Fabrics in antiquity

There is a considerable amount of information about the use of fabrics in antiquity, allowing us to create accurate depictions of the people living during that time. Much is known about dyes and trade connections, which enables us to assess the possibilities of fabric coloring. The "triad of sources" has also been preserved, including written and archaeological sources with visual representations, allowing for a precise characterization of fabric density, draping, weaving, and colors.

Material

The most common material for fabrics in antiquity was undoubtedly wool. Almost all findings have wool as the foundation of their weave, with sheep's wool being the most commonly used. It was the most practical and affordable material - it provided good insulation, was durable, and offered excellent protection against unfavorable weather conditions.

In second place for clothing was linen. It should be noted that linen is considered a more expensive material to produce today compared to wool. It was less durable but could produce a cooler and lighter fabric, which was especially beneficial in hot climates. Additionally, the fine texture of linen allowed for versatile draping of fabrics, which was highly valued by the Greeks and Romans. Linen was most common among the Hellenistic peoples in antiquity.

Silk was the rarest type of fabric and was rarely used in clothing, as it was an imported material purchased by Rome at exorbitant prices. The money needed to buy a silk garment could instead buy a decent villa with slaves at that time, so it was considered a great extravagance. Only the elite could afford such luxury, and even then, it was rare.

Weaving

The most common weaving technique in antiquity was plain weave, consisting of fabric fibers interlaced in a simple over-and-under pattern. However, other weaving techniques were known, such as twill and herringbone weaves, which were more prevalent in the northern provinces of Rome and among barbarian peoples (such as the Celts and Germans).

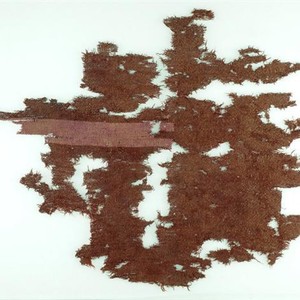

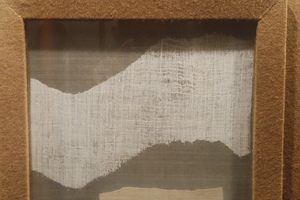

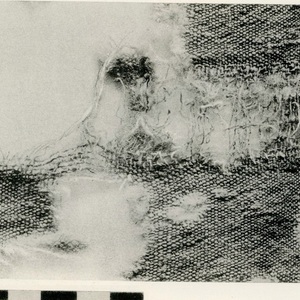

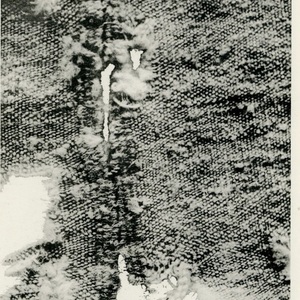

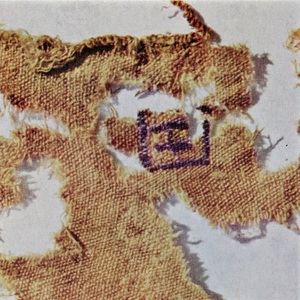

Examples of weaving Celtic fabrics

Examples of weaving Celtic fabrics

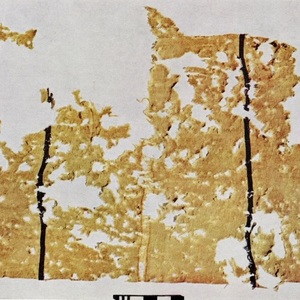

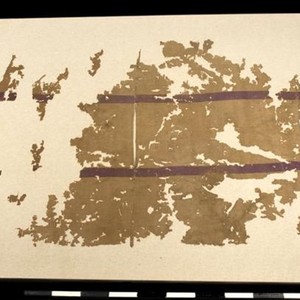

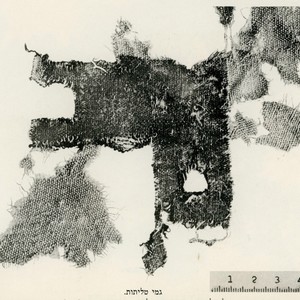

ne of the most valuable archaeological treasures of Roman textiles can be considered the mass findings in the Cave of Letters (Israel). The Cave of Letters (מערת האיגרות, Me'arat Ha'Igrot) is a cave located in Nahal Hever in the Judean Desert, where ancient texts were discovered, some of which are associated with the period of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt and are estimated to date back to the late 1st century and early 2nd century CE.

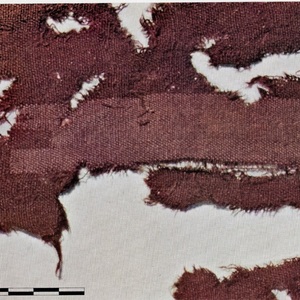

All the fabrics found there have a plain weave of wool fibers with varying densities and qualities. The main color palettes include colorless, yellow, cream, white, red, blue, and purple shades. Many of them have interwoven patterns of a different color (clavii and angles, as well as master's marks). The majority of recognized findings were tunics and cloaks. It should be noted that all samples had woven patterns, not sewn or embroidered ones. Below are samples from excavation No. 2.41-35. The edge is reinforced with a 3 (4 4 4) 5(8 4 4 4 2 2) braiding. The warp threads have a thickness of 8-10/1 and a density of 11/cm. The patterns have a denser structure, up to 20/cm. The edge treatment perpendicular to the warp threads is a parallel rope trim.

Fabrics from Egypt

Egypt held a special place in the ancient world of textiles. This ancient region maintained a leading position in both art and light textile production for a long time - during the era of the pharaohs, as part of the Greek state, and as part of the Roman Empire. This combination allowed Egypt to become a stronghold of the most expensive fabrics eagerly sought for export. One of the important reasons for the developed textile industry was the advanced technology of weaving looms. Egyptian fabrics were characterized by their thickness. Local artisans produced the finest fabric in the ancient world, and it was of the highest quality. Linen and wool scraps richly decorated with various patterns and motifs were frequently discovered. This quality also applied to wool and linen products, such as woolen socks, many of which were considered intricate work for that time. Another distinguishing feature of Egyptian textiles was the combination of fabrics made from different materials, most commonly wool and linen.

We know a lot about Egypt's industry thanks to its active trade connections with neighboring states (and later with neighboring regions within the Roman Empire), burial traditions (many useful artifacts were found in tombs), and, most importantly, the climate, which, along with Judea, preserved numerous fabric and leather items.

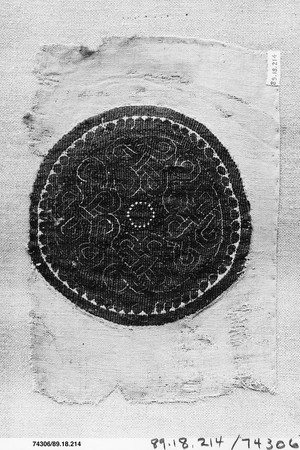

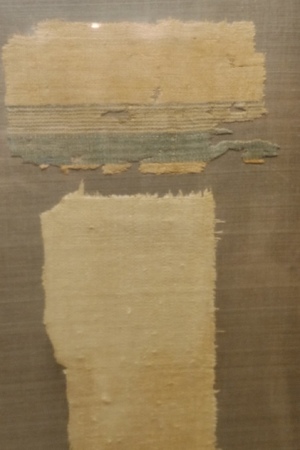

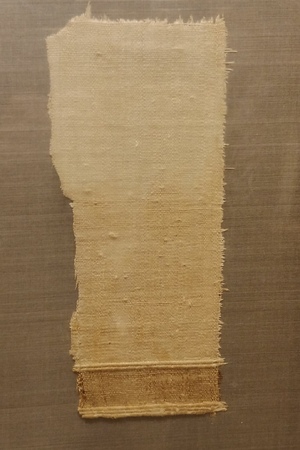

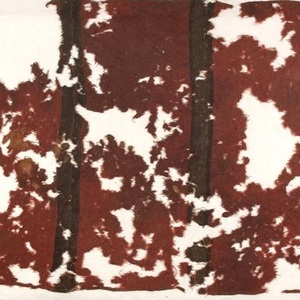

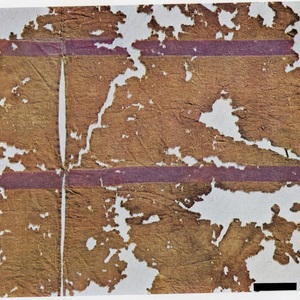

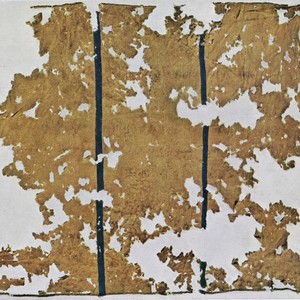

Fragments of segmental ornaments of Roman clothing from Egypt. Wool and flax. The size of the strips is 40*3.9 cm. The size of a rectangular fragment is 8 * 24 cm. The Walters Art Museum, inv. no. 83.485. 5th-6th century AD

Fragments of segmental ornaments of Roman clothing from Egypt. Wool and flax. The size of the strips is 40*3.9 cm. The size of a rectangular fragment is 8 * 24 cm. The Walters Art Museum, inv. no. 83.485. 5th-6th century ADDyeing

In antiquity, the dyeing of fabrics could vary significantly depending on the specific ethnicity. The Celts predominantly used shades of green, blue, and brick in their dyes, while the Romans and Greeks had a greater variety of colors that differed depending on social class. Today, many fabric findings in white/red and blue shades are known, most of which were discovered in Egypt, Judea, and northern parts of the Empire, such as modern-day Germany. This is due to the climate conditions where the fabric could be preserved exceptionally well.

Written sources

- The oldest source indicating the color of Roman tunics has a non-Roman origin. It is a Samnite fresco from the tomb of François, discovered near the ruins of the city of Vulci. It is believed to depict an episode from the Samnite Wars in 326 BCE. Titus Livius (IX, 40, 2-3 and 9) writes that some Samnites consecrated themselves and wore white linen tunics, as white was considered a sacred color. However, he does not mention the color of Roman tunics. In the fresco, we see warriors, both naked and dressed in white tunics, killing warriors in red tunics and bronze breastplates, who are assumed to be Romans or at least their Latin allies.

- The next source is a fresco from the Statiole tombs, depicting warriors in red tunics. Its dating is disputed, and some argue that it is a copy of an earlier work, so it can only be loosely associated with the Republican period.

- Next, the Palestinian mosaic should be mentioned, whose dating is also disputed, ranging from the end of the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE (supporters of the later dating consider it a copy of a mosaic from the Alexandrian School). However, historians agree that it depicts Octavian Augustus' visit to Egypt after the Battle of Actium in 31 BCE. The mosaic shows the Nile overflowing and flooding houses, and historians described the flooding that occurred at that time due to an exceptionally high flood of the Nile. In the central part of the mosaic, a group of warriors is depicted near a structure, possibly a temple. The central figure, wearing a white tunic and a muscular cuirass, is considered a general (possibly Agrippa). Some historians, however, believe that he is simply a warrior in a Greek chiton, boots, and a breastplate, as the entire scene is clearly executed in the Greek style. Next to him is a warrior in a red tunic with a typical knot on his neck, likely a Roman soldier or centurion. The bluish tint of his tunic suggests that the central figure may be Agrippa since Suetonius wrote that Augustus awarded him the right to carry a blue flag for his naval victories (Augustus, 25). Appian (V, 100) writes that a blue cloak was awarded for naval victories to Sextus Pompeius, and Vegetius (IV, 37) also mentions the blue color of sailors' tunics. By the way, the character on the far right, holding a horn, is considered to be Octavian, also dressed in the Greek manner. In the left part, we see warriors in white tunics. However, caution should be exercised in interpreting this fresco, as the warriors in clearly Greek equipment could have been copied from depictions of Macedonian warriors.

- The fresco "The Judgment of Solomon" from Pompeii, probably from the beginning of the 1st century CE. Some scholars consider it a copy of an earlier work from the Alexandrian School, which could depict Greek (Macedonian) warriors rather than Roman ones. Nevertheless, it is worth noting the red and white color of the warriors' tunics.

- Next is the drawing of a warrior in a white tunic and a yellow-brown cloak holding a pilum, from the signboard of a tavern in Pompeii. The pilum with its characteristic ball in the middle indicates that he is indeed a warrior.

- Furthermore, from the same Pompeii, there is an image of a warrior in a white tunic and a yellow-brown cloak, conversing with a woman.

- Isidore of Seville, referring to sources that have not reached us, wrote (Etymologies, XIX, xxii, 10) that during the time when the consuls ruled the Romans (presumably the Republican period), they had a dye called "russata," known to the Greeks as "phoenicea," and in Isidore's time (7th century), it was known as "coccina." According to him, the dye was invented by the Spartans, who used it to dye their tunics when going into battle, so that if they were wounded, the enemies would not notice the blood and be encouraged. From this, it can be concluded that the dye was red in color. Isidore writes that Roman soldiers also used it. Interestingly, Isidore states that this color was only used during battle, and before the battle, a flag of that color was hung in front of the commander's tent. This aligns with many descriptions from ancient sources (e.g., Caesar's "Gallic Wars," II, 4; Caesar's "Civil Wars," III, 89; Plutarch's "Pompey," 68). It is worth noting that the last two sources are particularly interesting as they describe the beginning of the Battle of Pharsalus. Caesar mentions a red flag, while Plutarch states that a red tunic was displayed.

- Quintilian (1st century AD), in his speech "For the Soldier against the Tribune," vividly describes the appearance of soldiers under Gaius Marius. He writes that they were armed with swords, solid armor, and helmets adorned with crests to intimidate the enemies. Their shields bore the name of Marius. At the end, he adds that they were dressed "in the garments of the god of war - Mars." Mars was depicted in Roman mosaics (for example, the mosaic in the Villa Borghese) wearing a red tunic, suggesting that Marius' soldiers were dressed similarly.

- Tacitus (Histories, II, 89), describing the triumph of Emperor Vitellius in Rome in 69 AD, mentions that the camp prefects, tribunes, and senior centurions were dressed in gleaming white tunics dedicated to Vesta. Some historians argue, based on how Tacitus emphasizes this, that whitened tunics may have been specifically used for celebrations. The mention of "tunics for the banquet" on the tablets from Windoland is also cited as an argument in favor of this view.

- Regarding the fabric fragments from Windoland, more than 50 samples were examined for the presence of dye. Only 9% of the cases showed the presence of dye. Out of these 9%, 8% were red, and 1% were purple (indicating a mixture of red and blue dye). 40% of the samples were white, and in the remaining 51%, either no pigments were present or they were too small to be identified. It's important to note that the fabric fragments were small in size, and it's unknown if they originated from tunics or whose tunics they might have belonged to. Additionally, traces of dye may have been lost due to poor preservation of these fragments. Therefore, conclusions from this study should be drawn with caution. The only thing that can be asserted is that among the fragments where dye was preserved, the majority were red (Taylor, 1983).

- The Gospel of Matthew states that the Roman soldiers who executed Christ wore red tunics.

- Martial, in his "Epigrams" (Book XIV, verse 129 "Red Cloaks from Canusium"), writes, "Romans prefer brown, while Gauls prefer red cloaks - a color that children and soldiers like." It is not entirely clear whether he refers to all soldiers.

- On the tombstone of Gnaeus Musius, an aquilifer of the 14th Legion (1st century AD), white dye was preserved on the tunic.

- Receipts for bill payments belonging to the legionary C. Messius, son of Gaius from the Fabian tribe, called to service in Beirut, were found near Masada in Israel (1st century AD). It is believed that he served in the 10th Legion, which we are reconstructing, and was a cavalryman. He paid 7 denarii for a linen tunic and an unknown amount for a white tunic made of an unidentified material. The linen tunic could have been used for ceremonial occasions or because it was more comfortable in a hot climate. This brings to mind a story described by Ammianus Marcellinus (XIX, 8.8) in which, allegedly, soldiers of the same 10th Legion tore their linen tunics into strips to draw water from a well in the 4th century. During excavations in Masada, a lot of linen fabric was found, but most of it likely belonged to defenders and residents of the city, and some may not have been clothing at all. The linen fragments were mainly undyed. However, out of 105 wool fragments, dye traces were found on more than half, including 14 in various shades of red, ranging from light to dark, and 6 light blue or blue-green ones.

Colorants

- Red

1) Madder - Rubia tinctorum. First appeared, presumably in Egypt, no later than 2000 BC. The active substance is alizarin, extracted from the roots with hot weakly alkaline solutions. Madder provides well-preserved coatings with metal oxides, slightly altering its shade.

2) Dyer's Alkanet - Alkanna tinctoria. First appeared, presumably in Egypt, no later than 3500 BC. The active substance is alkannin, extracted from the roots with hot weakly alkaline solutions. Iron and aluminum mordants can change the shades.

- Orange

1) Safflower - Carthamus tinctorius. It is believed to have originated in Egypt. The active substance is carthamin, which is extracted from the petals in weak alkaline solutions. It can dye without mordants, but the color is not very stable.

2) Henna - Lawsonia inermis. It is believed to have originated in Egypt, no later than 3000 BCE. The active substance is 2-hydroxy-1,4-naphthoquinone. The leaves are dried, ground, and the dye is extracted in a weak alkaline solution.

- Yellow

1) Saffron - Crocus sativus. Mesopotamia (?) - around 2000 BCE. The active substance is crocin, which is extracted with weak alkaline solutions.

2) Weld - Reseda luteola. Ancient Greece or Rome. The active substance is luteolin. It was most likely extracted with hot water. It could have been used together with an alum mordant.

3) Dyer's greenweed - Genista tinctoria. Presumably ancient Greece. The active substance is genistein glucoside. It was extracted with weak alkaline solutions or hot water.

4)Greater celandine - Chelidonium majus. Presumably ancient Greece. The active substance is chelidonine.

- Blue

1) Lichens - Rocella. Minoan civilization around 2000 BCE. The active substance is litmus. It was extracted with weak alkaline solutions.

2) Woad - Isatis tinctoria. It is believed to have originated in Egypt, no later than 2500 BCE. The active substance is indigotin. The leaves were ground with a small amount of water and the mixture was left to ferment in tall pots for about two weeks.

3) Indigo - Indigofera tinctoria. It is believed to have originated in India, no later than 2000 BCE. The active substance is indigotin. The leaves undergo fermentation, then they are vigorously stirred and an oxidizing agent is added.

- Purple

1) Murex - Bolinus brandaris. Phoenicia, the cities of Sidon and Tyre. The active substance is 6,6'-dibromoindigo. To extract the dye, the flesh of the mollusks was boiled. To intensify the color, the obtained mixture was exposed to the Sun or treated with acidic solutions.

2) Kermes - Coccus ilicis. One of the oldest dyes, from the Neolithic period. The active substance is kermesic acid. The dye is extracted with water, oxidizing agents, or weak alkaline solutions. Pre-mordanting greatly affects the color.

Related topics

Ancient Greece, Rome, Celts, Tunic, Ancient Egypt, Socks

Gallery

Gallery

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt

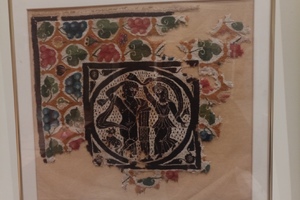

A piece of cloth depicting the earth goddess Gaia. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-11440. 3-4 centuries A.D.

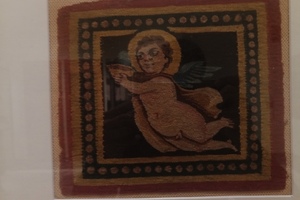

A piece of cloth depicting the earth goddess Gaia. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-11440. 3-4 centuries A.D. A piece of cloth with the image of Eros. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-13216. 4th century AD

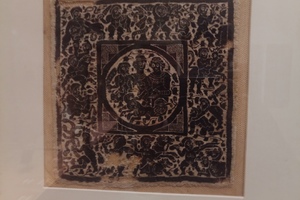

A piece of cloth with the image of Eros. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-13216. 4th century AD A piece of cloth depicting Dionysus, Ariandne and the twelve labors of Hercules. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-11337. 5th-6th centuries A.D.

A piece of cloth depicting Dionysus, Ariandne and the twelve labors of Hercules. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-11337. 5th-6th centuries A.D. A piece of cloth with an image of the Amazon. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-12959. 5th century AD

A piece of cloth with an image of the Amazon. Flax, wool. Egypt. Tapestry technique. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg. Inv. no. DV-12959. 5th century AD

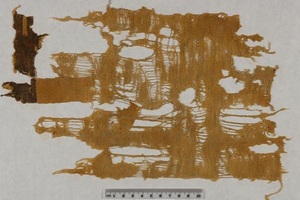

Cave of Letters

Cave of Letters