Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (500–449 BCE, with interruptions) were military conflicts between Achaemenid Persia and the Greek city-states that sought to defend their independence. These wars are sometimes referred to simply as the Persian Wars, a term usually applied to the Persian campaigns in the Balkans in 490 BCE and 480–479 BCE.

As a result of the Greco-Persian Wars, the territorial expansion of the Achaemenid Empire was halted, and Ancient Greek civilization entered a period of flourishing and achieved its greatest cultural accomplishments.

Historiography typically divides the Greco-Persian Wars into two (the first from 492–490 BCE and the second from 480–479 BCE) or three wars (the first in 492 BCE, the second in 490 BCE, and the third from 480–479 BCE, or possibly until 449 BCE).

Key Events:

- The revolt of Miletus and other Ionian cities against Persian rule (500/499–494 BCE).

- Darius I's invasion of the Balkan Peninsula, which ended in his defeat at the Battle of Marathon (492–490 BCE).

- Xerxes I’s campaign (480–479 BCE).

- The actions of the Delian League against the Persians in the Aegean Sea and Asia Minor (478–459 BCE).

- The Athenian expedition to Egypt and the conclusion of the Greco-Persian Wars (459–449 BCE).

Background

During the Dark Ages, a large number of people from the ancient Greek tribes of Ionians, Aeolians, and Dorians migrated to the coast of Asia Minor. The Ionians settled on the coasts of Caria and Lydia, as well as the islands of Samos and Chios, where they founded 12 cities. Miletus, Myus, Priene, Ephesus, Colophon, Lebedos, Teos, Clazomenae, Phocaea, Erythrae, Samos, and Chios, recognizing their ethnic kinship, established a common sanctuary called the Panionium. Thus, they formed a cultural union and decided not to admit other cities, even those populated by Ionians. According to Herodotus, the union was rather weak, and only Smyrna sought to join it. During the reign of King Croesus, Ionia was conquered and became part of Lydia. Croesus allowed the Greeks to manage their internal affairs and demanded only recognition of his supreme authority and moderate tribute. The Ionians gained several benefits and easily accepted the loss of their independence.

The rule of Croesus ended with the complete conquest of his kingdom by Cyrus II the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire. During the war with Croesus, the Persians sent an offer to the Ionians to defect from Lydia, which was rejected by all cities except Miletus. After the capture of the main city of Sardis and the capture of Croesus, an embassy was sent to Cyrus from the Greeks living on the coast of Asia Minor. The Ionians agreed to submit to the new ruler on the same terms as to the previous one. The offer was rejected: Cyrus responded to the envoys with a parable about a fisherman who initially tried to lure fish onto land by playing the flute, and after catching them with a net, commanded the struggling fish to "stop dancing" since they did not want to dance to the flute earlier. According to Diodorus, Cyrus, through his general Harpagus, demanded full submission to Persia. The Ionians could not accept the Persian terms and began preparing for war. The treaty between Miletus and Persia likely granted the Milesians autonomy within the Persian Empire, but after Darius I came to power, the "special status" of Miletus was revoked.

Sparta, which by then had become one of the most powerful Greek city-states, maintained close relations with the Lydian kingdom, culminating in a Lydian-Spartan alliance treaty concluded around 550 BCE. This event occurred before the Lydians' war with Persia, and from the Spartans' perspective, the treaty was not directed against any specific enemy. After the war began and the Battle of Pteria was fought, Croesus appealed to the Spartans for military aid. The Spartans decided to assist the Lydians but were too late; during their preparations, they received news that Sardis had fallen and Croesus was captured.

In 545 BCE, at a gathering of Ionian Greeks in Panionium, it was decided to request military assistance from Sparta. The Ionian delegation was refused. The Spartans likely hesitated to engage with an unfamiliar opponent who had defeated the seemingly powerful kingdom of Croesus. However, they sought to preserve their reputation and chose to act diplomatically. A Spartan envoy declared on behalf of the Spartan authorities that the Persians should not launch military actions against the Ionian and Aeolian cities, but Cyrus rejected this warning. After brief resistance, all the Greek cities on the western coast came under full Persian control.

During the reign of Cambyses, the Persians subjugated the Greek cities of Cyprus and Cyrene. In the early years of Darius’s rule, the Persians captured Samos.

In 513 BCE, a large Persian army led by King Darius I crossed from Asia into Europe. Advancing against the Scythians, the Persians subdued the Greek cities in Thrace. Most of the rulers of these cities, realizing the impossibility of resistance, voluntarily acknowledged their dependence on the Persians and joined the campaign against the Scythians. Megabazus, who was left in Europe with the army, brought the local cities that refused to submit to the Persians under control, operating in the region of the Hellespont, Propontis, and along the entire northern coast of the Aegean Sea, up to Thessaly. Otanes, who succeeded Megabazus as satrap of Daskyleion, continued to subjugate the Greek cities on both the Asian and European shores of the Hellespont and Propontis.

Relations between Athens and Persia were complicated by the following circumstance: the Persians had taken in the exiled Athenian tyrant Hippias. The Athenian leader Cleisthenes, fearing an attack by the Spartans, sent an embassy to Sardis in 508/507 BCE to the Persian satrap and brother of the king, Artaphernes. The envoys aimed to secure a defensive alliance against the Spartans. The Persians demanded "earth and water" from the Athenians. The envoys agreed. This symbolic act signified formal recognition of their submission. Although the envoys were severely condemned upon returning home, the Persians began to consider the Athenians as their subjects, similar to the Ionian Greeks. Around 500 BCE, the Athenians sent a new embassy to Artaphernes. The subject of discussion was the presence of Hippias in the Persian camp, who, according to Herodotus, was conducting anti-Athenian propaganda and sought to bring the city under his and Darius’s control. Artaphernes demanded that the former tyrant be returned to his homeland. This was an unacceptable condition for the Athenians, and the demand to return Hippias contributed to the rise of anti-Persian sentiments in Athens.

During the rule of Aristagoras, a revolt occurred on the nearby Greek island of Naxos. The demos expelled several wealthy citizens, who fled to Miletus seeking help. They promised to cover the costs of waging war. Aristagoras pursued personal goals, believing that by restoring the exiles to their homeland, he could become the ruler of the wealthy and strategically located island. The cunning Greek went to Sardis to see the Persian satrap and brother of Darius, Artaphernes, and convinced him to provide military forces. The Persians outfitted 200 warships. The Persian commander was placed under Megabates. The preparations for the military expedition to Naxos were conducted in secret. Officially, it was announced that the fleet was heading in the opposite direction, towards the Hellespont. However, a quarrel erupted between the two commanders, Megabates and Aristagoras. Aristagoras asserted that he was nominally in charge of the campaign and that the Persians should follow his orders without question. According to Herodotus, an enraged Megabates sent a messenger to Naxos, warning them of the impending attack. The islanders had time to prepare for a siege. As a result, after spending substantial resources, the Persians were forced to return home after a four-month siege.

Aristagoras found himself in a difficult position. First, he had failed to fulfill his promises to the king's brother, Artaphernes; second, he needed to pay large sums to maintain the army; and third, his quarrel with the king’s relative Megabates could cost him his power over Miletus and his life. All these concerns led Aristagoras to consider starting a revolt against the Persians. A letter from Histiaeus, who was at the king’s court, pushed him towards open rebellion.

At a military council of Aristagoras’s supporters, it was decided to begin an uprising. The rebellion quickly spread not only to the cities of Ionia but also to Aeolia, Caria, Lycia, and even Cyprus. Everywhere, tyranny was overthrown, and democratic forms of government were established. In the winter, Aristagoras traveled to mainland Greece to seek allies. In Sparta, King Cleomenes I refused to help, but the Athenians sent 20 ships to aid the rebels. The Eretrians also equipped five ships to support the uprising.

In the spring of 498 BCE, the Athenians and Eretrians arrived to support the rebels. They joined forces with the main body near the city of Ephesus. Aristagoras relinquished command of the troops, passing leadership to his brother Charopinus and a certain Hermophantus. At this time, Persian forces were advancing towards Miletus to destroy the center of the rebellion. Instead of marching to aid Miletus, the insurgents turned towards the Lydian satrapal capital and one of the empire's most important cities, Sardis. The satrap and brother of the king, Artaphernes, was taken aback, finding himself in an unprotected city. The Persian garrison retreated into a fortified area. A Greek soldier set one of the houses on fire. Soon, the flames engulfed the entire city. Along with residential buildings, the temple of the local goddess Cybele was also burned down. The local residents were angered by this turn of events and took up arms. The Greeks were forced to retreat to the coast.

Upon learning of what had happened, Persian satraps from nearby territories sent their troops to Sardis. By the time they arrived, the insurgents had already left the half-ruined city. Following them, the king’s army caught up with the retreating forces near Ephesus. In the ensuing battle, the Greeks suffered defeat and were forced to retreat. Despite Aristagoras’s pleas, the Athenians returned home.

The capture and burning of Sardis had serious consequences. Hearing of the seemingly brilliant success of the uprising, many cities in Asia Minor and Cyprus joined it. The Lydians saw the burning of the temple of Cybele as a desecration of a sacred site. In the empire’s capital of Susa, the devastation of Sardis left a deep impression. The Persians began to act more swiftly and energetically, whereas, without this event, they might have regarded the uprising as more insignificant. According to Herodotus, Darius was determined to avenge the Athenians after hearing of the incident.

Under the energetic leadership of Artaphernes, Sardis became the center of military preparations. Since there was a danger of the Scythians joining the rebellious Ionians, an army led by Darius’s son-in-law Daurises was sent to the northwestern part of Asia Minor, to the region of the Propontis (Marmara Sea). Daurises's actions were successful. He quickly (according to Herodotus, he conquered each city in one day) managed to capture Dardanus, Abydos, Percote, Lampsacus, and Pessinus. Having conquered the Hellespontine region, Daurises moved to subdue the rebellious Caria.

In Caria, the Persians won two victories — near the confluence of the Marsyas River with the Maeander and near the sanctuary of Labraunda. However, the Persians could not capitalize on their successes. Learning of their movements, the Carians managed to set a trap on the way to the city of Pedasus, where the entire enemy army, including the commander Daurises, was destroyed. The loss of an entire army forced the Persians to halt their advance. The following two years (496 and 495 BCE) passed relatively peacefully, with neither side conducting active offensive operations.

By 494 BCE, the Persians prepared for a large-scale offensive. Their goal was to subdue the center of the rebellion, Miletus. They assembled an army and fleet large by ancient standards. Their forces included inhabitants from several subjugated peoples, including Phoenicians, Cypriots, Cilicians, and Egyptians. Overall command was entrusted to Datis.

Seeing the Persians' preparations, the rebels gathered for a council at Panionium. It was decided not to field a combined land force against the Persians, leaving Miletus to defend itself. At the same time, the Greek cities agreed to outfit a joint fleet to protect the city from the sea. Upon arriving at Miletus, the Persian commanders decided that they first needed to defeat the fleet; otherwise, a siege of the city would be ineffective. They succeeded in sowing discord among the Greeks. In the naval Battle of Lade, due to treachery, the Greeks were defeated. This defeat sealed Miletus's fate.

After a siege, the city was stormed, the men were killed, and the women and children were enslaved.

During Daurises’s campaign in the Hellespont and Caria in 497 BCE, the army of Artaphernes and Otanes attacked Ionia and neighboring Aeolis. The Persians managed to capture two cities — Clazomenae and Cyme. However, after Daurises’s defeat, the offensive operations ceased. During the Persian advance, Aristagoras fled from Miletus to a colony of his father-in-law, Histiaeus, which had been gifted to him by Darius. He soon died during the siege of a Thracian city.

After the fall of Miletus, the rebellion was lost. After wintering, the Persians systematically captured all the cities that had slipped from their control. According to Herodotus, they treated the rebels with extreme cruelty, conducting manhunts, turning young boys into eunuchs for harems, and sending attractive girls into slavery. The inhabitants of some cities abandoned their homes. Among those who fled the wrath of the Persians was Miltiades, who, a few years later, achieved a brilliant victory at Marathon.

Mardonius' Campaign

The failure of the Ionian Revolt, which was caused by a lack of solidarity among the Greek cities, greatly encouraged Darius. In 492 BCE, Darius' son-in-law Mardonius advanced with a large army and strong fleet towards Greece through Thrace and Macedonia. After conquering the island of Thasos, his fleet sailed westward along the coast but was struck by a terrible storm near Mount Athos, resulting in the loss of about 300 ships and 20,000 men. Mardonius’ land army was attacked by the Thracian tribe of the Bryges and suffered heavy losses. Mardonius settled for the subjugation of Macedonia, postponing the attack on Hellas, but Darius prepared for a new campaign. In 491 BCE, Persian envoys were sent to Hellas by the Persian king with a demand for “earth and water” as a sign of submission. These symbols of subjugation were given not only by most of the islands, including Aegina, but also by many cities, such as Thebes. In Athens and Sparta, however, the envoys were killed. The willingness of the islands and many mainland communities to submit was explained not only by the might of Persia but also by the struggle between aristocrats and democrats: tyrants and aristocrats were ready to submit to the Persians in order to prevent the democratic party from gaining an upper hand. The national independence of the Greeks faced a great threat, which could only be eliminated by forming a large alliance. The Greeks began to awaken to a sense of national unity. The Athenians appealed to Sparta, demanding punishment for the cities that had betrayed them, thus recognizing its leadership over Greece.

Datis and Artaphernes hike

Darius relieved Mardonius of command and appointed his nephew Artaphernes in his place, giving him the experienced Median general Datis. The main objectives of the military expedition were the conquest or subjugation of Athens and Eretria on the island of Euboea, which had also supported the rebels, as well as the Cycladic Islands and Naxos. According to Herodotus, Darius ordered Datis and Artaphernes to "enslave the inhabitants of Athens and Eretria and bring them before his royal eyes." The former tyrant of Athens, Hippias, also accompanied the expedition.

During the campaign, the Persian army conquered Naxos and landed on the island of Euboea in mid-summer 490 BCE. When this happened, the inhabitants of Eretria decided not to abandon the city and attempted to withstand the siege. The Persian army not only laid siege to the city but also attempted to storm it. Herodotus wrote that the struggle was fierce and both sides suffered heavy losses. Nevertheless, after six days of fighting, two prominent Eretrians, Euphorbus and Philagrus, opened the gates to the enemy. The Persians entered the city, looted it, and burned the temples and sanctuaries in retaliation for the burning of Sardis. The captured citizens were enslaved. From Euboea, the Persians crossed the narrow Euripus Strait to Attica and set up camp at Marathon. The plain of Marathon was well-suited for the operations of the strong Persian cavalry.

The imminent danger caused confusion in Athens. Among the Athenians, there were both supporters and opponents of resistance. Miltiades managed to organize the mobilization of all forces for armed resistance by passing a decree through the popular assembly. Miltiades' decree called for the enlistment of all able-bodied male citizens in the city’s militia and the liberation of some slaves to reinforce the army. Despite all efforts, only about 9,000 hoplites were gathered. A messenger was sent to Sparta to request help, but the Spartans delayed, citing religious obligations. The inhabitants of the Boeotian city of Plataea sent all their militia, numbering one thousand men, to assist the Athenians.

The Athenian and Plataean troops marched to Marathon. Waiting for the Persian forces in the city was unwise: the walls were not well-fortified, and there could have been traitors within the city. The Athenians set up camp at Marathon, not far from the Persians. The nominal commander was the archon-polemarch Callimachus, and under him were ten strategoi (generals), who took turns commanding the army, including Miltiades. Of these, Miltiades was the most talented, experienced, and energetic. The strategoi debated the next course of action against the Persians. Miltiades urged for an immediate decisive battle, while others advocated a cautious approach, fearing the superiority of the Persian forces. The strategoi were divided: five were in favor of battle, including Miltiades and Aristides, while five were against. Miltiades convinced Callimachus of the necessity of immediate battle. Then all the strategoi, following Aristides’ lead, gave up their days of command to Miltiades. Miltiades devised the battle plan and implemented it.

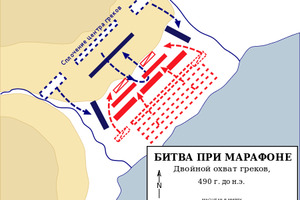

The Athenian army took up a position on the Pentelic Ridge, difficult to attack and effectively blocking the road from Marathon to Athens. The Persians, who had numerical superiority, neither attacked the Greeks nor attempted to outflank them. Datis decided to re-embark his troops and land the army at Phalerum, near Athens. Once most of the Persian cavalry and some of their infantry were back on the ships, Miltiades decided to attack the Persians. Considering the Persians' two-to-one superiority in numbers, Miltiades stretched the Athenian phalanx thinly along the front to avoid being encircled, strengthening the flanks at the expense of the center, and then launched a sudden, swift attack, taking advantage of the tight formation of the Greek hoplites over the loose formation of the lightly armed Persians, supported by cavalry and archers.

On September 12, 490 BCE, the Athenians and Plataeans launched a surprise attack on the Persians. The tight formation of the Greek hoplites initially drove back the lightly armed Persian troops. Persian cavalry, stunned by the Greeks’ assault, could not effectively participate in the battle. The center of the Greek army retreated slightly under pressure from the superior Persian forces, but this was part of Miltiades' plan. He ordered the flanks to turn inward and strike the rear of the Persians who had broken through the center. This maneuver led to the encirclement and destruction of a significant portion of the enemy forces. The surviving Persians retreated to their ships and immediately set sail.

Leaving Marathon, the Persian ships sailed around Attica, attempting to seize Athens, which was left defenseless while the entire city militia was on the battlefield, 42 kilometers away. However, Miltiades immediately led the entire army, without rest after the battle, on a forced march in full armor to Athens, reaching it before the Persian fleet. Seeing that the city was well-defended, the demoralized Persians, having achieved nothing, departed back home. The Persian punitive expedition ended in failure.

The Athenians and Plataeans, under the command of Miltiades, won a brilliant victory. In the battle, 192 Greeks and 6,400 Persians perished. The victory boosted the morale of the Athenians and remained in their memory as a symbol of Athens’ greatness.

Xerxes ' Campaign

In the spring of 480 BCE, the Persian army crossed the Hellespont (modern-day Dardanelles) from Asia into Europe. Xerxes personally led this new invasion of Greece. The ruler of the Achaemenid Empire managed to amass an enormous force for this purpose. Herodotus mentions the fantastic number of over 5 million men in Xerxes’ land army. Most modern scholars are skeptical of this report, with some historians estimating Xerxes had no more than a few tens of thousands of soldiers. However, the truth likely lies somewhere in between, with a more plausible estimate being that the Persian army consisted of several hundred thousand men. Regardless, even this number far exceeded the forces the Greeks could muster.

Xerxes' army was accompanied by a fleet that included around 1,200 ships. This massive Persian fleet included not only Phoenician vessels but also ships from Greek city-states in Asia Minor and nearby islands under Achaemenid control. By ordering his Greek subjects to provide military forces for the campaign, the Persian ruler sought to test their loyalty to the Achaemenid Empire.

After crossing the Hellespont on a specially constructed pontoon bridge, Xerxes followed the same route Mardonius had taken earlier—along the northern coast of the Aegean Sea. The fleet accompanied the army, moving close to the shore. To avoid shipwrecks while rounding Mount Athos, the Persians dug a canal through the two-kilometer isthmus, allowing their ships to pass through safely. Xerxes' hordes flooded Thrace and Macedonia and invaded Greek Thessaly. The Thessalian cities mostly surrendered to the Persians voluntarily.

For the Greek city-states that were members of the Hellenic League, it was time to immediately take up defensive positions. The initial plan was to hold back the Persians at the pass of Tempe (in northern Thessaly). However, this plan had to be abandoned due to the pro-Persian stance of the Thessalians. Instead, the Greeks chose the pass of Thermopylae as their defensive position, as it served as a natural boundary between northern and central Greece. Although the Spartans, who held overall command of the military operations, initially favored defending the Isthmus of Corinth to block access to the Peloponnesus, this would have left Athens defenseless. Only at the insistence of the Athenians did Sparta agree to send a small allied force to Thermopylae under the leadership of King Leonidas. This force consisted of about 7,000 men, including 300 Spartans, who formed the elite core. At the same time, the Greek fleet moved out to confront the Persians, taking positions near Thermopylae at the northern tip of the island of Euboea.

The Persians took Athens, burning and destroying the defenseless city and killing hundreds of elderly citizens who refused to abandon their homes. Soon, the Persian fleet approached Athens as well. However, Xerxes was met with a trap: Themistocles managed to force the Persians into a naval battle in the strait between Salamis and Attica. In late September 480 BCE, the famous Battle of Salamis took place, becoming the climax of all the Greco-Persian Wars. Of the total Greek fleet (380 ships under the command of the Spartan navarch Eurybiades), nearly half was made up of the Athenian squadron (180 ships), led by Themistocles. Fearing defeat due to the enemy's numerical superiority, Eurybiades initially wanted to avoid battle and withdraw to the Isthmus, but Themistocles made every effort to ensure the battle took place.

In the narrow strait, the Persian fleet could not exploit its numerical advantage. The numerous large and unwieldy Persian ships lost control and became crowded together. The more agile and maneuverable Greek triremes pressed the enemy ships, boarded them, and sank them with ramming attacks. Persian sailors attempting to escape to shore were cut down by Greek warriors commanded by Aristides. The battle ended in a complete and unequivocal victory for the Greeks, with Athenian ships making a decisive contribution.

After the defeat at Salamis, Xerxes was forced to return home with the remnants of his fleet. However, the danger was not yet over for the Athenians who returned to the ruins of their city: a substantial Persian land army, several tens of thousands strong, remained in Greece under the command of the experienced general Mardonius. Making Boeotia his base, this army moved through Greece, spreading destruction wherever it went. The Persians even managed to briefly recapture Athens, and Mardonius planned to invade the Peloponnesus next. In 479 BCE, the Greek city-states of the Hellenic League managed to assemble a combined force comparable in size to the Persian army. The battle with the Persians took place in southern Boeotia, near the town of Plataea, and was hard-fought on both sides. In the Battle of Plataea, the Greek phalanx under the command of the Spartan general Pausanias once again demonstrated its superiority, delivering a decisive defeat to the Persian forces. Mardonius was killed, and the remnants of his army fled Greece.

Parallel to the land campaign on the Balkan Peninsula, the Hellenic League continued naval operations. The combined Greek fleet, commanded by Spartan King Leotychides and Athenian strategist Xanthippus, approached the coast of Asia Minor, where the Persians were preparing reserve forces that could potentially launch a new invasion of Greece. In the Battle of Mycale, which unfolded simultaneously on land and at sea, these Persian reserve forces were destroyed. This battle occurred on the same day as the Battle of Plataea, which was likely not a coincidence; it suggests that the Greeks had a coordinated plan of action on all fronts.

The battles of Plataea and Mycale marked the end of the most crucial phase of the Greco-Persian Wars. The victories achieved by the Greeks during this phase led to a decisive turning point in the conflict. The strategic initiative shifted to the Greeks, and the Achaemenid ambitions of ruling Greece were decisively ended.

Further Military Actions

One of Xerxes’ main generals, Mardonius, asked the king to leave him part of the land army for further warfare. After brief consideration, Xerxes agreed. Mardonius and his army settled for the winter in Thessaly and Boeotia, while the Athenians were able to return to their plundered city. During the winter, the Greek allies gathered again in Corinth to celebrate victory and discuss further military actions.

Athens found itself in a difficult position due to the looming threat from Mardonius’ Persian army, while the Spartans remained in the Peloponnese, constructing defensive structures on the Isthmus. Mardonius entered into negotiations with the Athenians and offered them a separate peace. During discussions in the Assembly, Aristides insisted that the Persians be refused. Mardonius then occupied Athens, and the Athenians were forced to evacuate to Salamis once more. An embassy, including Cimon, Xanthippus, and Myronides, was sent to Sparta at Aristides’ suggestion, with a demand for assistance. The embassy warned that if help was not provided, "the Athenians would find their own means of salvation." As a result, an army led by the regent Pausanias, guardian of the young son of the deceased King Leonidas, set out on a campaign.

An Athenian militia of 8,000 men under the command of Aristides was sent to Boeotia. Plutarch claimed that Aristides held the position of strategos autokrator (general with unlimited powers during military operations). The Battle of Plataea ended in a crushing defeat for the Persians.

According to legend, on the same day as the Battle of Plataea, the allied fleet defeated the demoralized remnants of the Persian navy in the Battle of Mycale. This marked the end of the Persian invasion and the beginning of the next phase of the Greco-Persian Wars, the Greek counter-offensive. After Mycale, the Greek cities of Asia Minor rose in revolt again, and the Persians were unable to reclaim them. The allied fleet then sailed to the Chersonese, occupied by the Persians, and laid siege to and captured the city of Sestos. The following year, 478 BCE, the allies dispatched forces to seize the city of Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul). The siege was successful, but the harsh behavior of the Spartan commander Pausanias toward the allies caused much dissatisfaction and led to his recall.

After the siege of Byzantium, Sparta sought to withdraw from the war. The Spartans believed that after the liberation of mainland Greece and the Greek cities of Asia Minor, the war’s objectives had been achieved. There was also the opinion that it was impossible to ensure the independence of the Asian Greeks. In the Hellenic League of Greek city-states, which fought against Xerxes’ forces, Sparta and the Peloponnesian League dominated. After Sparta’s withdrawal from the war, leadership of the Greek forces passed to the Athenians. A congress was convened on the sacred island of Delos to create a new alliance for the continuation of the struggle against the Persians. This alliance, which included many of the Aegean islands, was officially called the "First Athenian League," but is more commonly known in historiography as the Delian League. According to Thucydides, the official aim of the league was "to avenge the barbarian for the calamities he had caused by ravaging Persian territory." In the following decade, the forces of the Delian League expelled the remaining Persian garrisons from Thrace and expanded the territories controlled by the league.

After the defeat of the Persian forces in Europe, the Athenians began expanding the alliance in Asia Minor. The islands of Samos, Chios, and Lesbos likely became members of the Hellenic League after the Battle of Mycale and were probably among the first members of the Delian League. However, it is unclear when exactly other Ionian cities or other Greek cities of Asia Minor joined the league. Thucydides mentions the presence of Ionians in Byzantium in 478 BCE, so it is possible that some Ionian cities joined the league as early as 478 BCE. The Athenian politician Aristides, according to one version, died in Pontus (around 468 BCE), where he had sailed on public business. Since Aristides was responsible for ensuring that each member of the league paid their dues, this trip may be related to the expansion of the league in Asia Minor.

In 477 BCE, Cimon conducted his first successful military operation. The siege of the city of Eion at the mouth of the Strymon River ended with the besieged Persians setting the city on fire and perishing in the flames. The capture of the city allowed the Greeks to begin colonizing the attractive region of the Strymon.

In 476 BCE, Cimon conducted another successful military campaign. After capturing the island of Scyros in the northwestern Aegean, he expelled the pirates who had settled there and were hindering the normal development of maritime trade. According to legends, the mythological hero and former king of Athens, Theseus, was killed on the island. After diligent searches, Cimon claimed to have found the remains of Theseus. Whether the bones brought to Athens belonged to Theseus or not, this episode increased Cimon’s popularity among the people.

In 471 BCE, Cimon expelled the Spartan regent Pausanias from Byzantium. The former victor of the Battle of Plataea had become uncontrollable. He had seized the strategically important city on his own and ruled it as a tyrant. This situation was unsatisfactory to everyone, including the Spartans. The captured city became part of the Delian League, further strengthening Athenian power. According to legend, during the distribution of the spoils, Cimon ordered that on one side the Persian prisoners be placed and on the other their gold jewelry. He then offered the allies to choose either part, with the other going to the Athenians. Everyone thought that Cimon had made a fool of himself. The allies took the valuables, leaving the Athenians with the bare bodies of people unaccustomed to physical labor. Soon, friends and relatives of the prisoners began to ransom them, allowing Cimon to collect significant funds.

Shortly after the expulsion of Themistocles, Cimon won one of the most resounding victories of the Greco-Persian Wars at the Battle of the Eurymedon. In a single day, he achieved a "triple" victory in two naval and one land battle against superior enemy forces.

The Athenians learned that large Persian naval and land forces were gathering at the mouth of the Eurymedon River (in southwestern Asia Minor) for an invasion of Greece. Leading a fleet of 200 ships, Cimon arrived at the Persians' location and caught them by surprise. Most of the Persians were onshore. Because of this, the Greeks managed to destroy the enemy fleet and capture 200 triremes. The Persians hesitated, waiting for reinforcements of 80 Phoenician ships that were approaching the battle site. The Greeks, having landed on the shore, engaged the enemy and defeated the land army. The battle did not end there. On Cimon’s orders, the Greeks returned to their ships and defeated the approaching Phoenician fleet at the Eurymedon.

The crushing defeat at the Eurymedon forced the Persian king to negotiate. An Athenian embassy, led by Cimon’s brother-in-law Callias, was sent to Susa. The details of the peace treaty (effectively a truce, known as the Peace of Callias) are unknown, but its terms were clearly favorable to the Athenians.

The period between the Battle of the Eurymedon (469 or 466 BCE) and the Athenian expedition to Egypt (459–454 BCE), which spanned at least 10 years, was characterized by an absence of military actions between the Persians and Greeks. It was during this time that a military conflict—the small Peloponnesian War—erupted between the Spartans and Athenians, who had previously been allies in the anti-Persian coalition.

In 450-449 BCE, Cimon once again campaigned against the Persians, but died in the same year, leaving a legacy as the last great leader of the Greco-Persian Wars. Despite the double glorious victory of the Greeks at Salamis, Athens had to abandon offensive actions against Persia, as difficult tasks lay ahead within the state, and the fateful enmity with Sparta had already begun.

Results

Persia lost its possessions in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of the Hellespont and the Bosphorus, and recognized the political independence of the city-states of Asia Minor.

The Greco-Persian Wars were of great importance to Greece. They accelerated the development of Greek culture and instilled in the Greeks a sense of their own greatness. The Greeks saw their success as a victory of freedom over tyranny. National independence and civil liberty, linked to the developing democracy, were preserved. Since the advantage lay with Athenian democracy, almost all Greek states were swept up in the democratic movement after the Greco-Persian Wars. Athens became a great naval power and the center of Greece, culturally, politically, intellectually, and economically.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Athens, Delos Maritime Union, Alexander the Great, Alexander the Great's Military Campaigns

Literature

- Herodotus. Ἱστορίης ἀπόδειξη (История)

- Thucydides. συγκραφή (History of the Peloponnesian War)

- Xenophon. Κύρου ἀνάβασις (Анабасис)

- Plutarch. ΒίΟι παράλληλοι (Comparative biographies): Themistocles, Aristides, Pericles

- Diodorus of Sicily. Ἱστορικὴ βιβλιοθήκη (Historical Library)

- Ctesias. History of Persia

- Cornelius Nepos. Biographies of Miltiades and Themistocles

- Andreev Yu. V., Koshelenko G. A., Kuzishchin V. I., Marinovich L. P. Istoriya Drevnoi Grekii: Uchebnik [History of Ancient Greece: Textbook].

- Barry J. Smith Wars of Antiquity from the Greco-Persian Wars to the Fall of Rome, Moscow: Eksmo, 2009. ISBN 978-5-699-30727-2.

- Cambridge History of the Ancient World, vol. IV: Persia, Greece, and the Western Mediterranean ca. 525-479 BC, ed. by J. Boardman et al. Translated from English by A. V. Zaykova, Moscow: Ladomir, 2011, 1112 pages. ISBN 978-5-86218-496-9