Spartacus Uprising

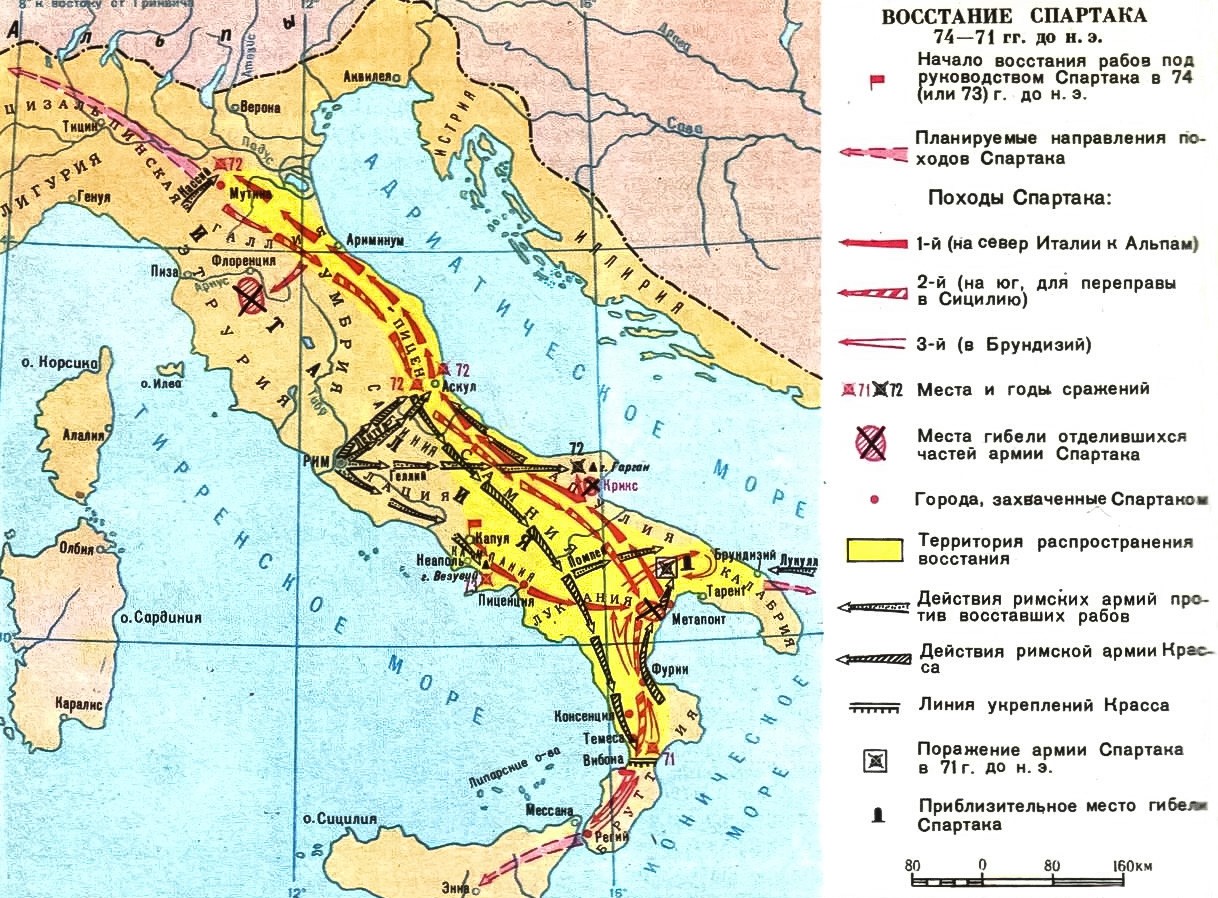

The Spartacus Uprising (Latin: Bellum Spartacium or Tertium Bellum Servile, "Third Servile War") was the largest slave rebellion in antiquity and the third in a series (following the First and Second Sicilian Uprisings). It was also the last slave uprising in the Roman Republic, typically dated to 74 (or 73)–71 BC.

Dates of the Uprising:: 74 or 73-71 BC.

Causes of the Uprising::

1. An excess of slaves due to Rome's conquests;

2. The lack of rights for slaves;

3. Harsh working and living conditions for slaves.

Objectives of the Rebellious Slaves::

1. A military march northward through Italy, to cross the Alps and gain freedom, allowing them to return home;

2. Some historians believe Spartacus intended to capture Rome itself, but this is not proven;

3. Armed resistance against Rome to avenge the suffering and humiliation they endured as Roman slaves;

4. Establishing connections with Sicily—toward the end of the uprising, after the reverse march from the north to the south of Italy, the aim was to establish a connection with Sicily and continue the rebellion there, living freely and independently from Roman rule;

5. Sharing all the looted wealth and property.

Leaders of the Rebellion: Thracian Spartacus; Gaul Crixus; Gaul Oenomaus; Celt Gannicus; Gaul Castus.

Roman Commanders: Praetor Gaius Claudius Glaber; Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Clodianus (consul); Marcus Licinius Crassus; Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (the Great); Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus.

Location of the Uprising: Italy. The rebellion began in central Italy and then spread to the north and south.

Reconstruction of the fresco from Pompeii "Wounded Spartacus," 1st century AD.

Reconstruction of the fresco from Pompeii "Wounded Spartacus," 1st century AD.

Key Events

The uprising began in the city of Capua, at a gladiator school owned by Lentulus Batiatus. According to V.A. Goroncharovsky (The Spartacus War: Rebellious Slaves Against Roman Legions. St. Petersburg Oriental Studies, 2011, 176 pages), the rebellion began at the end of February 73 BC.

The gladiators had planned the uprising in advance, but it was revealed to the authorities by a traitor, forcing the rebels to act quickly. Seventy-eight men revolted at Batiatus's gladiator school, overpowered the guards, and escaped into the streets of Capua. Along the way, they seized a caravan carrying weapons for the gladiators from Capua to another city. Breaking through the city gates, the rebels established a camp on the summit of the dormant Mount Vesuvius. An attempt by local Roman forces in Capua to suppress the rebellion in its infancy failed, with several city cohorts sent to Vesuvius being defeated, leaving the rebels with even more weapons.

On Vesuvius, the rebels elected three leaders: Spartacus as the primary leader, and his Gallic assistants, Crixus and Oenomaus. Historians still debate Spartacus's ethnicity, as the term "Thracian" could refer to either a person from Thrace or a type of gladiator. The prevailing theory is that Spartacus was a warrior who had served in the Roman army but was sold into slavery after disobeying orders, where he became a gladiator.

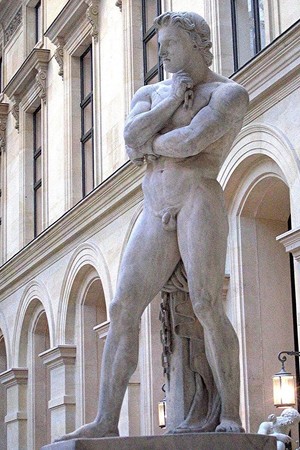

Relief with gladiators. Marble. Pompeii, Stabian Gate. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. 20-50 AD.

Relief with gladiators. Marble. Pompeii, Stabian Gate. National Archaeological Museum, Naples. 20-50 AD.

His forces raided nearby Roman villas and estates, causing his army to grow in numbers. Spartacus's army was large but ethnically and nationally diverse, comprising Gauls, Germans, Thracians, and other peoples enslaved by Rome. The army also absorbed shepherd slaves. This created a large but unreliable force, as most were agricultural slaves who had never held weapons. The core of Spartacus's army consisted of the 78 gladiators who had escaped with him from Capua.

Initially, the slave army was armed with sickles, pitchforks, rakes, and other agricultural tools, as well as clubs and sharpened stakes. Some slaves, skilled in basket weaving, made woven shields. Later, they acquired real weapons through battles. The main Roman forces were occupied outside Italy when the Spartacus uprising began. In 74 BC, Rome was at war with Mithridates in Asia Minor and was trying to suppress Quintus Sertorius, a supporter of Gaius Marius, who had raised a rebellion in Spain against supporters of Lucius Cornelius Sulla.

At first, the authorities and the Senate did not view the Spartacus uprising as a significant armed rebellion but merely a minor slave revolt leading to a wave of looting and violence in Campania (a region in southern Italy). However, as the scale of the rebellion became apparent, the Senate sent a substantial force of 3,000 men under Praetor Claudius Glaber in 73 BC. According to Appian, this force was not organized as a legion but rather as a militia of non-citizens, "gathered hastily and at random." (Appian. Civil Wars. 1.116). Glaber besieged the rebels on Vesuvius, blocking the only descent from the mountain, intending to starve them into submission. However, the rebels managed to fashion ropes and cords from the grapevines and trees growing on Vesuvius, using them to descend the mountain on the opposite side. They then circled around Vesuvius and attacked the Roman detachment, which was not expecting an assault from that direction, completely annihilating it. In this battle, Spartacus demonstrated one of his military tactics: to attack the enemy where and when they least expect it. However, Oenomaus was killed in this battle. After this, the rebels descended the mountain and occupied the former Roman camp, where slaves and others discontented with Roman rule began to join them.

The Course of the Military Campaign

The Course of the Military Campaign

In response, the Senate sent another force led by Praetor Publius Varinius. Varinius decided to divide his forces to encircle and "crush" the rebels. However, both of Varinius's detachments, under the command of his officers Furius and Cossinius, were defeated by the rebels individually. Varinius, with his remaining forces (about 4,000 men despite some desertions), fortified a camp near the rebels and attempted to blockade them. However, Spartacus broke through the blockade and moved towards the city of Cumae, with Varinius following, hoping to defeat Spartacus and recruit volunteers from Cumae. In the ensuing Battle of Cumae, Spartacus destroyed Varinius's forces, nearly capturing him. After this, almost all of southern Italy fell into the rebels' hands. Spartacus and his followers spent the winter of 73-72 BC near the city of Metapontum (an ancient Greek colony in southern Italy, now ruins near the town of Metaponto, Italy), where they trained their army. By winter 73-72 BC, Spartacus's army had grown to about 70,000 men.

In the spring of 72 BC, the rebels moved north towards Cisalpine Gaul (a Roman province located between the Alps, the Apennines, and the Rubicon. It was also known as Nearer Gaul or Gallia Togata). The Senate, recognizing the scale of the threat and the defeats of Praetors Glaber and Varinius, sent two armies, totaling 30,000 men, led by consuls Lucius Gellius Publicola and Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus. The consuls planned to encircle and crush Spartacus near the Gargano Peninsula. Lentulus's army advanced along the Via Tiburtina towards the Adriatic coast, while Gellius's army marched along the Via Appia to Apulia (a region in southeastern Italy).

To avoid encirclement, Spartacus sent his main forces northwest, while dispatching a large detachment under Crixus to the slopes of Mount Garganus (an isolated mountain massif in Italy's Foggia province, Apulia region, located on the Gargano Peninsula, the "spur" of Italy's boot, extending into the Adriatic Sea). Crixus's position was east of the road where Gellius's army was supposed to pass, posing a threat to its rear and right flank. If Crixus's detachment succeeded, Spartacus could then attack Lentulus's army from both sides. While Crixus held up Gellius's army, Spartacus unexpectedly attacked Lentulus's army, which had not yet completed its crossing of the Apennines, near the Aterno River (a river in Italy), defeating it decisively in two battles. Meanwhile, Gellius's army engaged Crixus's forces at Mount Garganus and annihilated them. Crixus himself was killed by the Roman praetor Quintus Arrius in this battle. Ancient authors (Appian and Livy) estimate Crixus's force at 30,000 to 20,000 men. After this, the ancient sources (primarily Appian and Plutarch) offer some discrepancies in their accounts, but with the appearance of Marcus Crassus, their information aligns again. While Appian and Plutarch differ in details, the overall course of events and Spartacus's actions, based on their accounts, can be summarized as follows: Spartacus, upon learning of Crixus's defeat, attacked Gellius's army and defeated it, after which both consuls were recalled to Rome.

During this time, Spartacus's army moved north but then, for unknown reasons, decided against crossing the Alps and headed south again, possibly hoping to reach Sicily, cross over to the island,and ignite another rebellion there, similar to the one that had been suppressed shortly before his own uprising. At this point, Spartacus's forces were estimated at between 60,000 and 120,000 men, though the latter figure is likely an exaggeration. On their return journey south, Spartacus's army bypassed Rome, causing widespread panic in the city. Thus, Spartacus once again reached southern Italy by early 71 BC. During this period, the Senate was desperately seeking someone capable of finally quelling the Spartacus uprising. Although the potential commanders Gnaeus Pompeius and Lucius Lucullus were considered, they were both occupied with wars outside of Italy—Pompeius in Spain against Sertorius and Lucullus in Asia Minor against Mithridates. Consequently, Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome's wealthiest and most influential figures, took the stage. His military experience primarily stemmed from his involvement on Sulla's side during the civil war between Sulla and Marius in 82 BC.

Crassus was entrusted with command and given the position of praetor. His forces consisted of six newly recruited legions, funded by himself, along with the remnants of the armies of Consuls Gellius and Lentulus. In total, Crassus had around 40,000-50,000 men under his command. At the end of 72 BC, two battles took place between Crassus's forces and Spartacus's army. In the first battle, Crassus was victorious, but in the second, the forces of his legate Mummius were defeated. After Mummius's defeat, Crassus, in order to restore military discipline, implemented the long-unused but in this situation crucial punishment of decimation (the execution of every tenth soldier by lot), which successfully reinstated discipline in his army. After this, Crassus avoided large-scale battles with the rebel army, opting instead to wear them down. This strategy led to a series of victories for Crassus in the summer of 71 BC near the area of Furiis (in southern Italy).

In the autumn of 71 BC, Spartacus retreated to Messina (a city in Sicily) via Lucania (a region in southern Italy), located near the strait separating Italy from Sicily. Here, Spartacus made an agreement with Cilician pirates, who, for a substantial sum, promised to transport him and his army to Sicily so he could spark a new uprising and replenish his forces. It is unclear why, but the Cilicians did not fulfill their promise. There are several theories explaining this circumstance, but the exact reason remains unknown.

There are several possible explanations for this:

1. Weather conditions worsened, preventing the necessary fleet from reaching the shores of Messina.

2. Their benefactor, the Pontic king Mithridates VI Eupator, who was at war with Rome, forbade them from assisting, as he needed to maintain a military threat to Rome within Italy itself.

3. They were bribed by the Romans.

4. Plutarch tells us that the pirates simply deceived Spartacus and his men.

While Spartacus awaited assistance from the pirates, Crassus decided to "trap" him on the small Rhegium Peninsula in southern Italy by constructing a deep ditch along the entire length of the isthmus (about 55 km), on top of which the Romans built a defensive wall or rampart. Crassus's plan succeeded. Deceived by the pirates and cut off from the rest of Italy by the ditch, a large number of people crowded into a small area, leading to famine among the rebels. However, Spartacus, after losing many of his followers, managed to break through the defensive wall on a winter night and escape the trap. At this time, after successfully suppressing Sertorius, Pompey returned to Italy with his troops and was ordered by the Senate to head south to assist Crassus. Historians disagree on whether Crassus requested help from the Senate or if they simply took advantage of Pompey's return to Italy. Lucius Lucullus's brother, the proconsul of Macedonia, Marcus Terentius Varro Lucullus, also received orders from the Senate to assist Crassus. Appian mistakenly believed that these forces were commanded by Lucius Lucullus himself, but he was actually in Asia Minor at the time, waging war against Mithridates. Fearing that his victory would be credited to other commanders, Crassus pursued Spartacus, who, after breaking through the defensive wall, headed towards Brundisium, possibly intending to cross from there to the Balkan Peninsula. However, at the approaches to Brundisium, Spartacus was met by Varro Lucullus's troops. Without engaging in battle, Spartacus began to retreat. During his retreat, a large detachment of 12,000 men, led by Gannicus and Castus, split off and camped by the Lucanian Lake. Crassus arrived there and, after a fierce battle, defeated this detachment. The remnants of this group withdrew to Spartacus and retreated with him to the Petelian Mountains (modern Strongoli) in Bruttium. The Roman forces closely pursued them. During the retreat, Spartacus managed to defeat the legate Lucius Quintius and the quaestor Tremellius Scrofa, wounding the latter in a battle on the river Casuentus. After this, he continued his retreat, realizing that in a decisive battle with Crassus, he and his men would be defeated. However, Spartacus's men insisted on a decisive battle with Crassus.

The final battle between Crassus's forces and Spartacus's army took place near the sources of the River Silarus (now the Sele River in southern Italy). In this decisive battle, Crassus emerged victorious, and although the ultimate fate of Spartacus remains unknown, he likely perished in this battle. However, his body was never found. Ancient authors, acknowledging Spartacus's bravery and courage, describe his death in the battle as follows:

Appian reports: "Spartacus was wounded in the thigh by a spear; kneeling on one knee and holding his shield in front of him, he defended himself from his attackers until he was finally surrounded and killed with a large number of his followers around him" (Appian, Civil Wars 1.120).

Plutarch reports: "...before the battle began, a horse was brought to him, but he drew his sword and killed it, saying that if he won, he would have many fine horses from the enemy, and if he lost, he would not need his own. With these words, he charged directly at Crassus; neither the enemy's weapons nor his wounds could stop him, yet he could not reach Crassus, though he did kill two centurions who confronted him. Finally, abandoned by his companions who fled the battlefield, surrounded by enemies, he fell under their blows, not retreating a single step and fighting to the end" (Plutarch, Crassus 11).

Florus writes: "Spartacus, fighting bravely in the front ranks, fell like a general."

Artist: F.A. Bronnikov. Painting: "Cursed Field." 1878. State Tretyakov Gallery.

Artist: F.A. Bronnikov. Painting: "Cursed Field." 1878. State Tretyakov Gallery.

Results and Consequences

The uprising of Spartacus and his supporters was crushed. As Appian reports, "Over 6,000 prisoners were crucified along the road from Capua to Rome" (Appian, Civil Wars Book 1, par. 120). Pompey claimed credit for ending Spartacus's uprising, as his soldiers defeated a 6,000-strong group of slaves who were retreating north after the Battle of Silarus.

Pompey reported to the Senate: "Crassus conquered the fugitives in open battle, but I have uprooted the very cause of the war" (Plutarch, Crassus 11).

This report from Pompey to the Senate further strained the already tense relations between Crassus and Pompey. In the end, the Senate acknowledged that Crassus had defeated Spartacus but denied him a triumph for his victory over Spartacus, citing the fact that the opponent was not worthy, as they were slaves. Instead, Crassus was granted a minor triumph, an ovation. However, even after Spartacus's death, scattered groups of his supporters continued to operate in southern Italy for a long time. These groups were not fully suppressed until 62 BC. Nevertheless, the uprising led the Romans to somewhat moderate their exploitation of slaves.

Reasons for Defeat:

- Poor armament of the rebels and the imbalance of forces, as well as the superior training of the Roman troops;

- Spartacus lacked a clear plan of action;

- The betrayal by the pirates;

- Division among the rebels.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Slave Revolt in Sicily, Marcus Licinius Crassus, Gnaeus Pompey the Great, Gladiators

Literature

Ancient authors:

1. Appian. Roman history. Civil wars.

2. Lucius Annaeus Flor. Epitomes of Roman history.

3. Sextus Julius Frontinus. About military tricks.

4. Plutarch. Comparative biographies. Crassus, Pompey.

5. Sallust. History

6. Suetonius. The Lives of the 12 Caesars: Divine August.

7. Titus Livy. The history of Rome from the foundation of the city.

Contemporary authors:

1. S. L. Utchenko. Ancient Rome. Events. People. Ideas. Moscow. Nauka Publishing House. 1969

2. Basovskaya N. I. Spartak. Eternal symbol / / Man in the mirror of history. - Moscow, 20

Barry J. Smith Wars of Antiquity from the Greco-Persian Wars to the Fall of Rome, Moscow: Eksmo, 2009.

4. Valentinov A. Spartak — Moscow: Eksmo Publ., 2002.

5. Goroncharovsky V. A. Arena i krovo [Arena and blood]. Roman gladiators between life and death. - St. Petersburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie, 2009. - ("Militaria Antiqua, XIV").

6. Goroncharovsky V. A. Spartak's War: the risen slaves against the Roman legions. St. Petersburg: Peterburgskoe Vostokovedenie Publ., 2011, 176 p. (in Russian)

7. G. Delbrueck. History of military art. St. Petersburg, 1994, vol. 1.

8. Karyshkovsky P. O. The Rise of Spartak, Moscow, 2005.

9. Kovalev S. I. Istoriya Rima [History of Rome]. A course of lectures. - LSU, 1986.

10. Kovan R. Roman legionnaires 58 BC-69 AD-Moscow, 2005.

11. Leskov V. A. Spartak, Moscow: Molodaya gvardiya Publ., 1983, 383 p. (Zhizn prekraschnykh dyudey).

12. Makhlayuk A., Negin A. Roman Legions in battle, Moscow, 2009.

13. Mannix D. Going to death, Moscow, 1994.

14. Mishulin A.V. Spartak's Uprising — Moscow, 1936.

15. Fields N. The Rise of Spartacus. The Great War against Rome. 73-71 BC = Spartacus and the slave war 73-71 BC. A gladiator rebels against Rome. - Moscow: Eksmo, 2011. - 94 p. - (Great battles that changed the course of history).

16. Tarnovsky V. Gladiators — Moscow, 1998.

17. Utchenko S. L. Krizis i poblenie Rimskoy respubliki [Crisis and Fall of the Roman Republic], Moscow, 1965.

18. Utchenko S. L. The Rise of Spartak // Ancient Rome. Events. People. Ideas — Moscow, 1969.