Thermae

Thermae (from the Latin thermae, derived from the Greek θερμός, meaning "warm, hot") were ancient baths in classical Greece, initially found in large homes and gymnasiums. During the Hellenistic period, they became widely used by the entire population of cities. In Ancient Rome, thermae were modeled after Greek baths and became central to public life.

Ancient Roman Thermae

The first thermae in Rome were built by Agrippa between 25 and 19 BCE, who bequeathed them for free public use by the Roman population. Nearby, Nero constructed his thermae on the Campus Martius (later renovated by Alexander Severus, hence sometimes called the Baths of Alexander). Close to Nero’s Golden House are the Baths of Titus; to the northeast of these, nearly adjacent, were the Baths of Trajan (104-109 CE), where, during his reign, women were also allowed to bathe. Later, the Baths of Caracalla were erected, officially known as the Baths of Antoninus, located near the Appian Way, behind the Capena Gate, between the Aventine and Caelian Hills. Between the Quirinal and Viminal Hills were the Baths of Diocletian (298-306 CE), which covered 13 hectares. Michelangelo transformed the frigidarium of these baths into the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, which still exists today. The National Museum of Rome is also housed here. Thermae were also built in Roman provinces, such as the imperial baths in Trier.

Inside, imperial thermae were lavishly decorated with marble, mosaics, sculptures, and marble columns, with windows and doors made of bronze. The thermae included various rooms: clothes were left in the changing room (apodyterium), after which visitors could engage in sports or apply oils to their bodies. The bathing "program" began with a cold-water bath in the frigidarium, followed by a warm bath in the tepidarium, and then a hot bath in the caldarium.

Roman architects developed an effective central heating system, known as the hypocaust (hypocaustum), which heated the floors and walls of the thermae. A furnace (praefurnium) was used to heat water and air, which then circulated beneath the floors and within the wall cavities. Double coverings were used to prevent the floor from becoming too hot. The top layer consisted of large bricks, a layer of crushed clay, and the main covering. All of this was supported by small brick pillars (pilae) arranged in a checkerboard pattern. Rectangular, hollow bricks (tubuli) were built into the walls and secured with metal clamps. The interior walls of the baths were decorated with marble or plastered.

Terms:

- Palaestra: A place for physical exercise.

- Apodyterium: Changing room in Roman baths, a vestibule.

- Tepidarium: Warm room.

- Caldarium: The hottest room.

- Hypocaust: Heating system located under the caldarium.

- Laconium (Sudatorium, Hypocaust): A room heated with dry air, featuring a large but shallow pool for washing.

- Labrum: Basin in the laconium.

- Propnigium: Steam room.

- Frigidarium: Cool room with pools.

- Alepterion: A special room where massage and oil applications were performed.

- Balneator: Bath attendant (usually a slave).

Thermal Baths of Caracalla

The Baths of Caracalla (Terme di Caracalla in Italian) were built by Emperor Caracalla in Rome and are officially known as the Baths of Antoninus (Thermae Antoninianae). Located near the Appian Way, behind the Capena Gate, between the Aventine and Caelian Hills, construction began in 212 CE and was completed in 217 CE after the emperor’s death. The courtyard of the Baths of Caracalla measured 400 by 400 meters, with the central complex spanning 150 by 200 meters.

By the 5th century CE, the Baths of Caracalla were considered one of the wonders of Rome. They covered an area of 11 hectares. The main building, the "bathhouse," was set in a park surrounded by a continuous line of various rooms. The bronze frameworks of the enormous semicircular windows in the main hall were fitted with thin plates of translucent ivory-colored stone. This gave the hall a steady, golden light. The walls of polished marble seemed to dissolve into the heights, where an enormous dome appeared to float. The exterior of the Baths of Caracalla was faced with marble slabs; beneath the marble was a massive thickness of local stone and concrete—a mixture of lime with pebbles and sand. The Romans built a shell of the building from bricks or hewn stones and filled it with concrete. As it hardened, the concrete became stronger than stone. Many structures that appear to be made of individual slabs are actually composed of a single piece of hardened concrete. To the right and left of the main entrance were two large exedrae, each with a palaestra in front of it. In the rear part of the garden (opposite the main entrance), in the right and left corners, were two spacious halls, which, judging by their interior equipment, were likely libraries. Low steps ran along the walls, leading to niches where scrolls were stored. In the center between these halls were rows of seats arranged amphitheater-style, curving slightly at both ends. Before them was a stadium, which could be viewed both from the baths themselves (from the rear rooms) and from this amphitheater. Above, cisterns with water for the baths were located: 64 vaulted chambers arranged in two rows and two stories. The water for these cisterns came from the Aqua Marcia aqueduct.

The "bathhouse" had four entrances; the two central ones led to covered halls on either side of the frigidarium. The frigidarium itself was roofless; beyond it, on the same axis, lay a large hall long mistaken for the tepidarium (although it lacked heating facilities), followed by the tepidarium and then the circular caldarium, whose dome (35 meters in diameter) was supported by eight massive pilasters; two of them still stand today. The caldarium was surrounded by small chambers where individuals could bathe privately. On either side of the caldarium were rooms for meetings, recitations, and similar activities.

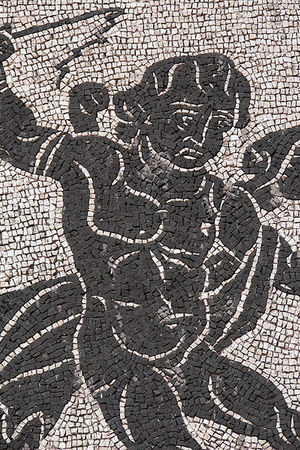

Among the numerous rooms to the right and left of the bathing chambers, there were two palaestrae, two large open courtyards surrounded on three sides by colonnades. These palaestrae were arranged symmetrically: one on the northeast and the other on the northwest side of the building, each with an apse facing out. In the floors of these apses was the famous mosaic with figures of athletes, likely dating to the 4th century CE (discovered in 1824, now housed in the Lateran Museum). Emperors not only sought to artistically adorn their baths, lining the walls with marble, covering the floors with mosaics, and placing magnificent columns, but they also systematically collected works of art. The Baths of Caracalla once housed the Farnese Bull, statues of Flora and Hercules, the torso of the Apollo Belvedere (along with many other lesser statues). People came not only to cleanse themselves but also to relax. The baths were particularly important for the poor. It’s no wonder that one modern scholar called the baths the best gift the emperors gave to the Roman populace. Visitors could find here a club, a stadium, a garden for relaxation, and a cultural center. Each could choose what suited them best: some, after bathing, would sit down to chat with friends, others would watch or participate in wrestling and gymnastics, while still others would stroll through the park, admire the statues, or linger in the library. People left with a renewed sense of vitality, refreshed not only physically but also morally.

In 1960, during the Summer Olympics, gymnastics competitions were held among the ruins of the baths.

Related topics

Latrina, Architecture in Ancient Rome, Theater

Literature

- Strunino-Tikhoretsk, Moscow: Sovetskaya entsiklopediya, 1976 (Bolshaya sovetskaya entsiklopediya: [in 30 volumes] / ch. ed. by A.M. Prokhorov; 1969-1978, vol. 25).

- Thermal baths // Encyclopedic dictionary of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 vols. (82 vols. and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1901. - Vol. XXXIII. - p. 31.

- Sergeenko M. E. "Life of Ancient Rome". M.-L., 1960.

- Hoffmann Th. R. «Die Kunst der römischen Antike». Stuttgart, 2005.