Gladiator

Gladiator (Lat. gladiator - "sword-bearer," from gladius - "sword") was a fighter in ancient Rome who battled similar individuals for the entertainment of the public in special arenas. Despite the name, gladiators could include not only warriors who used swords but also spearfighters, trident wielders, and so on.

The main reason for the emergence of gladiatorial games is believed by historians to be the adoption of a funerary ritual from the Etruscans. Both slaves and free people who fought with swords near a grave could be potential victims of human sacrifices. The strongest survived, while the weak perished, and this ceremony thrilled those present. Perhaps it was the love for this ritual that led to the development of gladiatorial games.

There is also another version of their origin, based on frescoes from Campania depicting a religious and ritual custom, as well as mentions of such games by Titus Livius. According to this version, it was customary in ancient times to kill captive enemies over the grave of a deceased noble warrior, offering them as sacrifices to the gods of the underworld. Subsequently, these cruel sacrifices likely transformed into ritual battles between warriors wielding gladii (swords). The first gladiators were called "bustuarii" (from "bustum" - a funeral pyre on which the body of the deceased was burned). This demonstrates the initial connection of gladiatorial games (munera) with funeral ceremonies, in honor of which the earliest recorded Roman spectacles were organized in 264 BC. They were held in conjunction with the funerals of Lucius Junius Brutus. Over time, gladiatorial games began to be organized for other occasions as well, such as religious festivals.

Many slaves voluntarily sought to join gladiator schools as it was a way for them to earn their freedom. In the gladiator school, novices faced rigorous training, and many could not cope with the heavy demands. Gladiators who performed well in the arena were awarded a wooden sword called "rudis" and ceased to be slaves, gaining their freedom. Many of these gladiators did not leave the arena but continued to fight as free men. It brought them money, fame, and the adrenaline rush that many craved.

In 105 BC, gladiatorial games were included among public spectacles. From then on, the state took control of this aspect of society's activities and entrusted its magistrates with the organization of the games. Gladiatorial games became the most beloved spectacle in the entire Roman state. This characteristic was often exploited by politicians who sought to rise to public office, as they could gain support from the people. In 65 BC, Julius Caesar organized games involving 320 pairs of gladiators. Such grand gestures greatly intimidated his political opponents. Lavish games became a reliable way to quickly gain the favor of the people and secure votes in elections. In 63 BC, Cicero proposed a law prohibiting candidates for magistracy from organizing gladiatorial games within two years before the elections due to Caesar's actions. However, no one could prevent a private individual from organizing such games under the pretext of commemorating a relative, especially if the deceased had bequeathed the organization of the games to their heir, which served as a formal way to bypass the prohibition.

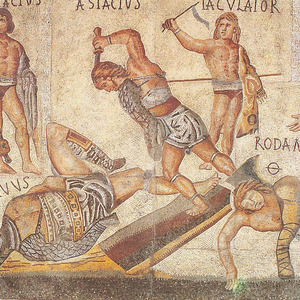

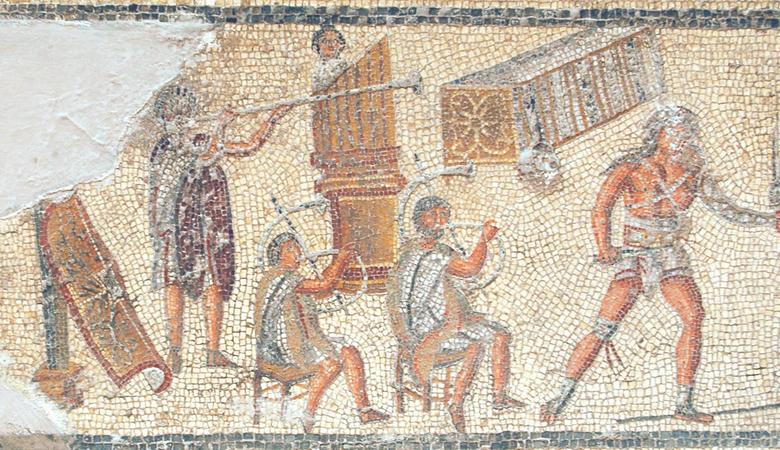

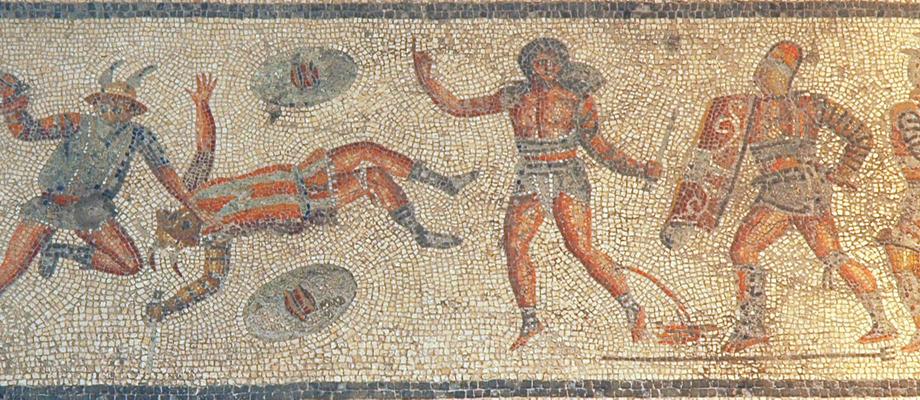

Zliten mosaic from Libya (Leptis Magna). 2nd century AD

Zliten mosaic from Libya (Leptis Magna). 2nd century AD

Classification of gladiators

The most common types of gladiators:

- Bestiarius (Latin for "beast fighter"). Fought against animals in the arena. The name derives from the Latin word "bestia," which means "beast" or "animal." The earliest bestiarii were poorly armed or unarmed. Initially, execution of criminals sentenced to death was carried out through their exposure to wild animals. Later, bestiarii underwent special training in bestiarii schools (scholae bestiarum or bestiariorum), equipped themselves, and fought for money.

- Dimachaerus (Latin for "dual-sword fighter"). The name dimachaerus literally means "with two swords" (from Greek Διμάχαιρος). Dimachaeri wore helmets, short greaves, and lorica hamatas. They could be armed with various cold weapons such as sickles, gladii, or pugio.

- Equit (Latin for "horseman"). Fought on horseback, armed with a lance, a sword, and a parma shield. The main characteristic of equites was that, unlike most other gladiators who fought topless, they wore tunics overlaid with a classic gladiator belt called balteus. In combat, equites usually threw their spears first, then dismounted and continued the fight. They usually fought against other equites.

- Hoplomachus (Latin for "spear-fighter"). Equipped with a spear and a shield. Their gear imitated the appearance of Greek hoplites, representing their image in the arena. The equipment consisted of a helmet adorned with feathers, a hybrid shield, and a hoplon made from a single thick bronze sheet, tall greaves, and manica. The hoplomachus used the hoplon as their main weapon and a pugio as a secondary weapon. They often fought against murmillos or other sword-wielding gladiators.

- Murmillo (Latin for "fish"). Equipped with a gladius (sword) measuring 40-50 cm in length and a slightly smaller version of the scutum (shield). Murmillones wore a type III gladiator helmet with wide protective visors all around and a crest. Sometimes the crest and temples of the helmet were adorned with feathers. They also wore a manica, greaves, subligaculum, and balteus. The weight of their equipment ranged from 12 to 18 kg. Murmillones' main opponents were the Thraex and Retiarius, as depicted in visual and written sources. They also occasionally fought against hoplomachi and provocatores.

- Provocator (Latin for "challenger"). They were depicted wearing a loincloth, a belt, a short greave on the left leg, a manica, and a helmet with a visor, without visors or crest. They were armed with a gladius and a shield similar to a scutum, which could be slightly shorter than those used by legionaries. The chest of a provocator was protected by scale or lamellar armor called cardiofilax, which was a rarity among gladiators. The equipment of a provocator weighed 10-15 kg. There is evidence of fights against Samnites, murmillos, as well as other provocators.

- Retiarius – (Latin for "net-fighter"). An ancient Roman gladiator armed with a net and a trident. The name literally means "net-fighter" or "net-man." The retiarius wore a manica with a shoulder guard, a subligaculum, and a balteus. Their weaponry consisted of a trident (tridens), a net (rete, retia), and a dagger-pugio on their belt. To finish off a defeated opponent, the retiarius could use a four-pronged fork called a quadrens. As one of the primary weapons of the gladiator was a throwing weapon (the net), they were sometimes referred to as "iaculator" (from Latin iaculator, meaning "thrower").

- Secutor (Latin for "pursuer"). Secutors were also called contraretiarii ("opponents of the retiarius") or contraretes ("against the net"). Sometimes historians consider secutors as a variant of murmillo, as they were similarly equipped, and the main difference was the helmet, which also covered the entire face but lacked the mesh visor. However, this was sufficient even for protection against the trident. The helmet was almost round and smooth, designed to prevent the net of the retiarius from getting caught on it. Like other gladiators, the secutor wore a subligaculum and a balteus. Until the Late Empire, secutors were the most popular type of gladiator.

- Scissor (Latin for "cutter" or "slasher"). They were armed with a gladius and a special crescent-shaped wrist blade. The name of the gladiator comes from the Latin word "scindo" which means "to cut" or "to slash." Another name, "arbalest," is mentioned by the ancient Greek writer Artemidorus Daldianus in the treatise "Oneirocritica." It possibly derives from the ancient Greek word "arbēlos," which referred to a crescent-shaped shoemaker's knife that the gladiator held in their left hand instead of a shield. With this weapon, they inflicted shallow but heavily bleeding wounds on their opponents. In addition to the blade, the scissor was armed with a gladius or pugio held in the right hand. The fighter was protected by a closed helmet, lamellar armor, manica, and short greaves. The scissor, like the dimachaerus, did not carry a shield.

- Thraex (Latin for "Thracian"). Thraex gladiators wore a subligaculum, balteus, manica, a large closed helmet adorned with a crest and a griffin, which was a symbol of the goddess Nemesis, as well as a small shield and two large greaves. Their weapons included a gladius or a small curved Thracian sword called a sica, which was a cunning weapon allowing unexpected strikes to the weakly protected rear parts of the opponent's arms and legs, as well as circumventing the opponent's shield with strikes. Many historians consider Thraex, like secutors, to be a subtype of the murmillo. They most often fought against murmillos, hoplomachi, provocators, retiarii, or secutors in the arena.

Rare types of gladiators about which little is known:

- Veles (Latin for "veles"). Veles were gladiators armed with throwing gastae (darts). The veles gladiators followed the weaponry and tactics of the ancient Roman light infantry veles, hence their name. There are no surviving images of veles gladiators, so little is known about their equipment.

- Gallus (Latin for "Gaul"). They were equipped with a spear, a helmet, and a small Gaulish shield. They quickly disappeared as a type, transforming into murmillos, who were recruited specifically from Gauls, while the niche of spearmen in the arena was filled by hoplomachi.

- Laquearius (Latin for "lasso fighter"). Laquearii may have been a variation of retiarii who tried to catch their opponents using a lasso (laqueus) instead of a net.

- Paegniarius (Latin for "whip fighter"). They used a whip, a club, and a shield attached to the left hand with straps.

- Crupellarius (Latin for "fully armored"). This was the type of heavily armored gladiator whose armor consisted of segmental armor (lorica segmentata), two manicae (one on each arm), and tall segmental greaves reaching the thighs. In terms of protection, crupellarii surpassed not only other gladiators of that period but also any ancient warrior in general.

- Sagittarius (Latin for "archer"). Archers armed with a flexible bow capable of shooting arrows at long distances.

- Samnite (Latin: samnis). Samnites were an ancient type of heavily armed fighters that disappeared in the early Imperial period. Historical Samnites were an influential alliance of Italian tribes living in the Campania region south of Rome, against whom the Romans waged wars from 326 to 291 BC. The equipment of Samnite gladiators included a scutum (shield), a feathered helmet, a short sword, and possibly greaves on the left leg.

- Essedary (Latin for "charioteer"). Essedarii were gladiators who fought from a chariot, and the name derived from the Latin word for Celtic chariot - esseda. It is possible that essedarii were first brought to Rome by Julius Caesar from Gaul. They are mentioned in many descriptions starting from the 1st century AD. Since no images of essedarii have survived, nothing is known about their equipment and fighting style, but it is presumed that they were equipped similarly to equites (Roman cavalry).

Specific types of gladiators:

- Gladiatrix. Female gladiators. There were the same types of gladiatrix equipped just like male gladiators.

- Andabat (from the Greek word "άναβαται" meaning "elevated, blindfolded"). Gladiators who fought each other blindfolded or nearly blindfolded. They wore helmets with solid face covers without eye openings. Sometimes, small openings were present in the helmets to allow the andabatae to have some limited orientation through sound.

- Bustuarius (Latin for "funeral pyre gladiator"). These gladiators fought in honor of the deceased in ritual games during funeral ceremonies.

- Rudiarius (Latin for "freed gladiator"). Gladiators who had earned their freedom (awarded a wooden sword called a rudis) but chose to remain as gladiators. Not all rudiarii continued to fight in the arena; there was a special hierarchy among them. They could become trainers, assistants, judges, fighters, and more. Rudiarii fighters were highly popular among the audience because they possessed immense experience, and one could expect a real show from them.

- Tertiarius (Latin for "tertiary gladiator"). In some competitions, three gladiators participated. Initially, the first two fought each other, and then the winner of that match fought against the third, who was referred to as the tertiarius. Tertiarii also served as substitutes if a gladiator scheduled to fight couldn't enter the arena for various reasons. Hence, they had another name, "suppositicius" meaning "replacements."

- Venator (Latin for "hunter"). They specialized in staged animal hunts but didn't engage in close combat with the animals, unlike bestiarii. Venatores often performed tricks with animals, such as putting their hand into a lion's mouth, riding a camel while leading lions on a leash, or making an elephant walk on a tightrope (Seneca Ep. 85.41). Strictly speaking, venatores were not gladiators, but their performances were part of gladiatorial shows.

Equipment

The equipment of gladiators varied significantly depending on their types, but the following elements were particularly common:

- Helmet. It should be noted that helmets could differ greatly among different types of gladiators

- Oсrea. Greaves were of two types: short and long (above the knee). Many types of gladiators wore greaves only on one leg

- Gladius (or other weapons specific to certain types of gladiators, such as a sika, spear, trident, etc.)

- Shield. There was no standardized shield design for gladiators. The most common were truncated versions of the scutum, but there were also other types

- Torso protection. Most gladiators fought with bare torsos, but in rare cases, they could wear a cardiophylax (breastplate), chainmail (lorica hamata), scale armor (lorica squamata), or even segmented armor (lorica segmentata).

Reenactment

Before beginning the reconstruction of a gladiator's appearance, it is necessary to choose their type to avoid creating an "abstract" gladiator. Gladiator outfits are no less costly than legionary outfits, and the main cost is attributed to the helmet due to its complex production. It should be noted that gladiators did not wear footwear during battles, but since sand arenas are relatively rare in modern events, it is permissible to create caligae as a stylization element. Therefore, the minimum set for a gladiator that is necessary for any type would include a subligaculum, balteus, and caligae. The rest of the elements should be selected depending on the type of gladiator being reconstructed. The least expensive kits would depict gladiators who did not use helmets, such as retiarii. However, when choosing a gladiator type, it is recommended to consider your preferences in terms of offensive weapons rather than the complexity of reproducing the outfit. If you prefer classical swordsmanship, the best choices would be secutor, murmillo, Thracian, or provocator. If you favor the use of a spear, then hoplomachus would be suitable. If you enjoy fighting with two weapons, then dimachaerus or scissor would be appropriate. It is also not recommended to attempt reconstructing gladiator types about which little is known. It is best to focus on the classical depictions described in the section "Most Common Types of Gladiators."

Related topics

Gladius, Balteus, Manica, Ocrea, Subligaculum, Shield, Provocator, Crupellarius

Literature

Gladiators-Konstantin Nosov. pdf

Arena and Blood - Goroncharovsky.pdf

Goroncharovsky V. A. Arena and Blood: Roman Gladiators between Life and Death. - St. Petersburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie, 2009. - 256 p. - (Militaria Antiqua). — 2000 copies. — ISBN 978-5-85803-393-6.

Losev A. F. Gladiators / / Hellenistic-Roman aesthetics of the I-II centuries A.D.-Moscow: MSU Publishing House, 1979. - pp. 45-55.

Matthews Rupert. Gladiators / Translated from English by N. V. Mikelishvili. - Moscow: Mir knigi, 2006. - 320 p.: ill. - ISBN 5-486-00803-1.

Paolucci Fabrizio. Gladiators. Doomed to death / Translated from Italian-M.: Niola-Press, 2010. - 128 p.: ill. — (Secrets of history). — ISBN 978-5-366-00578-4.

Hoefling Helmut. Romans, slaves, gladiators: Spartacus at the Gates of Rome / Translated from German, afterword. and comm. by E. V. Lyapustina. - Moscow: Mysl, 1992. - 270 p.: ill. - ISBN 5-244-00596-0.

Junkelmann, Marcus. Familia Gladiatoria: The Heroes of the Amphitheatre // Gladiators and Caesars: The Power of Spectacle in Ancient Rome / Eckart Köhne, Cornelia Ewigleben, Ralph Jackson. — Berkeley — Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2000. — P. 31—74. — 153 p. — ISBN 0520227980.

Wisdom, Stephen. Gladiators: 100 BC–AD 200. — Osprey Publishing, 2001. — 64 p. — ISBN 9781841762999.

Nossov, Konstantin. Gladiator: Rome’s bloody spectacle. — Osprey Publishing, 2009. — 208 p. — ISBN 9781846034725.

Gallery

Gallery

Mosaics and frescoes

Mosaics and frescoes

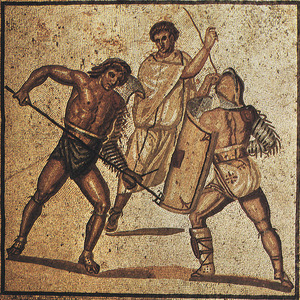

Mosaic with gladiators from Villa Borghese. 3rd century AD

Mosaic with gladiators from Villa Borghese. 3rd century AD

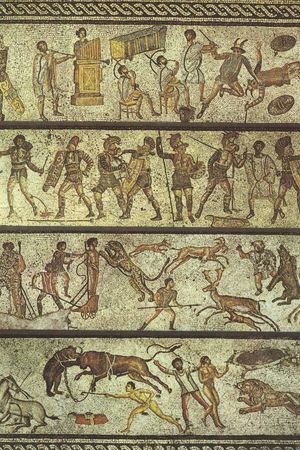

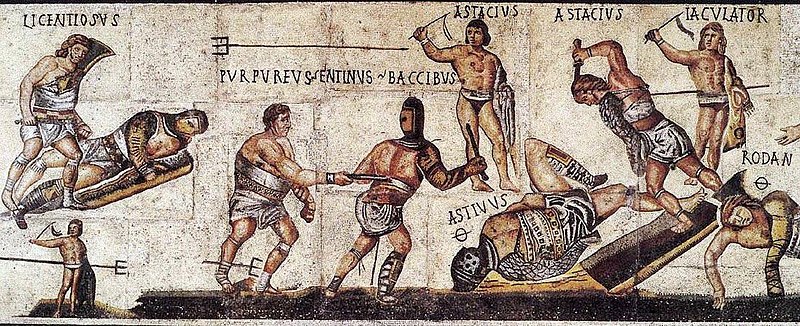

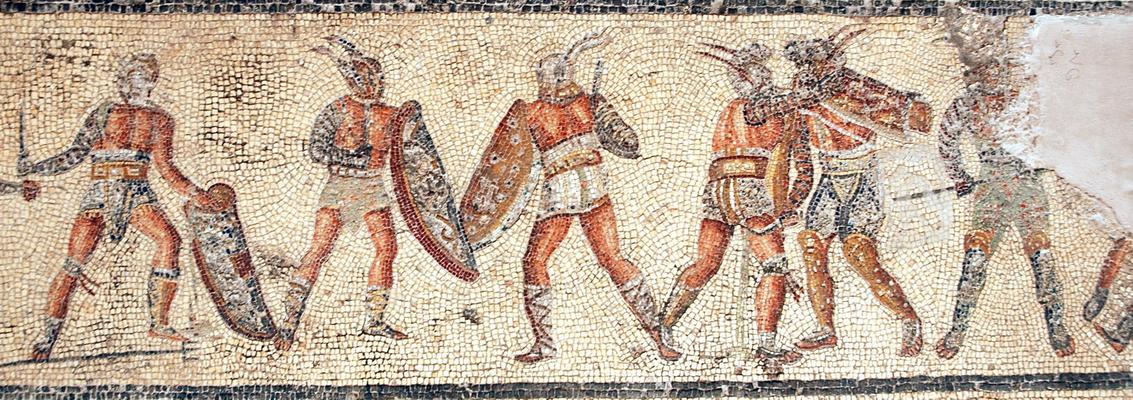

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

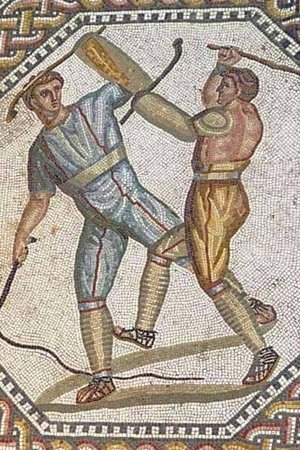

Mosaic with gladiators. 1-3 century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. 1-3 century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

Mosaic with gladiators. Dar Buc Ammera Villa. Tripoli National Museum. Second half of the 1st century AD

Mural with an amphitheater. Found in Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. 1st century AD

Mural with an amphitheater. Found in Pompeii. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. 1st century AD

Bas-reliefs

Bas-reliefs

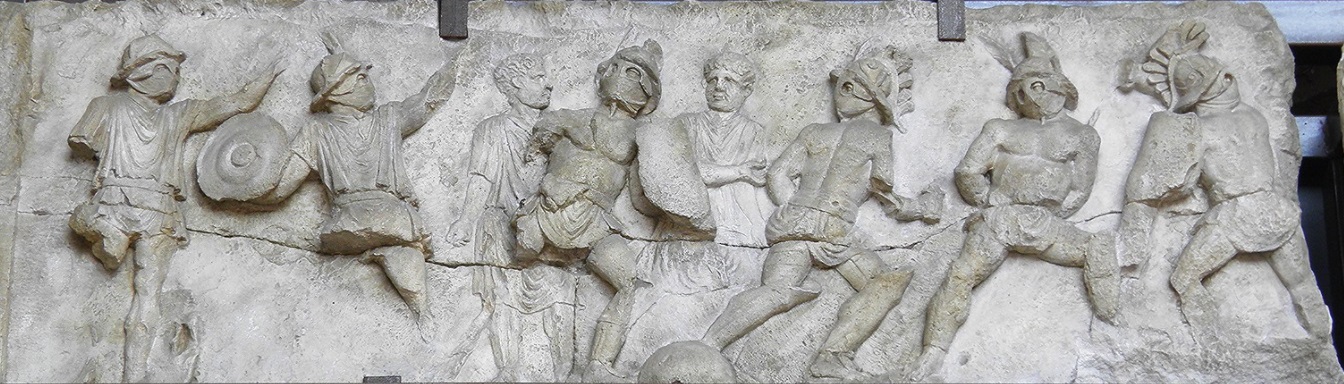

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

Bas-relief in honor of the gladiator games in the city of Teate (Chieti). Colosseum Alley, Rome, AD 20-40

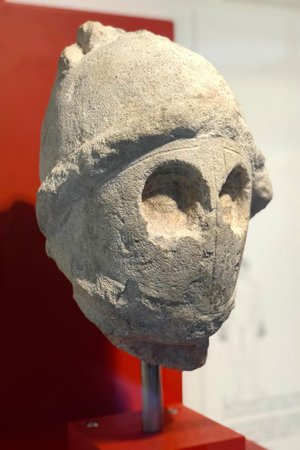

Bas-relief of bustiarii from Amitern. 3-2 century BC

Bas-relief of bustiarii from Amitern. 3-2 century BC

Bas-relief with gladiators. 1-2 century AD

Bas-relief with gladiators. 1-2 century AD

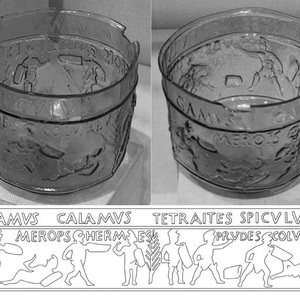

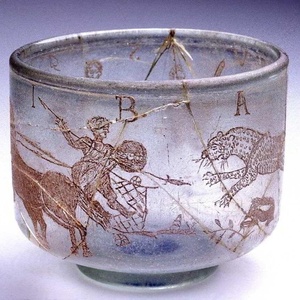

Glass products with gladiators

Glass products with gladiators

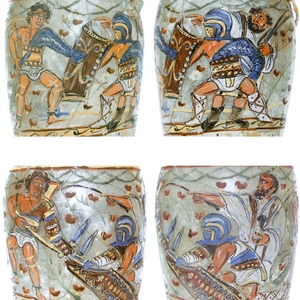

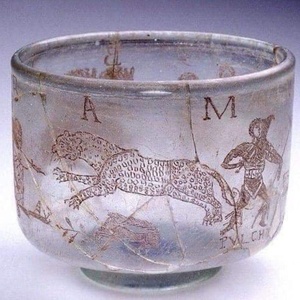

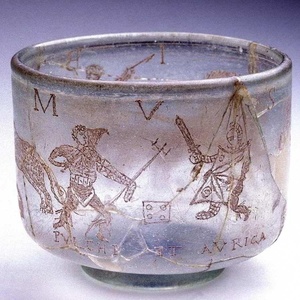

Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250

Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250 Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250

Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250 Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250

Colored painted glass with images of gladiators, found in the Roman fort Vindolanda (Vindolanda), near Hadrian's wall, Northumbria. A.D. 230-250

Figurines

Figurines

Oil lamps with gladiators

Oil lamps with gladiators