Samnite Wars

The Samnite Wars were a series of armed conflicts between the Roman Republic and the Samnites.

The Samnites were an ancient Italic people speaking a language from the Oscan group, part of the Sabellian tribes. Initially, they lived in the mountains of Central Italy, south of Latium, bordering Campania and Apulia. This historical region became known as Samnium. Theodor Mommsen linked the origin of the Samnites to the Umbrians.

Samnite peoples

The entire Apennine mountain range, from the borders of Etruria to the southern tip of Italy, and some of the adjoining areas, were inhabited by several minor peoples. Most of them likely belonged to the same tribe, and thus they are often collectively called Samnites, after the most prominent among them. These included the Samnites, Sabines, Vestini, Marsi, Marrucini, Peligni, Hernici, Frentani, Hirpini, and Picentes. The Samnite peoples also included the Lucanians; the Bruttians, who occupied the southern tip of Italy in the 4th century BC, were formed from runaway mercenaries and slaves of various origins. The people inhabiting Campania during the existence of Rome arose from a mix of the earliest inhabitants of this land, the Ausones and Oscans, with the Samnites, who had taken Campania from the Etruscans.

The main occupations of the Samnites were agriculture and cattle breeding. In connection with them, as with the Latins, there was a religion and national holidays, the most famous of which were those that took place in Cures. Special priests, called fratres arvales, apart from performing their priestly duties, were engaged in agriculture, not only as a religious subject, but also as a scientific one. All the religious ceremonies and popular festivals of the Samnites were intended to maintain the government's control over the cultivation of the soil, and to excite the activity of the husbandman and preserve the ancient simplicity of manners by a sense of religious duty. The whole people, not excepting the noblest, cultivated the land with their own hands; and consequently agriculture was as highly cultivated among the Samnites as among the Latins. It is remarkable that agriculture, which, together with jurisprudence, formed the purely national science of the Italians, was one of the most important occupations of the inhabitants of Italy even in the most ancient times. The Romans even claimed that winemaking originated for the first time among one of the Samnite peoples – the Sabines. Cattle breeding was also carried to a high degree of perfection by the Samnites, and continued at this height throughout ancient history, so that even later Rome imported cattle, mules, and pigs mainly from the Samnite mountains. Agriculture was the common trade of the Samnites, and therefore there were very few cities in the country; the population was concentrated in numerous villages, and the few towns built in the most inaccessible places served only as shelters in case of enemy incursions. The industrious Samnites did not leave a single piece of land uncultivated in their mountainous country. The whole expanse of Monte Matese, now covered with snow for the greater part of the year, and left uncultivated since the time of the Samnites, thanks to the industry of that happy and industrious people, was converted into arable land or artificial meadows, and nourished an extremely dense population. These successes in economic development are easily explained by the simplicity of the Samnites ' manners and moderation, their innate love of work, and the internal connection of agriculture with all institutions and national life. Even the mountain forests were under the supervision of public authorities, as the Samnites were aware of their influence on the climate. The mountainous and well-cultivated region of the Samnites, which lay under the clear sky of Italy, combined all the advantages of the richest countries of nature; it is not surprising that Samnium was extremely densely populated, especially since, according to Samnite laws, uncultivated land was often distributed among the inhabitants for cultivation. An excessive increase in population could not be due to one ancient sacred custom. When it was necessary to fear a surplus of it, the celebration of the so-called sacred spring was appointed, consisting in a solemn vow to sacrifice or release all the cattle born in that year after twenty years, and to send all young people who had reached the age of twenty to settle in remote lands. Just as strange, but at the same time wise, were the Samnite rulings concerning marriages performed under the supervision of public authorities. At certain times, all the Samnite youths were gathered together, subjected to a thorough trial, and those who were found to be the best were given a free choice of brides; the rest of the wives were appointed by the public authority. Thus, Samnite marriage served as a means of encouraging young men to work, and on the other hand, all young men received wives who were supposed to help them in agricultural work and manage their household.

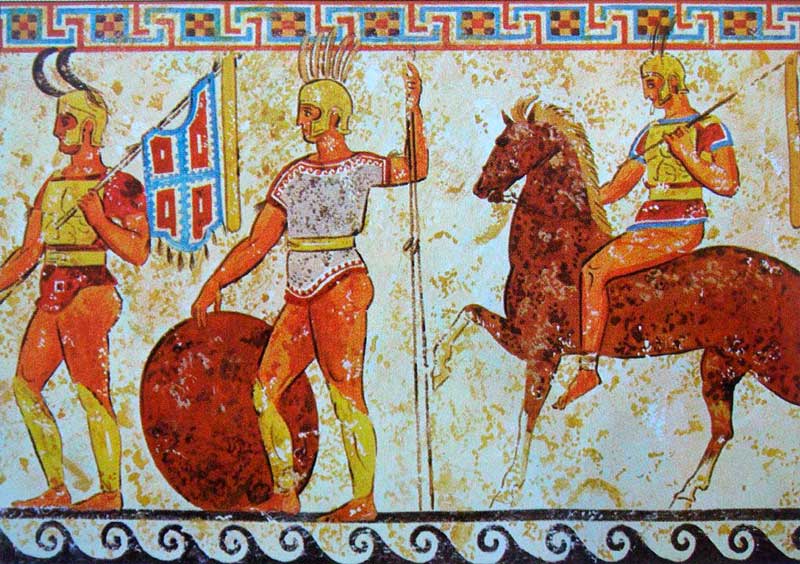

Fresco from the Fortress of Nola, Campania, 330-310 BC

Fresco from the Fortress of Nola, Campania, 330-310 BC

Ancient writers hardly mention the artworks of the simple and truly free Samnite people, and no colossal ruins like those left by the Etruscans are found throughout their homeland. However, the strict morals and spirit of moderation of the Samnites later influenced a specific direction in Roman literature. Among the Greeks, especially in cities of the Doric tribe or those with institutions based on Pythagoras' teachings, societal rules and descriptions of ancestral simple manners were passed on to the youth in verse. Similarly, from the Samnites, a code of strict moral conduct transitioned to the Romans, developing into a distinct form of poetry. The ancient Samnites, primarily the brave Sabines, who entered into close association with the Romans, brought them respect and influential power among other Italian peoples through their pure morals, religiosity, and justice. Even for later Romans, partly their descendants, the Samnites served as models of simplicity and honesty, so the expression "Sabine virtue" became proverbial and is often mentioned by Roman poets.

Among the Samnite communities or cantons, there was also a federative connection, in some ways quite similar to what we see with the Latins and Etruscans; however, this connection was never as weak as with the latter two tribes. The individual peoples into which the Samnite tribe was divided were almost completely unconnected with each other; the communities of each people formed special alliances, only occasionally including their fellow tribesmen. But even in this state of fragmentation, the energy of the Samnites and the strength of the bonds uniting the individual members of each people were fully evident. Despite their division, the Samnite peoples always offered fierce resistance to their external enemies.

The First Samnite War

In 343 BC, the Samnites resumed their devastating raids on Campania. Descending from the mountains, they began plundering the Sidicines living around Teanum, then proceeded from Tifata to plunder the Campanian plain, burning wealthy rural houses. The Campanians, unable to defend themselves, turned to the Romans for help. The Romans, according to tradition, initially refused to help, as they had recently made peace with the Samnites; however, the Campanians offered themselves under Roman protection. The Romans then demanded that the Samnites cease their war against a people under Rome's protection. The Samnites proudly rejected this demand and sent a stronger army to Campania. Both Roman consuls marched against them. Marcus Valerius Corvus, with one army, positioned near Cumae at Mount Gaurus, which was then covered with vineyards. His position was dangerous, and he could only escape by winning a victory. The Samnites attacked him; the battle was fierce, and both sides fought bravely: both Romans and Samnites resolved to give victory to the enemy only with their lives. Finally, the Romans won. The Samnites retreated to Suessula; they said the Romans' eyes burned, and their cheeks glowed with feverish heat. Another Roman army, due to the consul Aulus Cornelius Cossus' imprudence, fell into a very difficult position, having entered a narrow pass between Saticula and Beneventum, but was saved from destruction by the bravery of the military tribune Publius Decius Mus, who occupied a height commanding the entire pass with a select detachment and repelled the Samnites' attacks. The Senate and army rewarded Decius and his brave comrades with gifts and honors. Then both Roman armies united, and Valerius Corvus attacked the Samnites stationed at Suessula at the entrance to the Caudine Forks. After his previous victory, the Samnites who had retreated to Suessula received numerous reinforcements, but he attacked them in their camp and inflicted a terrible defeat on them; according to Roman chroniclers, the victors took 40,000 shields and 170 standards on the battlefield. Roman historians, glorifying the wars with the Samnites and Latins, tell many fictions; but these wars indeed laid the foundation for Roman dominance over Central and Southern Italy. Soon, the former Roman allies, the Latins, faced a threatening situation [340 BC]; therefore, they made peace with the Samnites, not demanding significant concessions, and formed an alliance with them. The Samnites paid the Roman army's annual salary and provided provisions for three months; in return, the Romans agreed not to interfere with their subjugation of the Sidicines.

The Second Samnite War

The Romans were spared the challenge of facing Macedonia at the peak of its power; instead, they fought a people just as brave but lacking unified leadership and a clear, determined strategy. The Samnites were fragmented and, despite their valiant efforts against Rome's overwhelming power, they did not receive strong support from their fellow tribes or the effete Greeks of Southern Italy. During their war with Alexander of Epirus, the Samnites ignored Campania, allowing the Romans to consolidate their control there by establishing colonies and distributing lands to Roman settlers. However, after Alexander's death eliminated the threat from the east, the Samnites sought to halt Roman expansion to the west.

The Romans founded the military colony of Fregellae on Volscian territory previously conquered by the Samnites, sparking conflict between the two peoples. This conflict was exacerbated when the Samnites and Tarentines, now allied, stationed troops in Naples—the only Greek city on the western coast still independent. These troops arrived in 327 BC, likely at the request of some Neapolitans seeking protection against Roman designs. Ignoring the Samnite-Tarentine garrison, the Romans demanded reparation from the Neapolitans for grievances at sea and in the Falernian fields. When refused, they besieged Naples. Internal discord soon arose between the Neapolitans and the garrison. During this siege, the Romans extended a commander's term beyond his elected period for the first time. The Neapolitans, dissatisfied with the disruption to their trade and offended by the garrison's arrogance, entered secret negotiations with the Romans and surrendered the city in 326 BC. In return, they received favorable alliance terms, including full equality and exemption from providing land troops to Rome. Soon after, the Lucanians joined the Roman alliance.

Alexander of Epirus, who fought the Lucanians, had some Lucanians in his army, indicating severe internal strife among them. These conflicts led the aristocratic Lucanians to ally with Rome. The Samnites' friendship with the Tarentines hindered Lucanian raids on Tarentine lands, fueling Lucanian resentment and their alliance with Rome. Rome also secured alliances with southern Sabellian cities like Nola, Herculaneum, Pompeii, and Nuceria, using the same tactics of courting local aristocrats as in Campania and Lucania. The isolated tribes—Marsians, Pelignians, Marrucinians, and the Samnite tribe Frentani—were granted grazing rights in neighboring Apulian mountains by Rome, which led them to agree not to aid Rome's enemies. The Vestini were forced into an alliance by Roman arms, while the Apulians, long suffering from Samnite raids, saw the Romans as their saviors.

Under these circumstances, the war went poorly for the Samnites. They bravely defended their valleys, passes, villages, and lightly fortified towns, fighting boldly on open fields. However, the Romans, confident in their strength and led by energetic yet cautious commanders, typically emerged victorious. After five exhausting years of unsuccessful warfare, the Samnites, losing hope, decided to surrender their bravest general, Papus Brutulus, to the Romans in 322 BC. Brutulus took his own life, and his body, along with Roman prisoners, was sent to Rome. Yet, these humiliating pleas did not soften Roman resolve. The Romans demanded the Samnites acknowledge Roman supremacy and provide troops. Unwilling to forfeit their independence or dishonor their past, the Samnites rallied under the noble warrior Gavius Pontius and sought aid from the Tarentines and Sabellian kin, while striving to strengthen their federation.

Rome soon regretted its intransigence. In 321 BC, consuls Spurius Postumius and Titus Veturius, hearing of a Samnite siege of Luceria, marched to its aid but fell into a trap at the Caudine Forks, surrounded by steep hills and cut off by enemy forces. Deceived by false intelligence, the Romans found themselves hemmed in. After heavy fighting, starvation and enemy arrows forced the consuls to seek mercy. Pontius reportedly faced conflicting advice from his father, Herennius, to either release the Romans unharmed to earn their gratitude or annihilate them. Choosing a middle path, Pontius demanded the Romans swear an oath to an equal alliance, abandon the colonies of Cales and Fregellae, and leave 600 knights as hostages. The humiliated Roman army passed under the yoke, stripped of weapons and possessions, and returned to Rome.

Rome plunged into mourning. Administrative and judicial activities halted, and a universal draft was called. The Senate annulled the treaty as unauthorized by the people's assembly, deeming the consuls' actions illegal and delivering them in chains to the Samnites. Pontius refused to accept the consuls, recognizing that doing so would legitimize the Roman claim that treaties bound only the signatories, not the state. He also spared the hostages. War resumed with renewed bitterness on both sides.

Roman allies reacted variably to the Caudine disaster. Luceria, Fregellae, and Satricum fell to the Samnites. Had Pontius pursued war immediately, Latin and Volscian revolts might have forced Rome to restart its conquests. However, Roman loyalty among allies revived, bolstered by the skilled general Papirius Cursor, who reversed the war's fortunes. Papirius swiftly marched to Apulia, joined forces with another consul, defeated the Samnites, and captured Luceria by starvation in 319 BC. The retrieval of Roman standards and the release of hostages restored Roman pride.

With the capture of strategic towns and suppression of revolts, Roman domination over Campania was cemented. Colonists settled deserted areas, military colonies were established, and strategic cities garrisoned. Appius Claudius built a grand military road from Rome to Capua, the Appian Way, solidifying Roman control and ambition to dominate Italy.

Clearer than ever, Rome's ambition to conquer Italy demanded a unified resistance from all independent states and tribes. Only concerted action could thwart Roman plans. Yet internal strife and short-sightedness, especially among the Tarentines, hindered effective resistance. Tarentum's wealth and fleet could have decisively influenced the war, but their inconsistent and self-indulgent policies alienated potential allies and provoked Rome without offering substantial support to the Samnites. Meanwhile, northern neighbors like the Etruscans rekindled their war with Rome in 311 BC by besieging Sutrium, forcing Rome to split its forces.

Despite setbacks, the Romans, led by commanders like Quintus Fabius Maximus Rullianus, turned the tide. Fabius' daring march through the Ciminian Forest and victory at the Vadimonian Lake in 310 BC ended major Etruscan resistance, while Papirius Cursor's victories in Samnium in 308 BC further cemented Roman dominance.

By now, Roman might seemed unstoppable. New enemies like the Umbrians and Hernici joined the fray too late, their strength insufficient against Rome's consolidated power. In 308 BC, the Umbrians were defeated, and the Marsi and Peligni subdued. Hernician revolts in 306 BC gave Rome a pretext to strip them of autonomy, imposing harsh terms and integrating their territories.

These victories sealed the fate of the Samnites. Even as they regained strength and captured cities like Sora and Calatia, the relentless Roman advance and the subjugation of rebellious allies like the Aequi signaled the end of Samnite resistance. The Second Samnite War firmly established Roman supremacy in central and southern Italy, laying the groundwork for further conquests and the eventual unification of the peninsula under Roman rule.

Third Samnite War

The peace with the Samnites lasted for six years (304-298 BC), and the Romans made extremely good use of this time to consolidate and expand their rule. Before the end of the war, the revolt of the Guernicians and Equians gave them an excuse to annex these peoples to their state, to take all their forces at their disposal, without giving the annexed peoples any political rights; now, taking advantage of the fall of some of the Volscian cities, they took from them several districts, which they added to their public land, sent new colonists to Arpin, Fregellae, Sora, and some other cities, built fortifications, and built military roads, so that the whole Volscian land was now connected with Rome by strong ties. Similarly, they also inextricably linked with Rome the areas that separated Samnium from Etruria and Umbria: they built military roads in these areas and put their garrisons on them.

Expansion of the Roman Republic

Expansion of the Roman Republic

The peace with the Samnites lasted six years (304–298 BCE); the Romans took full advantage of this time to consolidate and expand their power. Just before the end of the war, the rebellion of the Hernici and Aequi provided them with an excuse to annex these peoples into their state, taking control of all their forces without granting them political rights. Now, by taking advantage of the defection of some Volscian cities, they seized several districts from them, which they annexed to their public land, sending new colonists to Arpinum, Fregellae, Sora, and some other cities, building fortifications, and constructing military roads, so that the entire land of the Volscians was now firmly connected to Rome. Similarly, they tied the regions separating Samnium from Etruria and Umbria unbreakably to Rome by constructing military roads and stationing garrisons there.

The Romans built a new road through loyal Ocriculum to the city of Nequinum, situated at the confluence of the Nar and Tiber rivers. This city, once belonging to the Umbrians, was now made a Roman military colony and renamed Narnia. Between Samnium and Etruria, on the border of the Marsian territory, important military colonies, Carseoli and Alba, were founded and connected to Rome by military roads, thus cutting off communication routes between Samnium and Etruria. We have already discussed how the Romans carefully consolidated their power in Nar, Apulia, and Campania.

The Samnites viewed this expansion of Roman dominance and the establishment of fortified colonies, which acted as military outposts solidifying the subjugation of conquered lands and preparing paths for new conquests, with alarm. These colonies were clearly intended to divide central Italy into two halves. The Samnites decided to test their military luck once more before the enemies completely Romanized the regions surrounding Samnium and cut it off from any connections with Etruria and Campania. Roman aggressions and their ambition caused unrest everywhere, manifesting in various uprisings, making circumstances seem favorable for starting a war. The Samnites could not wait quietly for Rome to subdue all opponents, complete their preparations for conquering Samnium, and then force them to live as shepherds in unfortified settlements, forbidden to descend from their mountain pastures. The Samnites entered into negotiations with the Lucanians, persuaded them to defect from Rome, and formed an alliance with them, leading to the Third Samnite War in 298 BCE. In Lucania, a party loyal to Rome requested help, and the Romans sent one army to Lucania and another to Samnium. The consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Barbatus, who marched against the Lucanians, forced them to sue for peace and give hostages, as described in the inscription on his tomb found last century. Thus, the war with the Lucanians ended with a single campaign in 297 BCE. Victories were also achieved in Samnium by Fabius Maximus Rullianus at Tifernum and Publius Decius Mus at Maleventum. However, the Samnites unexpectedly turned the tide of the war with a bold expedition: they sent the brave Gellius Egnatius with a large army to Etruria to incite the discontented Etruscans to revolt, summon the Gauls from northern Italy, and with combined forces, march against the Romans.

The appearance of the Samnites in Etruria caused a general uprising in 296 BCE, threatening to nullify all of Rome's previous victories. The Etruscans and Umbrians joined the Samnites and summoned many Gallic mercenaries. The name of the Gauls still frightened the Romans; they redoubled their efforts to combat the numerous enemies. All citizens capable of marching, including many elderly family men, were taken into the army; freedmen were enlisted, and forces were demanded from allies. Consequently, the Romans sent such strong forces against all their enemies that they triumphed everywhere. One of their armies protected Campania and ravaged Samnium, acting in such a way that its camp was guarded not so much by its fortifications as by the terror that made the entire population flee far from it. The greatest Roman generals of that time, Fabius Maximus Rullianus and Decius Mus, led the main army into Etruria; its rear was protected by two reserves, one stationed at Falerii and the other near Rome, on the Vatican Hill. The Roman vanguard was defeated, and the fleeing soldiers brought news to the main army that enemy forces were concentrated in Umbria; the army, numbering 60,000 soldiers, a third of whom were Roman citizens, with a numerous cavalry, marched there. Simultaneously, Gnaeus Fulvius led the detachment stationed at Falerii into Etruria to force the Etruscans to return to defend their own country. Indeed, a significant portion of the Etruscans left the allied army before the decisive battle.

On a hot summer day in 295 BCE, a bloody battle was fought at Sentinum, at the eastern foot of the Apennines, which was to decide the fate of Italy. One consul, Quintus Fabius, stood on the right wing against the Italians; the other, Publius Decius, on the left against the Gauls. The battle swayed for a long time. The Samnites held out bravely against Fabius's legions; Decius twice repelled the Gallic cavalry's attack, but the appearance of Celtic war chariots caused confusion and disorder in his ranks; retreat began to become general, and a heavy defeat loomed. At this moment, Publius Decius, following the example set by his father in the battle at Vesuvius, ordered the chief priest present to dedicate him as a sacrifice to the gods of the underworld. After the rite was performed, he exclaimed, "Before me are horror and flight, blood and death, the wrath of the celestial and infernal gods! From me, a deadly curse on the standards and weapons of the enemies! Where I fall, may destruction befall the Gauls and Samnites!" With these words, he spurred his horse and dashed into the thick of the enemy. He was killed, and from that moment, the course of the battle changed. The Gauls stood frozen around his body, while the Romans rallied to their leaders; the bravest rushed in Decius's footsteps to avenge him or die beside his body. A detachment sent by Fabius to aid the left wing, commanded by Lucius Cornelius Scipio, completed the victory. Attacking the Gauls from the flank, the onslaught of the Campanian cavalry drove them to flight; soon, the other enemy wing, consisting of Samnites and other Italians, also fled. They hurried to their camp, but Fabius cut off their path; the Samnite commander Gellius Egnatius fell at the camp gates, and the Romans stormed in. On the battlefield lay 9,000 Romans; the number of killed and captured enemies was three times greater. This defeat shattered the coalition. The Umbrians, Etruscans, and Senone Gauls bought peace by submitting to Rome; the Celtic mercenaries dispersed. Only the Samnites still showed courage: 5,000 of them remained; in an orderly manner, they retreated through Pelignian territory to their homeland. During Fabius's triumph, the soldiers sang simple songs about his victory and how Decius sacrificed himself for the fatherland.

The defeat at Sentinum crushed the power of the Samnites, but their courage and love of freedom remained unbroken. When Roman forces moved from pacified Etruria to the south, they encountered stubborn resistance from the Samnite army in Campania, despite the construction of two Roman coastal fortresses, Minturnae and Sinuessa, the previous year. The Roman commander Marcus Atilius was even defeated by the Samnites. But they had no allies. The Tarentines abandoned them, unwilling to send an army far from their city, which was threatened by the Lucanians and the powerful tyrant Agathocles. Left alone, the Samnites could not withstand the Romans for long. Their heroism was in vain: relentless fate had decided to place them under Rome's dominion. Even their last resort of seeking salvation in a religious ritual proved futile: gathering an army for inspection, they chose the bravest warriors, led them to an altar drenched in the blood of sacrificial animals, and there, 16,000 warriors in white linen garments swore an oath to prefer death to retreat, to kill any deserter or coward. At Aquilonia, this sacred band was defeated by legions led by Papirius Cursor, son of the famous general, and Spurius Carvilius. After that, the strongholds where the Samnites had stored their belongings were captured, looted, and burned. Papirius adorned the forum with the spoils, and Carvilius made a colossal bronze statue of Jupiter Capitolinus from his share of the loot; it was so huge that it could be seen from the Alban Hills.

But even the defeat at Aquilonia did not shake the Samnites' courage: with astonishing heroism, they continued to defend their mountains against numerous Roman forces for over two years, even achieving occasional victories. Finally, the old hero Fabius Maximus Rullianus marched against them, bringing the war to its conclusion. We do not know where the final battle was fought, but it resulted in the death of 20,000 Samnites, and 6,000 captives were soldinto slavery. Among the prisoners was the commander Gavius Pontius. Whether he was the same Pontius who had triumphed at Caudium or his son, it was nonetheless an ignoble act by the Romans to chain him, bring him to Rome, and execute him in prison. Now Samnium was completely exhausted; worn down by 37 years of warfare, the Samnites made peace with the consul Manius Curius Dentatus in 291 BCE, who also forced the Sabines to abandon their planned uprising and submit entirely to Rome. The Samnites recognized Roman supremacy and agreed to supply troops for Roman armies. The Romans treated them leniently to avoid provoking another war with harsh peace terms. Taking advantage of the ensuing calm, the Romans solidified their control over the conquered lands by establishing military colonies and defining precise legal relations with the vanquished.

In the Sabine territory, rich in olive oil and wine, the cities of Reate, Nursia, and Amiternum were placed under the administration of Roman prefects, and many plots of land were distributed to Roman settlers. Further north, along the coast, the fortress of Hadria was founded. During the war, fortresses like Minturnae and Sinuessa had been constructed in Campania; now, the settlers in these colonies were granted full Roman citizenship to secure their loyalty to Rome. Special efforts were made to consolidate control over the eastern coast. They sent 20,000 citizens as colonists to the Apulian city of Venusia, located at the border of Samnite, Lucanian, and Tarentine territories, turning this city into a stronghold of Roman power in the region.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Etruscans, Latins, Aequians, Samnite Warrior