Consul

Consul - the highest elected magistracy in the Roman Republic.

The exact meaning and origin of this term are unknown, which has led to debates among modern scholars. In antiquity, it could be understood as "those who care for" the homeland, citizens, or state, or as "those who consult" the people and the Senate. Historians of the modern era have translated this word differently: Barthold Niburg as "those who are together," Theodor Mommsen as "those who dance together," Ernst Herzog as "those who walk together," Wilhelm Zoltau as "those who sit together," emphasizing their collegial nature.

The position of consul arose after the expulsion of the last king of Rome, Tarquinius Superbus. According to ancient tradition, two consuls were elected. From 509 BCE, consuls were elected by the Senate for a one-year term in centuriate comitia. The position of consul was abolished in 705 CE, 229 years after the fall of Rome.

Initially, consuls were chosen exclusively from the patrician class. However, the struggle between the plebeians and the patricians brought about a change in this tradition, and from 367 BCE, one of the consuls was elected from the plebeians. The first person to hold this position was Lucius Sextius.

From 222 to 153 BCE, consuls assumed office on the Ides of March, which fell on the 15th of March. Later, the consular year began on January 1st.

Consuls held both military and civilian authority. As military leaders, they were the supreme commanders of the Roman army, responsible for recruiting legions, appointing some military tribunes (the other part was elected in the tribune comitia), and leading military operations. Their civilian authority included convening the Senate and popular assemblies, presiding over them, proposing legislation, and overseeing the election of officials. Consuls were the principal executors of the Senate and the people's decrees, responsible for internal security, and oversaw certain festivals and other matters of civilian life.

Since the consuls had equal official powers, each had the right to veto the actions of the other. Despite this, they were required to act jointly in all important civil matters. The question of issuing acts that required individual leadership (such as presiding over comitia) was resolved by lot or by agreement between the parties. During military operations, one consul would be sent to command the troops, while the other would remain in the city. In cases where the war required the presence of both consuls on the battlefield, the distribution of areas of military action between them was determined by lot, agreement, or at the discretion of the Senate. When consular armies acted together and both consuls were present, they alternated in command, changing daily.

Consuls also had assistants known as quaestors.

Consuls had their distinctive insignia: a toga with a broad purple border, a curule chair (sella curulis) adorned with ivory inlays, and an entourage of 12 lictors carrying fasces, into which axes were inserted outside the city walls.

In cases of extreme external or internal danger in Rome, a dictator was appointed by the decision of the Senate. In this regard, the Senate had the right to make the essential decision of whether a dictator was needed at that particular time or not, while the actual appointment was carried out by one of the consuls. The Senate usually indicated the person they desired to see as a dictator, and the consul typically took this preference into account.

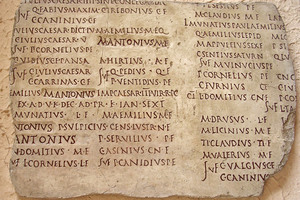

In the Roman system of dating, years were designated by the names of the consuls of that year (they were called "Consules Ordinarii" in Latin).

According to the laws of the Republic, the minimum age for a consul was 41 for a patrician and 42 for a plebeian. However, exceptions were allowed. Gnaeus Pompey the Great became a consul at the age of 27, and Octavian at the age of 19.

Upon completing their term of office, consuls were assigned the administration of a province and held the title of proconsul.

During the Imperial era, consuls lost real governmental power. Their position became an honorary title, as the consular authority now resided with the emperor, and thus the magistracy became an appointive one.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Military campaigns of the Roman Republic, Electoral Process in Ancient Rome, Royal Rome, Legion

Literature

- Consuls // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Kovalev S. I. / Istoriya Rima [History of Rome]. SPb.: OOO "Poligon Publishing House". - 2002. - 864 p.

- Bagnall, Roger S; Cameron, Alan; Schwartz, Seth R; Worp, Klaus Anthony. Consuls of the later Roman Empire. — London: Scholar Press, 1987. — (Volume 36 of Philological monographs of the American Philological Association).