Recruitment in Ancient Roman Army

The army of ancient Rome has undergone a significant evolution from the times of the Roman Empire. Royal Rome before the late Empire era. Recruitment has always occurred among the male population, but the age and social status of those called up has changed. The recruitment system changed radically depending on political conditions, military needs, and social changes within the state.

Royal period (VIII-VI centuries BC)

In times of Royal Rome The army was a militia drawn from citizens in the event of war.

Picking principle service was the duty of all men capable of carrying arms.

Main military contingent: free citizens who owned land, since the warriors had to provide themselves with weapons.

Organization: the army was divided into " curiate legions "(according to the number of curia in Roman society).

Armament: fighters were armed according to their wealth (according to the principle "the richer, the better armed").

Early Republic (V-IV centuries BC)

After the expulsion of the kings (509 BC), the famous Servian reform (named after the king) was created. Servia Tullia), which laid the foundation for the legion system.

Pricing system: citizens were divided into 5 classes by income level, and their type of military service and weapons depended on this.

Militia army The army was formed as needed, after the war, the soldiers returned to their business.

Manipulative tactics: the army moved to a manipulative system, which made it more flexible.

Service life: usually 16 campaigns (but not in a row).

Middle and Late Republic (III-I centuries BC)

Rome expands its possessions, military campaigns become long and large-scale (for example, The Punic Wars). There is a need for a professional army.

Reforms of Marius (107 BC) resulted in the following changes:

Cancellation of the property qualification Questioner: now all citizens were accepted into the army, even the poor. Combined with the fact that military service is still considered a duty of every citizen, this gave the state an almost inexhaustible talent pool.

Professionalization: the army became permanent, with a 16-year service life. However, they usually spent 6 years in the army, and the rest were considered liable for military service, living a peaceful life at home.

In addition to the legions, many contingents of allies (socii) fought in the armies of Rome — vassal, dependent and allied cities and kingdoms of Italy, Spain, Greece, Macedonia, Africa, Asia Minor and so on. They usually had their own organization and commanders, but were provided with free food from the Roman treasury.

Government support: recruits received weapons, armor, and salaries, from which the cost of the above was deducted. Under Polybius (II century BC), a legionnaire received a stipendium of 120 denarii per year. Caesar raised it to 225, and the salary remained at this level until the end of the first century AD. However, unlike in the days of the principate, there were no systematic measures to reward veterans at the end of service.

Legionnaires ' loyalty: soldiers became more dependent on their commanders, from whose hands they received war loot and land when they retired, which led to an increase in the influence of warlords (example – Gaius Julius Caesar).

The procedure for assembling the army of the Republic in the second century BC is described by the Greek historian Polybius, who lived in Rome for many years and accompanied the military commander Scipio Aemilianus during the Third Punic War.

First, the draw determined the order in which soldiers would be recruited from the 35 tribes. After the annual election of consuls, 14 military tribunes were appointed. Each consul received two legions and 7 tribunes. Future legionnaires came to the tribunal in groups of four, and representatives of each of the four legions took turns choosing one. When the legions reached the required size, all legionaries took a solemn oath of obedience. Then the soldiers would go home and report for their legion's training camp on the appointed days. A funeral, illness, bad omen, sacrifice, or attack by a foreigner were considered valid reasons for not showing up. Centurions were chosen as privates and assigned their own options.

Principate (1st century BC-3rd century AD)

After the establishment of power Aug (27 BC) the army finally becomes professional and regular.

Contract service: soldiers signed a contract (usually for 20-25 years).

Set: mostly voluntary, but in case of shortage, forced conscription (dilectus) was used. Each person entering the service was tested for their physical qualities (probatio), age and height. If successful, he received the title of tiro or probatus, after which he was enlisted in one or another military unit. The fighter received a personalized lead plate (signaculum) and was henceforth considered a signatus, "marked". This was followed by a course of basic military training (4 months) and the swearing-in (sacramentum), usually on March 1.

Location: until the end of the second century AD, legions and auxiliaries were permanently stationed on the borders of the empire, rather than in Italy.

Auxiliary troops: contingents of allied peoples during the Republic of Venezuela auxilia - initially, the troops were mainly made up of Peregrines (subjects of Rome without the rights of Roman or Latin citizenship: Celts, Germans, Syrians, etc.), who were given Roman citizenship after serving.

Julius-Claudian period (27 BC — 68 AD)

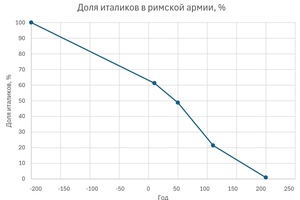

During this period, the Roman army, primarily the legions, still retained a strong Romano-Italian cultural character and ethnic composition. Under Octavian Augustus, the legions were recruited mainly from the urban population of Italy. However, even then there were exceptions to the rule: the legions of the Balkans and the East were replenished mainly from the number of local residents. There were few veteran colonies in these regions and, as a result, no Roman citizens at all. Therefore, if the recruits did not have Roman citizenship, they received it when enlisting in the army.

Difficulties in recruiting arose already at that time. Tacitus, through the mouth of the Emperor Tiberius, declared that only vagabonds and beggars would agree to serve in the army of their own free will. During the Great Illyrian Revolt and after the defeat of the legions of Varus in Teutoburg, Octavian was forced to resort to forced conscription in the still Republican manner (dilectus), and the ransom of slaves from the rich with the payment of half a year of their labor in order to enlist them in the army. According to Tacitus, the officials responsible for the draft released good recruits for bribes and recruited the maimed, weak and sick. In particular, and to reduce the amount of payments to veterans, Octavian in 6 raised the service period from 16 to 20 years in the legions and from 12 to 16 years in the Praetorian cohorts.

In 58 AD, the Roman general Domitius Corbulo was forced to demobilize many veterans of the III Gallica and VI Ferrata and organize an emergency conscription in order to replenish the number of these legions. However, the necessary number of recruits could not be recruited, and the core of the Corbulon expeditionary force was another legion and many auxiliary units.

However, during this period, about 61% of the legionnaires came from Italy, and the legions still retain their original cultural character.

Auxiliary units are in continuous development, turning from allied and vassal contingents recruited under different conditions into full-fledged regular units of the Roman army. Neither the length of service, nor the amount (or at least the availability) of salary, nor the granting of citizenship rights to veterans have yet taken established forms. So, the Germans from the Batavian tribe, famous for their military art, are exempt from any taxes and duties except for the need to supply recruits, and not only to the auxilia, but also to the elite bodyguard corps of the emperor. The XXII Deiotarian Legion was originally the army of the Galatian king, trained and armed in the Roman manner.

Moreover, cohorts of Roman citizens were already recorded during this period: cohortes ingeniorum civium Romanorum and cohortes voluntariorum civium Romanorum. Over time, there will only be more of them.

Flavian period (69-96)

In order to get as many recruits as possible, the Flavian emperors (Vespasian, Domitian, and Titus) consistently pursued a policy of urbanizing and romanizing the citizens of newly created cities. They created special colleges of youth, whose main duty was to send recruits to the legions.

The recruitment of Italians to the legions is sharply reduced. So, if under Nero the majority of the fighters of the XV Apollonian Legion were Italians, then under Flavius and later — only a small part. From now on, the Italians have the advantage of the Praetorian cohorts, the legions are mostly replenished by provincials from the cities of the most romanized provinces. The Roman army began to lose its Romano-Italian cultural character, gradually turning into a truly imperial army. However, the vast majority of centurions in this period still come from Italy or the old veteran colonies in southern Gaul, Spain, and Macedonia. Many centurions spend part of their service in Praetorian or urban cohorts, helping to maintain a certain cultural unity of the diverse army. Emperor Domitian raised the salary from 225 to 300 denarii a year, in an effort to fend off the loss of purchasing power of the salary due to inflation. Under him, the law still prohibits slaves from serving in the military.

The Antonine period (96-192)

By the reign of Emperor Trajan, the proportion of Italians in the army drops to 21.4%. He decides to improve the situation and introduces alimenta-state loans to wealthy Italians to raise free-born children from poor families. According to the plan, these children were supposed to make up the army's personnel reserve. However, this measure did not bring the desired result, and by the end of the second century the share of Italians in the army falls to 0.9%. Trajan also recruits a lot of auxiliary units, especially equestrian and mixed. Some of them, such as horse archers and cataphracts from the Alans and Sarmatians, receive Roman citizenship either immediately at the foundation or shortly after. The value of these branches of the armed forces, apparently, determined the special privileges of new units, and they could only be recruited from local natives who were little or no Romanized. The proportion of soldiers ' sons from unofficial wives living in villages surrounding military camps, and in the case of eastern troops — directly in the cities of permanent deployment of military units, is steadily increasing. Tombstones of such soldiers at the place of birth bear the mark ex castrensis, "from the camp". By the end of the second century, the place of origin of a soldier ceases to be indicated at all.

Emperor Hadrian is reforming the recruitment system. Each legion now receives a fixed recruitment zone. For example, the Rhenish legions received both Germanies, Raetia, and the three Gallic provinces (tres Galliae). This also affected the auxiliary units, and from this point on, the proportion of recruits granted citizenship upon joining the legion, as well as the proportion of citizens in the auxilia, only grow. Even before this reform, in 113-117, a Roman citizen, Marcus Rutilius Lupus, asked the prefect of Egypt to enroll him in the auxilia (ChLA, XLII, 1212). The bulk of recruits are now supplied by military camps, military quarters of cities where army units are permanently stationed, and rural areas. Already under Hadrian, the provinces were beginning to complain about the burden of conscription. According to some sources, the legions were still able to receive reinforcements from the fleet. For example, we know the petition of 22 Egyptians from Legio X Fretensis during the reign of the Emperor Antoninus Pius, the legate of Syria, Willius Cad, asked to confirm their status as veterans of the legion, that is, obtaining Roman citizenship and other benefits. The fact is that these soldiers began their service in the navy, where they took even freedmen, and most likely did not have Roman citizenship. Their petition was granted.

Under Marcus Aurelius, the army succumbs first to the Antonine plague, and then to some twenty years of brutal Marcomanian wars. The army suffers huge losses, and to replenish them, the Italians are conscripted, volunteer slaves, gladiators, freedmen and mountain bandits from the Dardani and Dalmatian tribes are taken into service. Moreover, from the defeated and allied barbarians, Rome constantly requires thousands of young men to replenish the losses in the army. According to papyri from Egypt in the 160s, an edict is being issued granting Roman citizenship rights to all sons of Roman soldiers, regardless of their status or whether they are married, so much so that the government needs Roman citizens, from whom it tries first of all to recruit legionnaires.

As for the auxilia, in the year 144 the children of its veterans no longer receive Roman citizenship. This is explained either by the desire to encourage the sons of veterans to follow in the footsteps of their fathers, or by the dominance of Roman citizens in auxilia, which made the privilege of granting citizenship to their children redundant. From the reign of Hadrian until the 170s, the ratio of citizens to Peregrines in the auxilia is almost equal, and after that the citizens begin to form the majority. The Peregrines now serve an advantage in irregular ethnic units called, according to various historians, numeri or nationes. These units initially had their own structure, weapons and tactics, and instead of receiving military allowances (stipendium), they received monetary payments (salarium).

Reign of the Northern Dynasty (193-235)

After coming to power as a result of his victory in the civil war, Emperor Septimius Severus declared himself the heir to Pertinax and the avenger of his murder. The Praetorians responsible for Pertinax's death and defeated by Severus ' forces were disbanded in disgrace, and Severus recruited new Praetorian cohorts from the best soldiers of his legions, mostly Illyricans by origin. Thus the Praetorian Guard lost its Romano-Italian character, just as the army had lost it before. At the same time, and partly as a result of this, the proportion of Italians in the centurions decreases during the reign of this dynasty. The officer corps, the backbone of the Roman army, is also changing from Romano-Italian to imperial, cosmopolitan and diverse.

Severus recruits three new legions, I, II and III Parthians, and II Parthians receives a permanent camp in Italy, for the first time in Roman history, in the Alban Hills near Rome. Also revived is the Pretentura Italiana and the Alps, a group of troops for the defense of northern Italy that was temporarily formed during the Marcomanian Wars and then disbanded. In addition to the II Parthian in Italy, there are now permanent vexillations of legions and auxiliary units.

The North gives all centurions access to the equestrian class. Competent and successful centurions begin to occupy equestrian military positions, such as commanding new legions (instead of senatorial legates), auxiliaries, and vexillations. Given the steady decline in the proportion of senior and senior officers from the senate estate, this leads to the provincialization of the highest command staff of the army. From now on, the highest positions in regional groups of troops are occupied mainly by local aristocrats and successful nominees from the ranks, also of local origin, who have the closest ties with the local elites, and almost none with the capital.

His son Caracalla, guided, according to various historians, by the desire to increase the collection of taxes, increase the number of recruits to the legions and other considerations, in 212, grants Roman citizenship to all free inhabitants of the empire, erasing the remnants of differences in civil status between the soldiers of the legions and auxiliaries. The process, which has been going on since the time of Octavian, gets its formal completion. The number of irregular units (numeri or nationes) recruited from soldiers outside the empire increases.

The North also allows soldiers to cohabit with their wives in cities and towns near military camps. More and more recruits come from the sons of veterans and soldiers still in service. He again raises the salary of soldiers and introduces free distribution of food to soldiers on campaigns (before that, the cost of food was deducted from the salary).

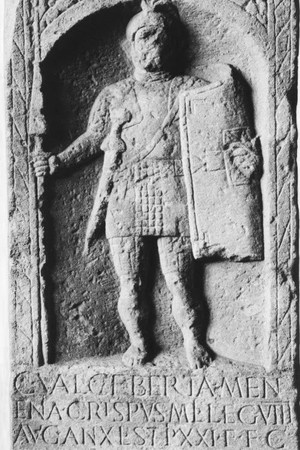

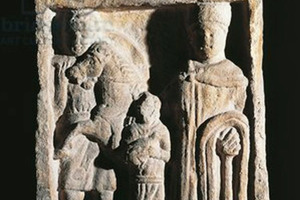

Tombstone of legionnaire Lucius Septimius Viator from II Parthica, AD 218

Tombstone of legionnaire Lucius Septimius Viator from II Parthica, AD 218

Period of the reign of the soldier emperors (235-284)

This period did not go down in history as a crisis of the third century for nothing. Rome waged continuous wars with the migrations of the Great Migration peoples along the Rhine and Danube, with the Persians-Sasanians in the east, not counting the mass of civil wars of various claimants to the imperial purple, supported by different regional groups of troops. Not much is known about military recruitment during this period. The number of nationes increases, and foederati appear-contingents of peoples allied to Rome, often settled on deserted lands in exchange for payment of taxes and the supply of recruits to the troops. According to ancient tradition, any veteran of Roman regular units received citizenship if he did not have it before, and his son could already serve in any part of the army, exacerbating its ethnic and cultural heterogeneity.

In the middle of the third century, under the Emperor Gallienus, the senatorial origin of a senior or senior officer becomes an exception, as a rule, at all levels of the vertical command, from centurions to prefects of legions, there are people from the equestrian class: either successful nominees from the lower ranks, or provincial aristocrats.

At the same time, the phenomenon of Illyrian soldiers and officers who were imbued with the Roman spirit and considered themselves heirs of the glory and culture of the heroes of the Republic's times is clearly manifested. The reign of a succession of emperors from Claudius II to Diocletian is called the "Illyrian junta"by many historians. It was these warriors and commanders who managed to restore order in the country, carry out the necessary reforms and defeat the enemies in all directions.

Dominat (since 284)

Rome at the end of the III - beginning of the IV century needed a much larger army more than in the old days, and the principle of voluntary service could not physically meet the needs of the military machine. The population declined significantly due to the Antonine plague, the Cyprian Plague, and a series of civil wars, and with it the number of volunteers willing to serve in the army decreased. In addition, a series of defeats suffered by the Romans in the third century AD, combined with a drop in the purchasing power of soldiers ' salaries, made military service not very attractive in the eyes of the population. Therefore, the appeal came to the fore. Landowners were required to supply the army with a certain number of recruits, in proportion to the size and wealth of their land. In addition, since the time of Emperor Constantine, the sons of military men were also considered liable for military service, which made military service hereditary and served as a serviceable source of recruits (according to some sources, the sons of veterans made up the vast majority of recruits). And here the regional differences of a huge and heterogeneous empire affected. In more peaceful and economically developed provinces, such as Italy, recruits were often marginalized peasants or just vagabonds, whom landowners tried to put in place of their own peasants. But recruits from Gaul and Pannonia were famous for their high qualities until the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Barbarians resettled to cultivate the lands of the empire that were devastated during the third century were also called up. Barbarians from outside the empire could also serve in the army, but their percentage became significant only in the V century. As a result, the average level of recruits could be very, very different.

Briefly about his service in the Roman Navy

As for the navy, even freedmen were recruited into it, and most of the experienced sailors and officers were natives of the Hellenistic East, in particular, Egypt. The Greeks from Alexandria were especially appreciated. If only citizens of the Hellenistic poleis of this province could serve in the auxilia, then all local natives were taken to the fleet. Each warship had up to a century of heavy infantry under the command of a centurion, and there were cases when these infantry were transferred to land units, up to the formation of entire legions. They served in the Navy for up to 25 years. At the end of the service, the sailor received a "diploma" along with other stateless military personnel. The ceremony of receiving this diploma was very important for the sailor. It was after this ceremony that he became a veteran and left the service. However, the service was very difficult even in peacetime: diseases and epidemics on ships, storms and shipwrecks. Therefore, not everyone lived to the end of the service. In addition, it is quite common for seafarers to be decommissioned earlier without receiving their diploma: "An extremely large number of seafarers who have served for 25 years were probably given missio causaria (sick leave) at this stage, so that they could not receive their diplomas." (Bannikov, Morozov. "History of the Roman and Byzantine Navy", p. 101). Sailors who received a diploma became full-fledged Roman citizens. They received the right to enter into a legal marriage, as well as to transfer citizenship to their children born in this marriage.

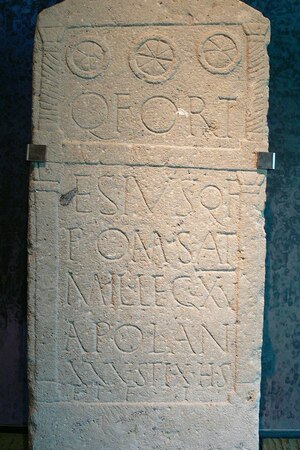

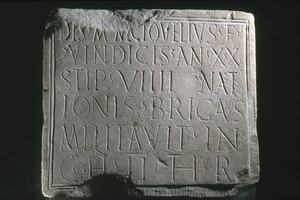

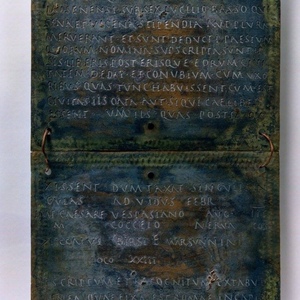

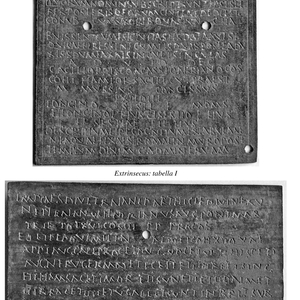

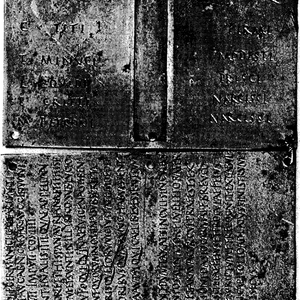

Military Diplomas

Military diplomas (diploma militaria) are official bronze documents issued to soldiers of the auxiliary forces (auxilia) and the navy (classis) after completion of service. They confirmed the receipt of Roman citizenship and other privileges. The military diploma consisted of two bronze plates sealed with seals. On the outside, the emperor's decree granting the right to citizenship was indicated. On the inside – the name of the veteran, his military unit, place of service and a list of witnesses. A military diploma granted such privileges as Roman citizenship, the right to marry legally, and access to civil rights (for example, the ability to serve in the municipal administration, conduct official business in court).

Military diplomas were awarded:

- Veterans of auxiliary troops (auxiliaries) – peregrines who served in the cavalry (alae) or infantry units (cohortes).

- For seafarers roman fleet.

- In some cases, soldiers of the Praetorian and city cohorts.

Legionnaires did not receive diplomas.

Granting citizenship to veterans was a powerful tool for romanizing provinces. They turned former barbarians into full-fledged Romans, making them loyal citizens of the empire. Diplomas were used from about the first century AD (the time of Claudius) until the third century, when citizenship became widespread (the Edict of Caracalla, 212 AD). Today, many military diplomas have been found by archaeologists – this is the most important source for the military history of Rome.

Conclusion

The Roman army began as a classical polis militia, but by actively establishing colonies and granting citizenship rights to the subordinate cities and communities of Italy, Rome was able to recruit a significant army capable of conquering almost the entire Mediterranean. Naturally, at every step of this path, the Romans were helped by allies and satellites, first the Italians, and then the Gauls, Spaniards, Numidians, and many others.

When Rome's power extended over the entire Mediterranean, it naturally shared the burden of military service with the conquered peoples. Its most worthy representatives, like the Italians, once received Roman citizenship and served in its legions and auxilia. The practice of using the troops of allies and dependent peoples also did not go away, they served in the units of nationes and federates.

The empire became increasingly diverse and cosmopolitan, and at some point the Romano-Italian component of its culture and army became not the leading one, but only one of many others, for example, Romano-Illyrian and Romano-Gallic. Over time, not only the rank and file, but also the officer corps, including its top, became provincialized. Ideologically, the army was united by a developed culture that grew out of the Romano-Italian values and traditions of the Republic. The Roman military was proud of its status as the elite of the world's greatest power, proud of the glorious military path of its military unit and its traditions.

Another remarkable achievement of Rome was the professional standing army. Military service on the support of the state as such was nothing new, but only the Romans were able to implement it on an unprecedented grand scale over a long historical period. At the same time, hundreds of thousands of military personnel were fully supported by the state for centuries, received regular military training and were subject to discipline. Moreover, Rome was eventually able to establish a system of training competent officers with combat experience at all levels, including the high command. This is a striking difference between the Roman army and any previous or modern one, where the highest command posts were somehow inherited from the hereditary elites of society by birthright. In Rome, since the third century, intelligent soldiers have worked their way up from ordinary soldiers to commanders of legions, and sometimes even emperors.

List of literature

The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume X, The Augustan Empire, 43 B.C. — A.D. 69. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XI, The High Empire, A.D. 70-192. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume XII, The Crisis of Empire, A.D. 193-337. Cambridge University Press, 2008.

Gladius. The World of Roman Soldier. Guy de la Bédoyére. The University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Evolution of the Roman military system I-III centuries Bannikov A.V., St. Petersburg: EVRAZIYA Publ., 2013.

The Roman Army in the IV century. From Constantine to Theodosius. Bannikov A.V.

WERNER ECK – PAUL HOLDER – ANDREAS PANGERL. A DIPLOMA FOR THE ARMY OF BRITAIN IN 132 AND HADRIAN’S RETURN TO ROME FROM THE EAST. aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 174 (2010) 189–200 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn

Roman Military Tombstones. Alastair Scott. Shire Publications, 1984

Related topics

Legion, Auxilia, Ancient Roman Navy, Royal Rome, Roman Republic, The Roman Empire, Military campaigns of the Roman Republic, Late Roman Army