Helmets of the ancient Greeks

The history of the evolution of helmets in Ancient Greece dates back to the Mycenaean civilization in the mid-2nd millennium BCE. It is during this time that the earliest helmet finds and their depictions on frescoes are dated. In addition, there are written sources - Homer's "Iliad" describes the constructions of helmets worn by the heroes of the Trojan War (around 1200 BCE). This marks the beginning of the creation of various types of helmets. The earliest helmets found in Ancient Greece after the Trojan War are dated to the 9th century BCE. These helmets were mostly similar in shape to Assyrian helmets. From the 7th century BCE, craftsmen in Greece started producing fully enclosed helmets, which in the 6th century BCE acquired the most well-known form known as the Corinthian helmet. Corinthian helmets became one of the symbols of Ancient Greece and an essential attribute of hoplites in frescoes and ceramics. From the mid-5th century BCE, Corinthian helmets underwent modifications with the development of craft centers in Attica, Macedonia, southern Italy, and other places. New, more open types of helmets appeared (Boeotian, Chalcidian). With the beginning of Alexander the Great's conquests (in the 4th century BCE), the battlefields were primarily dominated by mass armies, for which more practical and standardized helmets were needed. By the start of Ancient Rome's expansion in the 2nd century BCE, the most common helmets were of the Thracian type, and since then, the development of armor has been closely tied to the evolution of Roman weaponry.

Types of Greek helmets:

- Prehistoric helmets (Archaic)

- Illyrian type (Illyrian)

- Corinthian or Doric type (Corinthian)

- Chalcidian type (Chalcidian)

- Attic type (Attic)

- Boeotian type (Boeotian)

- Phrygian type (Phrygian)

- Thracian type (Thracian)

- Pilos (Pilos)

Greek helmets from the museum in Olympia. 7th-6th century BC

Greek helmets from the museum in Olympia. 7th-6th century BC

Prehistoric helmets

In ancient times, the Greeks referred to helmets with a word that meant a cap made of dogskin - κυνέη (literally "dog-like"). In Homer's "Iliad," the word κυνέη denotes both a cap and any helmet, whether made of leather or metal, but without a visor, crest, or cheekpieces. Homer refers to copper helmets with cheekpieces and crests made of horsehair using the word κόρυς. The word κόρυς is etymologically related to the word κέρας, meaning "horn," and it is possible that helmets were called that due to the presence of horn-shaped decorations or crests.

Herodotus, describing the clothing and weapons of the Persian army, mentions fox-fur caps (helmets?) worn by Thracians. He also mentions leather helmets worn by other tribes. Therefore, such helmets were not exotic even in the early 5th century BCE. Caps made of felt, fur, and leather were reinforced with iron plates, bones, tusks, wood, or any other durable material that did not require special craftsmanship. Later, bronze plates that conformed to the shape of the head and covered a lining made of felt and leather were bent. The helmets of the heroes of the Trojan War, which were not made by the Greeks, significantly differed from those depicted by the Greeks on vases six centuries later and consisted of four plates.

Due to the primitive construction of composite helmets, only a few examples have survived from antiquity. The first all-metal helmets appeared in Greece in the 15th century BCE. The Heraklion Archaeological Museum in Crete houses a partially preserved bronze helmet with elongated cheekpieces and a pointed dome with a crest attachment for a horsehair plume.

After the Trojan War (around the 13th-12th centuries BCE), there was a migration of peoples. Greece entered the "Dark Ages," and the Greek tribes even lost their writing, let alone their craft skills. The first bronze helmets found in Greece from the 1st millennium BCE date back to the 8th century BCE and reproduce the shapes of Assyrian helmets with a rectangular face opening, wide triangular cheekpieces, a pointed dome, and a high crest with a decoration in the form of a bronze arc. These helmets are commonly referred to as conical helmets. After the disappearance of the crest and the smoothing of the dome into a hemispherical shape, the appearance of the helmet approaches the Illyrian type.

Illyrian type

Illyrian helmets were the first all-metal helmets produced in Ancient Greece after the "Dark Ages." Bronze sheets were curved to match the shape of the head, overlapped, and fastened with rivets at the points of contact, resulting in longitudinal ribs of stiffness on the top of the helmet. Later, the Greeks learned to forge helmets from a single piece, traditionally retaining the longitudinal ribs. Helmets of this type were mainly discovered in the region that was occupied by Illyria in ancient times, which gave this type its name.

A characteristic feature of this helmet is the absence of a visor, longitudinal ribs on the top, large triangular cheekpieces, and a rectangular face opening. If a massive visor is added, the neck is covered by an elongated rear part, and the "ears" (cheekpieces) are given a shaped form and bent around the face, the helmet evolves into the Corinthian type.

In the 7th century BCE, Illyrian helmets fell out of use in Greece, being supplanted by the development of Corinthian helmet craftsmanship. The Illyrian type continued to be used until the 5th century BCE in less technologically advanced Macedonia at that time. The period between 725-650 BCE is marked by the presence of 30 early conical helmets, an equal number of Illyrian helmets, and 17 Corinthian helmets. In later times, between 650-575 BCE, conical helmets disappear, the number of Illyrian helmets decreases to 7, while the number of Corinthian helmets reaches 90.

Corinthian Type

Corinthian helmets emerged in the 7th century BCE. They gained the greatest popularity in the 5th century BCE during the Greco-Persian Wars. By the end of the 5th century BCE, the Corinthian type was replaced by more convenient Chalcidian helmets. The Corinthian type was a fully enclosed helmet adorned with a crest made of horsehair. It provided complete protection for the head, but the visor and closed face limited visibility. Outside of combat, the helmet could be pushed back on the nape, uncovering the face. The Corinthian helmet is an essential attribute of a hoplite in the depictions on ancient Greek ceramics from the 6th century BCE, even if the warrior fights bareheaded. The appearance of this helmet is associated with the development of the phalanx's dense formation tactics, where a good peripheral view was not required.

Usually, the helmet has a split in the mouth area, but in the Greek poleis of southern Italy (Apulia), solid helmets from the 6th to 5th centuries BCE are found. They resemble a kettle with openings for eyes and breathing in a characteristic T-shape, with the visor dividing the "T" in half. This type of helmet is called Apulo-Corinthian.

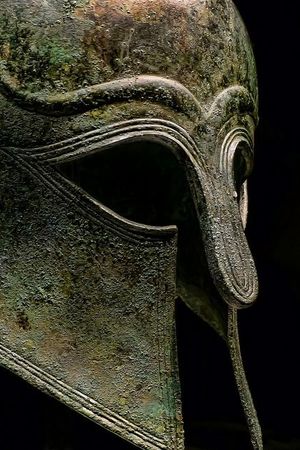

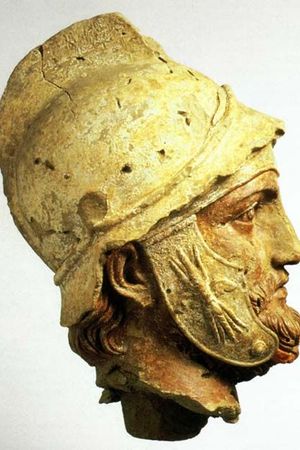

Corinthian helmet. Bronze, first quarter of the VI century BC, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities, Sully-sur-Loire.

Corinthian helmet. Bronze, first quarter of the VI century BC, Department of Greek, Etruscan and Roman Antiquities, Sully-sur-Loire.Chalcidian type

Chalcidian helmets emerged in the 6th century BCE and lasted for three centuries until they were displaced from mass usage by simpler pilos helmets and Thracian helmets in the 3rd century BCE. The visor of this helmet is either symbolic or absent, which improves visibility. Unlike the Corinthian helmet, the Chalcidian helmet features a distinctive cutout around the ears. This type of helmet is more comfortable but provides less protection to the wearer. The cheekpieces are wide and flat, with a rectangular or rounded shape, often with a wavy frontal edge. The cheekpieces can be fastened with loops. Visually, the helmet consists of two parts: the upper hemispherical dome and the lower section, connected at the prominently raised rim.

Attic type

Attic helmets are a variation of the Chalcidian helmet made by the craft school in Attica. Noted author Peter Connolly classifies the Attic type as a variant of the Chalcidian type, lacking a visor. Other differences from the Chalcidian helmet include pointed crescent-shaped cheekpieces usually fastened by hinges. The Chalcidian helmet was often adorned with a crest and feathers, while the Attic helmet featured an archaic Carian horsehair crest.

Boeotian type

The Boeotian helmet is an open cavalry helmet celebrated during the time of Alexander the Great. It likely originated in Boeotia in the 5th century BCE and later adopted in Thessaly. In terms of shape, it resembles an ancient Greek peasant hat with wide brims for sun protection. Ancient Greek author Xenophon recommended such a helmet for horsemen, along with a curved kopis-type sword. Macedonian hetairoi adopted it for their armament, and it was worn by rulers of Hellenistic states in Asia in the 3rd century BCE. It has wide brims that protect against downward sword strikes and cover the neck. It is comfortable for prolonged wear in hot climates and does not restrict visibility.

Phrygian type

The Phrygian helmet replicates the cap of Scythians, Thracians, and other Eastern peoples. The elongated dome curves forward. Warriors of the Macedonian phalanx fought in these helmets. Later, a metal crest began to be bent on the dome, and such helmets are called Thracian. In Macedonia, bronze Phrygian caps transformed into Thracian helmets by the 2nd century BCE, featuring an elongated upward dome and a simple, low metal crest or feather crest.

Thracian type

The Thracian helmet features an elongated upward dome. The visor is usually absent, and the flat cheekpieces have distinctive contours or are absent altogether. The Thracian helmet is also characterized by a metal crest placed on top of the dome.

By the 2nd century BCE, at the time of Roman conquest of Ancient Greece, the Thracian helmet became the most widespread in Greek armies. The crest became very low, but a visor appeared. The advantage of this helmet was its comfort, good visibility, and maneuverability, offering better protection than solid armor, especially against heavy swords and iron pikes. The helmet was named after the fact that during the Roman Empire, Thracian gladiators fought in it, covering their faces completely.

The transition to iron armor led to the abandonment of the universal Thracian helmets.

Pilos

The pilos is a helmet worn by lightly armed infantry. It was the main helmet of the Spartans during the Classical period, including the time of the Peloponnesian War. It is technologically advanced in its production. The pilos is a conical rounded bronze cap. The early examples in the late 2nd millennium BCE were made by assembling bronze scales. Solid metal pilos helmets emerged by the 5th century BCE. In the 3rd century BCE, pilos helmets were displaced in Greece by Attic helmets.

Related topics

Hoplite, Roman Army helmets, Celtic helmets, Gladiator helmets, Pileus, Gladiators

Literature

- Tsybulsky S. Voennoe delo u drevnevykh grekov [Military affairs among the ancient Greeks]. Ch. I Armament and composition of the Greek army. Warsaw, 1889.

- Frisk H. Griechisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, Band I. — Heidelberg: Carl Winter’s Universitätsbuchhandlung. - 1960. - p. 925-926. "Iliad", XXII, 314

- Heraklion Museum, Room 6, 1450-1300 BC

- Anthony Snodgrass, Archaic Greece: The Age of Experiment, University of California Press, 1981, p. 105, ISBN 0-520-04373-1

Gallery

Gallery