Roman Empire.

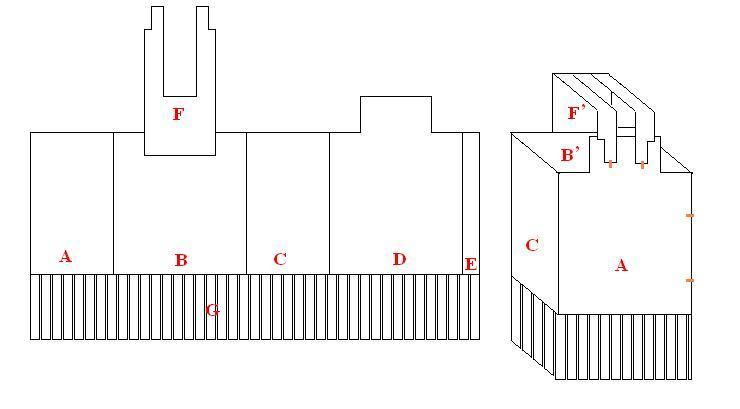

Construction

The linothorax was made from several layers of linen fabric, which were treated with a special solution and tightly glued together. Essentially, this makes the linothorax the first composite armor. The total thickness was about 0.5 cm. The main part of the cuirass was something like a wide band with cutouts in the armhole area, which was wrapped around the body and fastened on the left side (A, B, C, D, and E in the diagram above). The lower part of this main detail was cut in the form of ribbons (the so-called pteruges, the name of which was transferred to denote the ends in the roman subarmalis. They are marked with the letter G in the diagram), which covered the upper part of the thighs, without hindering the movement of the legs. Another layer of fabric was attached from the inside, the pteruges of which were located opposite the cuts of the pteruges of the outer layer. On the figure of a warrior, the pteruges formed a kind of segmented skirt. Sometimes this part could be removed from the linothorax. At the back at the top, a P-shaped detail was attached, the ends of which were thrown over the shoulders and fixed on the chest (marked with the letter F in the diagram). Due to their elasticity, the shoulder pads straightened and took a vertical position in the unfastened state. Sometimes the linothorax could additionally be covered with metal plates or scales. It is assumed that the weight of such armor was from 3.5 to 5 kg.

Diagram of the linothorax structure

Diagram of the linothorax structure

Related topics

Hoplite, Lorica Musculata, Lorica lintea, Centurion, Praetorian

Literature

Connolly, Peter. Greece and Rome. Encyclopedia of Military History = Greece and Rome at War. - Moscow: EKSMO-Press, 2001. - 320 p. - ISBN 5-04-005183-2.

Secunda N., McBride A. The Army of Alexander the Great. - AST, 2004. - 56 p. - ISBN 5-17-022244-0.

Gallery

Gallery