Slavery in Greece

The ancient system of slave-based production, which facilitated the economic development of ancient civilization, also underpinned its cultural achievements.

Even in the prehistoric Homeric period, slavery was the norm. Victorious warriors would enslave prisoners of war, either selling them or releasing them for ransom. Maritime piracy was also closely linked with numerous instances of enslavement. During this era, most slaves were Greeks, captured in wars between Greek city-states, which influenced the attitudes of masters toward their slaves. Over time, the distance between free citizens and slaves began to grow, and the number of slaves gradually increased. It is quite likely that the ratio of free citizens to slaves was 1:3. In Athens, there were hardly any families, even very poor ones, that did not own at least one slave.

Background

In the 19th century, the classical work of French historian A. Wallon, "History of Slavery in the Ancient World" (1st ed. 1847, 2nd ed. 1879), stands out. This fundamental work remained the only systematic attempt to compile material on ancient slavery for a long time. Other scholars of the 19th century, like K. Bücher, emphasized the significance of slavery for the peoples of classical antiquity.

William Mitford, in highlighting the development of slavery, stressed that only a small minority in Greece could enjoy freedom.

In contrast to the 19th century, the 20th century saw the issue of the social structure of ancient society, particularly slavery, become a central focus of classical studies.

As M. Finley noted, ancient society viewed slavery as a natural and organic part of its existence. A. I. Dovatur highlighted Aristotle's inclusion of the master-slave relationship among the primary human associations, alongside the marital couple. Aristotle, at the very beginning of his famous treatise "Politics," theoretically justified the necessity of slavery as a social institution, without which the "good life" of his compatriots would be impossible.

A. P. Medvedev underscores the role of the polis in maintaining the slaveholding character of ancient Greek society: according to Xenophon, all slave owners in the community acted together as a "voluntary guard"; Socrates’ discussion with Glaucon about the same topic is also well-known.

As Engels observed, "slavery alone made possible the division of labor on a more or less large scale between agriculture and industry and thereby enabled the flourishing of the ancient world, Greek culture. Without slavery, there would have been no Greek state, no Greek art and science; without slavery, there would have been no Roman Empire, and without the foundation of Greek culture and the Roman Empire, there would be no modern Europe. We must never forget that all our economic, political, and intellectual development had as its precondition a system in which slavery was as necessary as it was universally accepted."

E. Meyer, who argued that slavery was not much different from wage labor, and W. Westermann, who posited that slavery, serfdom, and wage labor were equally characteristic of ancient society, stand apart in the historiography of this issue, though their views are now outdated.

It is noted that historiography on the issue of slavery in the ancient world is closely linked with ideological differences in modern times.

Professor E. D. Frolov, discussing K. M. Kolobova's 1937 general survey of the economy of classical Greece, which he notes remains one of the best general overviews of the ancient world's economy, presents it as fully reflecting the concept developed by Soviet historians at that time, which regarded the slave-based mode of production as the defining systemic core of the ancient economy. This led to a "sharp rejection of the views of Ed. Meyer and M. I. Rostovtzeff, who saw no significant differences between the economic life of classical antiquity and the relations of the new, capitalist era, as well as the theory of K. Bücher, who reduced antiquity to the level of a primitive, self-sufficient economy without a developed exchange system."

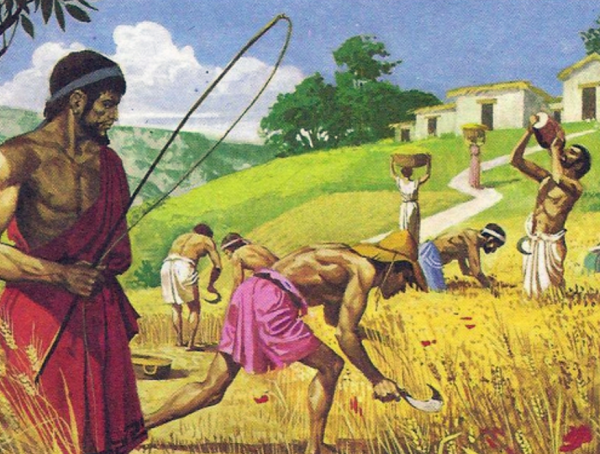

Illustration of Greek slaves working in the fields

Illustration of Greek slaves working in the fields

Sources of slavery

The sources of slavery in ancient Greece were generally the same as elsewhere: natural population growth, war, piracy, child abduction, the slave trade, the sale of children (a practice common everywhere except Athens), and the exposure of infants (allowed everywhere except Thebes). Additionally, debtors who were unable to repay their debts could be enslaved. The law also recognized as slaves those freedmen and metics who failed to fulfill their obligations to the state, as well as foreigners who fraudulently claimed citizenship rights.

Slaves were purchased from regions like Syria, Pontus, Phrygia, Lydia, Galatia, Paphlagonia, Thrace, Egypt, and Ethiopia. The most important markets for the slave trade were Cyprus, Samos, Ephesus, Chios, and Athens, with Delos eventually overshadowing them all. Every major city had its own slave market. During sales, merchants would try to present their slaves in the best light, highlighting their strengths and hiding their flaws, while buyers would carefully inspect them—turning them in all directions, undressing them, and making them walk, jump, and run. Certain flaws were well-known, and their presence allowed the buyer to return the slave to the seller.

The ancient author Athenaeus writes, "Ctesicles, in the third book of Chronicles, says that during the 117th Olympiad in Athens, Demetrius of Phaleron conducted a census in Attica and found there were 21,000 Athenians, 10,000 metics, and 400,000 slaves." This census is dated between 312 and 308 BCE. However, some scholars, starting with Hume, have been skeptical of Athenaeus's report of 400,000 slaves in Athens.

Conversely, August Böckh, based on data regarding the size of the Athenian army, estimated there were 84,000 citizens, 40,000 metics, and considered the overall slave population of Athens at 400,000 to be plausible. He based this estimate on the account by Hypereides of 150,000 slaves working in the silver mines, and he estimated the number of slaves outside Athens at 160,000–170,000, with 50,000 in Athens itself, giving a total of 200,000–220,000 adult male slaves. Including women and children, he considered the figure of 400,000 slaves to be quite reasonable.

Karl Julius Beloch, on the other hand, categorically disagreed with the figure of 400,000 slaves. Based on the calculated size of the Athenian army of 20,000–23,000 men and the ratio of military-age men to the total population, Beloch estimated the free male population of Athens in the autumn of 424 BCE at 30,000–35,000, and in 431 BCE at 40,000–47,000 (noting that a subsequent epidemic claimed a quarter of the population), with the total free population numbering between 120,000 and 140,000. He also noted that another 10,000 citizens were in cleruchies. Beloch criticized the reports of 400,000 slaves in Athens by comparing them to similar numbers of 470,000 slaves in Aegina and 460,000 in Corinth, arguing that neither Aegina nor Corinth had enough arable land to employ such a number of slaves, and that free men were hired as rowers on trading ships. He also disputed Böckh's assumption that 60,000 slaves worked in the Laurion mines, referencing Xenophon's desire to increase the number of slaves in Laurion to 10,000. Beloch thus suggested that there was a translation error, and the real figures were likely 70,000 slaves in Aegina, 60,000 in Corinth, and 40,000 adult male slaves in Athens, with a total slave population of 100,000. For the second half of the 4th century BCE, Beloch estimated the total slave population at 75,000, based on the number of medimnoi of grain produced in Attica and the amount of imported grain, concluding the total population of Athens at 175,000 people.

Eduard Meyer, based on the calculated size of the Athenian army in 431 BCE of 34,300 men (including 1,000 horsemen, 13,000 hoplites, 200 mounted archers, 1,600 foot archers, and 13,000 citizen-hoplites and 3,000 metics in the militia), and the known ratio of military-age men to the total population of 1/3, estimated the total free population of Athens at 170,000, with 42,000 metics. However, he considered it impossible to accurately determine the number of slaves in Athens but, based on Thucydides' report of 20,000 slaves fleeing to Decelea, he estimated the maximum possible number of slaves at 150,000.

R. L. Sargent attempted to estimate the number of slaves by different categories. She first estimated the free population, suggesting that under Demetrius of Phaleron, Athens had 90,000–100,000 free inhabitants, and on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, 208,500 people. Based on the ratios of different classes and the known number of slaves in households before the Peloponnesian War, she estimated the total number of domestic slaves at 30,500, dropping to 9,000–10,000 after the war. For agriculture, she estimated 10,000–12,000 slaves in the 5th–4th centuries BCE, based on 150,000 acres of arable land in Attica (1/4 of its territory). She estimated the number of slaves in the Laurion mines at 20,000 in 430 BCE. She criticized Wallon, who attributed 3 slaves to each citizen and metic, adding 10,000 for the mines and 101,000 in other sectors, reaching a total of 207,000 slaves in Athens in the 5th–4th centuries BCE. Sargent estimated that there were 22 artisan slaves in an average wealthy household, and suggested that the number of slaves in an average family was one person, though there were disagreements about the number of wealthy and poor families. She estimated the number of artisan slaves before the Peloponnesian War at no more than 28,000–30,000, with a more likely figure of 18,000–20,000. Based on an analysis of the known number of slaves owned by masters of different social groups, she estimated the total number of slaves in workshops and mines at 45,000–50,000 about 25–50 years before the Sicilian disaster, dropping to 20,000 after the disaster, and rising to 35,000–40,000 in the second half of the 4th century BCE. There is even less information about state-owned slaves: there were reportedly 700 slaves serving public officials (though Sargent considers this number exaggerated), 1,200 Scythian archers, 1,000–1,200 policemen (again, Sargent believes these figures are inflated), and slaves for public works (whose numbers are unknown). Overall, due to economic considerations, there was a surplus of adult male slaves over women, with the number of children and natural population growth being small (though possibly higher in rural areas than in the city). Thus, for the 5th century, the total number of slaves is estimated at 71,000–91,000, with women making up less than 1/5 of this figure—about 16,200–18,200—and children under 9 years old about 9,000–10,000 (9,720–10,920). According to Sargent, the number of slaves in Athens under Pericles was half that of the free population.

Gomme suggested that in 425 BCE there were 16,500 citizens of hoplite and equestrian census aged 18–60 years, and possibly 4,000 metics of the same census, but acknowledged the impossibility of accurately estimating the number of thetes and criticized Eduard Meyer's conjectural estimates of the proportion of thetes among rowers. Gomme turned to three sources on the number of slaves. According to Thucydides, more than 20,000 slaves, mostly artisans, fled from Attica to Decelea during the Decelean War. After the defeat at Chaeronea, Hyperides proposed arming all adult male slaves, numbering 150,000, but Gomme considered this number unreliable. Finally, Athenaeus's report of 400,000 slaves in Athens would imply 13 slaves per free resident in 313 BCE—an absolutely incredible number for a city where a workshop with 20 slaves was considered large, and a master with 45 slaves was considered wealthy. Based on the consumption of local (410,000 medimnoi) and imported (1,200,000 medimnoi) grain, Gomme estimated the total population of Attica in the 4th century BCE at about 270,000. He also estimated the number of male slaves in Attica in the 5th century CE at a maximum of 85,000 (50,000 employed in industry, including over 10,000 slaves in the Laurion mines in the 5th century according to Xenophon, and 35,000 servants), to which he added 35,000–40,000 female slaves. In Gomme's view, the number of slaves fluctuated depending on economic demand: there were fewer slaves in 480 BCE than in 430 BCE, more in 338 BCE than in 313 BCE.

Westerman also finds Athenaeus 'account of 400,000 slaves in ancient Athens unreliable, and is more inclined to trust Thucydides' account of 20,000 slaves fleeing to Dhekelia. According to him, slaves in ancient Athens made up from 1/4 to 1/3 of the population. In his opinion, the number of slaves in contrast to the free population fluctuated sharply, and in Attica increased in the era of Pentecontaetia (479-431), and the slaves themselves were used mainly in small-scale handicraft production, the demand for products of which determined the number of slaves (in his opinion, handicraft work was unpopular among the free population).

Status of Slaves

It is noted that in Ancient Greece, slavery was primarily integrated into artisanal production (in large workshops, up to 50-100 slaves worked) and mining (for example, on the Laurium silver mines, individual private owners used the labor of 300-1000 slaves), but in agriculture, the use of slave labor played a relatively minor and auxiliary role. In Attica, slaves made up about one-third (approximately 33-35%) of the entire population.

Slaves served as household servants: they managed the household, served at the table, and formed a personal entourage—which, however, was small (1-3 slaves), and they often replaced guard dogs. They were also engaged in crafts and trades in both the city and the countryside. Many slaves lived separately from their masters, independently practicing crafts and paying a fixed rent (Greek: ἄποροφά), while the rest of their earnings remained in their hands. In Athens, some slaves managed to amass quite substantial fortunes, and their ostentation and extravagance even led to complaints and criticisms. There were speculators who either exploited their slaves themselves or rented them out for various purposes. The profitability of slaves varied depending on their craft: for instance, slaves in Demosthenes' father's workshop, who made swords, brought in 30 minas annually (with their value being 190 minas); Timarchus' tanners earned 2 obols a day; and Nicias paid 1 obol a day for each of his mining slaves. Slaves served as rowers and sailors in the navy, and in extreme cases, they were sometimes enlisted in military service and could earn their freedom for bravery, with their owners being compensated by the state treasury.

A slave was considered the property, the thing, of his master; his personality played no role in the state, society, or family. Everything he acquired was considered the property of his master. The master also had the authority to permit or forbid marriages. Greek writers have left us descriptions of the cruel treatment of slaves. For example, in one of Aristophanes' comedies, we read: "Poor wretch, what happened to your skin? Didn’t a whole army of porcupines attack your waist and plow your back?" In "The Wasps," one slave exclaims: "Oh, turtle! How I envy the shell protecting your back!" In "The Frogs," there is the expression: "When our masters are keen on something, blows rain down on us." Starvation as punishment was common. For more serious offenses, they faced prison, whipping, rods, gallows, the breaking wheel. The fate of slaves working in workshops was even worse. Agricultural slaves were shackled, and the chains were not removed even during work. Leg irons, rings on hands, iron collars, and branding on the forehead—all these were not uncommon. Sicilian slave owners surpassed all others in their senseless cruelty. The master's care for the slaves was limited to the bare necessities: flour, wine lees, in some places fallen and overly salted olives—this was the diet of the slaves. Their clothing consisted of a piece of cloth turned into a belt, a short cloak, a woolen tunic, a cap made of dog skin, and rough footwear. Sicilian slave owners, unwilling to feed their slaves, allowed them to provide for themselves through theft and robbery, which reached enormous proportions here.

In Athens, the treatment of slaves was more humane, and their lives were more bearable than in other states. Xenophon speaks of the extraordinary "audacity" of Athenian slaves: they did not yield the road to citizens, and they could not be beaten for fear of striking a citizen instead of a slave, as the two were externally indistinguishable. In Athens, there was even a known ritual for introducing a slave into the family. Custom allowed him to have property (what in Rome was called peculium); wise masters, for their own benefit, rarely violated this custom. The same custom recognized a slave’s marriage as legitimate. On certain days, slaves were freed from their duties: in Athens, this occurred during the Anthesteria festival dedicated to Dionysus, when masters even served their slaves. A slave who fled to an altar or even merely touched sacred objects, like Apollo's laurel wreath, was considered inviolable, but masters sometimes forced him out of the temple with hunger or fire. According to custom, Athenian law also protected the slave: anyone guilty of insulting or killing another person’s slave was brought to trial and fined; a master could punish his own slave as he saw fit but was not allowed to kill him; if a slave killed his master, he was subject to a regular trial; a dissatisfied slave could demand to be sold to another master. Some of these reliefs existed separately in other Greek cities (peculium, marriage, festivals—in Sparta, Arcadia, Thessaly, etc.), but in Athens, they existed all together. Because of this, there were no slave revolts here. In other cities, slaves often rebelled. Nymphodorus tells of a successful slave uprising on the island of Chios, led by Drimakos. Both individuals and entire states made agreements regarding the extradition of runaway slaves.

With the master's consent, a slave could buy his freedom. A slave could also be freed by will. When manumission occurred during the master's life, it was announced in the courts, theaters, and other public places; in other cases, the slave’s name was entered into the citizen registers; sometimes freedom was granted through fictitious sale to a deity. Freedmen (Greek: ἀπελεύθεροι) did not become entirely independent of their former masters and had to perform certain duties toward them; failing to fulfill these obligations could result in them being re-enslaved. After a freedman’s death, his property passed to his former master. A slave could also gain freedom from the state for military service or significant services, such as reporting a state crime.

In addition to private slaves, there were also public slaves (Greek: δημόσιοι), belonging to the city or the republic. They were in a much better position, could own property, and sometimes achieved significant wealth; outside their duties, they enjoyed almost complete freedom. Public slaves formed the police force of archers known as Σκύθαι, although not all of them were Scythians; their duties included maintaining order in public assemblies, courts, other public places, and during public works. Jailers, executioners, clerks, accountants, heralds, and others usually belonged to this class; there were also public slaves of pleasure, meaning residents of brothels. Temples also owned slaves known as hierodules: some served in the temple itself (singers and singers, flutists and trumpeters, dancers, sculptors, architects, etc.), while others were serfs. These hierodules were donated to temples by private individuals, out of piety or vanity.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Slaves, Slave Uprising in Sicily, Spartacus Revolt, Aristotle

Literature

- Slavery in Mycenaean and Homeric Greece Authors: Ya. A. Lenzman

- Wallon A. The history of slavery in the ancient world. Translated from French by S. P. Kondratiev, Moscow: Gospolitizdat, 1941, 664 p.

- Vasilevsky M. G., Lipovsky A. L., Turaev B. A. Rabstvo // Encyclopedia of Brockhaus and Efron : in 86 volumes (82 volumes and 4 additions). - St. Petersburg, 1890-1907.

- Dovatur A. I. Slavery in Attica VI—V centuries B. E. L.: Nauka, 1980.