Political System of Republican Rome

The term "republic," traditionally used to describe the state and political organization of Rome from the 4th to 1st centuries BCE, does not inherently carry a qualitative meaning in its historical context (res publicae — "public affairs"). The Romans saw the purpose of their governmental organization as ensuring civil rights and guaranteeing special, privileged freedoms for full citizens of the city-state. The primary threat to civil freedom was considered to be the concentration of power in a single person or the executive authority (which is why past kings were often depicted with many vices in Rome's legendary history). Only the people as a whole held supreme power, delegating portions of it to different institutions and individuals. This principle became the foundation of the classical Roman Republic.

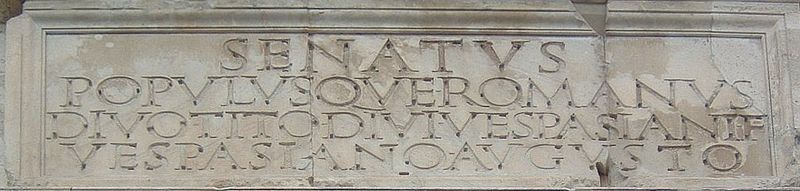

S.P.Q.R., an abbreviation of the Latin phrase "Senatus Populusque Romanus" ("The Senate and People of Rome"), was inscribed on the standards of Roman legions and used both during the Republic and the Empire.

Inscription on the arch of Titus (1st century AD)

Inscription on the arch of Titus (1st century AD)

1. General Concepts

The republican form of government was established in ancient Rome in 509 BCE, following the expulsion of King Tarquin the Proud.

The republican period is usually divided into the early and late republics. During this time, production developed intensively, leading to significant social shifts. The Roman Republic combined aristocratic and democratic features, which secured the privileged position of the wealthy elite of slave owners.

2. Social Structure

In Rome, full legal capacity was granted only to those possessing three statuses:

- Freedom

- Citizenship

- Family In terms of freedom status, Rome's population was divided into the free and the enslaved. The free citizens were further split into two socio-economic groups:

- The wealthy elite of slave owners (landowners, merchants)

- Small producers (farmers and artisans), who made up the majority of society, along with the urban poor. Slaves were either owned by the state or individuals. During the Republic, they became the main exploited class. The primary source of slavery was prisoners of war, but by the end of the Republican period, self-sale into slavery had also become common.

Regardless of their role in production, slaves were considered the property of their owners and were viewed as part of their assets. The power of a master over a slave was unlimited. In terms of citizenship status, the free population of Rome was divided into citizens and foreigners (peregrines). Freedmen were also considered citizens but remained clients of their former owners and were restricted in rights.

Full legal capacity was only available to freeborn Roman citizens.

Peregrines were free inhabitants of the provinces — countries conquered by Rome outside of Italy — as well as free residents of foreign states. To protect their rights, they had to choose patrons, placing them in a status not different from that of clients. Peregrines were subject to taxation.

As economic differentiation increased, wealth became a more significant factor in determining the status of a Roman citizen. By the end of the 3rd to 2nd centuries BCE, privileged classes such as the nobiles and equites (knights) had emerged. The highest class, the nobiles, formed through the merger of the most noble and wealthy patrician families with the upper plebeians. The economic base of the nobility was large landownership. The class of equites consisted of the trading and financial elite and middle landowners.

Family status implied that only the heads of Roman families — the paterfamilias — enjoyed full political and civil rights. Other family members were considered under the authority of the paterfamilias.

Only a paterfamilias who was free and freeborn could be fully enfranchised.

In public law, full legal capacity meant the right to participate in the popular assembly and hold public office; in private law, it meant the right to enter into a Roman marriage and participate in property relations.

Map of the Roman Republic

Map of the Roman Republic

3. Government Structure

The highest governing bodies in the Roman Republic were the popular assemblies, the Senate, and the magistracies. There were three types of popular assemblies:

- Centuriate Assemblies

- Tribal Assemblies

- Curiate Assemblies

The centuriate assemblies played the most important role, ensuring that decisions were made by the dominant aristocratic and wealthy circles of slave owners. By the mid-3rd century BCE, with the expansion of the state and the increase in the number of free citizens, the structure of the assembly changed: each of the five classes of wealthy citizens began to contribute an equal number of centuries — 70 each — and the total number of centuries was increased to 373. The centuriate assembly was responsible for passing laws, electing the highest officials of the republic (consuls, praetors, censors), declaring war, and hearing appeals against death sentences.

The tribal assemblies were divided into plebeian and patrician-plebeian depending on the composition of the tribes. Their jurisdiction was limited. They elected lower officials (quaestors, aediles, etc.) and considered appeals against fines. Additionally, plebeian assemblies elected the plebeian tribune and, starting from the 3rd century BCE, gained the right to pass laws, increasing their significance in Rome's political life.

The curiate assemblies lost their importance, eventually only ceremonially confirming officials elected by other assemblies, and were later replaced by an assembly of thirty representatives of the curiae — the lictores. The Senate played a truly crucial role in the governmental system of the Roman Republic. Every five years, censors (special officials who distributed citizens into centuriae and tribus) compiled the lists of senators from the ranks of the noble and wealthy families. Thus, senators were appointed rather than elected, making the Senate independent of the will of the majority of free citizens. Although the Senate was formally an advisory body, its functions included:

- Legislative: The Senate controlled the legislative activity of the centuriate and plebeian assemblies, approving their decisions and later pre-examining proposed laws.

- Financial: The state treasury was under Senate control; it set taxes and determined necessary expenditures.

- Public safety, urban development, and religious matters.

- Foreign policy: While war was declared by the centuriate assembly, peace treaties and alliances were approved by the Senate. The Senate also authorized military recruitment and assigned legions to commanders.

Public offices were known as magistracies and were divided into:

- Ordinary (regular) magistracies, including positions like consuls, praetors, censors, quaestors, aediles, and others.

- Extraordinary magistracies, created under exceptional circumstances such as severe wars, slave uprisings, or serious internal unrest. In such cases, the Senate could establish a dictatorship.

A dictator was appointed by one of the consuls upon the Senate's proposal. The dictator wielded absolute power, to which all other magistrates were subordinate. The term of dictatorship was not to exceed six months. Magistracies were filled according to the following principles:

- Elective: All magistrates, except the dictator, were elected by the centuriate or tribal assemblies.

- Term limitation: One year (except for the dictator).

- Collegiality.

- Non-compensation.

- Accountability.

4. The Army

The army played a vital role in ancient Rome, as the state's foreign policy was characterized by nearly continuous warfare.

Even in the monarchical period, the general assembly of the Roman people was also a military assembly, serving as a review of Rome's military strength; it was structured and voted by divisions — curiate assemblies. Military service was mandatory for all citizens aged 18 to 60, both patricians and plebeians. However, a client could fulfill military duties instead of their patron.

During the Republic, when the Roman people were divided into wealth-based classes, each class provided a certain number of armed men, who were then organized into hundreds — centuries. The equites formed cavalry centuries, while the first, second, and third classes formed centuries of heavy infantry, and the fourth and fifth classes formed centuries of light infantry. The proletarii provided one unarmed century. The command of the army was entrusted by the Senate to one of the two consuls.

In 107 BCE, the consul Gaius Marius carried out a military reform, after which the army became a permanent professional organization. Military service for Roman citizens was restricted, and volunteer recruitment was introduced, with volunteers receiving arms and pay from the state. Legionaries were rewarded with a share of the military spoils, and veterans were granted land from confiscated and free territories. The army became an instrument of policy, a hired force maintained at the expense of conquered peoples.

5. The Fall of the Republic

The development of the slave-owning society led to the exacerbation of all its class and social contradictions. The most significant socio-economic and political event in Ancient Rome in the 2nd century BCE was the crisis of the city-state organization, where the old republican institutions, adapted to the needs of a small Roman community, proved inadequate in the new circumstances. The collapse of the Roman Republic was marked by the following major political events:

- Slave uprisings — two uprisings in Sicily (138 BCE and 104–99 BCE) and the uprising led by Spartacus (74–70 BCE).

- The struggle between small and large landownership, a widespread revolutionary movement among the rural plebeians that almost led to civil war, led by the Gracchi brothers, who attempted to carry out agrarian reform (20–30s of the 2nd century BCE).

- Allied War ((91–88 BCE), an Italic-wide uprising against Rome's authority, led to the era of dictatorships, first under Sulla and later under Caesar.

Related topics

Roman Republic, Rome, Lucius Cornelius Sulla, Gaius Julius Caesar, Slave Uprisings in Sicily, Spartacus' Uprising, Gracchi Brothers